A Thousand Words

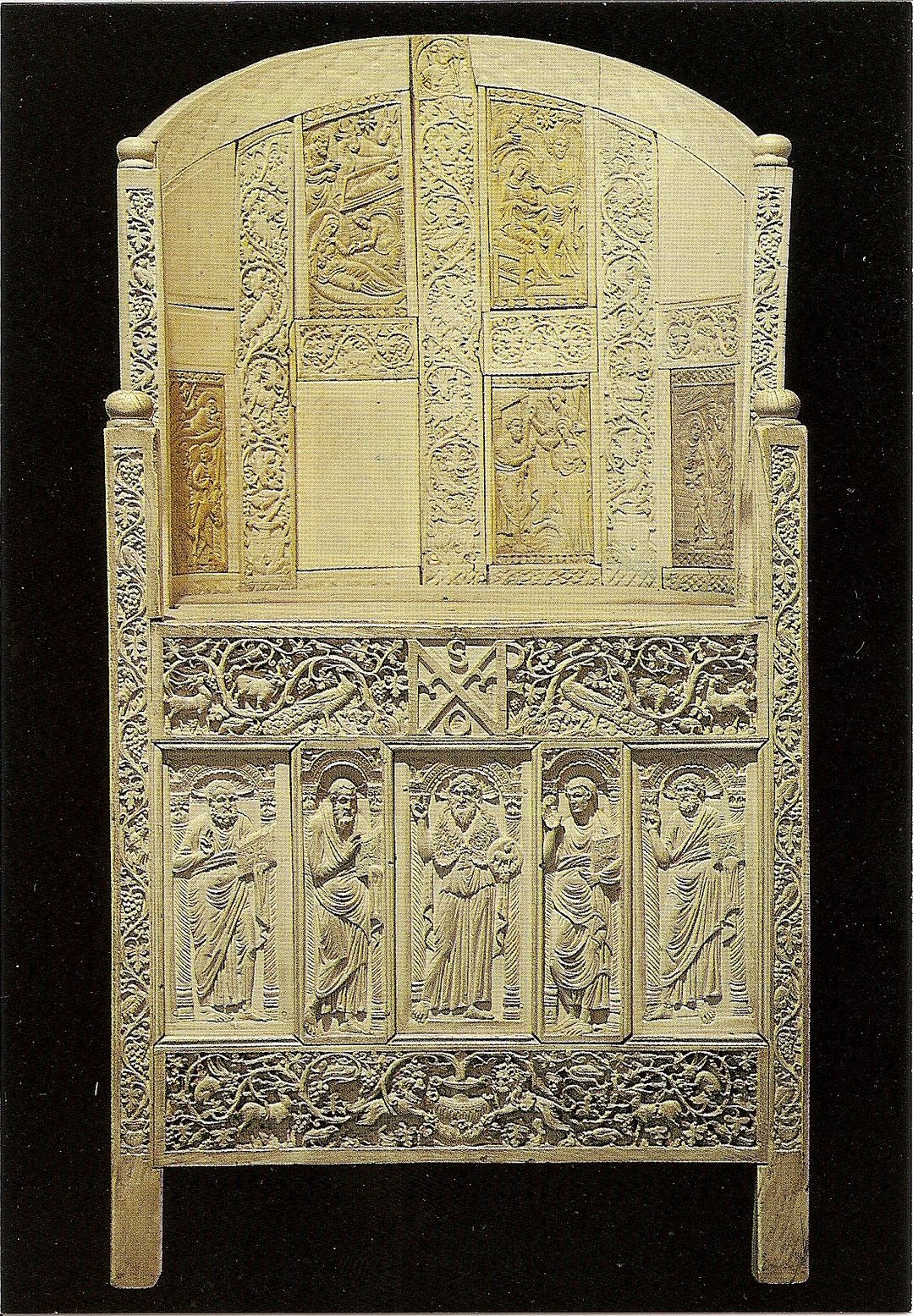

The Throne of Maximianus

by Mary Elizabeth Podles

The sixth-century Throne of Maximianus stands close to five feet tall; its wooden armature is completely paneled in ivory, front, back, and sides. Since antiquity, ivory has been a luxury due to its rarity, difficulty of acquisition, and cost of transport, as well as its inherent qualities of fine grain, creamy color, and silky luster, all of which catch and hold the light. The panels of the throne are narrow, obviously limited by the width of the tusks; eight of them have vanished over the course of the centuries. Still, it remains the most impressive monument of Early Byzantine sculpture in the world.

We know or can deduce some of the throne's history. It was most probably commissioned by the Emperor Justinian as a gift to Bishop Maximianus of Ravenna for the dedication of the Church of San Vitale in a.d. 547. During the disintegration and fall of the Western Roman Empire, Ravenna was made the capital city, first of the waning empire, and then of the subsequent Ostrogothic Kingdom. The Byzantine emperor, Justinian, formulated a bold plan to reintegrate the empire through a diplomatic and (mostly) military campaign to reconquer Italy, North Africa, and the shores of Mediterranean Spain.

Ravenna was successfully recaptured in 540. Its site on the Adriatic and its history as the capital made the city the logical choice for Justinian's Italian seat of government. Justinian appointed Maximianus archbishop and, because of the close connection of church and state, de facto regent of the emperor. Maximianus, originally from the Dalmatian city of Pula, had risen through the clerical ranks as a protégé of Justinian, and found himself to be an extremely unpopular choice for Ravenna. As an antidote, he launched a massive and generous building campaign, culminating in the dedication of San Vitale in 547, at which time the Throne of Maximianus would have been unveiled.

The Carvings

As a rule, thrones were restricted to emperors, kings, popes, and bishops. This, a bishop's throne, bears imagery suited to the bishop's proclamation of the gospel. The front panels portray the four Evangelists, together with John the Baptist, the first herald of the Word. The five figures are carved in low relief, and squeezed into an arcade of narrow niches, each topped with a halo-like conch. Sculpture in the round was frowned upon in the Byzantine East, as it was equated with the pagan idols of Antiquity. Similarly, the figures' proportions are unclassically elongated and abstract. A lively abstract rhythm of shifting weights, tilted heads and hands, and swirling drapery links the figures across the arcade into a coherent whole, even though they seem to have been carved by two different artists.

Around the figures, still another artist has carved decorative bands of vine leaves, symbolic of Christ, the true vine. Here and there the vines are punctuated with grapes, and peopled with heraldic animals: the peacocks of the Resurrection, the lions of Solomon's throne. The lions are just below the Baptist's feet, while Maximianus' insignia is just above his head, and if to suggest a parallel between the bishop's judicial role and Solomon's.

Scenes from the life of the Virgin and of Christ cover both sides of the chair back. Many of the scenes from Mary's story come from the apocryphal Protoevangelion of James, a precedent that will recur in Byzantine art up to the present day. These panels seem to have been carved by a number of different hands, though they share a consistent horror vacui: every available millimeter is filled with decorative details (see the detail in the Nativity panel). The fact that both the front and the back surfaces are elaborately paneled suggests that the chair was meant to be free-standing, not set against the wall in the usual fashion, or even that it was carried in procession like a sumptuous icon of the bishop's authority, and, in absentia, the emperor's.

Why Joseph?

On the outer sides and arms of the throne, ten panels tell the Old Testament story of Joseph and his brothers, an unusual subject at this time. Some scholars propose that the story of the Egyptian Joseph points to an Egyptian origin for the carvings on the chair. A famous school of ivory carving existed in Alexandria. The project might have been begun there, but then cut short by the Plague of Justinian in 540, which came out of Africa and followed the ivory route around the ports of the Mediterranean. Some of the panels are a bit sketchy in execution, as if finished in a hurry by less-skilled artisans.

Others argue, however, that the story of Joseph might have been included for purely symbolic reasons. Joseph, a foreigner, served as an important minister to Pharaoh, just as Maximianus, in his role as bishop, served the emperor and had a major hand in the civic government of Ravenna. Justinian did not attend the dedication of San Vitale in person, but among the mosaics of the chancel is a portrait of Justinian and his retinue that stood in for his real presence. Maximianus, prominently labeled, stands at the emperor's elbow; around him are clerics with a jeweled Gospel book and censer (and at the far left, his bodyguards). The prominent placement of the mosaics in the chancel close to the apse establishes Justinian, and Maximianus with him, as Christ's own regents on earth, in eternal attendance at the Eucharist as long as San Vitale stands.

Mary Elizabeth Podles is the retired curator of Renaissance and Baroque art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. She is the author of A Thousand Words: Reflections on Art and Christianity (St. James Press, 2023). She and her husband Leon, a Touchstone senior editor, have six children and live in Baltimore, Maryland. She is a contributing editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on art from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor