Heaven Knows by Anthony Esolen

Heaven Knows

Christian Irony & the secrets of Kings & Gods

by Anthony Esolen

The gods know what men do not. They may hoard up their knowledge to punish

the wicked, or to bring innocent men to destruction, or they may parcel it

out, little by little, to teach men the hard lessons of humility and wisdom.

An example from ancient Greece will illustrate the point.

One day a young man fell into a quarrel at a three-way intersection on the

road to Thebes, and killed the man in the chariot who had struck him and tried

to hustle him aside. As Sophocles’ King Oedipus opens, this same passionate

Oedipus, who freed the Thebans by solving the riddle of their nemesis the Sphinx,

now plies his considerable power of mind and his almost unruly energy to solve

a new riddle: Why are his beloved Thebans dying of the plague?

It is his responsibility to bring them salvation, and he groans under the

burden. So he addresses the people who come pleading for his help:

And while you suffer, none suffers more than I.

You have your several griefs, each for himself;

But my heart bears the weight of my own, and yours

And all my people’s sorrows. I am not asleep.

I weep; and walk through endless ways of thought.

He tells them that he has done “the only thing that promised hope”:

sent his kinsman Creon to ask the Delphic oracle what to do.

Let us pause to note the king’s tragic virtue. Were it not for his

intellectual acuity and restlessness, and his care for the people, the tragedy

would not unfold. Oedipus would never learn that he himself caused the plague.

Nor should we simplify the moral problem—that a man can be destroyed

by his virtue—by saying that Oedipus esteems the human intellect too

highly, and refuses to submit to the wisdom of the gods. He has admitted being

at a loss, and that is why he must appeal to Apollo at Delphi.

Oedipus’s Curse

When Creon returns with word that the plague is a punishment for the unavenged

murder of the late King Laius, Oedipus determines to ferret out the murderer.

We in the audience know—we are Greeks, and have heard the tale before—that

Oedipus is himself the killer.

Thus, when he delivers his first proclamation to the people, we are aware

of the trap that will catch him by his own words. “The unknown murderer,” he

says, shall “wear the brand of shame” forever, driven from the

city, friendless until death. Nor does he exempt himself from the curse:

If, with my knowledge, house or hearth of mine

Receive the guilty man, upon my head

Lie all the curses I have laid on others.

We know what the gods know and what Oedipus does not know, and we also know

that, were we in Oedipus’s place, we would know as little as he. Man

is a marvel, says Sophocles, taming the waves and furrowing the land with wheat,

tracking the paths of the stars and building his gleaming cities of marble,

but eternal laws bind us, and the gods who know the future and seldom tell

it will deal out their justice as they please, and not as we determine.

Sophocles’ play is a spider web of dramatic irony, of the dreadful

weaving of gods unseen. Were it not for the equivocations of the oracle at

Delphi (a notoriously anti-democratic oracle, hostile to Sophocles’ Athens),

there would have been no tragedy. The gods begin by playing with, meddling

with, the incomplete knowledge of men. They seem to enlighten, yet bring darkness.

For Laius and his wife Jocasta had learned from Delphi that the son she bore

would kill his father and marry his mother. To avert this unspeakable wickedness,

they committed wickedness of their own, laming the child (hence his name Oedipus,

or “Swollenfoot”) and instructing a trusted servant to expose him

in the mountains nearby.

What the Gods Will Do

Such exposure was thought of as returning the child to the gods—a perilous

chance, it seems, when the gods are malign, leading you on to commit the deed

for which they will crush you. But Oedipus did not die. He was taken up by

a shepherd and brought to Corinth, where he was adopted into the home of Polybus

and Merope, whom he took for his father and mother.

Yet people will talk. Young Oedipus, hearing it whispered that those good

people were not his parents, went in person to Delphi—as always, impetuous

to know. The oracle, as oracles will, did not reply to the question he asked.

Instead, the priestess informed Oedipus that he would kill his father and marry

his mother. Horrified by the prospect of this sin, Oedipus leaves Corinth.

If he is to be blamed for thinking he could avert the evil, he is also to

be credited with wanting so much to avert it that he would sentence himself

to exile. However we judge his flight, it is clear that the gods have put him

in the way of the sin: Had he been less pious, less desirous to know the truth,

and less courageous, he never would have left Corinth, and therefore never

would have sinned.

The gods have given him what he thinks is reliable knowledge, knowing that

he would misinterpret it and believe he knew what he did not know. We in the

audience know this, and watch the plot unfold, and know that the gods may do

the same to us.

In a world ruled by such gods, the sharpest tool man possesses, language

itself—without which he could not build a community—turns in his

own hand to cut him. Oedipus has heard from the oracle, but wants to hear more,

so he summons the old seer Tiresias. That prophet knows what Oedipus does not

know, but in his desire to spare him (no matter for the plague that devastates

the city) he will not speak.

Oedipus interprets the silence plausibly enough, accusing Tiresias of wanting

to protect himself from suspicion:

I tell you I believe you had a hand

In plotting, and all but doing, this very act.

If you had eyes to see with, I would have said

Your hand, and yours alone, had done it all.

To which the seer replies with the most devastating line in the play:

You would so? Then hear this: upon your head

Is the ban your lips have uttered—from this day forth

Never to speak to me or any here.

You are the cursed polluter of this land.

The Gods’ Agent

“You are the man!” Oedipus will not believe it. Why should he?

Tiresias has given no reason. The accusation only enrages the king, drawing

from his lips the condemnations that will come down upon him when the truth,

the how and where and why of it, is finally revealed.

We watch in amazement and comprehending horror as the ruler of Thebes does

what we know we might do, denying what he cannot understand, in his ever greater

stridency pressing against the truth he cannot help but suspect, the truth

that cannot be but is. Indeed, Oedipus learns nothing from his contentious

meeting with Tiresias, and is meant to learn nothing. Instead, the clue leads

him to pursue false suppositions, as for instance that Tiresias has connived

with Creon to steal the throne.

The man is being crushed by the gods.

There is no escape. When, finally, Oedipus learns how he has slain his father

and “sowed the field” of his mother, he becomes both agent and

subject of the gods’ irony: He puts out his eyes, the egg-like organs

that refer symbolically to the testicles, his instruments for the great crime

against nature.

The moral that the chorus draws from the terrible finale is one of resignation,

even despair. The lofty will fall, not necessarily because they are proud (though

they usually are), but because they are lofty. Best to keep to the unobtrusive

middle; best to know when to duck.

We live in relative ignorance, and do not even know, as Oedipus certainly

did not, whether we shall escape this twilight life with something like happiness.

Only the end makes us sure: and at that end, we do not rejoice but breathe

a sigh of relief. Oedipus, they say, was once the greatest and wisest of men,

but

Behold, what a full tide of misfortune swept over his head.

Then learn that mortal man must always look to his ending,

And none can be called happy until that day when he carries

His happiness down to the grave in peace.

Oedipus & David

Now compare the Oedipus story with this account from the Old Testament, told

in 2 Samuel. David, king of Israel, is a married man, married once, and not

happily, to Michal, daughter of the late King Saul, and then again to Abigail,

a woman who had assisted him when he fled Saul’s wrath. And there were

at least two others.

Then one evening David, rich in wives, “arose from off his bed, and

walked upon the roof of the king’s house: and from the roof he saw a

woman washing herself; and the woman was very beautiful to look on.” He

learns that she is Bathsheba, wife of his loyal soldier, Uriah the Hittite.

He sends for her, and lies with her, “for she was purified from her uncleanness,” that

is to say, she was past the time of her menstrual period.

The inspired author need not mention that neither she nor David is purified

of the uncleanness of adultery, and the sly detail leads us to suspect that

the good and clean time for a husband to have relations with his wife is not

the best time for David to have relations with Bathsheba. For “the woman

conceived, and sent and told David, and said, I am with child.”

Now David finds himself in difficulties. He knows a secret, and thinks he

can keep it hidden. He wants Uriah to lie with Bathsheba, that the child already

conceived may be passed off as Uriah’s own, given the vagaries of gestation

and reckoning the calendar.

He summons Uriah from the battlefield, asking him pertinent (but to David

quite unimportant) questions about the war. Then he commands him to go home

and “wash his feet,” a euphemism for bathing the genitals, as prelude

to more delightful battle with his wife. David even sends a rich meal to his

house, hoping that a full belly will set him to it.

That should have been enough. But he does not reckon on Uriah’s great

loyalty: The soldier knows his duty, and will not go home. “The ark,

and Israel, and Judah, abide in tents; and my lord Joab, and the servants of

my lord, are encamped in the open fields; shall I then go into mine house,

to eat and drink, and to lie with my wife? As thou livest, and as thy soul

liveth, I will not do this thing.”

Royal Shame

The hearer of these words in the synagogue must consider the irony. Here

we have David, who danced for joy as he brought the sacred Ark of the Covenant

into Jerusalem. But David has forgotten about that covenant.

Uriah has not forgotten—and he is Uriah the Hittite, an alien, one

who has chosen to worship the God of Israel and to fight as a soldier for Israel’s

king. He is to be loved as an Israelite, for they themselves “were strangers

in the land of Egypt,” says the Lord, and this stranger is moreover one

who, like David’s own great-grandmother Ruth, has piously united himself

with God and God’s people.

David’s hand is forced, or so he thinks. He’s given Uriah a decent

chance; now there is nothing to do but order him killed in battle. His letter

to his general Joab leaves, in politic fashion, the means to Joab.

That general—who made a virtue of placing political considerations

above piety, even though he knew right from wrong—obeys. But obedience

exacts a price, taking the lives of others besides Uriah: for Joab has had

to engage in a “blunder” to expose him. Joab knows that David will

understand.

Thus Joab instructs the messenger who will take the news to David: “If

so be that the king’s wrath arise, and he say unto thee, Wherefore approached

ye so nigh unto the city when ye did fight? Knew ye not that they would shoot

from the wall? Who smote Abimelech the son of Jerubbesheth? Did not a woman

cast a piece of a millstone upon him from the wall, that he died in Thebez?

Why went ye nigh the wall? Then say thou, Thy servant Uriah the Hittite is

dead also.”

Joab washes his hands of the blame. Yet he wants David to know that the action

was shameful; so shameful that one Abimelech must die by a woman’s hand,

all so that David’s “servant”—fine word, “servant”—would

never return alive.

Intimate Absence

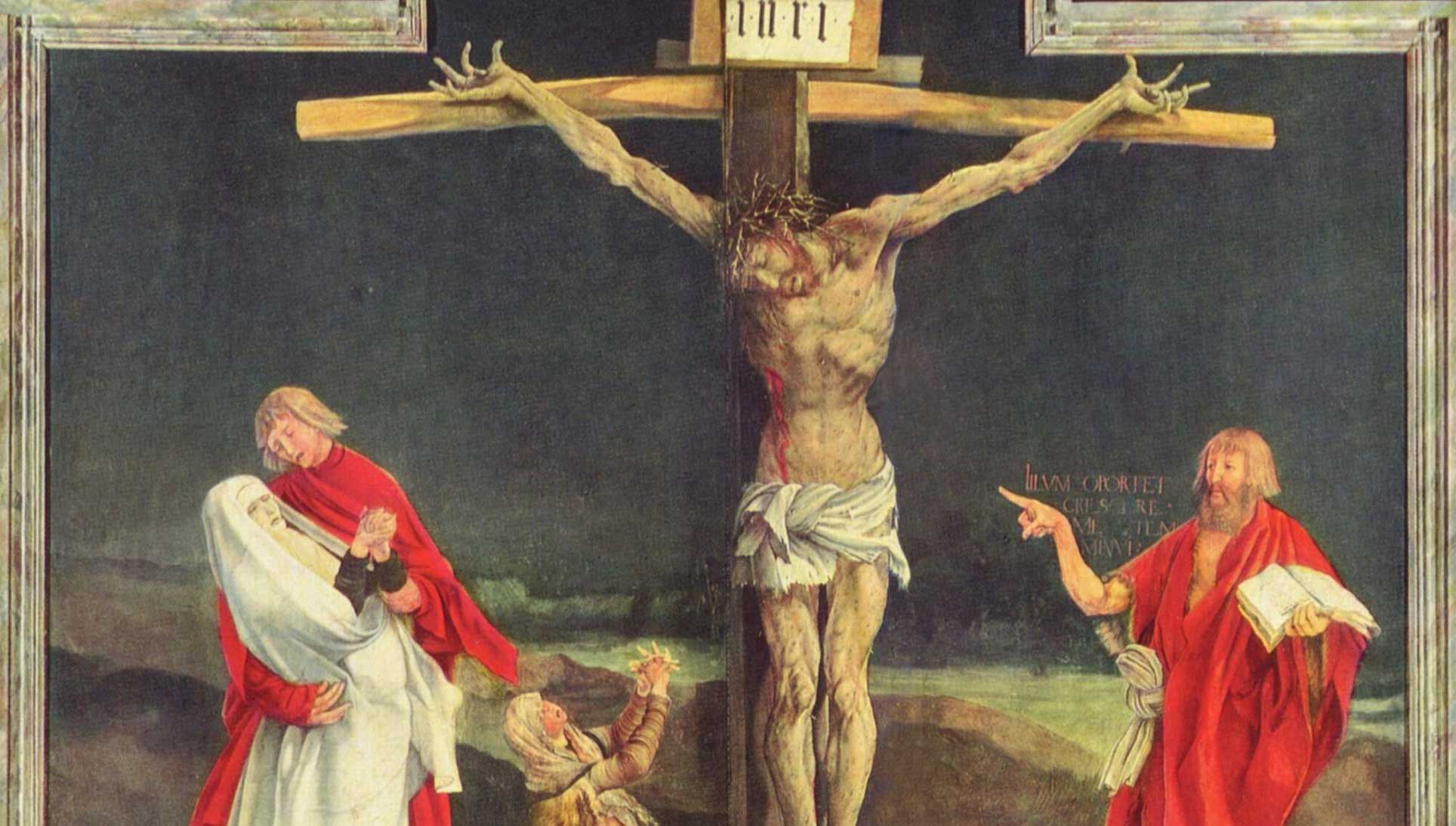

By comparison with the gods of the Greek play, the God of Israel seems to

have kept free of the scene. He does not meddle, nor use oracular chicanery

to elicit the wickedness he will punish. David’s sin has its birth in

David’s mind alone.

But in another sense, God is all the more intimately involved by his apparent

absence. Uriah’s reference to the ark reveals God’s presence: That

precious box, so humble that David thought it unworthy, was the dwelling place

of the Lord among his people.

The Lord is near, as David of all people ought to know. He and Joab know

what the messenger does not, but the Lord knows all, and will bring it to light.

The Greek gods know many things that men do not; they do not know everything;

they, too, submit to a mysterious Fate. One of the things they do not know,

or do not care to know, is the human heart. But the Lord does know the heart,

because there is the ark or temple where the Lord wishes to dwell, pleased

with the only sacrifice that means anything: the burnt offerings of love. So

the Lord sends a messenger to David.

The king does not send for the prophet; the prophet comes to the king. Tiresias

speaks in riddles almost perversely designed to enrage Oedipus and check his

understanding; Nathan speaks in a parable designed to capture the heart of

David before he is aware. We who are aware watch as the scene builds to its

climactic irony. Once upon a time, says Nathan, there were two men, one rich,

and the other poor. The rich man had wealth abounding, but all the poor man

had was one little lamb, the darling of his family, that ate from his own hand

and drank from his cup, and was as a daughter to him. But then “there

came a traveler unto the rich man, and he spared to take of his own flock and

of his own herd, to dress for the wayfaring man that was come unto him; but

took the poor man’s lamb, and dressed it for the man that was come to

him.”

Hearing this, David flares up in righteous anger: “As the Lord liveth,

the man that hath done this thing shall surely die: And he shall restore the

lamb fourfold, because he did this thing, and because he had no pity.”

But the seer Nathan turns to him and says, “Thou art the man.”

The Key Moment

“You are the man!” That accusation again—with a difference.

The parable has summoned David’s sympathies. He feels in his heart the

betrayal of the poor man, what he did not feel in Uriah’s case, as he

shuffled and connived. The vision he is granted, by the mercy of God, and by

God’s justice, which does not veer from his mercy, is meant to convict

him, and, by convicting him, to redeem him.

Nathan delivers a terrible prophecy of punishment to come, duly levied upon

David’s offspring, in that David had violated the womb of another man’s

wife. War shall fall upon David’s house, and the child conceived by Bathsheba

shall die.

What David did in secret, the Lord will fittingly do in the open, to David’s

shame before all the people. But even as he hears the punishment, David is

struck to the heart, not urging excuse, but saying simply, “I have sinned

against the Lord.”

That is the key moment. God works to bring David to life again; he is God

of the living, not the dead. Nathan replies at once: “The Lord also hath

put away thy sin; thou shalt not die.”

And David does penance, fasting, lying prostrate upon the earth, praying

to no avail that the Lord will alter his punishment and let his child live.

The half-understanding counselors see this and try to advise the king to be

reasonable, but he, wiser than they, refuses.

Then the child dies, and David lifts himself from the ground and bathes and

changes his clothes, to the astonishment of those same counselors, who still

do not see. Why mourn now? says David. What good will that do?

The king’s trust is once again like a child’s. He has submitted

to the Lord. And so far from believing that Bathsheba is unclean territory,

he understands not only his sin but the Lord’s forgiveness. After night

comes the morning: “And David comforted Bathsheba his wife, and went

in unto her, and lay with her; and she bare a son, and he called his name Solomon:

and the Lord loved him.”

How strange that the son of the foolish adulterers (and one of them a murderer

as well) should become the next king of Israel, proverbial for his wisdom!

But Solomon is the son not of the adultery, but of the repentance and the forgiveness.

He is the son of the new knowledge, not simply that mankind is nothing before

the gods, but that man who is nothing before God is, by the grace of God, as

the Psalmist says, “a little lower than the angels,” crowned with

glory and honor. Nathan ratifies the event, for David sends for that good prophet,

who looks upon the baby and “called his name Jedidiah [beloved of the

Lord].”

That story of David and Bathsheba reveals the workings of a God whose ways

are not our ways, whose thoughts are not our thoughts, but who makes us to

walk in his ways, and to be fulfilled in the intellectual vision of his glory.

If it is not irreverent to say so, he is a God who swindles man into his restoration.

He dupes man into truth. He becomes flesh, to raise man to himself.

Already Found Out

Indeed the gods know what men do not. The sinner makes much of his intellect

(Oedipus) or his cunning (David), only to find with a shock that he has already

been found out, and that not only does he know less than he thought he did,

but the truth is other than what he had suspected.

In both cases the sinner comes to a humiliating (for Oedipus, also horrifying)

knowledge of who he is, and how small he is before the divine. In both, future

generations will suffer the punishment also: Israel will be divided into two

kingdoms, reflecting the division foretold for David’s family; and Thebes

will fall to civil war when each of the incest-born sons of Oedipus attempts

to oust the other.

Yet Oedipus is the archetypal tragic hero, while David is celebrated as a

great king.

David’s sins and unhappy old age could never, for the Jewish people

and their prophets, efface his glory as Israel’s greatest ruler and the

progenitor of the Messiah.

Why the divergence? One reason is that the dramatic reversal instructs David

in a way it cannot instruct Oedipus. The sinner gains knowledge of himself,

true. But he also gains knowledge of God, and of God not as an external and

mystifying will, but as a person, a Being to whom one can pray, before whom

one can dance, before whom one can lie prostrate upon the earth. He is a God

who reveals himself because he wishes to be known.

So for Jews and Christians there is an added dimension to the irony of incomplete

knowledge, a liberating depth, where otherwise all would have been flat confinement.

A single act of love from the heart of the Almighty explodes the tense yet

static confrontation between the classical heroes and the gods.

For no matter how heroic or pious the man was, he could never know more about

the gods than was already given him to know: They were immortal, powerful,

beautiful, ruthless. Greek philosophy serves rather to highlight what man cannot

know for certain about the gods than what he can know or even suppose with

a fair probability.

Where could that pagan religion lead, if not to despair? By the time of the

Roman poet Lucretius (ca. 60 B.C., four centuries after Sophocles), many looked

to be liberated by admitting defeat.

Everyone supposes that the gods exist, says Lucretius in On the Nature of

Things, so it is reasonable to concede that minor point. But we cannot know

anything else about them. They can neither touch nor be touched:

For by necessity the gods above

Enjoy eternity in highest peace,

Withdrawn and far removed from our affairs.

Free of all trouble, free of all care, the gods

Thrive in their own works and need nothing from us,

Not won with virtuous deeds nor touched by prayers.

Even the gods bow to the necessity of their limitation, their utter removal

from our world. Then we might as well spend our brief lives seeking a few modest

pleasures of the body, and the sweeter pleasures of the mind. These latter,

of course, will be severely restricted in scope, since we can know nothing

of the divine.

Our Liberations

We bide our time in the antechamber of death, persuading ourselves that we

do not care: “Death, then, is nothing to us, no concern,/ Once we grant

that the soul will also die.” How to wait while the slow stroke falls,

that is the object of the true philosopher. A benignant calm is all we can

ever know, all it will ever profit us to know.

So the terrible irony is that man, whose mind can search the stars, “raiding

the fields of the unmeasured All,” as Lucretius says in over-praise of

his master Epicurus, is the single being in creation whose faculties are quite

in vain. It is as if a malign fate had ordered it so.

But what if the One we wish to know knows us and wishes to be known by us?

That is no idle fancy but the startling claim that Judaism and Christianity

make: It is an assertion of a fact. Such a God either exists or he does not.

There is no third possibility. And if he does exist? Suddenly and with a

fearful abandon he may free us from our resigning and comfortable limitations.

He may knock loose the iron fetters forged by what we think we know and what

we think we cannot know. He may reveal even to great thinkers the mysteries

he has revealed to babes and innocents.

He may—rather, he will. And we will find the revelation a surprise,

but that is because we are sluggish in the ear and inattentive. But Truth himself

has promised it, and he means to be understood. •

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS

full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone

online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

30.4—July/Aug 2017

Soul Comforter

on Emily Dickinson & the Source of Our Hope by Josh Mayo

32.2—March/April 2019

The Problem of Pity

Misguided Mercy & Dante's Infernal Purgation by Joshua Hren

more from the online archives

29.5—Sept/Oct 2016

The True Atheist Myth

on Past & Present Atheism & the Invention of Happiness by Jordan Bissell

30.6—Nov/Dec 2017

The Messiah's Beauty

on Benedict XVI on the Fairest of the Sons of Men by Michael Martin De Sapio

20.8—October 2007

The Pearl of Great Wisdom

The Deep & Abiding Biblical Roots of Western Liberal Education by David Lyle Jeffrey

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor

Support Touchstone

00