Feature

The French Connection

The Many Parallels Between France’s Revolution & Today’s Anti-Christian Secularism

Would-be Marxists of the 1960s debated whether American society was then in a “pre-revolutionary” situation; by the time the smoke cleared, the answer was obviously in the negative, in the way Marxists understood revolution. The lasting effects of the sixties were cultural rather than political and economic, which caused the self-defined radicals—blinded rather than enlightened by their Marxism—to be slow in seeing them. The radicals did not overthrow the capitalist system or establish “participatory democracy,” but they did succeed in inflicting deep wounds on the nation’s moral and religious fiber. The effects of any cultural revolution are long-term, and in some ways the United States today may be on the verge of carrying that revolution to its completion.

History may indeed be repeating itself but, as always, as theme and variations, not as simple restatement. The situation today resembles not Russia prior to 1917 but France prior to 1789, and the history of the Catholic Church in early modern times offers striking parallels to the present.

Attacks from Without

Contrary to stereotype, Europe in the eighteenth century was by no means an irreligious culture. Most people were believers, the level of religious practice was high, and it was unthinkable that by the end of the century the Catholic Church in France would be all but destroyed.

But, through the centuries, governments had come to assume that the needs of the state took precedence. Monarchs wanted a free hand in dealing with religion, and the government of France was at pains to protect the liberties of the Gallican Church—the independence of the French Church from Rome. The pent-up spiritual energies that exploded in France after 1600 caused Cardinal Armand de Richelieu, himself personally devout, to seek to curb the religious zeal of others “for reasons of state.”

So religion began to be discredited, both legitimately and illegitimately, as a cause of division, persecution, and warfare. Although the early modern “religious wars” were not by any means solely about religion, the willingness of pious people to employ violence in support of their faith justified mistrust of their fervor, although that mistrust was also exploited for purposes that were sometimes even bloodier than the religious wars and more oppressive than the Inquisition.

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries came to be called the Age of Reason not (as in the stereotypical account) because reason had previously been ignored but because during that period the ancient Christian synthesis between faith and reason was rejected and reason alone became the acceptable guide to truth. The Enlightenment unfolded into a stance of suspicion or outright animosity towards almost all existing beliefs and institutions, of which Christianity was the chief.

Also contrary to stereotype, the philosophes—the French intellectuals of the eighteenth century—sought not diversity of opinion but the replacement of one kind of intellectual unity by another. Feeling themselves to be in the ascendancy, they did not have to confront their opponents fairly, because, in their minds, certain ideas had been so thoroughly discredited as to be held only by the ignorant and deluded, and to take such ideas seriously would be to yield ground in the continuous war of ideas. Thus, perhaps the philosophes’ most effective weapon was the subtle censorship of fashion, the ability to make orthodoxy seem outmoded and ridiculous. Whatever else they were, the philosophes were masters of condescension and ridicule.

Alongside the condemnation of religion as a cause of hatred, a heightened historical consciousness—drawing on the work of Christians like Abbe Mabillon, Richard Simon, and Pierre Bayle—attempted to discredit Christianity in its very origins. Edward Gibbon endeavored to show in massive detail that the triumph of the Church had been the triumph of ignorance.

Others looked beyond Europe. Unfamiliar lands were being explored, and skeptics used travel accounts—factual or fictional—to deny Christianity’s universality, positing the existence of communities that were idyllic because they were uncorrupted by Christianity, especially by its repressive sexual morality.

Complacency Within

The struggle of the eighteenth century was not, however, simply a conflict between believers and skeptics. Many Christians of the period were complacent about the threat the philosophes posed, whereas the latter were driven by passionate conviction and an urgent sense of mission. Voltaire dedicated his book on Mohammed to Pope Benedict XIV, who at first did not recognize that Voltaire’s ridicule of Muslim beliefs as fraudulent was a way of insinuating the same thing about Christianity.

In many ways the balance was held by “enlightened” Christians, some of whom were more than merely complacent, accepting Christian doctrine only insofar as it could be made to fit with enlightened ideas. Some Christians searched for a religion that transcended theological differences and was based on reason and accessible to everyone—an enlightened Deism that excluded the possibility of divine revelation. Human happiness, understood in a worldly sense, became the highest moral good, replacing the salvation of souls.

Besides rational skepticism, the Church was also threatened by a new kind of religion that repudiated Christianity while retaining the religious instinct. Jean-Jacques Rousseau, born a Calvinist and briefly a Catholic, repudiated the idea of sin and blamed society for all moral evil, extolling primitive existence and “natural man,” untrammeled by the conventions of civilization, as the most virtuous and authentic mode of human life, a teaching he found in Jesus’ warnings against worldliness.

Jansenism & Its Complications

Jansenism, with its highly pessimistic view of human nature and its puritanical moral teachings, was for two centuries the most influential and tenacious modern Catholic heresy. It was inimical to the Enlightenment spirit as well, but by the unpredictable vagaries of history, its fate came to be intertwined with that of its enlightened despisers.

The Jesuits were the great adversaries of both the Jansenists and the philosophes. Against Jansenism they taught the existence of natural virtues that made moral restraint and balance possible, thereby justifying, albeit cautiously, worldly pleasures like dancing and the theatre. For this, the Jansenists accused them of catering to the lax consciences of the aristocracy.

Because of its views about grace and free will, Jansenism was repeatedly condemned—by the Sorbonne, by a majority of the French bishops, by several popes, even by the king. Partly because of these condemnations, an animus against authority came to characterize Jansenist ecclesiology, and its underground press mounted an effective attack on both civil and ecclesiastical authorities.

The Parlement of Paris was France’s highest law court, and in the eighteenth century it was the only institution capable of resisting the king. Few people in the upper middle class, from whose ranks Parlementarians were drawn, had sympathy with Jansenist theology, but the Parlement as a body tended towards Gallicanism and championed the Jansenist cause for that reason.

The situation was bewilderingly complex. Most bishops were simultaneously Gallican royalists and anti-Jansenists, something made possible because, while the Jansenists had been condemned by the pope, they had also been condemned by the king.

The issue exploded over the policy of some bishops of denying the sacraments to those who would not affirm the condemnation of Jansenism. Those affected appealed to the Parlement, which responded by arresting priests, on the grounds that the denial of the sacraments was a violation of civil rights and a slander on those affected. As the battle escalated, the Parlement steadily increased its claims to authority over church affairs.

France was by no means the only place where papal authority was under attack. A German bishop writing under the name Febronius published an influential treatise making the pope merely a kind of presiding officer in the Church and holding that diocesan bishops received their authority directly from Christ. Meanwhile, many of the lower clergy resented the authority of the bishops, a stance that was justified by one Edmond Richer, who claimed that parish priests were the direct successors of the seventy-two disciples sent out by Christ and that therefore they had authority independent of their bishops. This theory was held by both Jansenist and anti-Jansenist priests.

The Jansenists were thus allied with the Parlement in attempting to check royal authority, with Gallicanism in rejecting much of papal authority, and with Richerism in undermining episcopal authority.

Although the Jansenists were the most devout of Christians, their hostility to the Jesuits aided the triumph of unbelief, since the Jesuits were by far the most effective defenders of orthodoxy.

The fate of the Jesuits came to a head in a seemingly rather trivial incident that had nothing to do with theology. Their involvement in the Caribbean trade led to their being sued by various creditors, which gave the Parlement an opportunity to subject them to official scrutiny and eventually to urge their expulsion from France as enemies of the crown. Virtually all the bishops opposed this move, but Louis XV reluctantly agreed, because he needed the Parlement’s help with his chronic financial troubles.

Revolution & De-Christianization

When the French Revolution began, it was partly under the leadership of a bishop—Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord, who was a religious skeptic—and two priests—Henri Gregoire, who was of Jansenist sympathies, and Emmanuel Sieyes. A substantial number of the lower clergy in the First Estate favored reform.

In July 1790, the Civil Constitution of the Clergy was passed, and it embodied most of the things that enlightened Catholics wanted. Priests had to swear that they had no loyalty higher than France; bishops and priests were to be elected by laymen, including non-Catholics, and were subject to governmental supervision; parish and diocesan maps were redrawn to coincide with the units of civil government; and a large number of dioceses were suppressed.

Monasteries were abolished and, although nuns were not required to take the oath, their convents were officially disbanded. There was a concerted campaign against clerical celibacy, partly on the grounds that priests had an obligation to produce children for the Republic, partly because celibacy was recognized as a major source of the priestly charism. Education was secularized, so there would be no danger of inculcating “counter-revolutionary” ideas in the young.

The Civil Constitution split the nation, forcing people to choose between the Revolution and their religious loyalties. Half the clergy refused to take the oath and were deprived of their offices, many of them, including most bishops, then fleeing the country. The other half took the oath, and a new group of “constitutional bishops” was named.

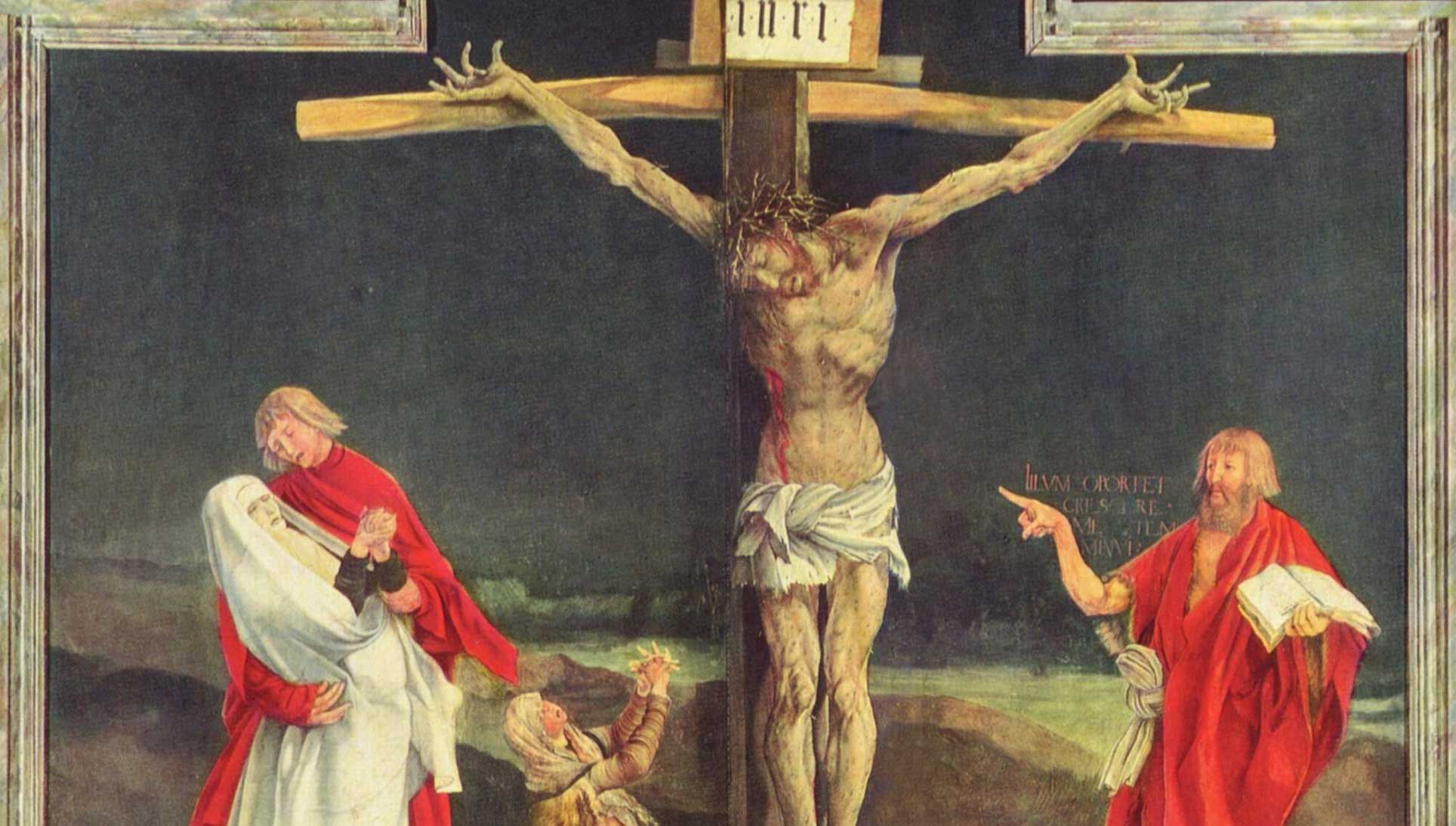

But during the Reign of Terror (1793–1794) all churches were closed or converted to secular uses, thousands went to the guillotine, and even clergy who had taken the oath were forbidden to exercise their ministries. The Revolution attempted to establish a new religion. Its calendar began with the year One; Sundays could not be observed in any special way; saints’ names were abolished, especially in favor of classical pagan names like Brutus; and new holy days, like the feast of Reason, were decreed.

Compulsory optimism was at the heart of this new creed, as the Revolution promised the achievement of a perfect society and a perfect humanity, rejecting the doctrine of Original Sin as one of Christianity’s most pernicious errors. The gospel was said to teach the social equality of all men.

As has usually been the case throughout history, in the end it was martyrdom, not diplomacy, that saved the Church. The blood of those who perished indeed proved to be the seed of rebirth.

Unfinished Agenda

But it is a melancholy fact that the de-Christianization campaign, after being heroically resisted in the 1790s, is succeeding in the twenty-first century through voluntary surrender by nominal believers, to the point where the European Union now refuses to acknowledge its historical Christian roots and religion has apparently ceased to be a vibrant reality even in the private lives of most Europeans.

For the most part, the British Enlightenment, unlike the French, was not anti-Christian, so religious movements (Methodism, the Second Great Awakening) of the time were equally influential with secular ones. But this means that, for modern secularist Americans, the agenda of the anti-religious Enlightenment remains unfinished. Thus, to a degree unprecedented in American history, there now exists an anti-religious animosity similar in many ways to that of the eighteenth-century philosophes. Also as inthe eighteenth century, it is linked to dissidence within the Church.

The sleeping giant of Fundamentalism, partly awakened by the cultural revolution of the 1960s, is now condemned as a cause of division and strife, as were the Catholic devots four centuries ago, because it disturbs secularists’ comfortable assumption that religion is a dying phenomenon.

While religious persecution and religious wars have long ceased in the West, and while modern history has repeatedly demonstrated that secular creeds like Nationalism, Fascism, and Communism are far more deadly than religion, it is religion that continues to raise alarms. As the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist wryly observed, even ordinary civic disagreements, such as public prayer or public funding of religious schools, have been treated by the Supreme Court as the equivalent of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre.

The real issue now, as during the Enlightenment, is ultimately not the perversion of religion to violence but something deeper. Christianity is feared not for what it does but merely for the fact that it exists.

The “Religious Right” is condemned as intolerant, even fascist, not because it seeks to coerce belief but because it refuses to ratify the sexual revolution of the 1960s and continues to recognize that Americans are a religious people. The pro-life movement is treated as an illegitimate “intrusion” of religion into an area where the issues were supposedly settled long ago by enlightened despots called judges. In recent decades there has been renewed warfare between religion and science, caused partly by religious excesses but even more by scientists and philosophers determined to use science to discredit belief.

Modern Philosophes

It is these aggressive skeptics, not the theologians, who now wield the power of censorship, causing courts to find the teaching of “creationism” and “intelligent design” to be violations of the Constitution. Somehow freedom of thought is said to require the suppression of unwelcome ideas.

The classical liberal ideal of free expression is now being repealed in some places. In Canada and France, for example, those who utter “hate speech” by expressing disapproval of homosexuality or by offending religious minorities are now subject to criminal prosecution. Freedom of expression is still protected by law in the United States, but the most notable exceptions are precisely those centers of self-conscious enlightenment called universities; here, censorship of ideas through “speech codes” and other means is not uncommon, and one can get a preview of what modern philosophes envision for the larger society.

Modern philosophes, like those of the Enlightenment, regard themselves as having gained an intellectual ascendancy that must not be lost. While the eighteenth-century struggle was to free education from religious control, now it is the very existence of religious education that has been put in question.

As in the Enlightenment, perhaps the most effective form of censorship is fashion—the tyranny of condescension and ridicule, a shortcut to victory that removes the obligation to offer serious argument. Where religion is concerned, many modern secularists betray an intellectual flabbiness induced by habitual lack of exercise.

The Enlightenment attempt to discredit Christianity in three ways—as the incubator of hatred and violence, as based on a false understanding of its own origins, and as merely one manifestation of the natural human religious instinct—is now being reprised.

Besides the systematic attempts to discredit the historical reliability of the Scriptures, the ancient movement loosely called Gnosticism has been transformed from the chief heresy of the first two centuries into the most authentic form of early Christianity, while orthodoxy has been declared a distortion of it. During the Enlightenment, Christianity’s critics were divided on whether to dismiss Jesus as a deluded fraud or to claim him as their own. Today, the second strategy is almost universally favored—the most lethal blow against Christianity is to capture its founder and demonstrate that for two thousand years his followers have betrayed his teachings.

Enlightenment Inheritance

The French Revolution’s attempts to establish a new religion that repudiated Christianity while retaining the religious instinct has its parallel today in the various New Age movements, to which even professed Christians are attracted. Behind the posturings of Wicca and goddess-worship lies Rousseau’s sinless “natural man,” reincarnated in “creation spirituality” and other theologies that offer people only “affirmation” and never make demands.

Christianity’s modern critics wield compulsory “multiculturalism” as one of their most potent weapons, forbidding criticism of other faiths while subjecting Christianity itself to the most severe scrutiny, permitting condemnations of Muslim terrorism only if Christian Fundamentalists are condemned in the same breath.

As in the Enlightenment, the balance is now held by what are today called “liberal” Christians. The essence of modern religious liberalism is accommodation to the Enlightenment by a series of strategic retreats (miracles, Jesus’ bodily resurrection), each of which is thought to protect the core of the faith, until finally scarcely any core survives.

While religious liberals extol “open-mindedness,” in reality they are in thrall to the secular dogmas of the modern Enlightenment, and they earnestly scan the horizon to discern their next assignment (“The world sets the agenda for the church”). Liberal Christianity has no quarrel with the role it has been assigned by the dominant enlightened culture, which can see no purpose for religion except as a support for various secular causes. While gladly assuming an obligation to question the teachings of historical Christianity, liberal Christians tolerate no skepticism towards the endless succession of such causes—the welfare state in its various forms, feminism, the sexual revolution, environmentalism.

Modern religious liberalism understands Christianity in ways that are a direct inheritance from the Enlightenment and even from the French Revolution: the promise of human happiness, the achievement of a perfect society, the social equality of all men. Hence, the doctrine of Original Sin is deemed one of Christianity’s most pernicious errors.

Like Enlightenment Deists, liberal Christians seek a religion that transcends theological differences, so those who insist on the unique truth of Christianity are declared to be dangerous bigots, fomenters of division and strife. The “fanatics” condemned by the French Revolution are today’s Fundamentalists.

In many ways Jansenism was the equivalent of that Fundamentalism in pre-revolutionary France. But the trajectory of its history is similar to that of modern liberal Christianity. And today’s Jesuits are, to a great extent, closer in spirit to the philosophes than to their own eighteenth-century predecessors. (A request from Pope John Paul II that they undertake an intellectual confrontation with atheism was ignored.)

An Increasingly Tight Noose

Throughout the long history of Christianity, not only the defenders of orthodoxy but also the advocates of change have often turned to the state for support. The Civil Constitution of the Clergy was the culmination of a decades-long process in which political power was used to achieve religious goals.

Since liberal Christians have internalized the values of the modern Enlightenment, secular attacks on Christianity coincide with religious liberals’ programs for remaking their own faith. What is charged against Christians by the most militant secularists is no more severe than what is charged by many members of their own churches.

The Church is most vulnerable when it fails to govern itself. In eighteenth-century France, the trivial matter of the Jesuits’ ill-advised involvement in the Caribbean trade led to the suppression of that order. Today, the issue is the far more serious matter of the Catholic bishops’ inexplicable failure to protect the faithful from sexually predatory priests.

Unlike in the French Revolution, traditional believers in modern America will probably not be persecuted in a physical way, but they find themselves in an increasingly tight noose that severely constricts their ability to live their faith. A respectable body of academic opinion considers freedom of religion a luxury the nation cannot afford; thus, there have been serious proposals to curtail the rights of schools, churches, and parents to propagate “pernicious” ideas, and even proposals to exclude religious believers from holding public office (see my “The Enemies of Religious Liberty” in First Things, February 2004).

The “red state/blue state” pattern in American politics demonstrates the precarious way in which religious freedom depends on election returns. But in the long run it may not matter. Liberals are more than willing to transfer sovereignty to international institutions that have the authority to override the practices of “backward” societies. Modern religious liberals can justify such use of power because they see the state, when properly ordered, as embodying the highest moral values and as possessing the authority to correct those people and institutions that do not fully share its vision.

Worship of the Welfare State

Liberals’ true church is the enlightened welfare state that takes responsibility for both the material and spiritual well-being of its citizens. Liberal Christians, whatever their denomination, in fact hold their primary membership in that church. Liberal humanitarianism is a Christian heresy in the classical sense of exalting one Christian doctrine—here love of neighbor—in such a way as to crowd out all the others. As in the Enlightenment, a worldly ideal of human happiness replaces obedience to the divine will in the hope of eternal salvation.

The welfare state is a religion in that it rests on faith. Its promises cannot be judged by history but must be reaffirmed over and over again as a self-evident, transcendent truth. Thus, for Christians to vote against President Obama and his promises is a wicked act.

In the eighteenth century, Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II suppressed the monastic orders as “useless,” because they witnessed to a higher Kingdom, which detracted from his own. He tolerated nuns who nursed the sick, and he tolerated religious schools only as long as they were overseen by the state. The modern welfare state also permits agencies of religious charity, such as hospitals, and it reluctantly (and perhaps only temporarily) tolerates religious schools. But those charities are increasingly being drawn into the secular net: receiving funds far beyond what the churches themselves could provide they are in turn being subjected to innumerable kinds of government regulations.

The liberal idea of “welfare” also continually expands, in accord with continually evolving, wholly secular concepts of the good life. Contraceptives must be provided, especially to young people, who are expected to “explore their sexuality”; and abortion must be provided for those who are insufficiently cautious. Avant-garde states facilitate suicide, euthanasia, and same-sex “marriage.”

Already religious agencies in some states are required to facilitate homosexual adoptions, and medical personnel are threatened with the rescinding of “conscience clauses,” which currently allow them to refuse to perform or assist with procedures they deem immoral. In time, courts will tell the churches that they must ordain women, and clergy will be ordered to officiate at homosexual “marriages.” Religious agencies, including schools, will be closely monitored for violations of liberal dogmas. Even family size may be limited by law.

The liberal state seeks to transfer moral and religious authority from the Church to itself, defining traditional morality as retrograde and asking church members to recognize their political leaders as their spiritual guides as well (e.g., Catholics would look to Nancy Pelosi rather than the Catholic bishops).

No Sure Safety

During the eighteenth century, some Catholics (both the self-consciously “enlightened” and the defiantly unenlightened Jansenists) welcomed the restrictions the state placed on the Church, since those restrictions supported their own ecclesiastical agenda. Today, liberal Christians are fervent supporters of the welfare state, and they find Fundamentalists a greater threat to society than the secularists.

Politically, the principal difference between liberals and conservatives is the former’s faith in the welfare state’s promise to achieve a truly just society, the secular equivalent of the Kingdom, and the latter’s conviction that such a dream is both illusory and dangerous. Varying degrees of utopianism are endemic to liberalism’s project, something that gives it a sense of urgency, whereas, at its best, conservatism often functions merely negatively, attempting to stop the liberal juggernaut.

Sooner or later, draconian coercion will be needed to force reluctant people to accept the planners’ idea of the perfect society. As even liberal Christians may one day discover, it is not enough merely to be enlightened and in tune with history. During the Reign of Terror, after having given good service to the Revolution, eight “constitutional bishops” perished on the guillotine.

James Hitchcock is Professor emeritus of History at St. Louis University in St. Louis. He and his late wife Helen have four daughters. His most recent book is the two-volume work, The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life (Princeton University Press, 2004). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor