The Colossus of Constantine

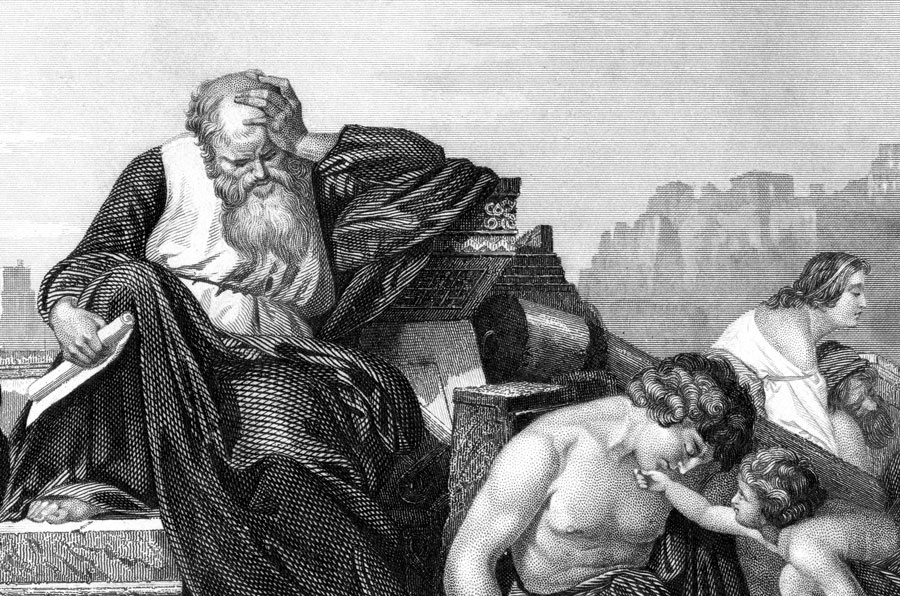

A lot can happen to a work of art in 1,700 years. Consider the Colossus of Constantine: what remains of it today are a colossal marble head, standing over seven feet tall; a right arm and, oddly, two right hands; a left kneecap and shin; and both feet, complete with callused toes and sandals, a soldier's feet. Such a curious collection of fragments raises many of the kinds of questions art historians must ask themselves. What did this look like originally, before it fell prey to Time the destroyer and other varieties of vandals? Why did it look that way? And what was it meant to convey in its own time?

Let us begin by piecing together what we know of its history, and work deductively from there. The size of the head suggests that the figure of Constantine, even if seated, would have measured over forty feet high. (For comparison, the seated Lincoln in his monument in Washington is nineteen feet high, less than half the size of Constantine.) A solid marble statue of that size would defy even modern-day moving equipment, so it must have been an acrolith, a statue with sculpted marble parts attached to a framework of wood or brick, covered with clothing or drapery cast in metal. If the marble pieces were reassembled on such a framework, they would likely show that Constantine had himself portrayed in the same pose as the Capitoline Jupiter Optimus Maximus, the most important sculpture in ancient Rome.

The Constantine fragments were found near the ruins of the Basilica of Maxentius and moved to the Capitoline Hill in Rome in 1486 by no less a personage than Michelangelo. Later they were moved to the courtyard of the Capitoline Museum, where they remain today (more fragments were discovered in 1951). But originally the Colossus was meant to be housed in the apse of the Basilica of Maxentius, an ambitious architectural project planned and begun by Constantine's fellow tetrarch, Maxentius.

THIS ARTICLE ONLY AVAILABLE TO SUBSCRIBERS.

FOR QUICK ACCESS:

Mary Elizabeth Podles is the retired curator of Renaissance and Baroque art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. She is the author of A Thousand Words: Reflections on Art and Christianity (St. James Press, 2023). She and her husband Leon, a Touchstone senior editor, have six children and live in Baltimore, Maryland. She is a contributing editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on art from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor