Feature

The European Disunion

Benedict XVI on the Crisis of Faith & Reason

There are few more insightful observers of Europe’s problems than the scholar-pope Joseph Ratzinger. Master of eight modern and ancient languages, an accomplished classical pianist, Mozart devotee, member of the Académie Française, and one of the world’s leading theologians, Benedict XVI has not merely written extensively about European history. He has also lived through some of modern Europe’s defining experiences, ranging from the Nazi dictatorship to May 1968.

But perhaps Benedict’s most striking contribution to contemporary discussion about Europe is his contention that Europe’s problems do not lie primarily in its increasingly bureaucratized political and economic arrangements—as damaging as he says they are. Rather, he insists that Europe’s difficulties ultimately flow from a crisis of faith and reason.

It is true, he remarks, that the precise relationship between reason and faith “was never quite beyond dispute” for Christians, even after Aquinas. But what was not questioned until the late medieval period was the essential compatibility between the two realms of knowledge.

Thereafter, Benedict holds, the legitimate autonomy of the sciences that Catholicism has always recognized as essential to these disciplines’ integrity developed into a type of separatism. While acknowledging that the church’s handling of the Galileo case misled many into imagining that science and faith were opposed, he maintains that the split was also driven by some thinkers’ exaggerated rationalism, especially that of Descartes, Spinoza, Kant, and—as he reminded readers of his encyclical Spe Salvi, Francis Bacon. The distinction between ratio (the empirical realm of what can be done) and intellectus (reason that contemplates “the deeper [meaning] of being”) was lost, with only ratio remaining. Reason was thus, he argues, reduced to experimental study, and questions of morality and faith relegated to the subjective realm.

Tragic Separation

The drama of this separation was played out in Western intellectual history. While Hegel, Benedict suggests, attempted to return faith to its correct place in philosophical reasoning, he tried to transform faith into reason, thereby dissolving faith qua faith. Marx, Benedict claims, took the opposite path by insisting that the only valid form of knowledge was positivist scientific knowledge, thereby making the very idea of God irrelevant.

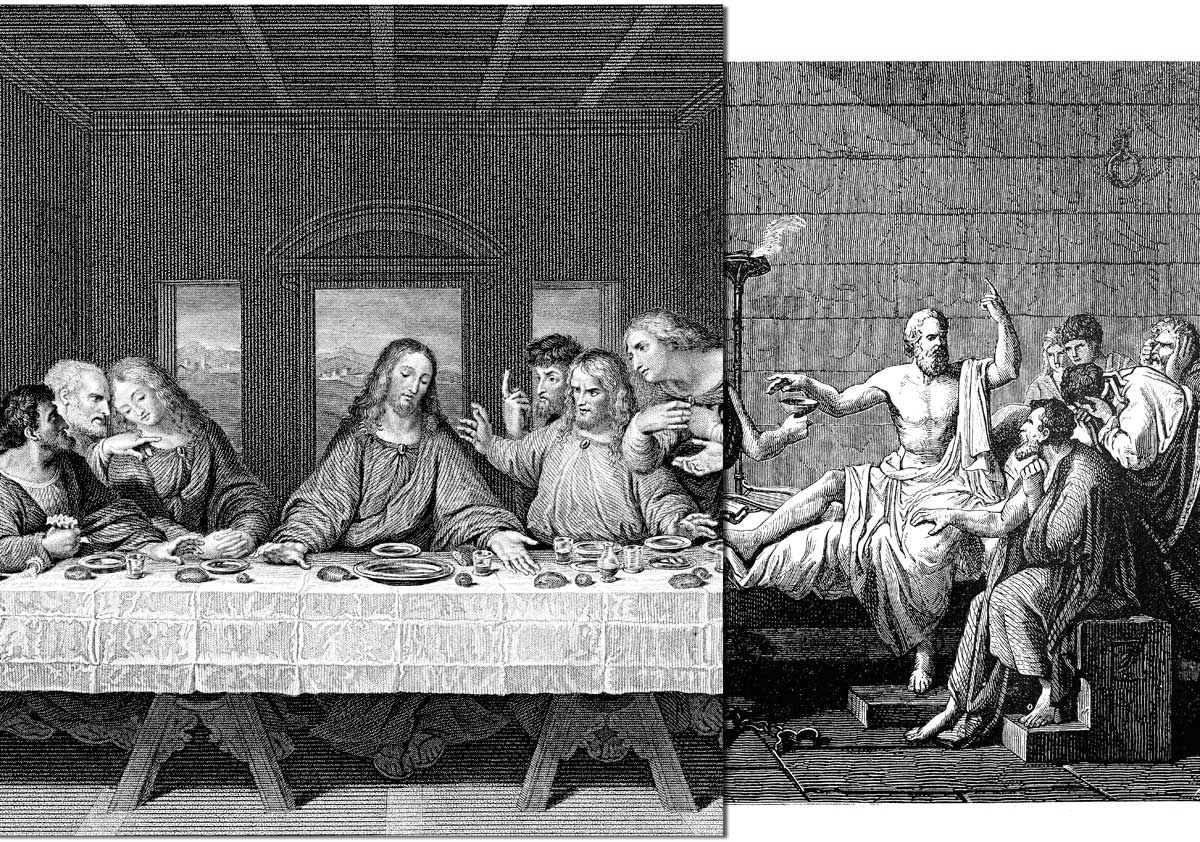

The tragedy, to Benedict’s mind, is that there was nothing necessary about this separation. The modern sciences, he notes, first flourished in medieval universities built by the church and gained much of their precision through their encounter with Catholic theology and logic. Catholicism always understood itself “to be the religion of the Logos,” whose Jewish-theological and Greek-philosophical antecedents undermined the highly superstitious pagan religions that obstructed Europeans’ search for truth.

Part of the problem, Benedict claims, was that by the seventeenth century, “the voice of reason had become excessively tame” within the church. The Enlightenment had the merit of forcing Catholicism to re-focus attention upon the value attached to reason by Scripture, the church fathers, and medieval theologians, thereby restoring reason to its proper place in Christian discourse.

Yet, according to Benedict, the radical separation of reason and faith associated with certain streams of modernity has considerably damaged both faith and reason.

Deprived of reason, he states, faith has in many instances been reduced to “feeling and experience,” thereby weakening faith’s claims as rational, universal propositions. This has caused faith in some cases to degenerate into superstition. Without reason, Benedict holds, believers become susceptible to fanaticism, precisely because God becomes for them an idol when they are in fact worshiping nothing more than their own will.

But splintering faith and reason has also created pathologies of reason. Benedict notes that reason’s “turning away from the ultimate questions has rendered it insignificant and boring” precisely because it “has resigned its competence where the keys to life are concerned: good and evil, death and immortality.” It also results in absurdities such as scientists arguing that “man . . . does not possess any liberty,” while ignoring the fact that scientific research cannot even occur without people freely choosing to pursue it. Reason loses its orientation, Benedict stresses, when “the guiding principle is that man’s capability determines what he does”: i.e., the non sequitur that if you know how to do something, you are permitted to do it.

The Real Regensburg

Many of these thoughts were crystallized in Benedict’s famous 2006 Regensburg lecture. Unfortunately, the controversies generated by the somewhat puzzling reactions to this speech distracted attention away from Regensburg’s real import. Certainly Islam’s theological dilemmas were a focus of the speech, but the Regensburg lecture—which will surely be remembered as being as important an address as Solzhenitsyn’s 1978 Harvard speech—also concerned Europe’s crisis of faith and reason.

At Regensburg, Benedict maintained that Christianity’s “inner rapprochement between biblical faith and Greek philosophical inquiry was an event of decisive importance” but not only in the history of religion. “This convergence,” he says, “with the subsequent addition of the Roman heritage, [also] created Europe and remains the foundation of what can rightly be called Europe.”

The implication is that any sundering of the link between faith and reason in Europe would mean that Europe itself would begin to lose its distinctive identity. In other words, Europe without a Christianity that coherently integrates faith and reason is no longer a European Europe.

Interestingly, Benedict also noted at Regensburg that this break did not begin with the Enlightenment. He maintains that the split first appeared with the voluntaristic ideas associated with the medieval theologian Dun Scotus. The claim that God could act unreasonably corroded the synthesis of faith and reason achieved by Augustine and Aquinas.

Another pre-Enlightenment Christian European event contributing to this development, he argues, was the tendency of some Reformation thinkers to view metaphysics as contrary to the principle of sola scriptura, thus necessitating Christian faith’s liberation from an allegedly alien Greek straightjacket.

Splintering Truth & Freedom

A later Christian contribution to the breaking of Europe’s synthesis of faith and reason was the liberal theology that flourished in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This theology sought to “liberate” faith by subordinating it to the claims of the positive sciences. As a result, Benedict states, much of European Christianity was stripped of its metaphysical and rational content, and reduced to mere humanitarianism.

Benedict’s attention to the faith-and-reason question is closely associated with another issue that, to his mind, has contributed to Europe’s problems: the separation of truth and freedom. In one of his pre-pontifical books, Truth and Tolerance, Benedict argues that modern Europe’s attitude toward nonscientific truth is summarized by Pontius Pilate’s question: “What is truth?” This situation, he suggests elsewhere, owes something to Enlightenment culture, which is “substantially defined by the rights to liberty” and “its starting point,” which regards liberty as “a fundamental value and the criterion of everything else.”

This has positive consequences, he notes, such as furthering Christianity’s radical limitation of state power. It also, however, creates tensions, such as between “a woman’s right to freedom and the unborn child’s right to life.” These conflicts, Benedict argues, emerge because continental Europe’s Enlightenment conception of liberty “is either badly defined or not defined at all.”

This issue of definition arises because some Enlightenment thinkers detached liberty from man’s innate capacity to know truth, especially those moral and metaphysical truths that transcend—without contradicting—scientific data. Benedict agrees that this development owes something to concerns that truth claims have been used by many, including Christians, to unjustly coerce people. To some modern European minds, relativism is therefore “the real guarantee of freedom.”

Reason in Nature

Reflecting upon such developments, Benedict remarks that the idea of natural law—which is how the pre-modern world philosophically reconciled freedom and truth—presupposes “a concept of ‘nature’ in which nature and reason interlock: nature itself is rational.” But for some moderns, human nature “ per se is not rational.”

The problem, he suggests, is that having denied that human nature itself is rational and having reduced reason to the positive sciences, the question of what is rational automatically narrows to issues of technological effectiveness. Man himself becomes a product to be shaped rationally and thus subject to the control of others.

The effects, Benedict insists, are positively anti-human. They exhibit themselves in contemporary European ways of thinking about moral questions.

Abolishing the notion that moral absolutes are inscribed into man’s very reason leaves utilitarianism as the dominant ethical system, and leaves people trying to determine what they should do by engaging in literally impossible calculations of all the possible good and evil effects of their choices. This necessitates arbitrary and therefore unreasonable decisions about what to weigh and how much to weigh it. Prioritizing usefulness over truth inevitably results in some people becoming the slaves of those who decide what is useful and what is not.

Damage to Conscience

Then there is the damage done to a coherent idea of conscience. Recalling Christianity’s teaching that the informed Christian conscience gives us freedom precisely because it is the primordial voice of God’s truth written into man’s reason, Benedict believes European modernity’s sundering of truth and freedom has left many people convinced that conscience amounts to “an independent and exclusive capacity to decide what is good and evil” quite separate from the moral truth revealed through faith and reason.

Benedict suggests that this encourages people to believe there can be no such thing as an erroneous conscience, precisely because man’s free choices are no longer subject to the demands of truth. Conscience is no longer understood as “a window that makes it possible for man to see the truth that is common to all of us.” Instead, conscience becomes “a cloak thrown around human subjectivity, allowing man to elude the clutches of reality.”

Errors arising from freedom’s detachment from truth are not confined to philosophy. This detachment also undermines the coherence of some of the fruits modern Europe claims as its own. Benedict observes that in those democracies where metaphysical truths are rejected as threats to liberty, majority decision quickly occupies “the position of ‘truth’” in political life.

To illustrate the effects of this, he refers to Hans Kelsen’s reflections on Jesus’ trial. Kelsen presents Pontius Pilate as the perfect democrat. As soon as Pilate asks Christ, “What is truth,” he does not wait for Christ’s response but instead turns to the crowd for a decision. This, Kelsen states, is what should occur in a procedurally correct democracy based on skepticism of truth claims. Benedict, however, observes that Kelsen seems unconcerned that an innocent man is thereby condemned to death. But such is the logic of democratic freedom detached from truth.

Two Streams

Despite these problems, Benedict displays no nostalgia for a restored Christendom or a pre-modern world. Instead, he desires a reconfiguring of European modernity. This is possible, he suggests, if Europe returns to the origins of the modern movement for freedom. The Enlightenment was characterized by a desire for emancipation in Kant’s sense of subjecting any claims to authority to critical scrutiny. Hence, the only remaining authority was reason.

This trend, however, split into two streams. One, associated with Rousseau, “ultimately aims at complete freedom from any rule.” It is directed by an “anti-metaphysical” concept of nature, epitomized, in Benedict’s view, by Sartre’s claim that, unlike animals, man has “no nature.” This was taken to extremes by the French Revolution, and by Nietzschean, National Socialist and Marxist nihilism.

This positing of freedom as separate from truth leaves room for neither reason nor Christian faith. There is, however, another Enlightenment stream, which Benedict labels “the Anglo-Saxon trend.” This stream tends to ground liberty upon the reason inscribed in man’s nature.

Human rights, according to this vision, proceed from human nature and thus come from within man; they are not granted to him by the state. Human nature, in this Anglo-Saxon tradition, is more than just biology; “it is also a metaphysical idea: inherent in being itself there is an ethical and legal claim.” Such thoughts, Benedict holds, parallel the Christian concept of human nature.

Benedict believes that this particular modern understanding of liberty—perhaps associated with certain Scottish Enlightenment thinkers—has sufficient commonality with Catholicism’s vision of human nature, liberty, and rights that it offers some possibility of a meeting of minds. Both share a basic confidence in reason’s ability to make the truth known.

Freedom’s Content

There is, however, something Benedict believes Christianity as a religion can contribute to this stream of European modernity. Not even Kant, he writes, could “create the necessary certainty” required by societies valuing freedom on the basis of pure reason. Indeed, Kant insisted that God, freedom, and immortality were necessary postulates for human reason, without which moral incoherence would prevail.

Benedict affirms that “freedom requires content.” Democracy must have a “non-relativistic” center if it is not to degenerate into tyranny. Here he highlights Tocqueville’s insight that Christianity supplied the common ethical convictions needed by American democracy’s foundations. Elsewhere, he cites to the same end Tocqueville’s famous axiom: “Despotism may govern without faith, but liberty cannot.”

Benedict also argues that modernity’s achievements, including “the recognition and safeguarding of freedom of conscience, human rights, [and] freedom of science and scholarship” should be safeguarded, but without collapsing into “the abyss of a reason without transcendence that destroys its own freedom from within.” Here he believes that Europe can learn something from America’s experiment in ordered liberty.

Benedict is far from uncritical of American culture. Nonetheless, he observes that until recently, America avoided many of the fractious disputes that characterized relations between Christians and nonbelievers in continental Europe. Apart from attributing this to the American founders’ decision to have no established church, Benedict invokes Tocqueville’s observation that the “system of rules on which . . . this democracy is founded” functioned because of the Christian-inspired convictions pervading every level of American society.

Thus, Benedict holds, if Europe is to be Europe, carefully designed institutions are insufficient. “Alexis de Tocqueville,” he writes, “worked out in an impressive way that democracy depends far more on mœurs than on institute.” Without such convictions, “compulsion becomes a necessity [because] freedom presupposes conviction, [and] conviction [requires] education and moral awareness.” Hence, Benedict concludes, “when mœurs are left out of consideration we have not an increase in freedom but a preparation for tyranny.”

Two Suggestions

This observation leads him to two concrete suggestions: one directed to European Christians; the other to European nonbelievers. Insisting that a society’s fate always depends upon “its creative minorities,” he calls upon European Christians to give credibility to the Christian values that sustain freedom in European societies, first by defending their rational basis, but also by making “God credible in this world by means of the enlightened faith they live.”

In short, European Christians must not only think the truth. They must live it. As the Australian theologian Tracey Rowland observes in her book Ratzinger’s Faith, “It is one thing to be coerced into a ghetto, quite another to walk in meekly as if one deserves to be there.”

As for European nonbelievers, Benedict suggests that if they share his diagnosis of Europe’s problems, they might consider “revers[ing] the axiom of the Enlightenment and say: Even the one who does not succeed in . . . accepting the existence of God ought nevertheless to try to live . . . his life veluti si Deus daretur, as if God did indeed exist.” Recalling that this was the advice that Pascal—a Catholic writing at the time of the Enlightenment’s dawn—gave to his nonbelieving friends, Benedict insists that this path “does not impose limitations on anyone’s freedom; [rather] it gives support to all our human affairs and supplies a criterion of which human life stands sorely in need.”

As Ian Markham writes, “you cannot assume a rationality and then argue there is no foundation to that rationality. Either God and rationality go, or God and rationality stay. Either Nietzsche or Aquinas, that is [Europe’s] choice.”

It is America’s choice as well.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Philosophy from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor