Feature

Long Shadows of Eden

On Conservatism as Vexation, Vanity & Near Impossibility

I would like to admit from the outset what in any case you will soon detect: I am no political scientist, nor a sociologist, nor a lexicographer. No form of expertise warrants my pontificating about what conservatism is and whether or not it is possible. This is therefore a personal meditation (perhaps something of a lament) by someone who would like to find an outlet for his conservative temperament, but now fears that such a wish may be what the Preacher describes as chasing the wind or, in an older translation, as vanity and vexation of spirit.

The problem I confront has not always existed in the acute form in which we encounter it today. The poet T. S. Eliot defined his own conservatism in lapidary terms. He described himself as Anglo-Catholic in religion, classicist in literature, and royalist in politics. But that position was already being held more for rhetorical effect than for practical purposes. Consider for a moment another poet not much later than Eliot who wore those same colors (at least in religion and politics). I speak of the former British poet-laureate, John Betjeman.

Betjeman’s conservatism expressed itself not only in politics and religion but also in a life-long dedication to preserving English country life. His writings on rural life and architecture have implanted in the minds of more than one generation of Englishmen and tourists a poignant and powerful idea of what is often called “Betjeman’s England.” Think of melancholy churchyards, verdant meadows, and unspoiled villages.

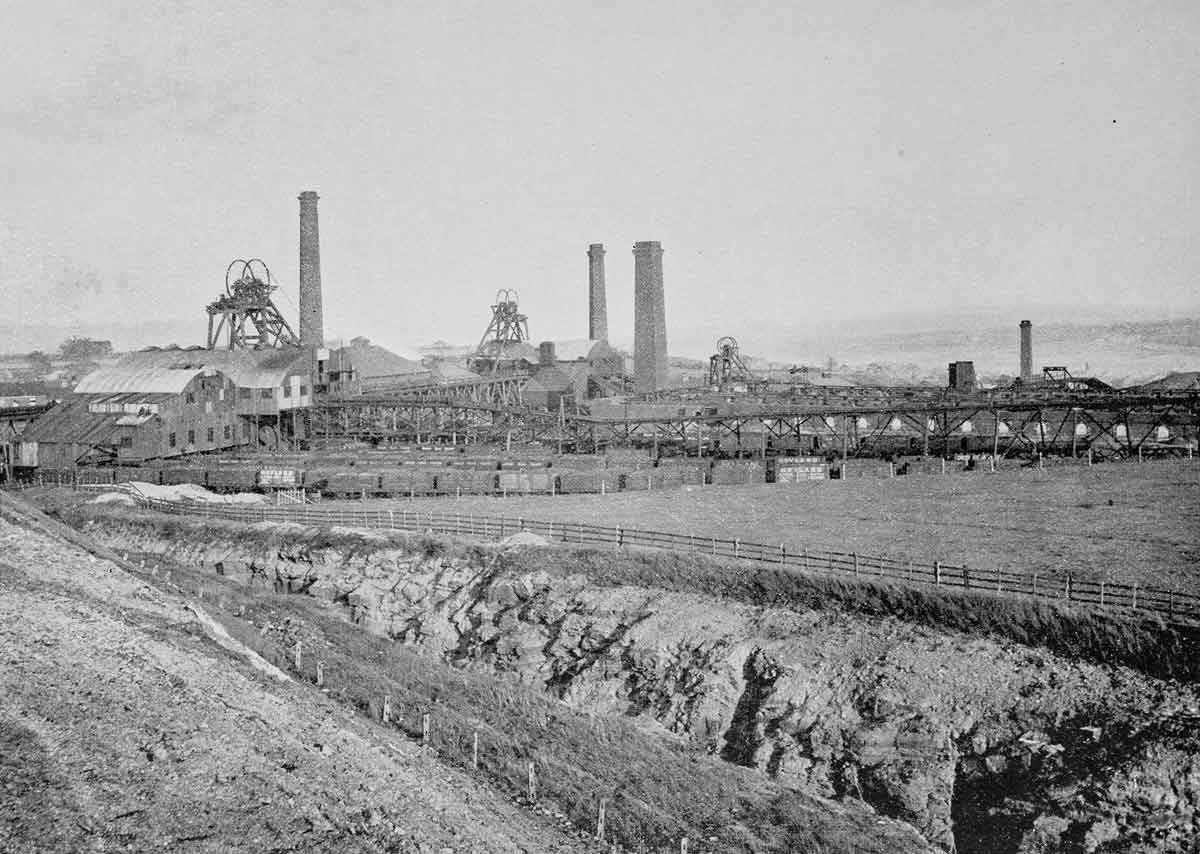

Consider now one of his poems, called “Slough,” published in 1937. To appreciate it, you should know that Slough is the name of an English industrial town that epitomized all the developments Betjeman loathed and feared in England. It begins:

Come friendly bombs and fall on Slough!

It isn’t fit for humans now,

There isn’t grass to graze a cow.

Swarm over, Death!

It continues in this way for four stanzas, but then asks the bombs to spare “the bald young clerks,” for

It’s not their fault that they are mad,

They’ve tasted Hell.

It’s not their fault they do not know

The birdsong from the radio,

It’s not their fault they often go

To Maidenhead

And talk of sport and makes of cars

In various bogus-Tudor bars

And daren’t look up and see the stars

But belch instead.

The poem finishes with another request for the bombs to fall on Slough.

This poem appeared in Betjeman’s 1937 collection Continual Dew (it can be found in his Collected Poems) and no doubt reflected some of the communism, and not a little of the cultural elitism, that were the fashion of the day. But what I want to draw your attention to is another attitude, one for which I can think of only an oxymoronic name: I want you to notice this poem’s “conservative extremism.” Betjeman’s imagery juxtaposes two towns: one lovely, but only present as a lingering image, the other repellent but right there in your face.

The first town is that of Tudor England, pastoral, close to the land, harvesting its food from nearby fields, local and communitarian, without gadgets, but harmoniously interacting with its own flora and fauna. It was to the celebration and protection of the vestiges of such towns and their ways of life that Betjeman devoted a portion of his own work and thought.

However, superimposed on this idyll, and almost effacing it, is an artificial, ugly town, whose brutal economy calls into existence ignorant Hobbesian men and women. Their lives are not worth living, and their artifacts are worthy of nothing but derision and, if possible, destruction. This double vision, this hatred of the city that is and veneration of the one that is not, is what I am trying to capture by the oxymoron conservative extremism.

My question is this: How could someone of such conservative tendencies as John Betjeman gleefully implore bombs to fall on a city in his own beloved country? Not that there is necessarily any difficulty in sympathizing with Betjeman’s attitude toward Slough, or its North American equivalents. I, at least, do not find that sentiment difficult to second. The challenge lies in justifying one’s sympathy on conservative principles.

When you have visited ghettos or slums, or the affluent ghettos and slums that we often call suburbs, or, for the sake of direct comparison with Slough, our sprawling and dirty industrial towns, have you never wanted to say, with Betjeman, “Come gentle bombs . . . mess up the mess they call a town”? Have you not wondered whether such architectural and social abominations as many of our communities represent can really be the fruit of 2,000 years of Christian civilization? Well, if you have wondered that, you can perhaps imagine at some point saying, “Let the bombs begin to fall so that we may start over again.”

Conservative Slough

Now, if you are a Marxist or an anarchist, we expect you to talk that way. But if you are a conservative, you are surely something of a puzzle. Such destructive wishes are not supposed to be so much as entertained among your thoughts. Can any conservative be justified in embracing them?

You may say that my question is not really very difficult to answer. Betjeman values an older, more traditional England and regards a town like Slough in the same way we would look at a rash on our own skin. We want to be rid of the rash in order to conserve the skin. Betjeman’s attitude is then perfectly consistent with conservatism. Slough should be purged, Betjeman thinks, in order that traditional England can continue in her traditions.

But should Betjeman not have been able to see, even in 1937, what is unmistakable today, that the old-world England he wanted to preserve existed only in the smallest vestiges and only by virtue of an active tourist industry? Was it not obvious, as I think no one today fails to see, that Slough was the norm rather than the exception, the skin itself, not just a rash on its surface? Slough pays the tourists who keep old England going!

The old England we tourists go to see is like the American wild west: a product of restorations at best, but often also of fabrications, which only tourist dollars can support or justify. The sordid truth is that Britain today, like Canada today or America today, is Slough writ large. If you doubt me, then read Peter Hitchens’s recent book, The Abolition of Britain, and doubt no more.

If Betjeman had come to realize that his England was dependent on Slough, what would have become of his conservatism? He would find nothing fit for conservation. Yet if he called down bombs on everything connected with Slough, there would not be enough left of England to support human life. People of Betjeman’s turn of mind do not really desire to conserve the things that are. They are often the ones most bent on changing them.

They may well be royalist, classicist, and high-church in their sympathies, but those dispositions have a paradoxical effect. Because they are so out of keeping with the common assumptions of contemporary life, they transform whoever embraces them into a radical utopian, an extremist.

Unconservable Slough

I chose Betjeman and his poem as a case in point to ease us into a difficult and interesting question: Can we be conservatives, even if we want to? Many, perhaps even most, North Americans do not want to be. That is fine. But you may for that very reason take a particular interest in thinking about, not to say gloating over, the sorrows of those who do.

Now here is a clever reply to my puzzle that someone might suggest. Forget about conserving Tudor villages, he will say. If you have to conserve something, why not Slough itself?

But no. The obstacle to conservatism I am trying to get you to see is more formidable than this debater’s retort implies. Slough today is unconservable for reasons going beyond the fact that conservatives do not love it. Like any thriving American industrial town, Slough has hurtled through many revolutions since 1937 and is transforming itself today. Between 1937 and now, its mind has been flattened by television, and its populace has been forcibly diversified by immigration and socially atomized by the Internet. Slough, like its American counterparts, will be host to every trendy deformity there is.

Therefore, it will not only be the last thing a conservative would wish to conserve, but its conservation will also be a theoretical impossibility because Slough is not a constant. Nothing is. The West today has embraced the ideal of perpetual revolution driven by technology. The Slough of 1937 would have been as impossible to conserve as the vestiges of Tudor civilization. And what we now call Slough—indeed any thriving urban center today—is really only an idealization. It is a construction site, built and unbuilt every day. It is a shape-shifting monument to change.

Slough is the world. And in it evolving technology constantly turns our lives and expectations upside down, proving the mutability of even those aspects of life we used to think permanent and necessary. Technological change pressures us toward a moral flexibility that is inconsistent with the dogmatic, moral, and religious traditions to which conservatives nevertheless stubbornly cling. That’s rather abstract and a bit of a mouthful. Take a controversial, but, I hope, illuminating example.

Consider the colossal transformation of public attitudes that began with the availability of efficient birth control in the 1960s, a development that only the Catholic Church in its encyclical Humanae Vitae had the foresight to oppose. From there we have seen the unstoppable rise and acceptance of abortion and feminism in the seventies, of homosexual rights and polymorphous sexuality in the eighties and nineties, and the introduction of homosexual marriage today, with pedophiles and zoophiles waiting eagerly and conspicuously in the wings. Divorce, day care, and the epidemic of AIDS are among the unforeseen consequences of these developments. For those with eyes to see, “the pill” provides a striking illustration of the connection between new technology and new morality.

From horizon to horizon, our world today is Slough, and Slough is in constant flux. It offers us little we conservatives would wish to conserve and nothing we could conserve even if we chose. Where, then, is there any fit object to which conservatives might apply their attention?

Piecemeal Preservation

Perhaps the answer is that, although general conservatism is impossible, there is still an opportunity for what might be called “piecemeal” or “institutional” conservatism. We can attempt to rescue our schools, our universities, or our churches from contamination by the trendy diseases of the age.

But this path is also a hard one. There would not be the global problem already described if our major institutions had somehow been unaffected by it. Do conservatives wish to preserve an army that sends women into combat, an Episcopal Church that ordains homosexual bishops, a university that has already embraced affirmative action for more than twenty years?

The Nobel-laureate of 2003, the South African J. M. Coetzee, won the Booker prize (the British equivalent of the Pulitzer) for telling the story of piecemeal or institutional depravity in his novel, Disgrace. The anti-hero is David Lurie, a sometime professor of English who, by the time we meet him, is reduced to professing the pseudo-subject of “Communications.” The polytechnical university that is Lurie’s employer considers literature to be a thing of the past. But in its affluence and labor-law impotence it agrees to carry such human fossils as -Professor Lurie through to retirement. It agrees, that is, subject to the proviso that they submit their judgment to the ever-changing orthodoxies of the moment.

For his part, Lurie looks ahead to some dreary years of pointless teaching before he can be pensioned into total insignificance. However, in a moment of rebellion he becomes, as he later says, a servant of Eros, and drifts into an affair with a student. Predictably, this sordid -episode goes wrong, and Lurie is caught in the moils of the university’s sexual harassment machine. The -inevitable kangaroo court is summoned, and, because Lurie cannot muster sufficient hypocrisy to pretend to respect it, his days as a professor come prematurely, ingloriously, to an end.

Disgrace is what his condition is called. From there, he drifts away into other institutional contexts in contemporary South Africa, finding in each one new disgraces. We see him in town, in the country, in a charitable institution. In no setting does he find much that can be redeemed or that is even stable. If Coetzee’s insights can be trusted, and rarely have I encountered a writer who hews so carefully to the facts, a conservative can get no purchase in South Africa today. But South Africa stands for the world.

Still, maybe Coetzee, for all his writerly skill, is not to be believed. His examination of the institutions of South Africa is, after all, neither exhaustive nor definitive. There are institutions that his novel overlooks, and even those he touches on might have something to say in their own defense.

Coetzee’s Omission

There is in fact one important institution that he omits considering altogether: the Roman Catholic Church. And if there is one organization that a conservative of Western European descent could conceivably adhere to, it is that church. Why do I say that, not being a member? (I am a Prayer Book Anglican.)

First, because there is something there to conserve: The original deposit of doctrine, the teachings of the saints as recounted in the Christian Bible, have been preserved there for two millennia. That is why the church can describe itself as “ semper eadem,” always the same. But Catholicism also admits that there has been a development in its doctrine, that insights have been gleaned with infinite patience by men of great learning over long centuries, and are represented in the accumulated wisdom of councils and papal statements throughout the ages. For that reason, the church is also entitled to describe itself as “ semper reformanda,” always to be reformed.

In order that reformation not misfire, however, there is within the church an office whose entire raison d’etre is to insure that any new doctrine will only be received as true when it is proved to be nothing more than an authoritative exposition of something already taught and believed. The office I refer to is, of course, that of the Sacred Magisterium. Now, an institution that is simultaneously semper eadem and semper reformanda is precisely where a conservative dreams of belonging, a place in which every change bows deeply to the past and every voyage brings you quickly home.

And so it is no wonder that thousands of conservatives have fled to the Roman Church. Refugees from Protestant churches that ordain women, or that encourage homosexual clergy, or, most recently, that are in favor of homosexual marriage and adoption have flowed into the Catholic Church in waves.

In spite of all its religious attractions, however, I believe that anyone who joins the Catholic Church solely in pursuit of a place to practice his conservatism would be making a mistake. The reason is simple. To be a faithful and orthodox Catholic today, one is obliged to be, in addition, a political extremist. This claim may surprise you, unless you have been following the recent encyclicals of Pope John Paul II. The media will not help you here, and neither will the liberal clergy.

They lack the patience to read the encyclicals, and perhaps in some cases the acumen to understand them. Otherwise, they would be denouncing the radicalism of Karol Wojtyla from the rooftops. Let me give two examples.

Papal Extremism

In the encyclical Evangelium vitae ( The Gospel of Life), the Holy Father writes the following (§62):

No circumstance, no purpose, no law whatsoever can ever make licit an act which is intrinsically illicit, since it is contrary to the Law of God which is written in every human heart, knowable by reason itself, and proclaimed by the Church.

Okay, you say. What’s so extreme about that? Well, consider what follows a few pages later (§72):

Laws which authorize and promote abortion and euthanasia are therefore radically opposed not only to the good of the individual but also to the common good; as such they are completely lacking in authentic juridical validity. . . . Consequently, a civil law authorizing abortion or euthanasia ceases by that very fact to be a true, morally binding civil law.

Consider the political implications of such a statement. The pope in Italy is telling us what we as North Americans can and cannot make into a law. There are commands that you can dress up in the language of law, he says, but you can’t make them binding. In case we still don’t get it, he goes on (§73):

Abortion and euthanasia are thus crimes which no human law can claim to legitimize. There is no obligation in conscience to obey such laws; instead there is a grave and clear obligation to oppose them by conscientious objection.

Americans who wish to be conservative with respect to the church, then, must be prepared to be seen as political radicals. They have to be content to make common cause with those whom the media and liberals stigmatize as “extremists” or, in another favorite expression, as “scary.”

And it is not only on the subject of human life that conservative Catholics must be prepared to be scary. In the Vatican’s recent “Considerations on Unions Between Homosexual Persons,” the Catholic Church made even stronger calls for rebellion on the part of its billion followers throughout the world. With imperturbable self-assurance it calls on Catholic politicians to oppose any same-sex legislation. They are to fight it in its conception, to vote against it, and, if it should pass into law, to oppose and obstruct its implementation. All Roman Catholics, including politicians, are called to engage in civil disobedience if necessary to lessen or thwart its effects.

Surely, then, anyone who went over to Rome in pursuit of conservatism alone would be seriously misguided. If he were consistent, he would find that the very attempt to embrace Catholicism’s religious conservatism would force upon him extremism of a political sort.

Is there some other way to become a conservative? Is there anywhere a lost lane-end into a conservative paradise with no extremist implications? If there is, I am unaware of it.

Keeping the Root

But perhaps a hopeful Protestant conservative might think there is. I have been looking for a conservative option in the wrong places, he might say. General and institutional conservatism are indeed impossible today because the social rot runs too deep. We need a new reformation. We have to cut back the foul growth upon the body politic, perhaps to the very root. But that root can be conserved and ought to be. It is the Greco/Judeo/Christian tradition itself, of which, when it is rightly understood, we have every reason to be proud. We need a reformation and a restoration of the great thing that was.

One objection to this proposal is terminological. People who want to go back to some past era and begin again are not really conservatives at all. They are reactionaries. Worse still, they are utopians. Reactionaries are utopians no less than liberals and socialists, except that their utopia is in the past. This makes them even less believable than the dreamers who look for utopia in some imaginary and vague future. Real conservatives are suspicious of the claim that there will ever be a manmade utopia. The claim that there already has been one only makes us laugh.

A second objection goes beyond terminology. Even had there been a golden age, there would be no way to get back to it from here. There are, of course, such beautiful experiments in living as that of Old Order Mennonite and Amish communities, which might almost persuade us that it is possible after all to turn back the clock.

Maybe we all could live as people did in previous centuries if we had the courage and determination of these fine people. But just as unspoiled English villages are preserved by the economic energy and tourist dollars generated in Slough, so the history of Amish and Mennonite communities shows them to survive only when embedded in economies large enough to tolerate them and strong enough to protect them in their eccentricity.

A final objection to the reactionary alternative to conservatism is that the flaws we are seeking to eradicate from contemporary society may lie so deep that they are in the root itself, rather than merely in the branches. One hesitates to give any time to this view because of its huge popularity with some of the West’s greatest numbskulls: the kind that con crystals, mumble mantras, and gabble about globalization. But even their patronage is not sufficient to discredit the idea completely. More credible voices have defended it eloquently.

Terrible Dreams

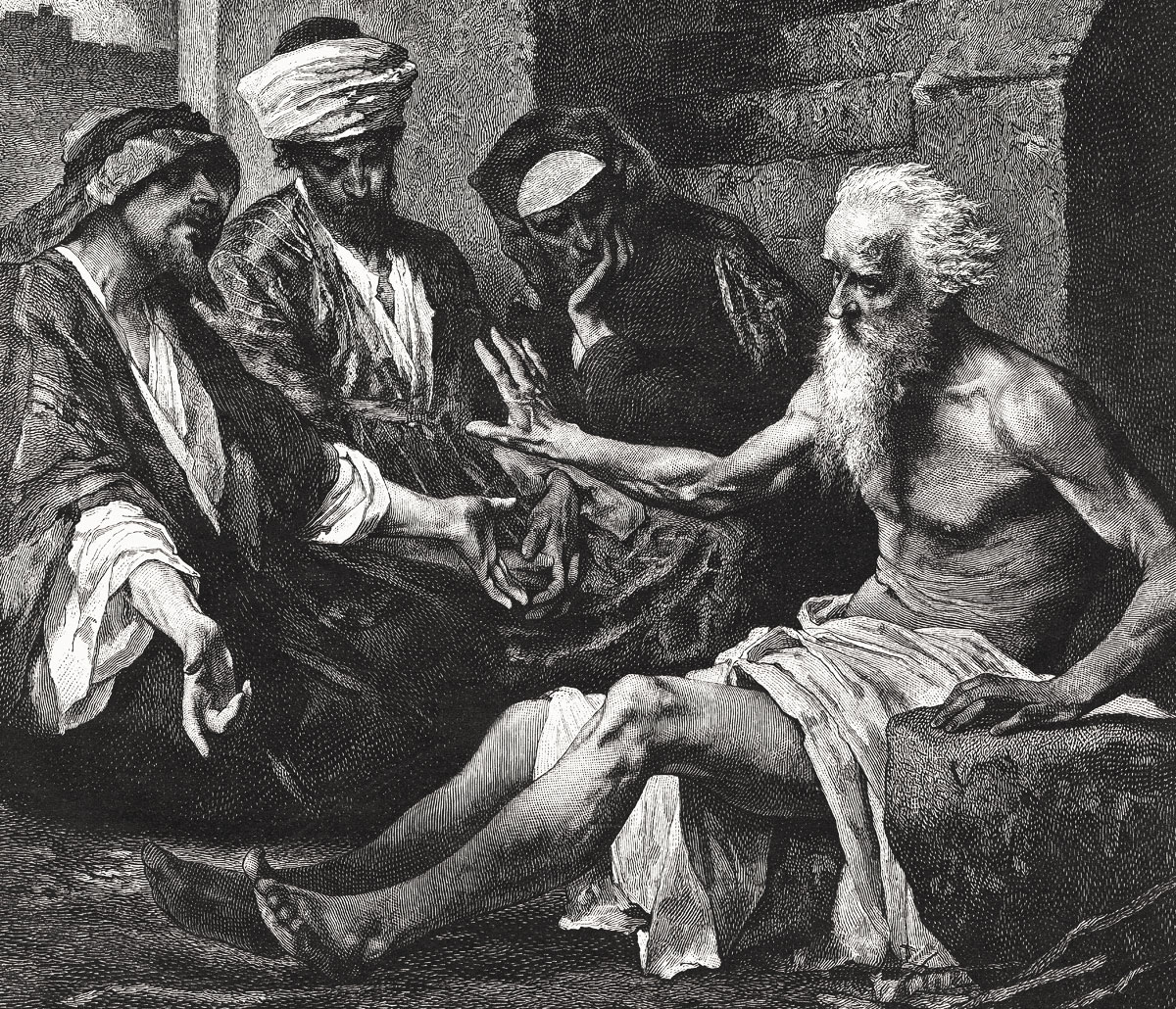

One is the Nobel Prize Laureate of 2002, Imre Kertész. I quote from his acceptance speech:

It is often said of me—some intend it as a -compliment, others as a complaint—that I write about a single subject: the Holocaust. I have no quarrel with that. . . .Which writer today is not a writer of the Holocaust? One does not have to choose the Holocaust as one’s subject to detect the broken voice that has dominated modern European art for decades. I will go so far as to say that I know of no genuine work of art that does not reflect this break. It is as if, after a night of terrible dreams, one looked around the world, defeated, helpless.

He then goes on to explain what he believes to be the meaning of the Holocaust.

I have never tried to see the complex of problems referred to as the Holocaust merely as the insolvable conflict between Germans and Jews. I never believed that it was the latest chapter in the history of Jewish suffering, which followed logically from their earlier trials and tribulations. I never saw it as a one-time aberration, a large-scale pogrom, a precondition for the creation of Israel. What I discovered in Auschwitz is the human condition, the end point of a great adventure, where the European traveler arrived after his two-thousand-year-old moral and cultural history.

Kertész’s bold proposition, that Auschwitz is the ripe fruit of Western civilization, and therefore the refutation of all the West has stood for, is certainly controversial, but not, I think, ridiculous. -Conservatives believe that ideas have consequences and that history gives concrete expression to what was first present as an idea. Therefore, it is not impossible to think that the monumentally destructive idea of Auschwitz grew in the womb of history for many centuries before being born.

But if that is so, there seems to be no historical antecedent to which the reactionary can appeal as a golden age worthy of being recovered. For even if it returned, its gold would tarnish soon enough and leaden Auschwitz would be its heir.

I think it is possible to agree with Kertész and many other postmodern critics of the West that there is something radically wrong with Western culture. But the evil at the heart of it, I would say, is not what they think. It is not racism that led to Auschwitz, or sexism, or homophobia, or even all of them combined. Like senile men and women, the critics of the West are always trying to remember what ails them and always forgetting the name.

Coetzee calls it “Disgrace”; Philip Roth recently came nearer the mark with his fine title, “The Human Stain”; Immanuel Kant referred to it centuries ago as “humanity’s bent stick” out of which, he said, no straight thing could be made. Kertész himself hints that it may be “the human condition.” But Christians have always called it by its real name: Original Sin. And it is not peculiar to Western society, but universal.

Warped by Sin

The doctrine of Original Sin teaches that human nature and the human environment have been warped by sin, so that the very instruments by which we try to cure ourselves are always infected with the same disease. We can never entirely escape the effects of sin while life lasts, and even the partial immunity to them that we can obtain is only available through repentance and by divine grace.

It is because the original conservatives, men like Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre, had such a vivid awareness of Original Sin that conservatism has never been utopian in its outlook. No straight thing can be assembled piecemeal out of institutions, or woven into (or out of) the whole social fabric, or discovered serendipitously as the preserved remnant of some golden age. It is the waning recognition of Original Sin that explains (though it does not justify) the extremist conservatism of a John Betjeman, the irrational desire to blow up in order to conserve.

“Can you be a conservative today (even if you want to)?” I don’t think so. You may, of course, be saddled with a conservative temperament, as I am, but it will require large doses of self-deception to find an object already in existence and worthy of being maintained in existence. We need to recover instead an older picture of life, which existed before the advent of the modern age, before Burke and de Maistre, and therefore before conservatism itself.

According to this nearly forgotten account, men and women are pilgrims and sojourners, not much concerned with the upkeep of the inn in which they happen to be passing life’s strange night, for they are seeking another city, whose builder and maker is God. •

The Providential Monk

One of my socialist friends at school calls me a conservative anarchist, and it does make a certain sense. But I think you can be a conservative even in a world of Sloughs, by keeping your heart and mind fixed upon the providence of God.

When Benedict wrote his Rule (one of the great conservative documents of all time), the Roman virtues had all but passed from memory. But they hadn’t passed completely from memory—and Benedict resurrected that ancient office of the paterfamilias and baptized it in his description of an abbot’s fatherly duties. I do not think he was trying to revive the past; rather, he was retrieving something genuinely good from the past and refashioning it for the present, looking forward always to the Second Coming of Christ.

So maybe the conservative does not want to conserve Slough, but even in Slough there are cracks in the asphalt and rhubarb shooting through; maybe dim memories of an age in which the words “ manliness” and “heroism” and “duty” and “grace” meant something. To try to keep these memories alive—to adapt them to the circumstances in which we find ourselves—might be a fit object for the conservative.

I teach literature that used to be the assumed patrimony of everyone who was literate and now is hardly readable by graduate students. Can’t I be a monk, preserving some love for that literature and some knowledge, for a better day? That is not utopian, but providentialist. And it is unfair to call it “piecemeal.” A man can only do what a man can do. I cannot turn I-95 into a village street. But I can chuck the TV out the window and read in the evening.

Graeme Hunter is a contributing editor to Touchstone and Research Professor of Philosophy at Dominican University College in Ottawa. He is the author of Radical Protestantism in Spinoza's Thought (Ashgate).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor