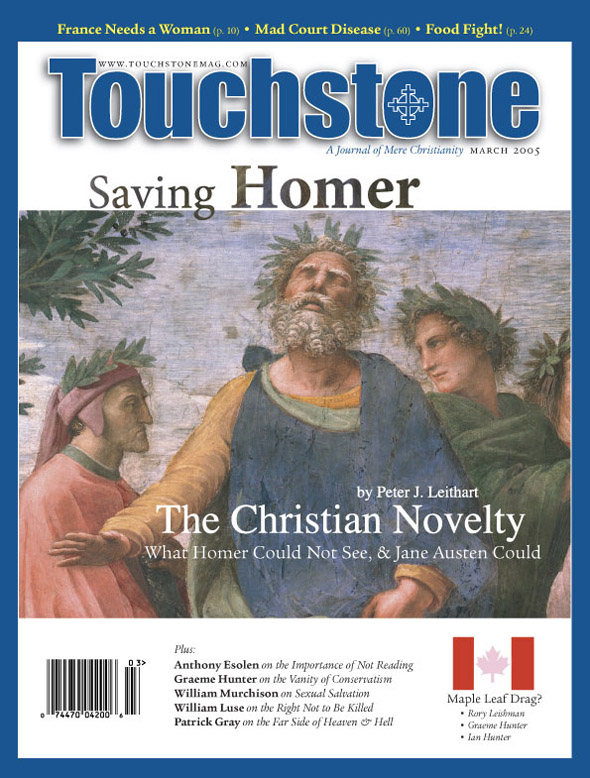

Feature

The Christian Novelty

What Homer Could Not See, & Jane Austen Could

Adam, Paul would have insisted, was as historical a person as you or I, and so was Jesus. Death entered a good world because Adam sinned, and new life entered the sinful world because Jesus obeyed and sent the Spirit. Adam’s sin was a historical event, and so was the resurrection of Jesus, and so was Pentecost.

These are the key points in human history, a history that includes Abraham, David, Solomon, Nebuchadnezzar, Cyrus the Persian, and Caesar Augustus, not to mention Augustine, Charlemagne, Napoleon, Saddam Hussein, Billy Graham, and Osama bin Laden. In Paul’s estimation, anyone who thought that the new life through Jesus pertained to some realm outside this history was simply an unbeliever. The gospel said otherwise.

Discerning this new life at work in the world is an act of faith, but if the gospel is true, if new life was unleashed in the world on Easter morning, it will leave footprints. And, as the church fathers were at pains to point out, it did. Athanasius noted all the pagans turning from their idols, all the warring tribes becoming brothers, all the swords being beaten into plowshares, and he used these things to expound the effects of the Incarnation.

One of the most evident illustrations of the effect of the gospel is found in the history of Western literature. That history is, to put it in Pauline terms, marked by a transition from the literature of death to the literature of life. Heroes of ancient epics are haunted by the fear of death, and recklessly pursue memorable deeds on the battlefield to secure some semblance of an afterlife. Eternal existence in the songs of poets is, after all, better than no after life at all.

The early Christian heroes, by contrast, were utterly fearless of death, not least the martyr’s death by torture. They went to their deaths gladly because they knew something the pagan world did not know: that the world was, despite appearances, a deeply comic place.

Tragedy to Comedy

A tragic story ends badly for the major characters. Hamlet is dead at the end of his play, and so are Macbeth, Lear, and Othello at the end of theirs. Comic stories end happily for the main characters. Fairy tales are comic: The boy rescues the girl, they marry, they live happily ever after. At the end of a tragedy, everyone is dead. At the end of a comedy, everyone is married.

Ancient literature is marked as the literature of death particularly in its bias toward tragedy. Greeks wrote comedies, of course, but their genius was for tragedy. William Butler Yeats was not your average orthodox Christian, but he recognized that a threshold had been crossed with the coming of Christianity. Classical culture, he wrote, was essentially a heroic culture, aristocratic and violent, its central myth the story of Oedipus, who kills his father and lives in incest with his mother. It was succeeded by Christian culture, which is democratic and altruistic, based on the myth of Christ, who appeases and reconciles his father, crowns his virginal mother, and rescues his bride the Church. . . . Tragedy is at the heart of Classical civilization, comedy at the heart of the Christian one.

Even when the ancients wrote comedies, moreover, their hearts did not seem to be in it.

W. H. Auden once commented that a Christian society could produce comedy of “much greater breadth and depth” than could a classical society. Its comedy was greater in breadth because classical comedy is based on a division of mankind into two classes, those who have arete [heroic virtue] and those who do not, and only the second class, the fools, shameless rascals, slaves, are fit subjects for comedy. But Christian comedy is based upon the belief that all men are sinners; no one, therefore, whatever his rank or talents, can claim immunity from the comic exposure and, indeed, the more virtuous, in the Greek sense, a man is, the more he realizes that he deserves to be exposed.

The Christian society’s comedy was greater in depth because, while classical comedy believes that rascals should get the drubbing they deserve, Christian comedy believes that we are forbidden to judge others and that it is our duty to forgive each other. In classical comedy the characters are exposed and punished: when the curtain falls, the audience is laughing and those on stage are in tears. In Christian comedy the characters are exposed and forgiven: when the curtain falls, the audience and the characters are laughing together.

Classical literature evokes no sense of “deep comedy,” no confidence that the world and history are fundamentally and profoundly good and under the government of an unthinkably good God, no belief that, in the words of Julian of Norwich (echoed by T. S. Eliot), “all will be well and all manner of thing will be well.” Deep comedy is a product of Christianity, a mark of resurrection life on the pages of Western literature.

In what follows, I explore two aspects of deep comedy: first, the central importance of the literature of laughter in the Christian Middle Ages; and second, the medieval concept of life as adventure. We will see that in both of these, the gospel has left its footprints.

Tragic Odyssey

Anyone who has read Homer’s Odyssey is likely to respond to Auden with a decisive, “Say what?” While the Iliad is the tragic epic of Greece, the Odyssey is the comic masterpiece. It tells the story of Odysseus’s homecoming to Ithaca, and his rescue of his wife Penelope from the unruly suitors who have taken over his house.

The epic has an almost evangelical feel to it: Odysseus, the disguised king, returns to his homeland, is despised and rejected of men, but eventually triumphs over his enemies and secures his bride. Though he faces danger in the Odyssey, death does not loom so near nor it is so fearfully depicted as in the Iliad. In fact, Odysseus conquers death: Though widely believed to be dead, he reappears; and at the center of the epic, he travels through the underworld and returns. This is a tragedy?

Yet even the Odyssey fails to arrive at a deeply comic vision of human life. Odysseus’s journey is not only a journey home, but also a journey back to the human world. Homer underlines this point with two contrasting epic similes. When Odysseus first arrives at Scheria, the island of the Phaeacians, he is described with an epic simile as “a mountain lion exultant in his power.” When he awakes at Ithaca, on his own island, however, he is no longer bestial:

As a man aches for his evening meal

when all day long

his brace of wine-dark oxen

have dragged the bolted plowshare

down a fallow field—how welcome

the setting sun to him,

the going home to supper,

yes, though his knees buckle,

struggling home at last.

So welcome now to Odysseus

the setting light of day.

Having become a predatory beast at Troy, Odysseus is slowly, deliberately, being formed into a man. Yet his return to humanity is simultaneously and necessarily an embrace of mortality. His is a journey to death and also, explicitly, a journey away from immortality. At the beginning of the epic, Odysseus refuses Calypso’s offer of immortality, choosing to remain human rather than share in the immortal life of the gods. At his final meal on Calypso’s island, he sits to the side, eating bread, while Calypso shares ambrosia (the food of the gods) with Hermes. His mortality has not put on immortality.

Odysseus’s story moves in the opposite direction from that of the gospel—not from death to life, but from the possibility of eternal life toward the certainty of death. The only way for Odysseus to escape death would be for him to renounce all that makes him a man: his kingdom, his bride, his son, his home. An immortal man is an impossibility; to be human means to be journeying toward death.

Death overshadows Odysseus at his homecoming. Even before he has had a chance to share a night of reunion with his wife, he tells her about Tiresias’s prophecy about his future, peaceful death. “One more labor lies in store,” he tells Penelope, before urging her toward the bed.

“An undercurrent of death” pervades the Odyssey, noted the classical scholar Charles Segal, “a deep and sad expression, characteristically Homeric, of the mixed and limited nature of all human happiness, of the inevitable involvement of man, even after his most strenuously attained and hoped for success, in time, change, and death.”

The Odyssey is the most comic of Greek epics. But it too is part of the literature of the reign of death.

A Comic Culture

Christian literature radiates a wholly different spirit from the classical. This is not how the story is usually told. The average textbook will tell you that medieval civilization was a dismal affair. Sober, serious, celibate churchmen ensured that everyone remained quite unhappy. Textbook writers find it easy to gather quotations from the church fathers condemning frivolity, and point out that Benedict discouraged laughter among monks.

In many ways this is a highly misleading picture. As the Russian literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin has shown, alongside the serious “official” or high culture, there was a comic and farcical folk culture, which frequently invaded high culture. At the “school festivals, which played a large role in the cultural and literary life of the Middle Ages,” for example, monastic novices and university students “ridiculed with a clear conscience during the festival everything that had been the subject of reverent study during the course of the year—everything from Sacred Writ to [their] school grammar.”

Comedy made its appearance at other festivals as well. “Medieval laughter is holiday laughter,” as Bakhtin wrote in The Dialogic Imagination. He mentions the risus paschalis (paschal laughter), when, in the days after Easter, people were allowed to laugh in church and preachers made jokes from the pulpit, the laughter celebrating their rebirth after the long season of fasting. The “Christmas laughter” ( risus natalis) “expressed itself not in stories but in songs. Serious church hymns were sung to the tunes of street ditties and were thus given a new twist.”

Comedy was not seen as a dispensable addition to serious reflection, but almost as an independent mode of thought. Laughter, wrote Bakhtin, was as universal as seriousness; it was directed at the whole world, at history, at all societies, at ideology. It was the world’s second truth extended to everything and from which nothing is taken away. It was, as it were, the festive aspect of the whole world in all its elements, the second revelation of the world in play and laughter.

Laughter’s Victory

This laughter reflected a larger medieval attitude toward death and evil. “It is the victory of laughter over fear that most impressed medieval man,” Bakhtin wrote.

It was not only a victory over mystic terror of God, but also a victory over the awe inspired by the forces of nature, and most of all over the oppression and guilt related to all that was consecrated and forbidden (“manna” and “taboo”). It was the defeat of divine and human power, of authoritarian commandments and prohibitions, of death and punishment after death, hell and all that is more terrifying than earth itself.

Medieval man expressed this victory by presenting death in “a droll and monstrous form, the symbols of power and violence turned inside out, the comic images of death and bodies rent asunder. All that was terrifying becomes grotesque.”

The high literature of the period is also marked by these comic elements. Medieval writers loved to parody serious scholarly pursuits (they even parodied grammars). Even works that were not parodies have elements of laughter and comedy. Peter Hawkins has recently pointed out that the Divine Comedy is a comedy not only in the literary sense (it has a happy ending) but also in the common sense of the term. Many passages are supposed to be funny. Even plays on sacred themes, like the nativity drama known as the Second Shepherds Play, included comic scenes and characters. Chaucer’s penchant for bawdy humor was not unique to him.

Another learned writer of the same period, Master Nivardus of Ghent, produced a Latin beast epic, Ysengrimus, which lies somewhere near the Roadrunner and Coyote cartoons and Br’er Rabbit. Ysengrim is a wolf, consistently tricked by the wily fox Renard. Renard convinces Ysengrim to fish in a frozen stream with his tail, and when his tail freezes into the stream, Renard sends some peasants out to beat him.

A wild boar convinces Ysengrim to enter a monastery, promising regular and sumptuous meals. Tonsured though he be, the wolf is unable to learn anything and is quickly dismissed from the monastery. Renard, meanwhile, has seduced Ysengrim’s wife. Finally, Ysengrim is killed by a herd of pigs, and Renard speaks a mock funeral oration over the body.

A New Attitude

Deep comedy involves not only laughter, but a particular attitude toward the world, expressed in the medieval concept of life as an adventure.

For ancient man, the world was sharply divided between the ordered cosmos of the city and the chaos of the world outside the four walls. Socrates would rather drink his hemlock than suffer exile from Athens. Odysseus is the great adventurer of Greek legend, but his sole intention is to get home as quickly as possible, for beyond Ithaca, the world is populated by cyclopses, witches, and monsters of the deep. The ancient man knew that every time he ventured outside the walls, he was entering alien territory, a world inhospitable to human life.

During the high Middle Ages, literature begins to reflect a new attitude toward the world. During the last quarter of the twelfth century, French writers began to write in a new genre, which has come to be known as “romance.” These romances often included love stories, but they also included tales of adventures, narrow escapes, knights errant rescuing distressed damsels, all the excitement we associate with medieval stories. This was something new. Before this, Christian heroes fought to defend Christendom against Islam. Twelfth-century literary heroes sought adventure for the sake of adventure.

Antiquity had had its romances, Bakhtin pointed out. Some were romances of endurance, in which the character’s goal was merely to stay constant through a series of adventures, and others were romances of transformation, in which the character was changed by his circumstances and the events of the story. Odysseus illustrates the first, the protagonist of Apuleius’s The Golden Ass the latter.

Both sorts of romance, and both sorts of adventurers, however, share a key characteristic: According to the German Marxist historian Michael Nerlich, none of the characters want to be adventurers. In these stories, as Bakhtin emphasized, “an individual can be nothing other than completely passive, completely unchanging” and is “merely the physical subject” of events.

After the twelfth century, things changed, suddenly and permanently. In the Arthurian romances of Chretien de Troyes and his legions of imitators, Nerlich wrote, the adventurer seeks the adventure, and in doing so, both he and his quest are glorified. Even the meaning of the term “adventure” changes: Having meant “fate” or “chance,” it now means something actively sought and then endured, although what happens cannot be predicted.

This willingness to seek out adventure in the world outside one’s home reflects a changed attitude toward the world. Leaving the confines of one’s home and city loses all its terror, though it is still dangerous. To put it another way, the ancient distinction between the “normal” world of the home and city and the “magical” and “mysterious” world outside dissolves. Instead, the entire world has become normalized, every place seen as a place subject to God and filled with his presence.

At the same time, all places become infused with magic. As Bakhtin said, “The whole world becomes miraculous, so the miraculous becomes ordinary without ceasing at the same time to be miraculous . . . the entire world is subject to ‘suddenly.’”

Courtly heroes set out on adventures as much for the sake of their souls as for any good they might accomplish. Adventuring is essential to the development of character, or, in theological terms, to sanctification. Knights embark on adventures to fulfill certain ethical demands and to demonstrate their chivalric virtues to their lady, their liege, or their Lord.

Paul’s Adventures

Of course, many factors were at work in the development of the comedy and adventuring of medieval Christian literature, but it seems undeniable that Christianity itself was one of the key factors, for adventure-seeking did not begin with Chretien.

Arguably, it begins with Paul and Acts, and comes to remarkable fruition in the lives of many of the early monks and missionaries of Christian history. Irish monks in particular, with their practice of White Martyrdom, are the precursors of the venturing knights of the high Middle Ages. Even Beowulf, though still operating in a much more epic environment, goes to Hrothgar seeking to help. He is not a passive adventurer, at the mercy of fates. He goes out looking for dangers to conquer.

This outward movement is deeply rooted in biblical history. Abraham is simply a different kind of creature than had ever existed in literature before. For the Greeks, the polis was the world, the ordered kosmos, and to step outside it was to move into chaos. Abraham’s story begins with a call to leave his father’s house and venture toward a land he has never seen by a route that has not been shown. Abraham is a different kind of human being from Socrates or Odysseus, and he engenders a different sort of people.

The “adventuring” mentality was given an even stronger impetus by the Christian gospel. The Old Testament order in Israel was similar in many respects to the order of ancient Near-Eastern civilizations or Greece. In Israel, as in Athens, the city and temple were seen as the center of the world. Everything moved centripetally toward the temple. Exile was the final and most severe curse of the Old Covenant.

At the heart of the gospel, however, is the announcement that this order of sacred center and profane distance has been destroyed. Instead of a single place for an earthly temple, the New Testament announces a heavenly temple, equally accessible from any point on earth. The commission of the Greater Joshua is not to enter the land in order to stay there. The commission is to “go, make disciples of all nations.”

The gospel further promotes the deep comedy of adventure because it declares that there is no chaos outside the city. Christ is Lord of all, and all things are, in principle, subdued to him. Irish monks can be confident that wherever the sea might take them, they will still be in God’s world and will meet human beings who need a Savior.

Tragic & Comic Gods

Ultimately, like most things, the difference between the ancient tragic and the Christian comic mentality, the difference between romances of endurance and romances of adventure, comes down to questions of theology proper, the doctrine of God.

On the surface, ancient religions were profligately polytheistic. Polytheism is not a faith calculated to offer confidence. Propitiating Aphrodite might well put you on a collision course with Hera, and honoring Apollo might offend Dionysus. Adventures are dangerous because the adventurer, like Aeneas, always runs the risk of stumbling onto the turf of a hostile deity.

Behind the surface, ancient religions were often unitarian. Impersonal fate was the real power governing the world, and, in some ancient myths, fate controls even the gods. Philosophers of the ancient world were even more overtly unitarian.

Unitarianism is inherently tragic because it is inherently gnostic. Any emanation from a unitarian god is a diminution. For unitarianism, the act of creation is inherently tragic, and so is every stage of history. Hence, the myths of origins from the ancient world often trace a devolution from a golden age through a silver age toward a merely human age, an age without glory.

For Christianity, however, the confession of the Trinity meant that there was emanation inherent in God, an emanating Son who was of one substance with the Father. The Son was eternally begotten from the Origin of the Father, but without any diminution. A Trinitarian God can thus make a world that is different from himself but not distant. For the Trinity, creation is not tragic because eternal begetting is not tragic. On the contrary, just as the Son who comes from the Father is the glory of the Father, so the creation is a crown of glory to the Son. The very act of creation, and all the history that flows from it, is inherently comic.

More directly, Christians worship a God whose crowning work is nothing less than a grand aventure, a voluntary movement from the security of the Triune fellowship into the alien and dangerous world of sinful human beings. Christians proclaimed an “advent” of God the Son, and it is no accident that there is an etymological connection between “advent” and “adventure.” It is no accident that the people of an adventurous God should produce a literature no one had ever seen before, a literature of deep comedy, a literature of hope and joy and laughter. •

The Deeper Comedies

• Dante, The Divine Comedy (Dante simply called it “The Comedy,” though he probably meant “ the comedy,” the only one, the one that gives meaning to all the other comedies.)

• Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (and for a very pleasant read, check out the Jonah story in Patience, by the same poet)

• Ariosto, Orlando Furioso (Crazy Roland, of course because he has fallen in love)

• Shakespeare, As You Like It, Measure for Measure, and The Winter’s Tale

• Cervantes, Don Quixote (especially the episodes in Book Two, wherein Sancho is transformed into King Solomon)

• Henry Fielding, Joseph Andrews (best portrayal of a godly minister this side of Bing Crosby)

• Manzoni, The Betrothed (a beautiful comic novel about loyalty and trust in Providence)

• Jane Austen, Emma (a more slyly humorous and “deeper” psychological comedy than the better-known Pride and Prejudice)

• Charles Dickens, Bleak House (the third-greatest novel ever written)

• Goncharov, Oblomov (a dark horse, but sunnier and less tending to nihilism than the works of his contemporary Gogol)

• Italo Calvino, Cosmicomics (the author is not even Christian, but he’s been infected with the Christian comedy bug more than he wants to admit)— Anthony Esolen

More Deeper Comedies

Anne Barbeau Gardiner:

• Dante, The Divine Comedy

• Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

• Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales

• Cervantes, Don Quixote

• Shakespeare, The Tempest

• Milton, Paradise Lost

• Nearly all of Molière

• Goncharov, Oblomov

• Tolstoy, Death of Ivan Ilych, and his short religious tales from the turn of the twentieth century

• Jean Giraudoux, The Madwoman of Chaillot

• Karel Capek, The Life of the Insects

• Flannery O’Connor, Everything That Rises Must ConvergeGraeme Hunter:

• Shakespeare, The Tempest, The Winter’s Tale, and Pericles

• Christopher Marlowe, Doctor Faustus

• John Bunyan, Pilgrim’s Progress

• George Bernanos, Dialogues of the Carmelites

• Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory

• C. S. Lewis, Chronicles of Narnia

• Michael O’Brien, Father ElijahPeter J. Leithart:

• Dante, The Divine Comedy

• Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

• Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales

• Shakespeare, Twelfth Night (or virtually any of his comedies, and some tragedies, Macbeth for instance)

• Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice and Emma

• Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov

• John Buchan, Sick Heart River

• Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory

• T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets

• C. S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces

• Ron Hansen, Atticus

Peter J. Leithart is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church in America and the president of Trinity House Institute for Biblical, Liturgical & Cultural Studies in Birmingham, Alabama. His many books include Defending Constantine (InterVarsity), Between Babel and Beast (Cascade), and, most recently, Gratitude: An Intellectual History (Baylor University Press). His weblog can be found at www.leithart.com. He is a contributing editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor