Feature

The Still Small God

The Mustard Seed & the Wonders of His Kingdom

To be a Christian, I have come to see, is not to believe that all of the creatures of this far-flung universe—from the flame of a billion stars in the Andromeda galaxy to the glimmer of a firefly, hardly seen before it vanishes in the twilight—can be united in Christ. It is to believe that only in Christ can they be united, because only in Christ are the infinite and the infinitesimal, the Creator and the creature, the necessary and the contingent, the eternal and the ephemeral, bound together in a single person, the person of Christ.

That is what the wise Chesterton was getting at in a little poem with an immense title, "The Holy of Holies." The title is rather like one end of a riddle. When we see it, we expect a poem about that inner sanctum of the Jewish Temple, where the high priest would enter once a year, on the Day of Atonement, to make sacrifice for all the people, and to utter, just that once and on his lips alone, the holy name of God, I AM. Such a poem almost writes itself. We can see the stains of blood, so plentiful, over so many hundreds of years, that the stones themselves cry out with the animals slain thereon; and we can hear the voice of the priest, trembling with fear, as he whispers that name with nary a genuine consonant in it, a name like the breath of God stirring above the waters in the beginning.

Yet if we think about it some more, perhaps a Christian poet would not direct our attention to the edifice and its secret chamber. Jesus said, when his apostles were playing the role of tourist guides and marveling at the grandeur of Jerusalem, that not one stone of that Temple would remain upon a stone. They must have heard it with sinking hearts, for surely it is one of the sweetest things in friendship to enjoy together the sight of what is grand and holy and beloved of one's people. They did not know then that Jesus himself would be their one and only high priest, penetrating beyond the veil, as the writer to the Hebrews puts it, or rather, allowing the veil of his flesh to be torn in two, making a sacrifice of his own blood to atone for the sins of men once and for all. "Tear this temple down," he says, "and I will raise it again in three days."

The Infinite in the Tiny

Perhaps, then, Chesterton is going to give us a poem about the high priesthood of Christ. I think he does, but not as we expect. There is no reference to the Temple at all, and no direct reference to Christ. Yet Christ is there, the one through whom all things were made, and who spoke the parable about the kingdom of God that is the inspiration for the poem. Here is the poem in all of its minuscule immensity:

'Elder father, though thine eyes

Shine with hoary mysteries,

Canst thou tell what in the heart

Of a cowslip blossom lies?'Smaller than all lives that be,

Secret as the deepest sea,

Stands a little house of seeds,

Like an elfin's granary.'Speller of the stones and weeds,

Skilled in Nature's crafts and creeds,

Tell me what is in the heart

Of the smallest of the seeds.''God Almighty, and with Him

Cherubim and Seraphim,

Filling all eternity—

Adonai Elohim.'

Our God is not big, like Mister Zeus, perched upon his throne on Mount Olympus, and bending his attentive brows to behold the deeds of men, making sure that they are just, unless he happens to be distracted by his nagging wife Hera or by an especially lissome shepherdess momentarily alone and vulnerable in the fields. Such bigness is trivial, even contemptible. Our God is the immortal, invisible, God only wise: and he would not be the infinite God were he not infinitely present within each of the tiniest things he has made. The smallest of all the seeds is as great as all the universe, because God dwells within it, and not a piece of him, either; all of the heavenly hosts are there, singing and praising him forever.

The Smallest Parable

Of course Chesterton is thinking of that smallest of all of Jesus' parables. "The kingdom of God may be likened unto a mustard seed," says Jesus, "which is the smallest of all the seeds, but when it grows it becomes the greatest of the shrubs, and the birds of the air build their nests in its branches." We are apt to think that the parable has to do with the lowly beginnings of the Kingdom, beginnings that are then swallowed up in greatness and never seen again. The seed of the Kingdom becomes, what?—an Emerald City, governed by the great and powerful Oz? We can find that sort of thing all over the place in pagan and modern secular myth. What was Rome in her infancy? A couple of foundling boys suckled by a she-wolf. What was America in her infancy? A company of sick and hungry Puritans putting ashore at Plymouth in bad weather. What was the Bolshevik Revolution in its infancy? The gray little Lenin showing up at the Finland Station, with murder and political theory in his heart.

In such cases we use the smallness of the beginning as evidence of something unexpected and even wondrous, yet we are ever in danger of forgetting that smallness, or of seeing it only as a term of happy comparison. We show the great man or great nation as coming from humble beginnings, but unless we are filled with the true spirit of the Christian faith, we never show them as returning to that humility. I am not saying that there is anything inherently wrong about gazing in wonder at the great things God has wrought from nothing. If you will excuse the irreverence, God may be likened to the rascal thief Autolycus in Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale, who calls himself "a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles." Jesus himself is, as St. Peter says, thinking about the Psalms, "the stone which the builders rejected, that has become the cornerstone." By the Lord has this been done, and it is wonderful in our eyes.

And yet let us return to that parable, because there is something odd about it. Jesus does not say, "The Kingdom of God may be compared to the cedar of Lebanon, the mightiest and most beautiful of all the trees, even though it came from a small seed." The emphasis is not on the great but on the small. That mustard seed does not produce a tree one hundred feet tall. It produces a big shrub. Its limbs are not cut down and hewn to fashion ornamental doors for the Temple or the palace of the king. Its limbs are not cut down at all. They are let be, and birds build nests in them. The mustard trees are big enough for the sparrows.

In the Christian faith the small is not transcended and dismissed. The Christian faith is not a towering edifice of steel and concrete and glass, without a human face, without a trace of human handiwork—a sort of thing that a machine would make, if a machine could make things, erecting it upon the dust of what had once been human habitations. Jesus does not say, "The kingdom of God may be likened unto a man who had one pearl of great price. And he sold that pearl, and with the proceeds he bought many fields, and became the richest and most powerful man in his nation." Jesus does not say, "Unless you cease being as little children, so that the world may take you seriously, you shall not enter the kingdom of God." Jesus does not enter Jerusalem in a chariot.

A Dazzling Point of Light

Recall the first prophecy uttered by John the Baptist: it was without sound, without words, when he leapt in the womb of his mother Elizabeth, to greet the coming of his Lord. Recall the one truly new and re-creating event in the history of the world: the Incarnation, when the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us. Even the night in Bethlehem was too noisy and too great for the Word's entry into the world. Well did the old masters do when they painted the Virgin Mary in an enclosed garden, itself walled like a Holy of Holies, as she meditated upon the word of God. And she replied to the angel, "Be it done unto me according to thy word." At that moment, the false and insensible flesh of the world, that blister, that diphtherial curtain, was torn asunder, and Christ our brother was incarnate. Says the poet John Donne, addressing Mary:

Ere by the spheres time was created, thou

Wast in His mind, who is thy Son, and Brother,

Whom thou conceiv'st, conceiv'd; yea thou art now

Thy Maker's maker, and thy Father's mother,

Thou hast light in dark; and shutst in little room

Immensity cloistered in thy dear womb.

What we say about extent in space we say also about duration in time. Mr. Zeus may be imagined as an immortal, though he was once born. All that means is that the world will be burdened with him, the consummate politician, as long as there is a world for him to knock around in. Mr. Zeus is not eternal. Which do we suppose is closer to eternity, a year, even a millennium, or an instant? If we finite creatures who float upon the river of time cannot imagine what it is to be beyond time, in that heaven for which the flow of the river is as a single present moment, so too we cannot imagine what it is to be fully within a single instant of time, an instant without dimension, within whose present are contained the potentialities of all times.

God dwells in inaccessible light, and the eternal and the instant are alike inaccessible to us, "dark with excess of bright," as Milton says. The praise of the angels within the smallest of the seeds resounds, "filling all eternity," says Chesterton. The immensity of God the Creator was enclosed within the womb of Mary, even within the single cell.

In the Paradiso, Dante's first vision of God is as of an insuperably dazzling point of light, not an orb but a point, so small that the smallest star in our heavens would seem like a moon by comparison. We should not simply say that God appears to Dante as a point because Dante is far away. The point has no dimension. Zeus would grow bigger, the closer you drew to him, and that is because Zeus is merely and trivially big, while God is the one for whom the whole universe is as a point, and a single created point of space is room enough for him. In what analogous and small event is enclosed the eternity of God the Redeemer?

A Movement of the Heart

Consider a moment that is as small in time as a seed is small in space. Consider something tinier than a mustard seed: an impulse of the human heart, an act of the will that is touched by the silent and invisible dew of God's grace. The scene is Calvary, and the two men crucified beside Jesus have been mocking him. "If you are the Son of God," they cry, "save yourself and us! Come down off that cross!" They seek some act of obvious grandeur and power. They would be pleased by a triumphal parade, the victorious general leading the slave-driving Romans in chains through the gates of Jerusalem. They want twenty more years, or thirty, or forty—of debauchery, highway robbery, assassination, treachery, and all the other pleasures of the adventurous life. They want more of the same old big empty things they have known for so long, just as a merchant wants gold and a politician wants power and a soldier wants glory and a lawyer wants fees. They want a big house for a long time. They do not want the kingdom of heaven, forever.

What happens then? We are not told. One of the mockers rebukes the other—but something must have turned in his heart before then. These were wicked men who deserved their punishment. An impulse of the heart, the smallest and most secret response to the call of God: like the glint of a spiritual firefly; private, hardly understood by the very man who experiences it; a momentary turn; the lift of one feather; the twinkling of an eye. "We shall all be changed," says St. Paul, thinking of the resurrection, "in the twinkling of an eye," that wonderful momentary glimmer of affection and humility and delight. Something happens, and the thief who has been so bad says to Jesus, "Lord, remember me when you come into your kingdom." This is the mustard seed; this is the speck of yeast in the dough. "Truly I say to you," says Jesus, "this day you shall be with me in Paradise."

And we are present for this event, which passes everyone by with hardly a glance. Imagine a butterfly against an elephant; so is this event to the massive and stupidly potent Roman Empire. Yet it is an event that sees, as Shakespeare says in that same play The Winter's Tale, "a world ransomed, or one destroyed." Something happens. In the darkness of non-being—something happens, the explosion of a universe into existence, the turn of one human soul to his Redeemer, and these events the Christian must see as like one another, as if the whole history of matter and all the laws of physics and chemistry and even the Roman Empire were called into existence so that one lost man on a hill in Jerusalem would turn imperceptibly to his Maker, hidden in the flesh of a dying man, and say, "Lord, remember me when you come into your kingdom." And God saw the light, that it was good, and he separated the light from the darkness.

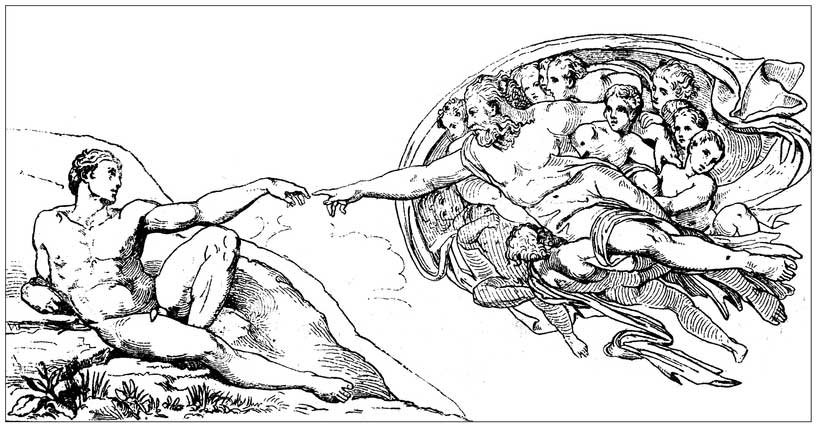

Of what dimension is a thought? We read that God made man in his image and likeness, and surely that reaches the greatness of the human person; we may think of Michelangelo's colossal Adam, reclining in grandeur, his eyes open, his head resting upon his shoulder as if he were waking from a dream, and his great hand relaxed, waiting for the touch of God. "You have made him little less than the angels," says the Psalmist. But he is also "dust," and maybe we are too ready to see in that insubstantiality an insult to Adam's dignity. Let us try to think otherwise. Only God could make dust divine: "And he breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and he became a living soul." What is that breath, that spark, that speck of dust, that seed? Man is too great for us to fathom, and the movements of his soul too small for us to penetrate. He, too, is a cloistered immensity, infinite riches in a little room.

To Teach a Child

So it is, and it has profound implications for our lives. What does it mean, then, for us to teach a child? Again it is helpful to posit an anti-parable. Mothers were bringing their small children forward for the master to bless them, and the master's disciples were ushering them in, but he said, "Do not suffer the little children to come unto me. They are not yet fully human. They serve no part of the kingdom I am building. They are clay before the clay is fired into bricks. I see beyond them." And he takes a puff on his cigar, imagining the dismay on the countenance of a foolish ally he is now ready to destroy.

Satan has no use for children as children. He has use for them only as inert stuff, or as precocious and perverse little adults, apparatchiks for working their parents over. Otherwise they are trivial—and the silly may as well teach them as the wise. And those who believe that education is for something big, like an empire, or the glass and concrete megaliths of clever barbarians, have no use for children either, treating them like cogs and camshafts and commissioners to be. So we see the children swallowed up into the mouth of a great educational machine, itself run as a cog in the machinery of an imperial technocratic state. In such places both the smallness of man and the greatness of man are lost. The seeds are lost. A gear is not a seed. A bureau is not a tree.

I must insist upon this. Whenever we turn away from the Holy of Holies, that God to whom the universe is as a grain of dust, and a grain of dust called "man" greater than the universe, we end up falling in adoration of what is merely big: and human beings, especially children, are sacrificed upon its altars.

Consider the very buildings where we send these children. We used to build schools that were relatively small, on a scale to meet and welcome the small people who would learn things there. The schools resembled homes or modest town halls or churches. They were not therefore puny and silly; their very cupolas and arches suggested that the small people were being invited into company with great and holy things. Why did we give that up? Because we are no longer sensitive to the priceless innocence of children; we think instead of efficiency and mass production and bureaucratic oil, and when that breeds anonymity and social dysfunction, when the most disturbed children find one another out and set down a sick school within the school, what do we do? The human thing, which would mean bringing schools back down to the scale of the child? No, we stock it with surveillance cameras and armed guards.

Does our failure to remember "the smallest of the seeds" distort not just the manner in which we teach children, but the content of education, too? What might be an educational analogue to that moment of conversion experienced by the heart opening itself to Christ? We can say at the outset what it cannot be. It cannot be like enlisting in a political program, dissolving oneself in some grand cause. It cannot be learning to "think globally," which is a contradiction in terms even for big people, and utterly absurd for children. But our schools now bristle with political programs. Think of the obvious contempt in which you must hold the human person, especially the child, if you believe that our highest aims are compassed by marching and waving signs with slogans on them. Not that political action as such is wicked. We must have political action; the meddlesome and the ambitious we will always have with us. But such big things and the big shots who promote them must be put in their strictly subordinate place.

Wonder the Key

Think of what happens the first time a child encounters a thing of surprising beauty. I recall the first time I ever heard one of the great hymns of the Church, the Pange Lingua of Thomas Aquinas. It was being sung by the small children of the local Catholic school as they processed behind the priest, who was taking the Blessed Sacrament to the repository on Holy Thursday, in the Mass of the Lord's Supper.

Why I had never heard that hymn before, I have no idea—or rather I do have an idea, but it is not a pleasant one. It is just that my church forgot what it is to wonder. It had replaced works of beauty with works of self-celebration and political posing. It had replaced the great and the small with the big and the trivial, with predictable loss of reverence for the secret and invisible presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

Wonder is the key; and wonder, because it is so close to both falling in love and falling in reverence, has no easy place in the modern school, or in the ordinary life of modern man. Suppose you have a boy commit to memory Emerson's famous poem about the Battle of Concord. "Here once the embattled farmers stood," he says, "And fired the shot heard round the world." Yet the poem is not boastful or garish. It is quiet. It ends in a short prayer that is proper for the solemn occasion: the raising of a stone to commemorate the battle, so many years later, when all trace of the conflict has vanished from the scene:

On this green bank, by this soft stream,

We set today a votive stone;

That memory may their deed redeem,

When, like our sires, our sons are gone.Spirit, that made those heroes dare

To die, and leave their children free,

Bid Time and Nature gently spare

The shaft we raise to them and thee.

And perhaps, just perhaps, the boy glimpses a whole world whose existence he had never suspected. It is a world in which the noblest deeds fall into oblivion; in which people are born and live and die, and their place knows them no more; and yet we want to remember, and behind both our memory and our forgetfulness stands the Spirit of God, who does not forget.

Entering the Mystery

That moment of wonder cannot be produced by industrial methods. It cannot be the object of bureaucratic control. It comes and goes, like the wind. The best we can do is to teach children to listen for that wind; and that requires a quiet smallness, and a reverent openness to the infinite. When the prophet Elijah was listening for God, he did not find him in the whirlwind or the earthquake or the political campaign or the school campaign urging young people to rouse up the greatness within them, and other such trivialities. God was in the still small voice.

That voice beckons the child into reality. If you are standing on the bridge at Concord, looking at the stream trickling away as if there never had been a battle, or even a breathing man upon earth, you might just enter into the mystery of human existence. We come from the great deep, as Tennyson says of King Arthur, and we go to the great deep; this is reality. If you experience for once the tremendous power of beauty in, say, that little space between the finger of God and the finger of Adam in Michelangelo's painting—the most electric moment of painterly silence in all of the history of art—you will sense, if only for a moment, that the world is more mysterious than any man can fathom. The man himself is greater than the universe; and is he not then greater than the political noise and banners of the day? Greater than the entertainment produced by an assembly line from assorted metallic hairs and nettles? Greater than restless dreams of power?

Or consider another moment of wonder. This is something the merely big cannot understand, because again it cannot be put to use for big and important projects. A man is dying.

I was at my father's side when he died, fully conscious, with all his children about him, touching him. I was at my mother-in-law's side when she breathed her last, having faded from consciousness several days before. What went on in my father's breaking heart in those last moments? He whispered to my mother that he loved her; it was the gift he gave at his latest moment, and it was so soft that we who were right there could not hear it. What went on in the secret recesses of my mother-in-law's memory when the last flutter of life fell still forever? We do not know. We may never know, until that day when we meet again in the presence of God, and perhaps not even then, because our life is hid with Christ in God, and in him there is no final depth to be sounded. You can come to know a Mr. Zeus, in the way that you can come to know any other shifty politician. That is, you recognize his habits, and you try to anticipate them. Knowing God is another matter entirely.

Infinite & Intimate

And here we come to the edge of the ocean. Isaac Newton once said that after all his scientific and mathematical discoveries, he felt still like a boy playing with pebbles on the shore. Again we mistake him if we think that he was referring only to his relative lack of knowledge. There is something quiet and deeply satisfying about that image of the boy with the pebbles. It should be so. Newton was an unorthodox Christian, but he believed deeply, and I think that he might have been closest to God when he felt like that boy, not despite the smallness, but because of it, delighting in it; for big important people do not play with pebbles, and that is why they do not discover God and the world he has made.

For God invites us to enter into a relationship with him that is infinite in all ways and intimate also, because he is, as Augustine says, more intimate to us than we are to ourselves. In him are united the movement of the heart, in love that conquers death, and the movement of the soul in wonder, as it beholds "the world in a grain of sand, / and heaven in a wild flower." The jaunty folk memory has Sir Isaac sitting under a tree when an apple strikes him on the head, and, presto!—he comes up with the idea of gravity, a force that explains the apple and the planet Jupiter likewise. I like to think that it was not an apple, but an apple seed, or a mustard seed, or something much smaller than that.

We should never forget these things. We teach children; we teach creatures made in the image of God. Which suggests to me a parable, if I may be so bold. "The Kingdom of God may be compared to a boy who was sitting upon a hill, looking at the sun. And when a great man came by, the boy smiled and said to him, 'Sit here upon my right hand, even you.' And he did." •

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor