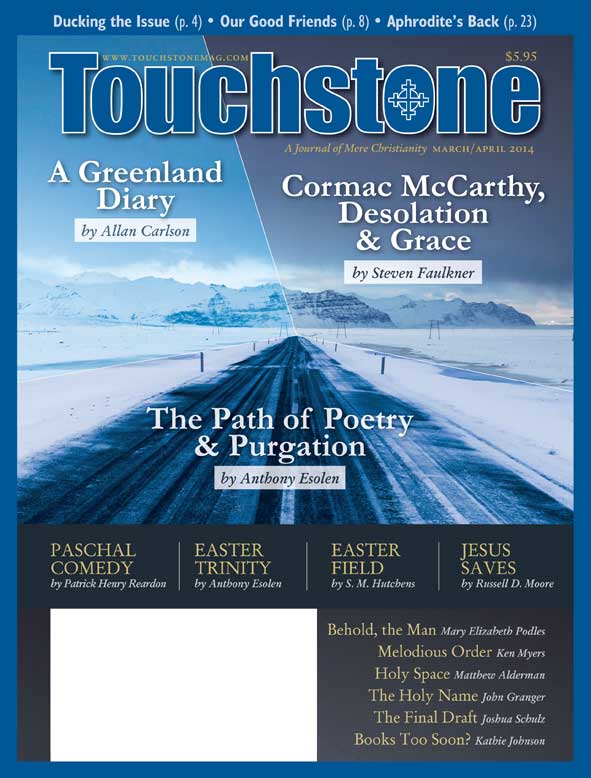

Feature

Poetry Above Compulsion

Higher Education Should Advance the Glorious Liberty of the Sons of God

by Anthony Esolen

In the dim years of the sixth century, when the half-barbarian Germans had perforated the Roman Empire in the west, St. Benedict drew up his Rule, a counteroffensive, a plan for battle. I am not claiming that he understood it as such, in any political sense. But in the midst of that crumbling civilization, he sheltered in his citadel what civilization is ultimately for: the freedom of the human spirit to contemplate the everlasting things, and to share with others the fruits of that contemplation.

If we consider it in that light, it was no accident at all, but the foreseeable consequence of the work of Christian prayer, that his monks would preserve and hand on to future generations the great expressions of human freedom made manifest in the poetry and philosophy of the pagan world. It was not the first time, and it would not be the last, that, in her devotion to God, a devotion made possible by the grace that at once satisfies all that is human in us and raises us beyond ourselves, the Christian Church should do for man what he could not do for himself.

What did the world understand then, if not conquest? What does it understand now? Our barbarians do not scale our city walls with fire and sword. Their weapons are more impressive than that. Now all the massed ordnance of technology and advertising and broadcasting, all the manifold lies told by economic and political determinists, all the self-compelled ambitions of scientists whose livelihoods depend on homage to the daemon demanding, "Farther, more"—all of those engines of compulsion are aimed against the very being of man, to set him free from his humanity, free to sink back into the blamelessness of the beast, or into the inert apathy of a mere object, not above the moral law, but beneath it.

Man Needs the Heavens

The Church alone remains, proclaiming that all created things find their end only in the beatitude of man, because, as St. Paul mysteriously says, "the creature itself also shall be delivered from the bondage of corruption into the glorious liberty of the children of God" (Rom. 8:21). The Church is for the world, because she is for man; the Church is for man, because she is for God.

That is why we now see that almost the only schools where reverence for humanistic letters is to be found are also places of prayer. This is not because their professors have grown stubborn and antiquarian. It is again the foreseeable consequence of following Christ in a dark age. The air is cleaner in the citadel at the mountaintop, and they who still yearn for it can drag themselves out of the current of the times, fight through the thickets, and climb that mountain, to breathe freely as men, to see, and to wonder.

That is what our Christian colleges and schools should be about. It is the principle that underlies Cardinal Newman's work, The Idea of a University. Newman does not deny that we need tradesmen—we need merchants, and carpenters, and scientists engaged in applied research, and plumbers. But, if I may be allowed the play on words, we need most what we do not need at all. Grant a man a hundred years of health, good food, sexual release, and what passes for important work; grant him that on condition that he remain in a well-decorated basement, with a ceiling fixed over his head, and a painted heaven dotted with painted stars in his room at night, and he will go mad. He needs more than to see. He needs to behold. He needs the heavens.

A Work of Love & Joy

Let me begin to illustrate the point by bringing to your attention a couple of works of art both human and sacred. Recently, my family and I visited New Bedford, once a jewel of a town, with cobblestone streets and colonial houses built by the men who went down to the sea in ships, to hunt the great whales and bring back the whale-ivory and oil and spermaceti. Those ventures engaged maritime peoples from all over the world, including the Portuguese, from Portugal and the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands, many of whose descendants still live in New Bedford and the area around it. The museum in New Bedford is filled with their works of art—folk art, as we would call it. The whalers were not exceptionally learned men. One object impressed me most by its extraordinary delicacy and beauty.

It is a sculptured altarpiece from Cape Verde, gleaming white. The altar is festooned with a riot of flowers, whose petals are rendered with the most exact care. A large monstrance is carved upon the altar, with rays radiating from the center, where stand the letters I H S, the Greek capitals for the first three letters of the name of Jesus. Above the flowers stands the figure of the Lamb from the Book of Revelation, holding his banner with the cruciform insignia. An unfurled semicircle of diamonds provides a canopy for the altar, each diamond bearing a letter, reading HOC EST ENIM CORPUS MEUM, "for this is my Body," the words of Christ at the Last Supper.

To the left of the altar, at a dramatic angle, stands the Cross; to the right, at a corresponding angle, the anchor of hope, dear to the hearts of sailors. That's all that the modern tourist would understand of it; of course a maritime people would value the utility of an anchor. But the sculptor knows better. He is thinking of the promise made by God to Abraham and confirmed with an oath, a promise extended to all of Abraham's spiritual sons and daughters, "which hope we have as an anchor of the soul," says the writer to the Hebrews, "both sure and steadfast, and which entereth into that within the veil; whither the forerunner is for us entered, even Jesus, made an high priest forever after the order of Melchizedek" (6:19–20). Hence the anchor and the cross belong together, at the altar where Christ, under the species of bread and wine, is priest and God and sacrifice.

The whole work of art nestles in a cradle of branches and leaves. Beneath the altar, in a long scroll, are sculpted, in low relief, words in Portuguese, telling us that the sculpture was made by Father John Silva, in honor of Christ and his Church.

But the most striking feature of this sculpture is this: the whole edifice cannot weigh more than an ounce or two. Father Silva carved it from the spongy pith of a fig tree. With a razor that could make shavings as thin as breath, he must have spent hundreds of hours on that work of love, simply for the joy of it—and, as the Benedictine monks did, to share with other men the fruits of his contemplation. You could crush it in an instant in the palm of your hand, but the human spirit that conceived and executed that work—not the spirit of bondage, but the spirit of freedom, whereby we cry, "Abba, Father!"—that spirit we cannot quite crush, though we do our best to thwart it. Secular schools thwart it, when they reject beauty and view all works of the human spirit as the compulsions of political determinism. The museum curators themselves did not understand the sculpture; their placards note, obtusely, that Roman Catholicism is still "important" for the culture of Cape Verde. They translate Father Silva's signature, but they do not translate the words of consecration.

Built for the Lord

That afternoon we drove to the north end of New Bedford, now the rough end of the city, with buildings abandoned or in need of repair, and streets strewn with litter. But it was not always so. In the middle of one old French neighborhood rises the towering red stone church of St. Anthony of Padua, who was also, as all Portuguese know, St. Anthony of Lisbon, his birthplace. The doors were locked—I am sure that a hundred years ago we would have enjoyed the freedom of the church, but not in these days when we have lost so many of the ordinary human things. But it is a mighty edifice, with red and white stones set in diamond patterns beneath the towers, and an enormous arch over the main portal, with these words carved in bold relief: AEDIFICARUNT DOMINO SANCTI ANTONII OPIFICES: "The workmen of Saint Anthony built [this] for the Lord."

The inscription does not say, "The people of Saint Anthony's parish hired a crew of construction workers to build this church," although they did hire two architects and no doubt other workmen too. It says that the men themselves built it—with their own hands and shoulders and backs. They built it for the Lord. "Except the Lord build the house," says the Psalmist, "they labor in vain that build it."

We might say more. Except it is for the Lord, such a house will never be built at all. Freely did the men build, as freely as Father Silva carved. The one work of art must weigh a thousand tons; the other, a puff of wind could undo. But they are both works performed in that spirit of liberty that man longs for, and that the Church is the last institution left standing to defend. It is the liberty to love what is beautiful and good for its own sake, not for its utility, and certainly not for the fleeting pleasure it gives to the idle tourist. It is the liberty to be fully human, and it is the liberty to pray.

The Lord Must Build

Now then, how can this defense of what is human and free be made manifest in a Christian university? Newman was careful to keep things and their ends well defined. The object of a liberal education, he said, was not to make a saint, or a merchant, but to make the gentleman, a man whose experience with the humane letters in languages classical and modern would lend him a wide vista for sane and sober judgment. Such a man's mind, says Newman,

is almost prophetic from its knowledge of history; it is almost heart-searching from its knowledge of human nature; it has almost supernatural charity from its freedom from littleness and prejudice; it has almost the repose of faith, because nothing can startle it; it has almost the beauty and harmony of heavenly contemplation, so intimate it is with the eternal order of things and the music of the spheres.

My thoughts here turn to Pope Benedict XVI, listening to his beloved Bach, or reading Dante, or thinking about the great saints and mystics of the last two thousand years, while writing a letter whose every word must be handled and turned and weighed, such was his care for the souls and the minds of those in his charge; while the journalists of the world scribbled away, hunters and hunted at once, pressed by the need to produce, tangled in lies and ignorance, and hardly able to write a single sentence worthy of a man of liberal education.

So far, Newman seems to separate liberal from Christian education, and almost imply that you can have that freedom on its natural terms, without the faith. The Lord need not build the house. But that would be to mistake him; and here I owe a debt to the theologian Reinhard Huetter, who has argued that, according to Newman, without theology to make sense of the other fields of knowledge and to unite them, the university itself will cease to exist, though the deceptive name will remain. The university degenerates into a utilitarian polytechnicum, filled with people who make their particular fields of study, their particular crafts, usurp the whole universe.

If there is a God, Newman argues, and if by God we mean not only what the Scriptures mean but also what the great natural theologians among the pagans mean, then he has so "implicated Himself" with the world, "and taken it into His very bosom, by His presence in it, His providence over it, His impressions upon it, and His influences through it," that we cannot shut our eyes to theology "without prejudice to truth of every kind, physical, metaphysical, historical, and moral; for it bears upon all truth."

Unreal Knowledge

The implications for the humanities are clear, if one keeps in mind the revelation, known in a shadowy way even by the Greeks, that man is made free, in the image of the God who creates freely, out of love, untouched by the least necessity. Suppose a university professor—whether of politics, economics, literature, history, or the natural sciences—excludes from the outset this truth, that man is free. Such a man, says Newman, would fall to "a one-sided, radically false view of the things which he discussed," taking "his own study to be the key of everything that takes place on the face of the earth."

It would not be his study in itself that was untrue. Chemistry is still chemistry, and economics still economics. But his "so-called knowledge," says Newman, would be "unreal," since "he would be deciding on facts by means of theories," exactly what, I might say, the Marxist biologist Lysenko did, when he tried to compel the birds and the bees to obey the dictates of dialectical materialism, but the birds and the bees had better things to do, and went about their God-ordained business quite as if there never had been a communist in the world.

The humanities themselves have been partners in crime, conspiring first at their enslavement and then their demise. Return to the altarpiece fashioned by Father Silva. No sane person asks, "What did the priest think to realize by this work, in terms of political power?" Obviously, if you are after political power, there are nearer ways to work than by spending many hours of the day and night hunched over a handful of bark. No sane person asks, "How is this work situated in the perennial fight for the rights of women?" That would be like asking what money you could earn by taking a walk in a garden, or whether the green was as tasty as the red. The question hardly admits of an answer. It is not at all to the point. Yet that describes most of the "hot," "cutting edge," "trailblazing" work in the humanities, at least if letters of recommendation are evidence, or the advertisements on the jackets of scholarly books. It isn't so much that it is wrong, as that it is unreal.

Restoring the Human

We once interviewed a very nice young man for a position in our English department, to teach medieval literature. He was a Chaucer scholar, without an inkling of what the Scriptures and the Christian faith are all about. He wasn't hostile; it's just that he had not had a real education—an education in the reality of the very thing he proposed to study, the poetry of the Middle Ages. He therefore was a walking and talking example of what Newman warned against.

When theology is drummed out of the curriculum—and, I will add, when all of the noblest aspirations of the human spirit are ignored—then the place it once occupied does not remain empty. The other disciplines rush in where the angels once trod, and those other disciplines deal principally in things, or with man only insofar as he can be reduced to a thing. In this young man's case, economic determinism rushed in. He could speak forever about how Chaucer attempted to use his poetry to make for himself a nice career at court. It is rather sad when one thinks about it; a young man of sharp wit can imagine nothing more glorious than a career, and interprets the rest of the world accordingly.

But to take that view of The Canterbury Tales is to be treating of a thing that does not exist, an imaginary economic artifact, and not the actual work of art. It is as if one had been present when Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead, and could think of nothing better to ask than whether Lazarus was a Pharisee or a Sadducee. The headlines of the New Jerusalem Times the next day read, "Prophet Raises Man from Dead; Electoral Implications Unclear."

The Church is still, of course, in the business of raising men from the dead; but if she is to do her work, there must be men to raise, that is, beings recognizably human, despite the shoulders bent and the faces smudged by sin. That is where the humanities come in; and for us especially, as it was already for Newman, that means insisting on the very existence of man, and affirming his dignity. We professors of poetry cannot raise men to Paradise, but we can help break them of the compulsions of Hell. We cannot elevate them beyond the human, but we can help restore the human at least. We may be, if it isn't presumptuous to say so, fellow workers upon the mountain of Purgatory. And it is to that brilliant work that I turn now.

Gaze Directed Heavenward

To us who have nearly lost any sense of what the study of poetry, history, and philosophy are for, Dante has given us an inestimable gift, in the very structure of his realm of purgation. Purgatory is not beneath the earth. It is not above the earth. It is upon the earth, and it is a mountain, ascending toward the heavens. It is of the essence of man's life on earth to be so oriented; we cannot be more true to the earth and to our common humanity than when we climb that holy mountain. That is why, at the beginning of the Purgatory, Dante does not tell us exactly where we are, and does not have his pilgrim namesake speak with Virgil, until he directs our gaze heavenward:

Sweet sapphire of the morning in the east,

gathering in the starlit face of Heaven,

pure from the zenith to the nearest ring,Renewed my joy in looking on the skies

as soon as I had come from the dead air

that had saddened my heart and dimmed my eyes.The radiant planet fostering love like rain

made all the orient heavens laugh with light,

veiling the starry Fishes in her train.I turned to the right hand, and set my mind

to scan the southern pole, and saw four stars

no one has looked on since the first mankind.The heavens seemed delighted in their flame!

O widowed region of the northern stars,

you who have been deprived the sight of them!

The pilgrim here beholds three beautiful things of heaven, and the three combine to instruct us not only in where we are going, but how we are to go; Dante holds before our gaze not only the glory of blessedness, but the sweetness of the human journey. The first object is the color of the early morning sky, its rich sapphire in the hour before the dawn as Dante looks east, towards Jerusalem and the risen Christ. No doubt Dante wishes us to think of Mary, and the deep blue of her robes as depicted in Christian paintings and illuminations. She, the humble woman of Nazareth, fathoms more profoundly the being of God than does any other creature, as Dante will say in Paradise; and the sky itself, the vault over the humble earth, is meant to be beheld from the earth, and is involved with earth, as God is involved with man.

In that deep blue, Dante beholds the second object of beauty, the morning star, the planet Venus, che d'amar conforta, he says, that fosters love. Christ is the morning star that never sets, as is sung in the great hymn of the eve of Easter, the Exsultet, but here Dante is thinking also of all beautiful creatures that move our hearts to love, and specifically the beautiful woman, Beatrice, in whose praise he wrote his youthful rhymes of love. It is not possible here to separate a supposedly earthly or, to use an ugly word for a cramped idea, secular love from the heavenly love, since Venus herself faceva tutto rider l'oriente, "made all the orient heavens laugh with light."

Then Dante turns southward, and sees four bright stars that no man has seen since the fall of Adam. Dante takes care in the Purgatory to let us know that these stars represent the four cardinal virtues—temperance, courage, prudence, and justice—the four that Virgil swears to have followed without fault. They prepare us for the dance of the four virtues at the summit of the mountain, after Dante has been washed clean in the River Lethe; those ladies will lead the pilgrim to their three fellows, Faith, Hope, and Charity, so that the poet may finally behold the second beauty which Beatrice has not yet shown him—the beauty of her joy, her smile.

Oriented Toward Love

If we follow Dante's cue, we see that we cannot, in the end, talk sensibly of earth without looking to heaven. To put it another way, we cannot have a really human study of history or poetry or philosophy, or any of the natural sciences, while remaining fixed under the low ceiling of materialism; when we cease to look up, we cease to look at all. That is why, I believe, Dante accompanies the restoration of health to sinful man with the restoration of poetry—the poetry of love. Beneath the protected realm of Limbo in Hell, there are no discussions of poetry at all, or of art. In Paradise, theology reigns triumphant, and poetry, though not forgotten, recedes from our attention. Not so in Purgatory. In Purgatory—again, that infirmary where we recover what is most human—Dante meets poets and artists and singers everywhere, and even at the top of the mountain, in earthly Paradise, without any prompting, Matelda graciously suggests that the ancient poets

in their melodies of old

may have dreamed on Parnassus of this spot,

singing about the happy age of gold.For here the human race was innocent;

forever spring, and fruit upon the vine.

This is the nectar which the poets meant.

Her words bring a gentle smile to the lips of Virgil and Statius, who stand behind Dante, listening quietly.

I do not believe that Dante's concentration upon the nature and the aim of poetry is incidental; I do not believe he said to himself, "Hell does not deserve it, and Paradise is beyond it." Consider Dante's notable meeting with a poet whom he criticized severely, Bonagiunta of Lucca. Dante and Virgil and Statius are making their way along the terrace of gluttony, when one of the emaciated spirits looks intently upon Dante, prophesies that he will derive some comfort from a good woman in Lucca when his fellow Florentines drive him into exile, and then asks him the question that nobody in Hell ever asks:

"But do I see the introducer of

the new songs, and the verses which begin,

'Ladies who have intelligence of love'?"Said I to him, "I'm one who takes the pen

when Love breathes wisdom into me, and go

finding the signs for what he speaks within."

Bonagiunta is deeply satisfied with this response, and affirms that that allegiance to the indwelling Spirit of love was what he and his fellow poets lacked; it was not their manner that caused them to miss the dolce stil novo, "the sweet new style," but their failure to turn to Love for direction. Bonagiunta had satirized the stilnovisti for inserting into their love poetry terms borrowed from the schools, from theology and philosophy. Here Dante makes him correct himself. Terms may be used artfully or clumsily, but the whole orientation of poetry is toward love—and love turns our gaze heavenward.

Cavalcanti's Obtuseness

I should like to turn now to what I think is, in the Purgatory, the sweetest and most surprising moment of healing for the humanities. Dante had hinted, in the Inferno, that his best friend and fellow poet, Guido Cavalcanti, may be destined to lose the good of the intellect. You may recall how Cavalcanti's father, in Canto 10, suddenly interrupts Dante's conversation with the Florentine powerbroker, Farinata, to ask about his son. If here, he says, you are traversing this dungeon

through power of genius at its height,

Where is my son? Why is he not with you?

Shall we call Cavalcanti a Baconian, a believer in untrammeled human power, with no aim beyond the domination of nature? He seems oblivious to any danger to his son's soul; it is enough for Cavalcanti, proud father that he is, that Guido show the brilliance of his mind, his ingegno, his "power of genius." The contrast between that view of humane study and Dante's may be seen in the first lines of the Purgatory, when Dante says la navicella del mio ingegno, his "little ship of ingenuity," his "little bark of inborn powers," now must hoist the sail to speed through better waters; and again we recall that there is no sailing without the stars to guide us.

So Dante must correct the old man. He is not traversing through Hell through power of genius at its height. He is being led through Hell by his companion, Virgil, for the sake of "one your Guido, maybe, held in scorn"—for Beatrice, as I read it, or Christ; for Guido Cavalcanti had written most pessimistically of love, calling it an irresistible and ultimately destructive force.

But Guido's father hears none of that; he hears only the past tense of Dante's verb, held, and slumps back into his tomb, assuming that Guido has died, that the sweet sunlight has ceased to strike his eyes. It does not occur to him to consider that if Guido has died and if he is not in Hell, then he is in a place where he beholds that sweet sunlight still, if not a light that is infinitely sweeter and brighter. Cavalcanti's obtuseness here, his shortsightedness, the smothering of the imagination of one who was by all accounts a most intelligent man, is well represented by the lids that will seal the coffins of these heretics at the Last Day, when, as Farinata says, "the future ends, and judgment shuts the door."

Hope for Guido

University life, even the study of the humanities, is like the death within death that Cavalcanti and the materialist heretics will experience in those cramped little tombs, unless it is open to the skies. But Dante was not willing to let that judgment against his friend remain. He still held out hope that Guido could be redeemed. And here I must cite Guido's sweetest poem, a simple and intensely erotic pastoral lyric, not philosophical, not tormented with doubts. Here are the initial couplet and the first stanza:

In un' boschetto trovai pastorella,

Piu che la stella bella, al mi' parere.In a small grove I found a shepherdess,

lovelier, in my eyes, than a star above.

Blond hair she had and woven in little curls,

love in her eyes, and rose-flush in the cheek;

she led her lambs to pasture with her staff;

her feet were shoeless, glistening with the dew;

and she was singing as if she were in love.

She was adorned with all that gives delight.

It is an exquisite work, as witness the delicate internal rhyme in the first couplet—with a caesura following that word stella, star; the heavenly object that Guido's father will nevermore behold. Cantava come fosse innamorata, "she was singing as if she were in love"; that is the key line. She was singing. There is no singing in Hell, but there is plenty of singing all up and down the mountain of Purgatory. Cantare amantis est, says Augustine; singing is what the lover does, and therefore song draws near to the heart of prayer. It may not be a holy thing to write a song in honor of a beautiful woman, but it is a human thing, and, like the mountain of Purgatory, it points toward a beauty and a love beyond itself.

And that is why Dante will not leave his friend's poetry behind. Matelda, that lovely guide in earthly Paradise, has, as we have seen, suggested to the ancient poets that their dreaming of the Golden Age had as its object the land she now walks. That canto ends with the smiling of Virgil and Statius—their pagan poetry is brought into the great song of love; and in the next canto, it is Guido's turn. For Dante begins with these words: Cantando come donna inamorata; "Then as a woman sings who sings in love."

Guido had written, of his imaginary shepherdess, Cantava come fosse innamorata, using the subjunctive mood: she was singing as if she were in love. Dante has replaced the subjunctive with the indicative: Cantando come donna innamorata; "Then as a woman sings who sings in love." The implication is clear. This woman is indeed in love, and that is why she sings. She is in love both with the sweet earth, whence she culls her flowers, and with the Lord of earth and heaven. She is Leah the active, to Rachel the contemplative. She is the forerunner John, to the savior Christ. She brings Dante to the place where he will look upon Beatrice.

Where Freedom Is Found

Why study poetry, or any of the humanities, in our educational mills, if it means only toil in the harnesses of utility? And that is what it must be, without the stars above to guide us. I say again: the Church is for man, because she is for God. Dante's great poem, and the soaring towers of a stone church in New Bedford, raised up by that extraordinary creature known as a man in prayer, and that delicate sculpture by a priest dwelling in the reflected light of eternity, they all testify to where true freedom is to be found. •

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on education from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor