Feature

Tailor-Made for Evil

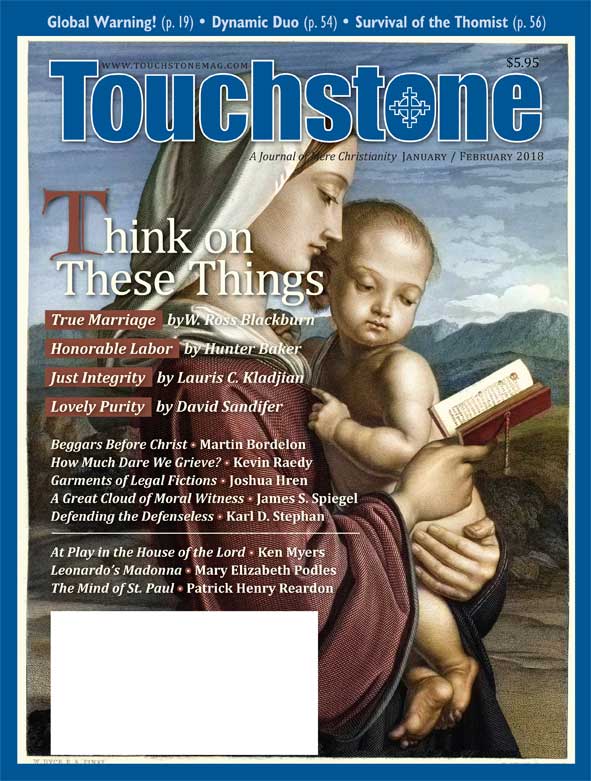

Hiding Foul Things with Garments of Legal Fictions by Joshua Hren

Gustave Doré's drawing of Dante's illicit lovers Paolo and Francesca presents us with an eternal inversion of their earthbound, extramarital Eros. For though the two lovers are enclosed in sheets, their infernal consummation is not cloaked: we see the nakedness of their affair, rather than the covers which could lend modesty to their misdeeds. In The Revenge of Conscience, J. Budziszewski notes that "because we can't not know that sex belongs with marriage, when we separate them we cover our guilty knowledge with rationalizations."

Doré's sheets give guilty rationalization physical form, even if they fail to conceal the lovers. At times, though, such rationalizations are threaded through less tangible things. Although, in the words of Aquinas, law ought to be a "dictate of reason" concerning "what should be done to insure the common good," legality can also be a garment by which we try to cover our guilt.

Paolo and Francesca inhabit Canto Five of Dante's Inferno, where the souls of the damned are swept by storm and counterstorm, whirled about in an eternal, restless flight. Of this black wind Dorothy L. Sayers writes: "As the lovers drifted into self-indulgence and were carried away by their passions, so now they drift forever." Their punishment is the sin itself, seen without illusion, "seen as it is—a howling darkness of helpless discomfort." Here we meet the carnal, those who betrayed reason to gratify appetite, sinning in the flesh.

The first among this number is Semiramis, the legendary Queen of Assyria, who was so corrupted by mad sensuality "that to hide the guilt of her debauchery / she licensed all depravity alike, / and lust and law were one in her -decree." Dante draws his knowledge of Semiramis from the Christian historian Orosius, who in his Historia adversus Paganos documents how lust and a thirst for blood were intertwined in Semiramis; those she summoned to her by royal command and held in her adulterous embrace she also murdered. Orosius tells us that

She finally most shamelessly conceived a son, godlessly abandoned the child, later had incestuous relations with him, and then covered her private disgrace by a public crime. For she prescribed that between parents and children no reverence for nature in the conjugal act was to be observed, but that each should be free to do as he pleased.

Semiramis did not alter the laws only for the purpose of increasing occasions wherein she might sate her lust. "She licensed all depravity," Dante writes, in order to "hide the guilt of her debauchery." In other words, she felt shame, a shame so strong that she rewrote the laws in order to at least gain legal sanction for her disordered acts. The phenomenon of Semiramis raises poignant questions about the relationship between promulgated laws and the objective order. For Semiramis is alive and well today, and if only a few have noticed her, it is probably because the empress has new clothes.

Morality Untouchable by Law

Under the regime of liberal individualism, we have tried to cut the Gordian knot of the seemingly intractable tensions between conscience and legality, between natural law and positive law, by avoiding the language of guilt and debauchery entirely and instead conducting a vivisection of the good. These days, the good is whatever a person freely decides is good. But as law professor Robert T. Miller has noted, "this amounts to saying that whatever conclusions a person reaches on these most important issues will of necessity be correct, at least for that person: a conclusion will be the correct one precisely because it was the conclusion that the person reached" ("Achilleus Now," 2003).

This account of the good, of course, entirely avoids the question of how one who does not yet know what is good should go about trying to learn it. But it satisfies the logic of liberal individualism. While Semiramis needed to alter the laws forbidding adultery and incest in order to gain public sanction for her lust, we make individual liberty the law of all, and thereby—to put it in Dante's poetic register—

Denying even the word "debauchery"

We swear that liberty's a mystery—

Morality's untouchable by law.

This is what Justices O'Connor, Kennedy, and Souter, channeling the individualist cosmos, stated in their opinion concerning Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992): "At the heart of liberty is the right to define one's own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life. Beliefs about these matters could not define the attributes of personhood were they formed under the compulsion of the State." In other words, whereas Semiramis sought refuge in the state, using law to give her lust respectability, the Justices employed the judicial branch of the state to deconstruct law itself, using law to forbid laws on matters of human life and personhood. As Justice Scalia said in response to this opinion, "I have never heard of a law that attempted to restrict one's 'right to define' certain concepts; and if the passage calls into question the government's power to regulate actions based on one's self-defined 'concept of existence, etc.,' it is the passage that ate the rule of law."

In terms of our exploration of the relationship between guilt, shame, and law, we might say that those who opine along the lines of the aforementioned Justices wish to make a world wherein no one feels shame except on terms they themselves determine. In such a world, one would not need to alter the laws to hide one's sin, because there would be no sin, only "concepts."

Altering Nature by Law

The above passage pertains to abortion, but we can also find this same garment of legality clothing a more recent composition of the nation's highest court—one that merits close study as it is a paradigm of the Empress's New Clothes:

The history of marriage is one of both continuity and change. Changes, such as the decline of arranged marriages and the abandonment of the law of coverture, have worked deep transformations in the structure of marriage, affecting aspects of marriage once viewed as essential. These new insights have strengthened, not weakened, the institution. Changed understandings of marriage are characteristic of a Nation where new dimensions of freedom become apparent to new generations. (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015)

Here, the empress strives to employ history as an authority. Historical changes, so the argument goes, necessitate legal changes. History is more authoritative than nature itself. It is important to note, however, that in this case, "sociological realities," such as the decline of arranged marriages, have altered marriage, and that therefore the very nature of marriage has changed.

If we are prompted to ask how it is possible that inclusion of homosexual partnerships in the definition of marriage could strengthen, rather than weaken, the institution, Obergefell seems to have anticipated our objection by offering a new description (definition?) of the very nature of marriage: "The nature of marriage is that, through its enduring bond, two persons together can find other freedoms, such as expression, intimacy, and spirituality." If we read this line carefully, we come to see that marriage itself is an institution that serves freedom.

Of course, though it dramatically corrupts the natural law, Obergefell nonetheless relies on the language of "nature" to set forth the new meaning of marriage. Semiramis has new clothes. Whereas the ancient Semiramis sought to assuage her conscience simply by making her aberrant acts legal, the new Semiramis, as she slouches toward Washington to be born, strives to alter nature itself by means of the law. In so doing, the garment of legality offers not merely a new outfit, but a new body.

Freedom Made Compulsory

Semiramis's metamorphosis of nature does not stop with the nature of marriage, however. As I noted, marriage is now made for freedom, and yet the shift in the definition of marriage requires that freedom itself also undergo an operation:

Rights implicit in liberty and rights secured by equal protection may rest on different precepts and are not always coextensive, yet in some instances each may be instructive as to the meaning and reach of the other. In any particular case one Clause may be thought to capture the essence of the right in a more accurate and comprehensive way, even as the two Clauses may converge in the identification and definition of the right. This interrelation of the two principles furthers our understanding of what freedom is and must become.

In his dissenting opinion concerning the Obergefell decision, Justice Clarence Thomas continued Scalia's critique of the character of the opinion in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, noting that it veered from the traditional view of the Court, which understood liberty "as individual freedom from governmental action, not as a right to a particular governmental entitlement," such as, for instance, a marriage license. But now, freedom is presented as an endless mystery, and, as Scalia put it, this understanding of liberty morphs law into "the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie."

Importantly, though, whereas the Court's opinion on abortion sought to deliver the individual from the "compulsion of the State," in Obergefell,the fundamental right to marry was made compulsory by that same state. Mystical in character, it has been made into a Law. And whatever other benefits the proponents and celebrants of Obergefell might reap, the paramount one is the quelling of natural guilt and the sense of shame by a promulgated law that participates in the attempt to master and remake nature.

Still, the fact that so much effort had to be put into securing public sanction of same-sex marriage implies that a world without shame, which should result from a "right to define one's own concept of existence," has not yet arrived in full. Curiously, while deep shamelessness might mean that fewer people will strive to make depravities legal, the persistence of shame and guilt may, in our individualist regime, result in more cases like Casey and Obergefell.

The Slavery of Modern Freedom

For their punishment, the carnal are forever deprived of the light of reason. Although emotivism may be the spirit of our times, we are yet not wholly deprived of reason's light and of the truths it makes clear concerning our moment—particularly with respect to the metamorphoses of liberty, legality, and—so the argument goes—nature itself. We cannot swoon with Dantean shock, then, when we open our morning papers to read of Semiramis v. The State, wherein a mother seeks legal sanction for her incestuous relationship with her son.

This is not rhetorical hyperbole. Anyone acquainted with the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns will be able to read such a newspaper headline in the fortune cookie of modern freedom. Leo Strauss wrote that "only in the light of the quarrel between the ancients and the moderns can modernity be understood." Aristotle knew that many democracies fail because those who rule "define freedom badly" (Politics 1310a 26). This is because freedom defined as doing whatever one desires is not freedom, but slavery—and slavery to a harsh master. And there is nothing intrinsic to modern freedom that prevents us from defining it as doing whatever one desires.

An ancient may be able to help us see that what moderns have come to call liberty is actually slavery. But modern liberty did not define itself by a quarrel with the ancients only. It was born in pangs of reaction against the Christian vision. As Pierre Manent wrote in A World Beyond Politics? (2006), "to counter the corrupting effects of a religion that imposed its truth, the question of liberty was separated as completely as possible from the question of truth. That meant that human beings were defined by liberty or that truth was declared to reside in liberty." Of course, as the modern Semiramis reveals, this liberty does not end in mere autonomy. Rather, the garment of legality demonstrates modern freedom's demand that others recognize and respect the modern's declaration of self.

But no matter how carefully wrought their garments, those who have eyes to see must state our situation clearly. It is not merely that the empress has no clothes. It is not merely that the empress has new clothes. Unable to shake that stirring of human consciousness which demands what Hegel called recognition, and in order to quiet that human conscience which tells her she cannot in fact change nature, the newly clothedSemiramis insists that she also has a new body.

Reason Insufficient

It is at this point that we see again the qualified truth of Shelley's claim that poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world. Whereas Shelley was referring to writers of verse, I mean that our legislators themselves must have the aspirations of Ovid, aspirations evidenced in their efforts to cause the metamorphosis of the very nature of marriage and of liberty. Heidegger is not entirely wrong when he states that man dwells poetically on the earth. But man also dwells politically. Our examination of the empress's new clothes should reveal that, harsh as his judgments seem, Plato's banishment of the poets was rooted in wisdom. In the Obergefell decision, we see what happens when poetic fictions permeate the legislative body of our republic.

And yet, like Socrates, we cannot help but find in the poets passages of greatness, passages that capture poetry's power to delude. In the Purgatorio, in the cornice of the slothful, Dante dreams of a Christianized Siren. When he sees the Siren, Dante "stared at her; and just as the new sun / breathes life to night-chilled limbs, just so my look / began to free her tongue, and one by one / drew straight all her deformities, and warmed / her dead face, till it bloomed as love would wish it / for its delight. When she was thus transformed," she began to sing, indicating that she "turned Ulysses from his wanderer's way" with her "charmed song."

Here Dante gives poetic form to legal fictions that strive to remake nature. For the Siren is naturally hideous, and although in his mind he makes her beautiful, she yet remains rancid by nature. Still, the dreamer is deluded. He takes the artifice for the natural truth.

Natural reason cannot alone deliver Dante from such a dire delusion. Nor can it deliver us from ours. Although it is true that the ancients possessed clarifying truths by which we can see the actual character of modernity, the quarrel is not merely between the ancients and the moderns. The Christians, too, have something to say.

In The Divine Comedy, although reason is given its just due, the human capacity for poetic delusion is, too. The poem makes clear that only a "saintly lady" can rouse Dante from the dreamy metamorphosis by which he transforms incontinence into a beauty that delights. It is true that the saintly lady does so by rousing Virgil, the natural virtue of antiquity, that recte ratio which is able to rip away the beguiling garment and expose the awful stench that effuses from the core of the lovely Siren. But right reason is roused by grace, a grace that we need, too, if by reason we are to lay bare the foul things, cloaked by the garment of legality, by which our body politic is governed.

Share this article with non-subscribers:

https://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=31-01-034-f&readcode=5449

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on literature from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor