Owning Slavery

A Christian Response to "The Case for Reparations"

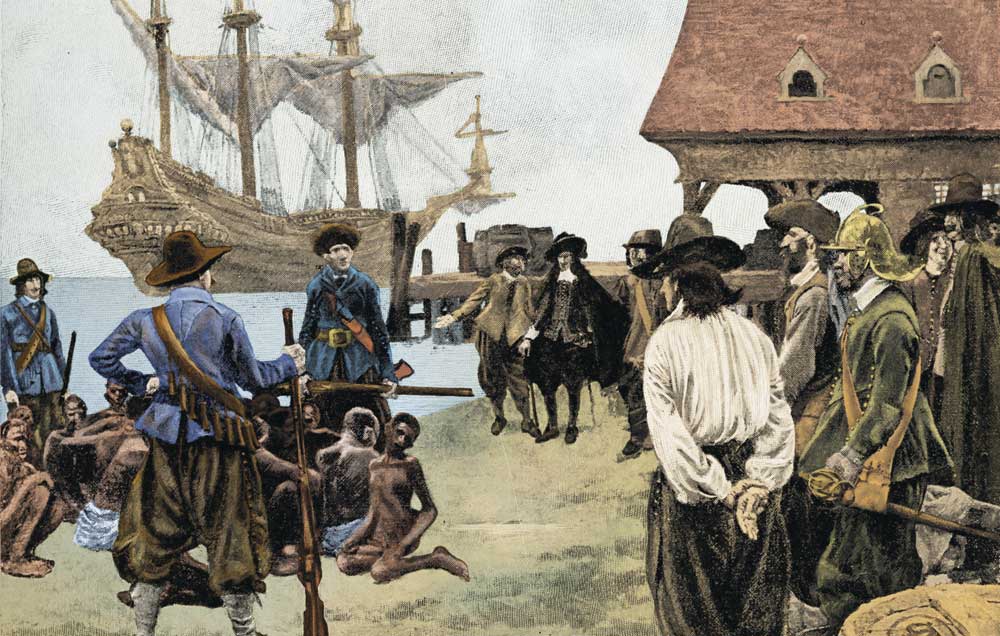

Ta-Nehisi Coates's essay, "The Case for Reparations" (Atlantic Monthly, June 2014) brought a great deal of attention to a proposal that has simmered in the background of American political discourse for several decades. It is not unreasonable to surmise that the "1619 Project" of the New York Times Magazine, announced in October 2019, emerged, in part at least, as a result of Coates's influential argument. The purpose of the Times project is to rewrite American history and to reconceive the nature of our country by emphasizing the central importance of slavery to the economic and political development of the United States. Sixteen-nineteen is the year that African (but not only African) slaves were first brought to the Jamestown colony in Virginia; the implication is that this is the real beginning of American history.

This notion raises serious questions of justice for all Americans, but especially for Christians. Coates's article, while often moving, is finally unpersuasive, because the logic and the history supporting his demands are both defective; but the challenge he has issued provides, nonetheless, an occasion for us to reflect upon the part that Christianity has played in the history of slavery and race relations.

A Matter of Theft

Coates's thesis is that slavery, as well as various kinds of legalized discrimination against the freed slaves and their descendants in the aftermath of the American Civil War, amounted not merely to mistreatment but to actual theft of the resources of African Americans. He maintains that every institution in the United States benefited from this theft and, therefore, that white Americans, who have all been enriched to some degree from this ill-gotten wealth, owe compensation to black Americans. Coates argues that the labor of the enslaved Africans was stolen from them, and that subsequent discrimination, even after they were freed, resulted in their impoverishment and thus is also a kind of theft.

He draws particular attention to the housing market, focusing especially on Chicago. Since most white Americans accumulated wealth by acquiring their own homes during the prosperous years following World War II, redlining and other practices that excluded blacks from the housing market prevented them from comparable wealth accumulation. And the housing situation is only one aspect of the segregation, either legal or de facto, that prevented blacks from participating fully in the economy and thus deprived them of prosperity.

It would be possible to respond by observing that inhibiting a man from gaining wealth is not exactly the same as stealing what he actually has, but this may not unreasonably be regarded as a trivial objection. Harm has certainly been done. A more substantial objection is that, over the course of American history, numerous minority groups have suffered discrimination of various kinds: Irish, Italians, Poles and other central Europeans, Jews, Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese. Most men and women in these groups have, however, succeeded in overcoming the prejudice against them and thriving to an extent comparable to what used to be the Anglo-Saxon majority.

The obvious retort to this objection is that the immigration of these peoples was voluntary; they were not brought to this country as slaves. Despite Coates's lengthy discussion of redlining and other forms of discrimination subsequent to the emancipation of the slaves, the fact of slavery, applied exclusively to black men and women in this country for more than two centuries, must be the core of any case for reparations.

But "The Case for Reparations" provides no historical context for slavery and, indeed, hardly treats slavery at all. The heart of the essay and its most powerful impact emerge from the presentation of numerous examples of racially motivated mistreatment of African Americans during the earlier part of the twentieth century.

Coates does mention a woman who was kidnapped as a girl from what is now Ghana and brought to the United States as a slave, but he does not say by whom she was seized and sold into slavery. In fact, Coates makes no further reference to how black Africans were enslaved in the first place and how they fell into European hands. So far as I can determine, most contemporary university students think that the institution was invented by the British and Americans, who captured black Africans in their own country and brought them to North America beginning in the seventeenth century. Nothing in Coates's influential essay would disabuse them of this illusion.

A Fanciful Etymology

The mischief caused by treating slavery in the American colonies and, subsequently, in the United States as if it occurred in a vacuum can be gauged by considering two articles that I happened upon late in the summer of 2018. The August 29, 2018 issue of the New York Times includes an opinion piece by Ria Tabacco Mar entitled "Why Are Black People Still Punished for Their Hair?" In the course of denouncing the "bias against natural black hair," the author asserts that employers ought not to have "free rein to discriminate against workers who wear dreadlocks, a hairstyle said to be named by slave traders who viewed African hair texture as 'dreadful.'" In the electronic version of the article, a link takes you to a footnote in an amicus curiae brief, dated November 10, 2016, which provides the same etymology for "dreadlocks."

No evidence is cited for this explanation of the word, because none exists. Any experienced writer or editor ought to be immediately suspicious of such a simplistic etymology, and it is a not unreasonable assumption that the editorial staff of the New York Times would have access to the online version of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Had one of their editors bothered to check it, he would have found that the OED's earliest citation of the term "dreadlocks" dates from 1960 and was associated with the Jamaican Rastafarian cult, whose members modeled their hair on images of Ethiopian warriors. Further, this etymology suggests that the purpose of the hairstyle was just what anyone would assume: to inspire fear in those whom the Rastafarians regarded as enemies. Whatever the intention of those who wear dreadlocks nowadays, the motive of the Rastafarians who introduced the hairstyle and the term to the contemporary world was provocative, not to say, belligerent.

The notion that "dreadlocks" derives from the distaste of slave-driving whites for what they regarded as an ugly way of arranging hair is plainly a bit of wishful thinking on the part of progressive activists. That such an obvious error should find its way into an op-ed in the New York Times as well as a judicial brief inspires confidence in neither our journalism nor our jurisprudence. This is more than a trivial error in philology: it illustrates how a display of spurious learning or expertise may be deployed to obscure any aspect of reality that undermines the preferred progressive "narrative."

About a week after reading this piece in the Kindle edition of the New York Times, I received the print edition of the Times [of London] Literary Supplement for August 24, 2018, where I read another article with a more complex vision of slavery, Colin Grant's "Words from the Sold: Listening to the Last Survivor of the Atlantic Slave Trade," a discussion of Zora Neale Hurston's interview with Oluale Kossola (renamed Cudjo Lewis by his white owner) in Barracoon. Hurston provides a salutary example of a woman who could be indignant about the baneful legacy of slavery without losing perspective. Although "Hurston's larger purpose," writes Grant, "was to challenge the prejudices of white America," she was, nonetheless, "shocked by the depth of African complicity in Kossola's tale":

"My people had sold me and the white people had bought me," writes Hurston. "That did away with the folklore that I had been brought up on—that the white people had gone to Africa, waved a red handkerchief at the Africans and lured them aboard the ship and sailed away."

As a little girl, Zora Neale Hurston believed in what she recognized, as an adult, as "folklore." That was in 1927. In 2018 (coincidentally, the year in which the full text of Barracoon was finally published), the New York Times, our "paper of record," published an essay that took seriously an equally childish piece of folklore, a fanciful etymology of "dreadlocks." These contrasting examples of candor and disingenuousness on the subject of slavery and race highlight what is usually missing in discussions of the demand by black activists and their white supporters for reparations for the enslavement of men and women of African descent in this country: an informed account of the history of slavery in general and in Africa specifically.

A Routine Matter

The transatlantic slave trade, while unique in some of its features, was hardly unprecedented. Slavery and the trade in slaves had been pervasive throughout the civilized world for millennia. Europeans and Asians, as well as Africans, had been enslaved and sold as slaves as far back as historical records exist. Before the first Portuguese trader set foot on the shores of West Africa late in the fifteenth century, powerful kingdoms in sub-Saharan Africa were enslaving their conquered enemies and selling them to buyers in the north of Africa, in Asia Minor, in India, and on the coastal lands of eastern Mediterranean Europe.

Classical Greeks and Romans, as well as the Egyptians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Hittites, and all the rest, took slavery for granted. It comes up as a routine matter in the Histories of Herodotus, for example, among both the Greeks and the "barbarian" Persians and Medes. Aristotle is often condemned by sanctimonious critics of our time for justifying slavery in the first book of the Politics (1253b–1255b), when he was merely offering a rational explanation of what, along with the overwhelming majority of his contemporaries, he regarded as a natural fact. This is understandable, since slavery was woven into the very fabric of the ancient world.

We ought not to minimize the opprobriousness of the institution despite its pervasiveness. Consider the insight provided by one of Ovid's elegies, in which the poetic persona is both teasing his mistress Corinna and sympathizing with her after her hair has all fallen out because of an attempt to dye it. I warned you this would happen, he says. And why did you have to change it anyway? It was so beautiful, so fine and silky and easy to arrange that you never suffered pain from your hair being tangled in the comb and yanked:

The handmaid's body was always safe;

often I saw her dress your hair, and never

did you snatch her arms to wound them with a hairpin. (Amores I.xiv.16–18)

The good news, Ovid's speaker assures Corinna, is that her hair will grow back, and in the meantime, "For now Germany will send you seized locks; / you will be saved by the offering of a subdued race" (ibid., 45–46).

In other words, the slave girl who set Corinna's hair was lucky that her mistress had no occasion to stab her with a hairpin, and Corinna could take solace in the exploitation of German slave women by their masters, who shaved their heads and sold their hair as wigs for fashionable Roman women. The purpose of Roman slaves is, clearly, the "bodily service" (somati boetheia) described by Aristotle (1254b).

If poetry is too fanciful for you, consider the information offered by a purely pragmatic work, the Periplus Maris Erythraei, a handbook for traders in luxury goods on the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, dating from a.d. 40–70, probably written by a Greek-speaking Egyptian. Malaô, a port in what is now northern Somalia, provided, along with such things as myrrh, incense, and cassia, "occasionally slaves" (somata spanios) for Arabia. Note that here, as in various other places in the Periplus, the word for "slaves" literally means "bodies." This usage also occurs once in the New Testament (Rev. 18:13), as well as in the Septuagint and throughout classical Greek literature.

Another port in the Horn of Africa, Opônê, furnishes, along with cassia and tortoise shell, "better-quality slaves" (doulika chreissona) for Egypt. The port of Barygaza, on the northwest coast of India, furnished various Indian goods in exchange not only for "precious silverware" and "fine wine," but also for "slave musicians and beautiful girls for concubinage" (mousicha kai parthenoi eueideis). The Periplus author does not identify the origin of the slaves, but he does mention a "vicious" people of the southern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, who enslave anyone they save from shipwreck.

This is in the first century of the Christian era; Lionel Casson, editor and translator of the Periplus, reminds us that the second-century b.c. Greek adventurer Eudoxus "took along a supply of young slave musicians" on a journey to India. Casson cites further evidence of the importation of Western slaves not only into India, but even as far as China.

Ibn Battuta's Witness

The rapid expansion of Islam beginning in the middle of the seventh century a.d. was accompanied by an expansion of the slave trade. For instance, as documented in The East African Slave Trade: The History and Legacy of the Arab Slave Trade and the Indian Ocean Slave Trade (Charles River Editors, cited hereafter as East), there are contemporary records of "the Zanj Rebellion, a slave uprising that took place between 869 and 883," which "began not far from the present-day city of Basra in modern Iraq." The word "Zanj" was a general umbrella term used by Arabs to define the black African or Bantu races of Africa that comprised "by far the greatest number of slaves present in Arabia."

The trade in slaves across the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, documented by the author of the Periplus in ancient times, continued into the Middle Ages and beyond. In the tenth century, the Islamic traveler and geographer Buzurg Ibn Shahriyar mentions Zanj slaves bound for Arabia from the coast south of Somalia, and the famed fourteenth-century Islamic traveler Ibn Battuta "makes a note in 1331 of African slaves being present at the coastal trade depot of Kilwa" (East). Although the slaves were mainly destined for the Arabian Peninsula, some of them ended up as far away as India and China.

The African slave trade had thus been going on for centuries when the Portuguese became involved in the latter half of the fifteenth century, and they never succeeded in establishing their hegemony on the East African coast. "The 1606 account of Portuguese mariner Gaspar de São Bernardino . . . notes the arrival of 'Arab Moors' on regular expeditions to the islands to fill the holds of their dhows with slaves" (East).

Ibn Battuta also provides information during his travels in India regarding slave-trading in the opposite direction:

After this I proceeded to the city of Barwan, in the road to which is a high mountain, covered with snow and exceedingly cold; they call it the Hindu Kush, i.e. Hindoo-slayer, because most of the slaves brought thither from India die on account of the intenseness of the cold. (The Travels of Ibn Battuta, 1829; reprint Dover, 2004)

Battuta also mentions traveling in China with slave girls, as well as having "some slave girls and four wives" during his residence in the Maldives. He also asserts, "Female slaves are very cheap in China; because the inhabitants consider it no crime to sell their children, both male and female."

Back in Africa, Battuta journeys south of the Sahara and develops a generally negative view of the culture of black Africans. He mentions that slaves work the copper mines in Mali. Such references could be multiplied, but these ought to suffice to make the point: Ibn Battuta, the most widely traveled man of the Middle Ages—even more so than Marco Polo—witnessed slavery everywhere he went and was himself involved in it. Western Europeans joined in the trade rather late, although the rapidly developing technology and entrepreneurial efficiency of the Western world may well have worsened the conditions of slaves in some respects.

The Unique Western Record

It is obvious, then, that the Incarnation of the Second Person of the Holy Trinity as Christ Jesus and the development of the Church that he founded occurred in a world thoroughly entangled in the institution of slavery and among peoples who, however much they may have feared or loathed slavery, nonetheless accepted it as an inevitable feature of civilized life. It may well seem curious to Christians today that the New Testament has so much to say about slavery in a metaphorical sense, and so little to say about the literal institution of slavery, which it never unequivocally condemns.

Much the same may be said about the Church Fathers and medieval Scholastic theologians. Nevertheless, during the course of the Middle Ages, slavery diminished and eventually came to be negligible in the heartlands of Christendom; and, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a great movement arose among Christians in both Europe and the Americas to abolish, first, the trade in slaves and, finally, the institution of slavery itself.

The Christian culture of the West is like every other culture of the world insofar as it accepted slavery and the trade in slaves for a substantial part of its history. So far as I can determine, however, it is unique in having devised a moral case against slavery and ending it, at least as a legal institution, not only within its own borders, but throughout the world. In other words, the record of Western civilization, including the British colonies in North America that became the United States, is deplorable in its history regarding slavery—but it is better than that of anyone else.

Those who fulminate against America on account of its record on slavery must, then, in justice tell us who has done better. Against what standard is America, or Christendom as a whole, being judged?

The deep culpability of the Christian peoples of Europe and America is that they ought to have known better, certainly by the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the trans-Atlantic slave trade began in earnest. Moreover, the persistence of slavery and the slave trade into the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as Europeans and North Americans were attaining levels of personal freedom unprecedented in history, makes the lot of African slaves especially bitter.

Slavery Reimagined

It would seem to be the case that Christianity had previously prepared the way for the abolition of slavery by reshaping the image of slavery in the moral imagination of Christians and, eventually, of men and women in general, at least in the Western world. This reimagining of slavery seems to have effected a more profound and lasting change than a strictly political campaign, especially an untimely campaign, might have done; and it ultimately made possible the condemnation and abolition of slavery after many centuries of Christianity. "Slave" (doulos), "slavery" (douleia), "to enslave" (douloō), and so on appear in the New Testament more than 150 times, preponderantly in the contrast between being a "slave" of the flesh or the Law or sin or Satan, and being a "slave" of righteousness or God or Christ.

To be sure, St. Paul rather notoriously counsels slaves to remain in their state of servitude and to serve their masters faithfully and willingly (1 Cor. 7:21–22; Eph. 6:5–9; Col. 3:22–25), but he also admonishes the masters of slaves to treat them "justly and equitably," remembering their own Master in heaven (Col. 4:1; Eph. 6:9). The most important discussion in the New Testament of slavery as an institution comes, however, in St. Paul's Epistle to Philemon, in which the apostle returns to Philemon his runaway slave, Onesimus, with the injunction that the master receive the fugitive "no longer as a slave, but more than a slave, as a beloved brother, especially to me, but how much more to you, both in the flesh and in the Lord" (Phlm. 16). One might venture to say that Paul "deconstructs" the institution of slavery: he leaves it in place while transforming it from within. Philemon has his slave back, but he is no longer a slave but a brother. Paul has, presumably, baptized the man who came to the apostle to serve him in his captivity: "I beseech you for my son, whom I have begotten in my bonds" (Phlm. 10).

To enter into the Body of Christ through baptism fundamentally transforms a man: since, as children of Adam and Eve, we are all enslaved to sin, to be baptized is to be freed by and in Christ; but our freedom comes by means of serving, that is, being the slave of, our Lord and Master. In the Letter to the Colossians, St. Paul expounds the complex, not to say equivocal relationship between the obedient Christian slave and his Christian master:

Slaves, obey in everything those who are your earthly masters, not with eye service, as men-pleasers, but in singleness of heart, fearing the Lord. Whatever your task, work heartily, as serving the Lord and not men, knowing that from the Lord you will receive the inheritance as your reward; you are serving [douleuete; i.e., acting as a slave to] the Lord. (3:22–24)

The master must realize that he is no better than his slave; in fact, "his slave" is in truth the slave of Christ, insofar as he is redeemed by Christ.

The New Testament is continually marked by reminders that its setting is a society in which slavery is taken for granted. This will be clearer if we realize that in English versions of the Bible the word "servant" usually translates doulos, which might more strictly be rendered by "slave" or "bondman," since it is the opposite of eleutheros, or "freeman." This applies, for instance, to the "servants" who are sent to collect the rent in the parable of the vineyard (Matt. 21:33–41), and also to the "servants" who tell the royal official that his gravely ill son had recovered just at the time when Jesus said the boy would live (John 4:50–53). Slaves—douloi—are frequent in both our Lord's stories and the world in which he walked. But Jesus himself lays the groundwork for St. Paul's transformation of the condition of slavery by insisting that fallen men and women are all slaves until they are liberated by the Truth:

Jesus then said to the Jews who had believed in him, "If you continue in my word, you are truly my disciples, and you will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.

They answered him, "We are descendants of Abraham, and have never been in bondage to anyone [oudeni dedouleukamen]. How is it that you say, 'You will be made free'?"

Jesus answered them, "Truly, I say to you, every one who commits sin is a slave to sin [hamartian doulos]. The slave does not continue in the house forever; the son continues forever. So if the Son makes you free, you will be free indeed. (John 8:31–36)

In the Christian dispensation, the man who is free in truth, who is set free by truth, is not he who is master of other men, but he whose master, the Son of God, has set free and made of a sinner his brother, also a son in the household of God.

Not Opiate, but Spiritual Force

From a merely secular perspective, this may appear to be an evasion of the brutal fact of temporal slavery—a distracting dose of the "opiate of the people." But in the practical world of history, the Christian spiritual reimagining of slavery is the force that uniquely brought slavery to an end, at least as a legal and accepted institution, throughout the world.

By the end of the Middle Ages, slavery had substantially vanished from the heart of Western Christendom in northern and western Europe. It persisted on the margins of Europe and on the Mediterranean coast, where the Christian world was in close and contentious contact with Islam. When it re-emerged in the trans-Atlantic trade between Africa and the New World at the beginning of the Renaissance, it was British and North American Christians who eventually ended both the commerce in "bodies" and the institution of slavery itself.

To be sure, there were undoubtedly other factors at play—economic, political, philosophical—in the gradual dissolution of slavery in Europe in the course of the Middle Ages, as well as in the British and American abolition movements in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but the predominance of a vigorous Christianity is the distinctive feature of these societies in contrast to the rest of the world. It is, after all, a source of cognitive dissonance to treat your fellow redeemed sinner and brother in Christ as a piece of your property; fending off the mental and emotional strain would require recurring series of rationalizations. And, of course, in medieval Europe almost everyone was Christian.

The questioning of slavery within Christendom began with condemnations, specifically, of enslaving one's fellow Christians. In 1462, Pope Pius II, the scholarly humanist Aeneas Silvius, issued a decree against the enslavement of baptized Africans; in 1537, Pope Paul III forbade the enslavement of Indians, and subsequently, "he proclaimed the complete abolition of slavery" (Hugh Thomas, The Slave Trade, 1997). Subsequent popes condemned slavery again and again in 1639, in 1741, in 1815, in 1839, and finally, in 1888, when Pope Leo XIII commanded the Brazilian bishops to end the remnants of slavery in their country. These adjurations were largely ineffectual even in Catholic countries before the nineteenth century, when the English campaign to end the slave trade, led by William Wilberforce, was backed up by the British Navy, and the American abolitionists had their will enforced by Abraham Lincoln and the Union Army.

Slavery for Sugar

Hugh Thomas suggests that the glamorization of classical antiquity by Renaissance humanists provided a cultural atmosphere in which a resurgence of slavery, which had largely vanished from most of European Christendom, seemed desirable and plausible—at least insofar as it involved African slaves in the New World. But the emergence of a craving for sugar among Europeans and, later, their North American cousins provides a more plausible explanation for the massive expansion of the African slave trade and its persistence into the nineteenth century.

"Western Europe and, to a lesser extent, North America were in the seventeenth century for the first time experiencing the charms of this product on a grand scale," Thomas writes in The Slave Trade. "It was not only the classic beverages [tea, milk, coffee] which gave sugar its frame: rum had a wonderful history of success in Britain; so did jam." The greater part of the slaves whom the British brought to America worked on sugar plantations by the end of the seventeenth century; by the 1770s, the figure was two-thirds.

What incalculable mischief has been caused by addictions to refined white crystals! And what a sobering testimony to the pernicious selfishness and greed of fallen men that they would reduce their fellow men to miserable servitude on account of a craving for sweets!

There is, certainly, plenty of guilt to go around among the Europeans and European colonists in the Americas who traded in slaves and transported them under horrific conditions across the Atlantic Ocean. To offer a particular instance, Thomas quotes William Pitt the Younger, speaking to the House of Commons in 1792: "No nation in Europe . . . has fallen . . . so deeply into this guilt as Great Britain." Thomas proceeds to list prominent investors in the South Sea Company—which was formed principally to carry slaves to the Spanish empire—ranging from Queen Anne and her royal successors to "smaller stockholders [who] included Swift, Defoe, Sir Godfrey Kneller (the portraitist of all his fellow investors), and Sir Isaac Newton."

The leading lights of the French Enlightenment were generally opposed to slavery, including Voltaire, who ridiculed the slave traders in various works. But, as Thomas notes, Voltaire's record is hardly unambiguous:

He also criticized slavery in his Dictionnaire philosophique in 1764, in a rather indirect manner, and argued that "people who traffic in their own children are more condemnable than the buyer; this traffic shows our superiority." Not surprisingly, in view of that remark, he seems to have gambled in the slave trade himself. He accepted delightedly when the leading négrier of Nantes, Jean-Gabriel Montaudoin, offered to name one of his ships after him.

The Tribes' Complicity

The disparagement of Africans who sold their fellow Africans is not altogether fair; for centuries, Europeans had recognized that they were all part of Christendom. "Africa," however, was a European invention: the denizens of sub-Saharan Africa thought of themselves as members of various tribes and kingdoms, not as "Africans."

The fact remains, nevertheless, that the African slave trade—both trans-Atlantic and the trans-Saharan that preceded it—would have been impossible without the complicity of these various kingdoms and tribes. Commerce in slaves in black Africa was well established long before the Europeans arrived, and would continue after they had ended it in their own domains. Until the latter half of the sixteenth century, as Hugh Thomas observes, "the traffic in African slaves to Europe, or the Indies, was small in comparison with the ever-flourishing trade across the Sahara."

The first European slave traders, the Portuguese, quickly learned that it was safer and more profitable to deal with local African rulers and merchants than to undertake for themselves the capture of slaves, and their rivals and successors from other European nations quickly learned the same lesson. While it is true that the Atlantic slave trade increased warfare among African tribes and kingdoms, which would sell captured enemies as slaves, as Thomas points out, "wars were frequent before the Europeans arrived in West Africa, and were probably sometimes undertaken to obtain slaves even then."

A Resilient Institution

The campaign of abolition from the late eighteenth century until the end of the nineteenth confirms the resiliency of slavery, in the human heart as well as in the world, manifest in the institution's long history. Thomas relates that when a community of freed slaves in West Africa, founded by the British abolitionist Granville Sharp, very quickly began to fall apart, "settlers deserted and, worst of all, some went to work for nearby slave dealers. . . . Even Henry Demane, whom Sharp had rescued from slavery by sending a writ of habeas corpus to a vessel already under sail from Portsmouth to Jamaica, became a dealer in slaves."

The African kings and chiefs who sold slaves to the European and American traders complained about the end of their lucrative business. They threatened to kill their captives if they were unable to sell them, and often followed through on the threat.

An ironically poignant episode involves the anti-slavery work of Dr. David Livingston in Zambezi. A missionary expedition led by Livingston almost by chance freed a group of 200 slaves of the Mang'anja people from the hands of the dominant Yao. The white missionaries were drawn reluctantly into the ensuing conflict between the two tribes, resulting in the overrunning of a Yao slave camp and the freeing of several hundred more slaves. Although they had been caring for the Mang'anja freedmen, the additional burden of these new dependents was beyond the missionaries' capacity, and the newly liberated slaves were left to their own devices. "The Mang'anja chiefs, however, suffering no moral indecision, seized the opportunity and took possession of the captives as the booty of war."

The editors of The East African Slave Trade, from which I have taken this incident, offer a plaintive reflection:

The moral of the story, therefore, is simply that uninformed action, based on principles of humanity, perceived to be universal, can and often will, be usurped by the practicalities of greed, power, and politics. The missionaries had entered the country of their own accord, and with superior weapons and an attitude of moral superiority, had acted in such a manner as not only to implicate themselves in a crisis, but to amplify that crisis beyond their capacity to control it.

This is an observation pertinent to the subject of reparations for slavery in America.

Prices Already Paid

Men and women of African descent were discriminated against and treated unjustly both in the thirteen original colonies and in the United States that emerged from the War of Independence against Great Britain. Africans were brought to these shores as slaves and, even after the Emancipation Proclamation, were subject to legally enforced prejudicial treatment until the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and the Civil Rights Act (1964). They deserve vindication. Someone ought to pay.

So the argument goes. As we have already observed, however, there is nothing surprising about minority ethnic, racial, and linguistic groups suffering various kinds of discrimination, both vicious and inadvertent, at the hands of the majority. Likewise, slavery—as we have maintained at length—is hardly unique. What is unique is the gradual diminution of slavery in Christian Europe and the emergence toward the end of the eighteenth century of a movement to abolish slavery—ultimately successful—in Great Britain and the United States.

It is probably no coincidence that the abolitionists arose in these countries, which had become so deeply involved with slavery: the former came to dominate the Atlantic slave trade in the eighteenth century, and, of course, slavery persisted longer in the American South than in any other Western nation. Hence, a sense of remorse has already provoked voluntary restitution. Hugh Thomas reminds us that the British West Africa Squadron in the course of 60 years freed about 160,000 slaves. He adds:

Perhaps another 800,000 additional slaves would have been shipped, if there had been no Africa squadron. Many British seamen died (1,338 in all, between 1825 and 1845) as a result of skirmishes at sea or, even worse, yellow fever and malaria on land or in the rivers of the slave coast still in an age of ignorance of the causes of those diseases. (The Slave Trade)

France, the United States, Spain, Portugal, and even Brazil also freed a few slaves during their participation in the British-led campaign.

In the United States there was the Civil War, a genuinely unique event: I am aware of no other country in which one part of the dominant populace waged relentless, bitter warfare against the other part of the dominant populace in order, at least in part, to free from servitude a powerless, virtually voiceless minority. The cost is succinctly summed up by Wilfred McClay:

This war was, and remains to this day, America's bloodiest conflict, having generated at least a million and a half casualties on the two sides combined: 620,000 deaths, the equivalent of six million men in today's American population. One in four soldiers who went to war never returned home. One in thirteen returned home with one or more missing limbs. For decades to come, in every village and town in the land, one could see men bearing such scars and mutilations, a lingering reminder of the price they and others had paid. (Land of Hope: An Invitation to the Great American Story, Encounter Books, 2019)

Is this true of any other society that has ever existed on earth? When the United States is judged on the issue of slavery, it is worth asking what the standard of comparison is.

Practical & Moral Matters

Finally, there is the matter of practicality. Who is to decide who is entitled to receive reparations and on what basis? Given the long complicity of black Africans in the slave trade, surely having dark skin and an African pedigree would not be sufficient? It is dismaying to imagine the scramble among potential beneficiaries to demonstrate the fact of their descent from slaves, although it might prove highly profitable to the various genealogical enterprises already flourishing among us. Prudence requires serious reflection on both the impracticality and the moral ambiguity of the reparations campaign as a whole.

Christian charity was undoubtedly among the most important factors in the abolition of the slave trade and, finally, of the institution of slavery. Charity ought to dictate the response of American Christians to the lingering effects of slavery and its aftermath in our country. But the reparations campaign wants no part of charity. "Charity," in the understanding of many Americans of our time, means something like almsgiving—usually with a suggestion of condescension. The proponents of reparations are demanding that absolute, abstract justice, divorced from any sense of historical reality, be enacted in the actual world of living, breathing men and women.

Even if the project were possible, it would end in a travesty of real justice, which can only be realized if the particular deeds of concrete individuals are taken into account. A scheme to reward one segment of our people for being the descendants of those who were harmed and to punish and shame another segment for the (putative?) actions of (some of?) their ancestors would lead, at best, to an increase in bitterness and dissension among ethnic groups, or, at worst, to an aggravation of the totalitarian tendencies already disfiguring our political discourse and an increase in the excessive power of our central government over the everyday lives of Americans.

Christians, especially, ought to favor measures that address the lingering effects of the grievous suffering endured by Africans and their descendants as a result of slavery and the slave trade; nevertheless, the reparations campaign is a dubious means of bringing about understanding, justice, and amity between the diverse racial and ethnic groups in our country.

R. V. Young is Professor of English Emeritus at North Carolina State University, a former editor of Modern Age: A Quarterly Review, and the author of Shakespeare and the Idea of Western Civilization (Catholic University of America Press, 2022). He and his wife are parishioners at St. Ignatius of Antioch Church in Tarpon Springs, Florida. They have five grown children, fifteen grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on history from the online archives

15.6—July/August 2002

Things Hidden Since the Beginning of the World

The Shape of Divine Providence & Human History by James Hitchcock

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor