Feature

Tailor-Made for Evil

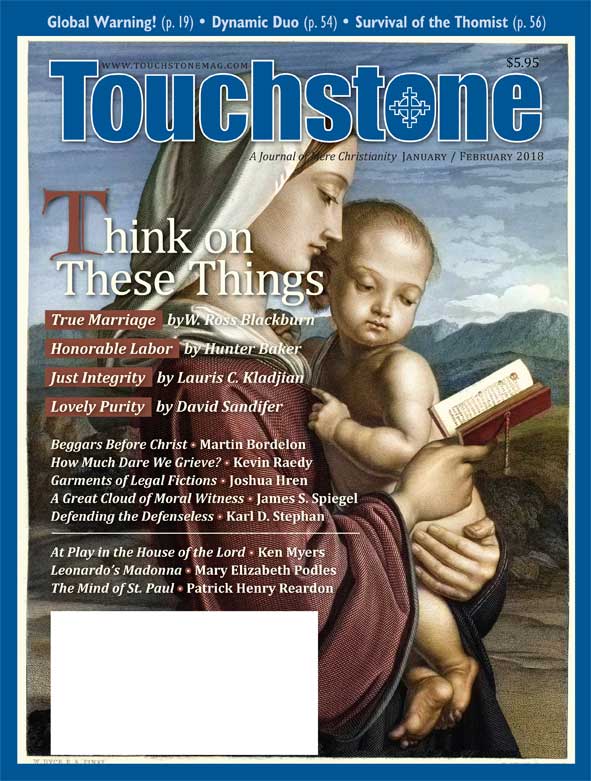

Hiding Foul Things with Garments of Legal Fictions by Joshua Hren

Gustave Doré's drawing of Dante's illicit lovers Paolo and Francesca presents us with an eternal inversion of their earthbound, extramarital Eros. For though the two lovers are enclosed in sheets, their infernal consummation is not cloaked: we see the nakedness of their affair, rather than the covers which could lend modesty to their misdeeds. In The Revenge of Conscience, J. Budziszewski notes that "because we can't not know that sex belongs with marriage, when we separate them we cover our guilty knowledge with rationalizations."

Doré's sheets give guilty rationalization physical form, even if they fail to conceal the lovers. At times, though, such rationalizations are threaded through less tangible things. Although, in the words of Aquinas, law ought to be a "dictate of reason" concerning "what should be done to insure the common good," legality can also be a garment by which we try to cover our guilt.

Paolo and Francesca inhabit Canto Five of Dante's Inferno, where the souls of the damned are swept by storm and counterstorm, whirled about in an eternal, restless flight. Of this black wind Dorothy L. Sayers writes: "As the lovers drifted into self-indulgence and were carried away by their passions, so now they drift forever." Their punishment is the sin itself, seen without illusion, "seen as it is—a howling darkness of helpless discomfort." Here we meet the carnal, those who betrayed reason to gratify appetite, sinning in the flesh.

The first among this number is Semiramis, the legendary Queen of Assyria, who was so corrupted by mad sensuality "that to hide the guilt of her debauchery / she licensed all depravity alike, / and lust and law were one in her -decree." Dante draws his knowledge of Semiramis from the Christian historian Orosius, who in his Historia adversus Paganos documents how lust and a thirst for blood were intertwined in Semiramis; those she summoned to her by royal command and held in her adulterous embrace she also murdered. Orosius tells us that

She finally most shamelessly conceived a son, godlessly abandoned the child, later had incestuous relations with him, and then covered her private disgrace by a public crime. For she prescribed that between parents and children no reverence for nature in the conjugal act was to be observed, but that each should be free to do as he pleased.

Semiramis did not alter the laws only for the purpose of increasing occasions wherein she might sate her lust. "She licensed all depravity," Dante writes, in order to "hide the guilt of her debauchery." In other words, she felt shame, a shame so strong that she rewrote the laws in order to at least gain legal sanction for her disordered acts. The phenomenon of Semiramis raises poignant questions about the relationship between promulgated laws and the objective order. For Semiramis is alive and well today, and if only a few have noticed her, it is probably because the empress has new clothes.

Morality Untouchable by Law

Under the regime of liberal individualism, we have tried to cut the Gordian knot of the seemingly intractable tensions between conscience and legality, between natural law and positive law, by avoiding the language of guilt and debauchery entirely and instead conducting a vivisection of the good. These days, the good is whatever a person freely decides is good. But as law professor Robert T. Miller has noted, "this amounts to saying that whatever conclusions a person reaches on these most important issues will of necessity be correct, at least for that person: a conclusion will be the correct one precisely because it was the conclusion that the person reached" ("Achilleus Now," 2003).

This account of the good, of course, entirely avoids the question of how one who does not yet know what is good should go about trying to learn it. But it satisfies the logic of liberal individualism. While Semiramis needed to alter the laws forbidding adultery and incest in order to gain public sanction for her lust, we make individual liberty the law of all, and thereby—to put it in Dante's poetic register—

Denying even the word "debauchery"

We swear that liberty's a mystery—

Morality's untouchable by law.

Share this article with non-subscribers:

https://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=31-01-034-f&readcode=5449

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on literature from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor