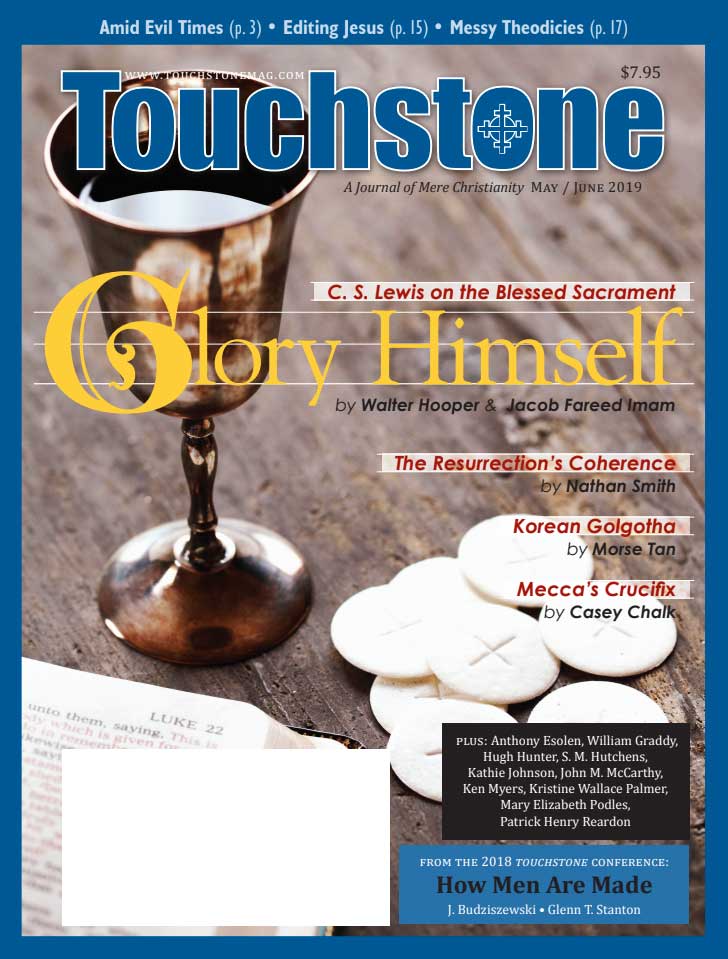

Feature

Glory Himself

C. S. Lewis on the Blessed Sacrament

by Walter Hooper & Jacob Fareed Imam

C. S. Lewis ends his one extended discussion of the Eucharist, in Letters to Malcolm, with a very telling line: "All this is autobiography, not theology." By this Lewis means that his reflections stem from a mixture of biblical and personal convictions about the nature of the Eucharist. Thus, before we examine Lewis's more theological considerations on the sacrament, we'll take a biographical sketch of Lewis as a parishioner.

Writing in 1931, not a year after his conversion, Lewis asked his brother:

By the bye, what are your views, now, on the question of the sacraments? To me that is the most puzzling side of the whole thing. I need hardly say I feel none of the materialistic difficulties: but I feel strongly just the opposite ones—i.e. I see (or think I see) so well a sense in which all wine is the blood of God—or all matter, even, the body of God, that I stumble at the apparently special sense in which this is claimed for the Host when consecrated.

Lewis and his brother returned to the faith of their youth at about the same time in 1931. And though Major Warren Hamilton Lewis—always called "Warnie"—never could boast of the riveting academic career of his brother, he always proved a worthy conversation partner. The two began attending Anglican liturgical services together at Holy Trinity Church in Oxford and dutifully appeared together every Sunday until 1952. In that year Father Ronald Head arrived.

Thirty years ago, Father Head visited the University of Oxford C. S. Lewis Society and presented a talk entitled "C. S. Lewis as Parishioner." He said the following:

When [Lewis and Warnie] first appeared at The Kilns, Father Wilfrid Thomas was Vicar, a Catholic-minded priest in a village which had been influenced by the Oxford Movement in various ways at least since 1867. Nevertheless, it was, interestingly enough, a village which had strong Methodist connections, antedating the Parish Church which had not been erected until 1849.

A new Vicar of low-Church outlook was instituted to the Benefice by the evangelical Bishop Strong of Oxford in 1936, and this incumbent remained until 1947, when the return of the pendulum began with my predecessor in 1947, and reached the status quo ante on my appearance later on.

The Oxford movement, which Father Head references, began about fifty years after the Evangelical movement. The Evangelicals under Wesley took a radical approach to the Bible, interpreting it with a literalist hermeneutic. The Oxford movement, on the other hand, re-adopted ancient tradition by returning to a vibrant sacramental life. In the 1830s, it was very uncommon for a Eucharistic celebration to occur every week at an Anglican church—perhaps a large parish would celebrate it once a month. For Keble, Newman, and Pusey, the founders of the Oxford movement, to hold a Eucharistic service every week, and pray Matins and Evensong every day was quite radical in another direction. A hundred years after the Oxford movement began, Father Head was continuing the work of Keble, Newman,

and Pusey.

By the time Father Head arrived, Warnie had become quite involved in the parish, serving on the parish council and as churchwarden. He continued this after Father Head's arrival—though he was not well pleased with some of the changes Father Head made.

In the mid-twentieth century, the sung services proved the most popular Sunday liturgy for Anglicans. Usually beginning around 11:00 a.m., the sung services were a crowd favorite over and beyond the Eucharistic celebration, held at the ungodly hour of 8:00 a.m. The brothers Lewis dutifully appeared at the 8:00 a.m. Holy Communion service on Sundays "without fail," as Father Head remarked, but the reverend was enough of a gentleman to hide some secrets from his public address at the Society.

Father Head rescheduled these services—giving the Eucharistic liturgy the prime spot of 11:00 a.m. in the hopes of increasing Eucharistic devotion in his parish. He believed that the Eucharist was essential: the people needed the pure presence of God. He did not rid the parish of Morning Prayer, but he placed it before the Eucharistic service, as was traditionally done.

This scandalized Warnie who, though a faithful communicant at the Eucharistic liturgy, thought that the new Sunday line-up was "too Roman" for his liking. Once his brother died, Warnie began attending Highgate Church's Matins service (composed of psalms and hymns). This was the reason many low-churchmen went to Highgate: they knew they could find Matins late in the morning. Warnie, like many others, believed this to be more essential than the Eucharist—not least because he was brought up with it. But it must have been rather bizarre for Father Head to see Warnie remain on the parish council, as he did, and attend another parish without the same popish predilections.

Reasons for Silence

The change did not disturb C. S. Lewis in the same way. Lewis had by this time developed a mystical understanding of the Blessed Sacrament, and the devotion of his new parish priest only reinforced this understanding. Lewis spoke of and referred to the Eucharist more in the years after 1952 than he did in the twenty years before as a Christian author. It seems that the body of our Lord became an ever-greater source of contemplation for him under the leadership of the new high-church vicar.

Nonetheless, Lewis never wrote a discourse on the Blessed Sacrament, for a very practical reason: he was not a theologian. In Letters to Malcolm, he writes:

You ask me why I've never written anything about the Holy Communion. For the very simple reason that I am not good enough at Theology. I have nothing to offer. Hiding any light I think I've got under a bushel is not my besetting sin! I am much more prone to prattle unseasonably. But there is a point at which even I would gladly keep silent. The trouble is that people draw conclusions even from silence. Someone said in print the other day that I seemed to "admit rather than welcome" the sacraments.

Lewis had hoped to be as ecumenical as possible so he would not alienate more baptized than necessary—but this approach led people to draw false conclusions about him. In chapter nineteen of the very last book he wrote—which was only published posthumously—he finally spoke openly to silence the critics. Everyone had been waiting to hear what Lewis truly believed about the Eucharist—and so we will wait until the end of this article to discover it for ourselves. But before Lewis revealed his position, he admitted to one other reason that had kept him silent up until that point:

The very last thing I want to do is to unsettle in the mind of any Christian, whatever his denomination, the concepts—for him traditional—by which he finds it profitable to represent to himself what is happening when he receives the bread and wine. I could wish that no definitions had even been felt to be necessary; and, still more, that none had been allowed to make divisions between churches.

The concepts he finds profitable—this is a rare moment when Lewis fancies a person's preference before the truth. But Lewis is as much being historical as he is being prudent—if such a distinction can be made. By this we mean that Lewis, as a professor of Medieval and Renaissance literature, knew that few issues had caused as much ink to be spilt in the Medieval church and then more schisms to occur in the Renaissance than the doctrine of the Blessed Sacrament.

The Flesh of Our Savior

According to Joseph Goering, "the term 'transubstantiation' 'transubstantio' (a precursor to 'transubstantiatio') was first introduced at Paris around 1140, most likely by Robert Pullen, to explain an affirmation about Christ's presence in the sacrament that was already assumed and taken for granted." What is certain is that, in its original meaning, the word "transubstantiation" had no connection with the influence of Aristotle's philosophy: it simply referred to the banal category of substance to express the changing (Latin conversio) of bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ, as stated by the faith of the Church from the Patristic period.

The early Church was unanimously convinced that Christ was truly, bodily present in the Eucharistic celebration. St. Ignatius of Antioch, traditionally known as the disciple of John the Evangelist, writing around a.d. 105, condemned those who "abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness, raised up again." Similarly, in 150, St. Justin Martyr wrote:

Not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.

The early Church understood Jesus himself not to have minced his words. During the Bread of Life discourse in John 6, he says, "I am the living bread who came down from heaven, and the bread that I will give is my flesh." The Jews who were there were murmuring, but after Christ says this, they begin to quarrel. They do not appear to understand Jesus to be speaking symbolically. Throughout John's Gospel, Jesus makes statements such as, "I am the gate," "I am the vine," and the like. But when he says in chapter 6, "I am the bread of life," the Jews retort: "How will this man give us his flesh to eat?" Jesus does not clarify that he is speaking metaphorically, but that he is speaking literally. He replies to them, reiterating his point in five different ways:

Truly, truly I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you do not have life in thee. Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood have eternal life, and I will raise them up on the last day; for my flesh is true food and my blood is true drink. Those who eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me, and I in them. Just as the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so whoever eats me will live because of me. (John 6:53–57)

During this clarification, Christ stops using the Greek word fagein and instead begins to use trōgein—the latter connoting a visceral chewing—to solidify the fact that he was talking about a literal eating.

The crowds reply: "'This teaching is difficult; who can accept it?' . . . Because of this, many of his disciples turned back and no longer went about with him." This is the only passage in which the Sacred Scriptures speak of a time when disciples left Christ because of his teaching—and it was his teaching on the Eucharist.

Doctrinal Skirmishes

So Lewis was right, this was a complex issue from the very beginning. It became an even greater squabble in the eleventh century, when Berengar of Tours declared the Eucharist to be merely a symbol. At this same time, the Albigensian heresy, that all matter is evil, was spreading like wildfire. These attacks on the Eucharist concentrated the Church's mind on a defense of the Eucharist. No one has to define a doctrine until he has to defend it. The Scholastic theologians were keen to develop the doctrine of the Eucharist in order to reassure the faithful.

St. Thomas Aquinas would ultimately champion the debates. He utilized Aristotle's bifurcation of the world into accidents and essences. Aristotle taught that an object's essential property is a property that it must have, while its accidental property is one that it happens to have but that it could lack. For example, if you chop off a man's arm, he'll still be a man. His substance has not changed.

Three hundred years after Thomas died, the Council of Trent was convened, where the fathers, using the Aristotelian distinction wrote:

Because Christ our Redeemer said that it was truly his body that he was offering under the species of bread, it has always been the conviction of the Church of God, and this holy Council now declares again, that by the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood.

The Church felt compelled to define this doctrine officially because of the Protestant doctrinal skirmishes over the Eucharist. Luther claimed Christ was present bodily, beautifully writing: "If we eat Him spiritually through the Word, He abides in us spiritually in our soul; if we eat Him physically, He abides in us physically and we in Him. As we eat Him, He abides in us and we in Him." However, Luther was very wary of the popish doctrine of transubstantiation that was

emerging.

Zwingli, like Berengar of Tours five centuries prior, held that the Eucharist was merely symbolic, as did Thomas Cranmer, though the latter did not force the entire Anglican communion to sit in accord with his belief—he tolerantly allowed them to believe in the Real Presence. He did, however, disallow belief in transubstantiation. And, beginning with Charles I, all English sovereigns were required to denounce the doctrine of transubstantiation upon assuming the throne. The denouncement reads as follows:

I, A.B., by the grace of God King (or Queen) of England, Scotland, and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, do solemnly and sincerely in the presence of God, profess, testify, and declare, that I do believe that in the Sacrament of the Lord's Supper there is not any Transubstantiation of the elements of bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ at or after the consecration thereof by any person whatsoever.

King George V ended this ritual. He said that he did not want to alienate a third of his population. That was in 1910, about the time when young Lewis was beginning to translate Homer.

The Holiest Object

Lewis, as an Anglican himself, was quite glad of Cranmer's tolerance. Most likely from the influence of Tolkien, Chesterton, and the high Anglican priest who served at Holy Trinity until 1936, Lewis began meditating on the Real Presence of God in the Eucharist. Writing again to his brother on December 3, 1939, he approvingly refers to St. Francis de Sales's argument for frequent communion in his Introduction to the Devout Life, which reads: "As mountain hares become white in winter because they neither see nor eat anything but snow, so by adoring and feeding on beauty, purity and goodness in the Eucharist you will become altogether beautiful, pure, and good."

People say that as married couples grow old, they begin to look like one another. The more you live with someone, the more you think, act, and even look like him. Such is St. Francis's argument for receiving the Eucharist often—one will begin to live, think, act, and even look like Jesus Christ.

A couple of years after Lewis wrote this letter, he ascended the pulpit in the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin in Oxford. World War II had begun, and he was about to deliver "The Weight of Glory," one of the most beautiful sermons of the past century. As the students and dons listened, they heard Lewis describe how we have grown to be half-hearted creatures, fooling about "with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us. . . . We are far too easily pleased." Lewis commended his audience to look elsewhere for their joy and to await the glory that is bound to come

with it.

He concludes this sermon by giving fair warning to his listeners: it "may be possible for each to think too much of his own potential glory hereafter; it is hardly possible for him to think too often or too deeply about that of his neighbour." His final words:

Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbour is the holiest object presented to your senses. If he is your Christian neighbour he is holy in almost the same way, for in him also Christ vere latitat—the glorifier and the glorified, Glory Himself, is truly hidden.

Vere latitat, truly hidden—Lewis here quotes from St. Thomas Aquinas's private prayer for adoration of the Blessed Sacrament. Adoro te devote, the name of the saint's prayer, seems to have had a profound effect on the Oxford don, and it may be worth quoting the first two stanzas to read the depth of Thomas's contemplation:

Godhead here in hiding, whom I do adore,

Masked by these bare shadows, shape and nothing more,

See, Lord, at Thy service low lies here a heart

Lost, all lost in wonder at the God thou art. . . .Thy wounds, as Thomas saw, I do not see;

Yet Thee confess my Lord and God to be.

Make me believe Thee ever more and more,

In Thee my hope, in Thee my love to store.

This, of course, does not imply a particular metaphysic of the Eucharist, but only a determined sense to worship God, whose presence somehow dwells within the physical elements of bread and wine.

Affirming the Real Presence

So far Lewis has cited St. Francis De Sales and St. Thomas Aquinas. He drinks at least one pint a week with good Catholics such as Tolkien and the Dominican priest Gervase Mathew. Is he being won over to the view of transubstantiation?

In his sermon "Transposition," also delivered in 1941, this time in Mansfield Chapel, Oxford, for Pentecost, Lewis called attention to the spiritual phenomenon of the "higher [celestial] reproducing itself in the lower [terrestrial]." This act of the higher assuming the lower he continues to explicate later in the sermon:

But in the case we started from—that of emotion and sensation—we are even further beyond mere symbolism. For there, as we have seen, the very same sensation does not merely accompany, nor merely signify, diverse and opposite emotions, but becomes part of them. The emotion descends bodily, as it were, into the sensation and digests, transforms, transubstantiates it, so that the same thrill along the nerves is delight or is agony.

The higher descending to the lower, the terrestrial glorified into the celestial. If this were all we knew, we might be tempted to think that Lewis believed in transubstantiation.

But the next year, Lewis published The Screwtape Letters. He begins Letter Sixteen with: "Dear Wormwood, You mentioned casually in your last letter that the patient has continued to attend one church, and one only, since he was converted, and that he is not wholly pleased with it." Screwtape expounds a tactic in which to make the Patient—that is, the Christian—anti-ecumenical, writing: "The real fun is working up hatred between those who say 'mass' and those who say 'holy communion' when neither party could possibly state the difference between, say, Hooker's doctrine and Thomas Aquinas', in any form which would hold water for five minutes."

Anyone who believed in transubstantiation would not be so hesitant to allow others to get this wrong, for the doctrine was specifically constructed to affirm God's presence. Indeed, our suspicions would be confirmed in a letter of 1945, where Lewis writes, "The doctrine of Transubstantiation insists on defining [the Eucharist] in a way which the New Testament seems to me not to countenance." He does not defend this claim in this passage.

We must pause for a moment over the above quote from Screwtape: both the Catholic Thomas and the Anglican Hooker affirmed the real, bodily presence of Jesus in the Eucharist. Lewis implies that even the devils know that God is in the Sacrament.

The Sacramental View of Man

If one were ever to ask Lewis why he believed what he believed, he would respond at some point that Hooker had a lot to do with it. Lewis once wrote that Hooker's Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity "is to me the great formulation of Anglicanism." We may not be straying too far in speculating that Hooker's position would reveal Lewis's own.

The three sacraments of the faith, according to Hooker, are belief, baptism, and the Eucharist. We find the same division in Lewis's Mere Christianity: "There are three things that spread the Christ life to us: baptism, belief, and that mysterious action which different Christians call by different names—Holy Communion, the Mass, the Lord's Supper. At least, those are the three ordinary methods."

It seems that Lewis may have St. Paul's first letter to the Corinthians in mind, where Paul speaks about refraining from the pagan sacrifices and instead approaching the table of our Lord. "Because there is one bread, we who are many are one body" (cf. 10:17). By eating the bread, which is his body, he enters into us, we in him, and the entire Church is bound together. Lewis clarifies how these three sacramental acts sanctify the person:

This new life is spread not only by purely mental acts like belief, but by bodily acts like baptism and Holy Communion. It is not merely the spreading of an idea; it is more like evolution—a biological or super-biological fact. There is no good trying to be more spiritual than God. God never meant man to be a purely spiritual creature. That is why He uses material things like bread and wine to put the new life into us. We may think this rather crude and unspiritual. God does not: He invented eating. He likes matter. He invented it.

If man were able to consent to the gospel only in his heart, then the body would be worthless, or even a hindrance in his spiritual pilgrimage. Lewis does not believe that God created the body to be at enmity with the soul: the material body must not hinder but help man in his celestial ascent. The Word became flesh, became matter, became body. The incarnate Word has redeemed the body, enabling man to use it in right ritual and right worship. Now, the body must profess the creed.

Lewis found that the sacrament changes the way we see the world—such as, for example, the sexual assumptions that were rapidly changing even in his day. He writes in a letter of 1955:

And indeed now that contraceptives have removed the most disastrous consequences for girls, and medicine has largely defeated the worst horrors of syphilis, what argument against promiscuity is there left which will influence the young unless one brings in the whole supernatural and sacramental view of man?

The sanctity of the body is quickly dismissed if one dismisses the realness and gravity of the sacraments. When the body is used in sacred ritual, then one does not as easily use it for profane acts. Yet the sacraments do not merely help a person recognize his or her own dignity but also that of the world.

In another letter of 1955, we find an answer to Lewis's letter to Warnie way back in 1931 when he said that he saw all wine as the blood of God.

Even now, at my age, do we often have a purely physical pleasure? . . . So that the physical pleasure is also imaginative and even spiritual. Every meal can be a kind of lower sacrament. 'Devastating gratitude' is a good phrase: but my own experience is rather 'devastating desire'—desire for that-of-which-the-present-joy-is-a-Reminder. All my life nature and art have been reminding me of something I've never seen: saying 'Look! What does this—and this—remind you of?'

Now he does not stumble at the apparently special sense that is claimed for the Host when consecrated, but finds that the consecrated Host, and its likeness to the external world, is the cause for seeing everything as reminders of the sacrament, of God's manifestation in the world. The sacraments help us recognize our own dignity and that of the rest of creation.

Christ's Command

So now we are coming full circle. We have heard the answer to Lewis's first musings on the Sacrament. Now we have nowhere left to go but to Letters to Malcolm. Here Lewis writes at the end of his life:

I do not know and can't imagine what the disciples understood Our Lord to mean when, His body still unbroken and His blood unshed, He handed them the bread and wine, saying they were His body and blood. I can find within the forms of my human understanding no connection between eating a man—and it is as Man that the Lord has flesh—and entering into any spiritual oneness or community [Greek: koinônia] with him. And I find "substance" (in Aristotle's sense), when stripped of its own accidents and endowed with the accidents of some other substance, an object I cannot think [of]. My effort to do so produces mere nursery-thinking—a picture of something like very rarefied Plasticine. . . .

The command, after all, was Take, eat: not Take, understand.

It is odd to read these last lines from the author of the Chronicles of Narnia. Lewis himself demonstrated better than most that images for children can be infused with profound theological truth. Why is it that Lewis, who had one of the most enviable theological imaginations, struggled to imagine this? Perhaps part of the answer could be found in Tolkien's unpublished essay, the "Ulsterior Motive." But this is conjecture and we will cease our speculations here.

Perhaps at first we can sympathize with Lewis's concern over Jesus' command, "Take, eat: not Take, understand." But at the same time, we may be denying something immensely important if we forego our ability to analyse the Eucharist. Being able to speak about the Eucharist in like terms of other material objects affirms the humility of God. We shirk the full weight of the incarnation by declaring that we cannot exercise that level of analysis on the Eucharist. Why can we analyse the person of Christ, stating that he has a hypostatic union, that he is fully God and fully man? It is because he was incarnate. Why can we even analyse the Trinity? It is because the Second Person of the Godhead descended unto us, externalizing the interworking of the Divine. Only because God became embedded in the material world can we begin to analyse him—and thus analysis becomes a creedal affirmation of God's glorious descent.

So, does this mean that Lewis rejected the real presence? He continues:

I get on no better with those who tell me that the elements are mere bread and mere wine, used symbolically to remind me of the death of Christ. They are, on the natural level, such a very odd symbol of that. . . . Again, if they are, if the whole act is, simply memorial, it would seem to follow that its value must be purely psychological, and dependent on the recipient's sensibility at the moment of reception. And I cannot see why this particular reminder—a hundred other things may, psychologically, remind me of Christ's death, equally, or perhaps more—should be so uniquely important as all Christendom (and my own heart) unhesitatingly declare.

If Lewis's critique of transubstantiation is that the Lord told us to "Take, eat: not Take, understand," then his critique for the mere memorial ritual is: The Lord also did not say, "Take and be sensible." The sacraments are gifts for man that depend on the power of God, not man's emotional awareness. To demand our emotional response would be giving a nod to the early heresy of Semi-Pelagianism.

Not "What?" but "Who?"

Lewis ends this chapter: "Particularly, I hope I need not be tormented by the question 'What is this?'—this wafer, this sip of wine." "What is this?"—did Lewis know that he was translating the Hebrew word manna? "What is this?" That was the question for the Jews.

Speaking of wafers, the Catholic Church chose the inglorious wafer to consecrate based upon the Torah's description of manna in Exodus 16:31: "The people of Israel called the bread manna. It was white like coriander seed and tasted like wafers made with honey." Honey should remind us of the land flowing with milk and honey. A foretaste of the Promised Land.

There was an expectation that arose in Jewish tradition that the Messiah, as he would be a second Moses, would bring back the manna from heaven. For instance, 2 Baruch speaks of what "shall come to pass when . . . the Messiah is to be revealed. . . . And it shall come to pass at that self-same time that the treasury of manna shall again descend from on high, and they will eat of it in those years." They believed the Messiah would restore Israel's store of manna.

According to the Babylonian Talmud, whenever the people would ascend to Jerusalem for a festival, the priests would reveal the manna to them, the manna that God commanded Moses in Exodus to keep in the tabernacle. The Babylonian Talmud records that the priests "used to lift up the golden table in the temple and exhibit the Bread of the Presence on it to those who came up for the festivals, saying to them: 'Behold, God's Love for you!'" The Bread of the Presence (lakhem ha-panīm) can be translated as the Bread of the Face. Whose Face? Jesus answers this:

I am the bread of life. Your fathers ate the manna in the wilderness, yet they died. This is the bread that comes down from heaven so that anyone may eat of it and not die. I am the living bread that came down from heaven. If anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever. And this bread, which I will give for the life of the world, is My flesh. (John 6:48–51)

Lewis says that he hopes not to be asked, "What is this?" But the proper and necessary question is, "Who is this?"

I, Walter, remember partaking of the sacrament next to Lewis. I watched him carefully. Each time the priest would raise the Host, he would gasp—it seemed to me that he truly believed that he was seeing God. A few months on, Lewis was no longer able to attend Eucharistic services with Father Head, so Father Head would visit him in his home. Lewis would clear off his desk so that the priest could celebrate a Eucharistic service for him. It was next to his desk, which was his makeshift altar—where he devotedly adored his Lord and wrote for us—loved God and loved his neighbor—that Lewis died.

Walter Hooper served as C. S. Lewis’s secretary at the end of Lewis’s life. Since Lewis’s death in 1963, Walter has been the literary executor of the Lewis estate.

Jacob Fareed Imam is a Marshall Scholar, doctoral student, and former president of the C. S. Lewis Society at the University of Oxford. He is the managing director at Catholics 4 Truth & Justice.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on C. S. Lewis from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor