Owning Slavery

A Christian Response to "The Case for Reparations"

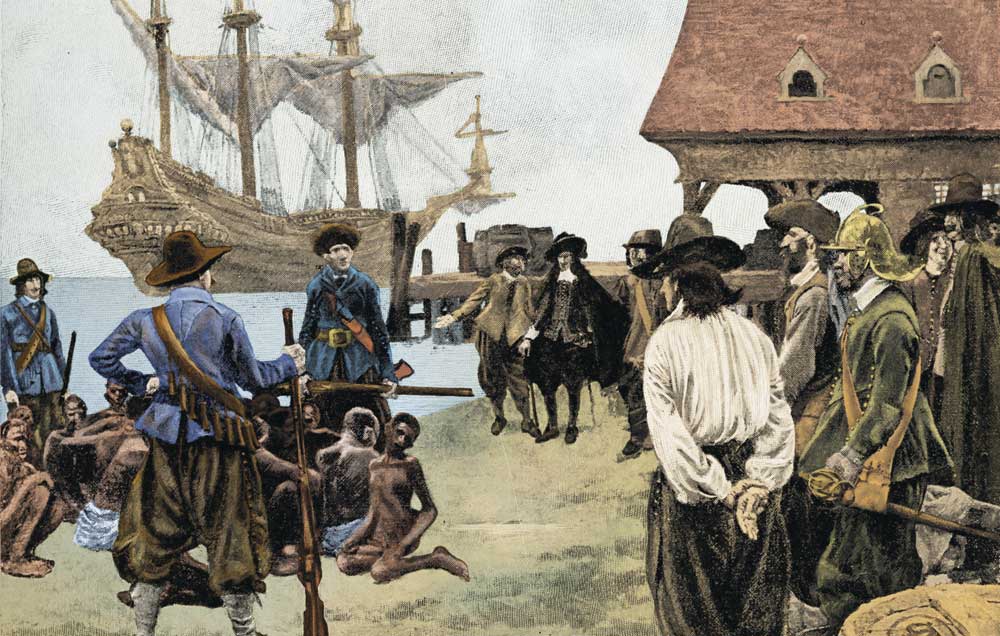

Ta-Nehisi Coates's essay, "The Case for Reparations" (Atlantic Monthly, June 2014) brought a great deal of attention to a proposal that has simmered in the background of American political discourse for several decades. It is not unreasonable to surmise that the "1619 Project" of the New York Times Magazine, announced in October 2019, emerged, in part at least, as a result of Coates's influential argument. The purpose of the Times project is to rewrite American history and to reconceive the nature of our country by emphasizing the central importance of slavery to the economic and political development of the United States. Sixteen-nineteen is the year that African (but not only African) slaves were first brought to the Jamestown colony in Virginia; the implication is that this is the real beginning of American history.

This notion raises serious questions of justice for all Americans, but especially for Christians. Coates's article, while often moving, is finally unpersuasive, because the logic and the history supporting his demands are both defective; but the challenge he has issued provides, nonetheless, an occasion for us to reflect upon the part that Christianity has played in the history of slavery and race relations.

A Matter of Theft

Coates's thesis is that slavery, as well as various kinds of legalized discrimination against the freed slaves and their descendants in the aftermath of the American Civil War, amounted not merely to mistreatment but to actual theft of the resources of African Americans. He maintains that every institution in the United States benefited from this theft and, therefore, that white Americans, who have all been enriched to some degree from this ill-gotten wealth, owe compensation to black Americans. Coates argues that the labor of the enslaved Africans was stolen from them, and that subsequent discrimination, even after they were freed, resulted in their impoverishment and thus is also a kind of theft.

He draws particular attention to the housing market, focusing especially on Chicago. Since most white Americans accumulated wealth by acquiring their own homes during the prosperous years following World War II, redlining and other practices that excluded blacks from the housing market prevented them from comparable wealth accumulation. And the housing situation is only one aspect of the segregation, either legal or de facto, that prevented blacks from participating fully in the economy and thus deprived them of prosperity.

It would be possible to respond by observing that inhibiting a man from gaining wealth is not exactly the same as stealing what he actually has, but this may not unreasonably be regarded as a trivial objection. Harm has certainly been done. A more substantial objection is that, over the course of American history, numerous minority groups have suffered discrimination of various kinds: Irish, Italians, Poles and other central Europeans, Jews, Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese. Most men and women in these groups have, however, succeeded in overcoming the prejudice against them and thriving to an extent comparable to what used to be the Anglo-Saxon majority.

The obvious retort to this objection is that the immigration of these peoples was voluntary; they were not brought to this country as slaves. Despite Coates's lengthy discussion of redlining and other forms of discrimination subsequent to the emancipation of the slaves, the fact of slavery, applied exclusively to black men and women in this country for more than two centuries, must be the core of any case for reparations.

But "The Case for Reparations" provides no historical context for slavery and, indeed, hardly treats slavery at all. The heart of the essay and its most powerful impact emerge from the presentation of numerous examples of racially motivated mistreatment of African Americans during the earlier part of the twentieth century.

Coates does mention a woman who was kidnapped as a girl from what is now Ghana and brought to the United States as a slave, but he does not say by whom she was seized and sold into slavery. In fact, Coates makes no further reference to how black Africans were enslaved in the first place and how they fell into European hands. So far as I can determine, most contemporary university students think that the institution was invented by the British and Americans, who captured black Africans in their own country and brought them to North America beginning in the seventeenth century. Nothing in Coates's influential essay would disabuse them of this illusion.

A Fanciful Etymology

R. V. Young is Professor of English Emeritus at North Carolina State University, a former editor of Modern Age: A Quarterly Review, and the author of Shakespeare and the Idea of Western Civilization (Catholic University of America Press, 2022). He and his wife are parishioners at St. Ignatius of Antioch Church in Tarpon Springs, Florida. They have five grown children, fifteen grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on history from the online archives

15.6—July/August 2002

Things Hidden Since the Beginning of the World

The Shape of Divine Providence & Human History by James Hitchcock

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor