To Strut & Fret an Hour Upon the Stage

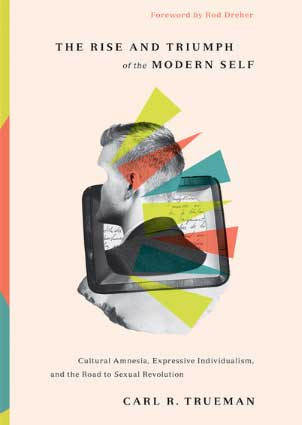

The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to Sexual Revolution by Carl R. Trueman

In The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self: Cultural Amnesia, Expressive Individualism, and the Road to Sexual Revolution, Carl Trueman, professor of history at Grove City College, has written what I call a "mountaintop work." I refer not just to its intelligence and breadth of learning, but to how it works in the mind of the reader. Like Joseph Pieper's Leisure: The Basis of Culture, C. S. Lewis's The Abolition of Man, and Christopher Lasch's Culture of Narcissism, this work takes you to the summit of a great height, from whose vantage the many wandering roads, woods, streams, farms, and hills below, a seeming confusion of the arbitrary and happenstance, resolve themselves into order, so that you see not only what your guide points out to you, but plenty of other things as well, and not individually, but in all their many and often unexpected relationships. It reveals a world—or in this case, an anti-world.

Trueman's thesis, if I may be permitted an utterly inadequate condensation, is that contemporary man is a "self," whose existence is self-fashioned, not given by nature or culture or God, a self that acts upon the inert and otherwise meaningless stuff of the body, just as our sophisticated tools act upon the inert and meaningless stuff of what used to be called creation. Such a self therefore requires, as an inherent right, as an affirmation of its dignity, the stage of its choosing, whereupon to display itself. We are all peacocks now, I might jest, except that that does an injustice to the worthy peacock, who spreads his many-eyed plumes to the sun for the most earthy and natural of reasons, to win the heart of the peahen, that there should be more peafowl in the world. Better said, perhaps: we are all hypocrites now, letting everyone know what our right hand and left hand and other members farther south are doing, because if we fail to make that display, we cease

to be.

Tools of Our Tools

The malady is of no recent date, as Trueman shows. We have been nailing up the stage, as he sees it, at least since Rousseau, Blake, Wordsworth, and Shelley. But why not since man first strutted upon the earth? Here Trueman, building upon the work of Charles Taylor and Philip Rieff, draws a distinction between the play that echoes, by mimesis, a nature that is stable and given and beheld more or less with gratitude, and the play that denies that there is any such nature, but makes itself: poiesis.

"Art is but Nature to advantage dressed," says Pope, and he is talking not about daffodils, but about us, for "the proper study of mankind is man." "The purpose of playing," says Hamlet to the actors who have come to Elsinore, "is to hold, as 'twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure" (Hamlet, III.ii). Hamlet assumes that there is such a thing as virtue, that it does not change, and that it is the duty of the artist to portray virtue's lineaments faithfully and potently.

His advice might well have been uttered sixteen hundred years before him, by Horace for example, whose Ars Poetica begins with satirical remarks on what is not good poetry, namely, what violates the nature of things, as if "snakes could be the twins of birds, or sheep the twins of tigers." Philip Sidney goes farther, saying in his Defense of Poesy that although nature gave us a Cyrus, Xenophon in his art that built upon nature "bestow[ed] a Cyrus upon the world to make many Cyruses, if they will learn aright why and how that maker made him." We read about the poetically heightened Cyrus in order to engage in mimesis of our own, imitating his wisdom and public-minded virtue.

You will notice that nowhere do Horace, Sidney, Shakespeare, or Pope locate poetry in their subjective feelings. It is most true that poetry stirs the passions, as Sidney freely affirms; indeed it is meant to do that, and thus it is more effectual than moral philosophy, which can tell you what the right thing to do is, but has not the imaginative power to rouse you to do it. But that poetry, or any other human activity for that matter, should essentially be about the making and displaying of your own feelings, thereby to become a person in full, neither Sidney nor the oft-misread Shakespeare of the sonnets could believe for a moment.

Yet, as Trueman shows, that is what we all now take for granted, even Christians. We are thus all the inheritors of ugly brothers of one birth: the cold, mechanistic, and ultimately utilitarian rationalism of the Enlightenment, and the apparent rebellion of the Romantics. Science—reduced to what can be measured and manipulated—gives us the only truth, except that which we feel "authentically" from within us, about which neither physics nor biology, neither anthropology nor moral philosophy nor theology, can have anything to say. We are slaves to those natural sciences, because we do not affirm truths that they cannot reach, truths that are infinitely more important to our lives than is the chemical composition of ice; our false revenge upon those sciences is that we employ them, technologically, to help us fashion the selves we please. We are tools of our tools both ways.

The Sempiternal Orgiast

Given those assumptions, the sexual revolution was entirely foreseeable. For sex, more than any other feature of human existence, binds the physical to the social, the personal to the cultural; and sexual congress is the prime act whose meaning reaches far into both past and future. The child is born into this family, with these ancestors and these brothers and sisters and cousins, in this country, speaking this language; and he or she will likely marry in turn and perpetuate the line.

In this immemorial view of things, as natural to man as is breathing the air, you do not choose to become a son, or an American; you are born so, and your duty is to fulfill the nature you are given, a nature at once bodily and social. There is no felt conflict between nature and nurture, since man by nature is social to the core; it is in his nature to live in the kinds of societies we find everywhere, with variations dependent upon climate, agriculture, and technological and intellectual development. The father in his study in Paris can understand the father in his tepee on the American plains. The Chinese boy who pays court to the Chinese girl by boasting about his courage can understand the romances of Chrétien de Troyes, half a world away and eight centuries before. A mother with a small child can go anywhere in the world and be met with the smiles of old women, who will offer a bite to eat and something to drink before she thinks to ask.

But, says Trueman, since the Romantic age, and since the deadly attacks, mounted by Darwin, Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud, on a settled and life-affirming nature, all that I have said will be dismissed as artifice and stricture. To be a self means to be liberated. What from? "The happiest person," says Trueman in his discussion of Freud, "is the sempiternal orgiast," because "to be satisfied is to be sexually fulfilled here and now." Hence has contemporary education become "preoccupied with the liberation of children's sexual instincts and the elimination of any religious influence whatsoever."

Sex is the central locus of a more general falsehood, that which self-styled conservatives as well as self-styled liberals appear to accept, for each is an instance of "psychological man," "a figure whose very psychological essence means that he can (or at least he thinks he can) make and remake personal identity at will." Alas, where does his self-fashioning leave him, really? Aimless, chaotic, vulnerable to the shifts and changes of social fads, which he is constantly buying and consuming. He makes of himself a billboard, lest he cease to be

at all.

Mere Effusions of Sentiment

Some of Trueman's villains had filthy minds indeed; Wilhelm Reich, for example, whom he cites to this effect: "Every moral regulation is in itself sex-negating, and all compulsory morality is life-negating." A Satanic lie, but one that we accept implicitly when we use the principle of obvious harm to specific others as the only determinant for what we should proscribe either by law or by custom. To the classic mind, to Confucius as well as to Thomas Aquinas, the moral law is for human thriving, just as healthy bones and blood and muscles and organs are for walking, running, climbing, and doing all the fine things that ordinary human beings do.

Aquinas may say, in the order of argument, that an appeal to authority is the weakest of supports, but in the order of persuasion it is not so, and he himself gratefully appeals to authority all the time. Tu se' lo mio maestro e 'l mio autore, cries Dante to Virgil—you are my teacher, my authority! To say that each man must be his own authority is to say that there shall be no more Dante, no more Aquinas. Surely that is one powerful reason why intellectual, artistic, and social creation in our time is so poor, so meager.

The abrogation of authority implies the abrogation of standards. Instead of remembering what Shakespeare says, we slander it, or forget it. Trueman cites Rieff to that effect: "the coming barbarism, much of it here and now, not least to be found among our most cultivated classes, is our ruthless forgetting of the authority of the past" (from My Life Among the Deathworks).

People are not by nature inclined to despise their forebears. They must be taught to do so. That, as Trueman shows, explains "the transformation of the humanities into disciplines by which the past is not so much examined as a source of wisdom but rejected as a tale of oppression." Why, then, emulate the virtuosity of Mozart, or Keats, or Bernini, when to do so is to re-enter that oppressive tale? It is, after all, hardly therapeutic to the self to be told that you do not know how to cast a human face, that you have no ear for complex harmonies, and that even if you put your brains on the rack and stretched them to a perfect agony, you still would not be able to write a single line as good as "Silent, upon a peak in Darien."

It is instructive, Trueman says, that having rejected or forgotten the foundation of nature, we should assume that all arguments about good and evil are mere effusions of sentiment, a hiss or a hurrah as the case may be. Justice Anthony Kennedy, in the notorious Obergefell v. Hodges case regarding same-sex pseudogamous unions, simply assumed that opponents were motivated by unconstitutional animus, a claim, says Trueman, that "denies that there is any rational basis for defining marriage as between one man and one woman." Opponents have made quite a few arguments based upon human nature, reason, and the common good, but Kennedy could not hear them, because what Trueman calls "emotivism" rules the day. The majority's opinion, "that the right to personal choice in marriage is inherent in the concept of individual autonomy, represents the triumph of expressive individualism in society." Hence, those who demand a "right" to define as marriage what they please for self-display will feel it as a personal and lethal attack if you deny the definition.

It follows, too, since nothing is merely given as a universal human reality, that there is no realm for the pre-political, no haven against the heat and the mire of political passion. Every man's home is his castle, the old saying goes, but mass media, mass schooling, and the sexual revolution in all its panoply have battered in the walls of that castle, and even children are enlisted in the war against their own

humanity.

Obvious but Unaskable Questions

Trueman's observations help me answer a question I have asked myself, a question about questions. Take, for one example, the presence of women in combat, or indeed in the military generally. The sole question to be asked is one that you are not permitted to ask at all. If I have flat feet, a rather minor skeletal disorder, the army will not accept me. But what if I have angular knees, narrow shoulders, half the muscle of a normal man, a small heart and therefore comparatively poor oxy-genation of the blood, and monthly troubles that make it dangerous for me to be in septic conditions? It is obvious that such a person has no business in a platoon.

The obvious question is, "Will this person's presence, along with the presence of similar people, actually promote rather than hinder the work and the health of the armed forces, to win battles and wars swiftly and decisively, with the least cost to life or limb?" It is a pragmatic question, to be sure, and not even the most important question, which would bring into play the right and changeless relation between man and woman. Still, it has considerable force, and it does touch upon masculine nature and the bonds of brotherhood that sexual competition can fray or break, or prevent from developing at all.

Yet that question may not be asked. It is assumed that women have a right to the stage upon which to display their military selves. We fight not for America, but for the great theater of self-expression. Quite aside from the example set by Jesus and the clear words of Saint Paul, in the matter of Christian priestesses we are not permitted to ask, "Does this innovation actually work, to fill churches, to bring people to Christ?" It is assumed that women have a right to the stage upon which to display their sacerdotal selves. We preach not Christ, and him crucified, but the blessedness of the self, so long as the self has the most current social opinions, which serve to erect pretty stages for other selves.

Diagnosis & Warning

We see, then, that more than sexual morality is at stake. Again and again, Trueman is at pains to remind us that we have accepted incomplete or incorrect notions of what it is to be a human being. I shall end with a sentence by Trueman that is both diagnosis and grave warning: "The world of psychological man is a world in which, to borrow Marx's phrase, all that is solid is constantly in danger of melting into air—including our selves."

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

31.5—September/October 2018

Errands into the Moral Wilderness

Forms of Christian Family Witness & Renewal by Allan C. Carlson

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor