Loving the Law

Anthony Esolen on the Liberated Life of Sonship & Obedience

If I were to choose which verses from Scripture were most flatly incomprehensible to the man of our passing age, they would come from the longest of the psalms (119), that paean of joy and delight in the law of God. You might choose any of the poem’s sections, each of which contains eight verses beginning with one of the letters of the Hebrew alphabet, in order from the first to the last. Every verse in the poem plays upon one of the words for what God has spoken and set down as a rule for life: word, law, precepts, commandments, statutes, decrees, judgments, testimonies, ordinances, faithfulness, and so forth. If I had to choose one section, it would be this, under the letter mem (97–104):

O how I love thy law! It is my meditation all the day.

Thou through thy commandments hast made me wiser than mine enemies: for they are ever with me.

I have more understanding than all my teachers: for thy testimonies are my meditation.

I understand more than the ancients because I keep thy precepts.

I have refrained my feet from every evil way, that I might keep thy word.

I have not departed from thy judgments: for thou hast taught me.

How sweet are thy words unto my taste! Yea, sweeter than honey to my mouth!

Through thy precepts I get understanding: therefore I hate every false way.

Both Enthralled & Stunned

We with our libertarian instincts are apt to consider the law as at best a useful curb against violations of our person and our liberty, quite unnecessary if people would but cease being violent, avaricious, and obnoxious. Otherwise, we do not need it. Misunderstandings of the gospel can encourage this attitude of disparagement, even of outright rejection—and here we need not be thinking of the Mosaic law but of the moral law as taught by the churches in their catechisms, or as discernible by reason and affirmed and clarified by divine revelation. It is hard to read the New Testament and come up with such a freedom to be lawless, but the imagination of man is ever at work, for good and for evil.

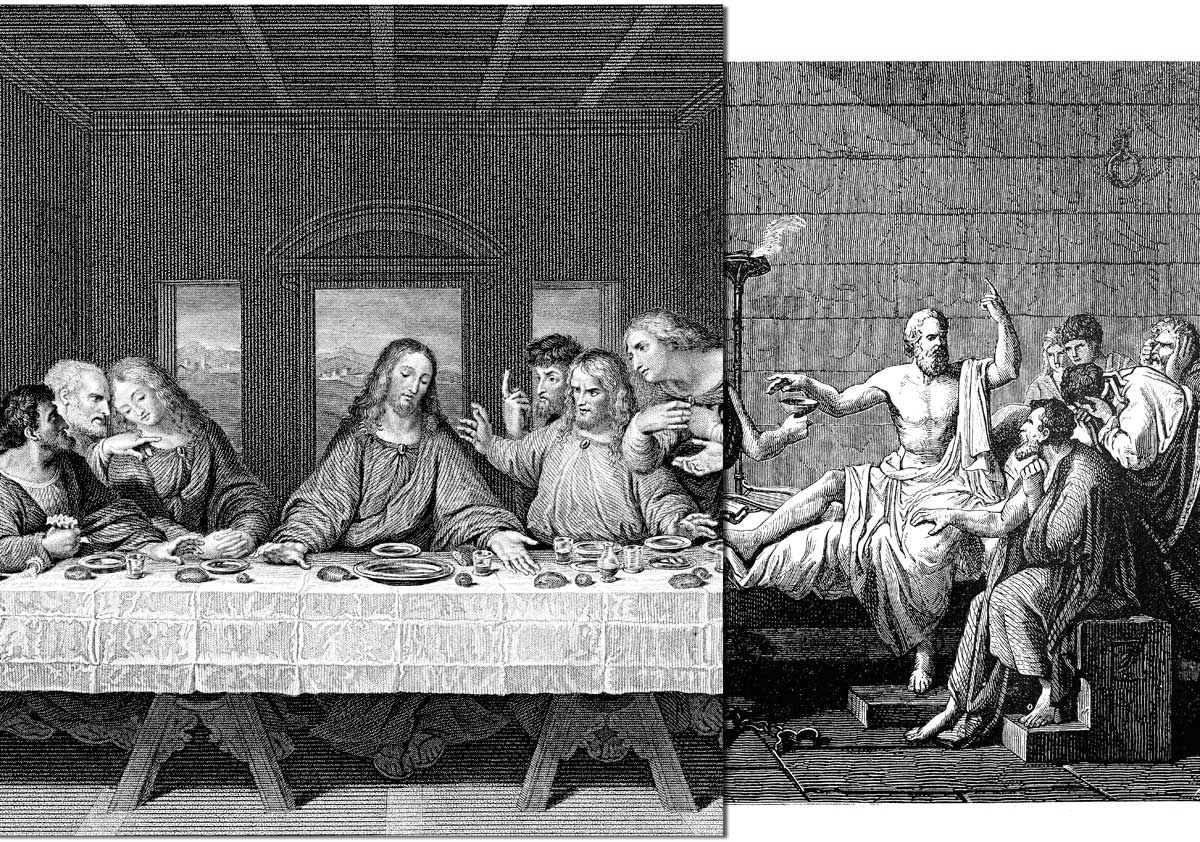

Jesus is careful to specify that he has not come to abolish the law but to fulfill it (Matt. 5:17), and if we take his own examples to heart, whereby on his own authority he raises the law to its proper height and purifies it of the dross of human self-theatrics (such parading is the true meaning of hypocrisy), we see that we are to love the law even more than before, as it calls us on to greater virtue and deeper commitment to the will of God.

Here is a typical example: “Ye have heard that it was said by them of old time: thou shalt not commit adultery. But I say unto you, that whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart” (Matt. 5:27–28).

They who heard Jesus speak in this way must have been at once enthralled and stunned, because once he makes the revelation, it is clear to any open mind and heart that it must be so; yet we also fear that the standard is set at an impossible height. So did the disciples themselves show their dismay when Jesus similarly forbade divorce: “If the case of the man be so with his wife, it is not good to marry” (Matt. 19:10).

And we, too, are made rightly uncomfortable to hear that “it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God” (Mark 10:25). The disciples were “astonished out of measure, saying among themselves, Who then can be saved?” (26). Now, this warning against putting our trust in riches is by no means foreign to the law. It is a way to understand, from the earthly side, what it means at a minimum to keep the Sabbath; for the command to feast is a command to do something radically different from garnering up riches for the sake of garnering them.

We may thus see that the promise of prosperity for the children of Israel is not of the mercantile kind for which the men of Canaan and Tyre committed human sacrifice. The Israelites were not to use the advantage of wealth to wring interest from their neighbors (Lev. 25:35–37); they were not to hoard the manna or to try to gather it on the Sabbath (Ex. 16:19,25); they were not to muzzle up the ox treading out the corn (Deut. 25:4), or to go back to the fields to snatch up every last ear of corn the gleaners had missed or dropped (Lev. 23:22). But they were to devote much of their wealth to the worship of the Lord—to the feast: hence the elaborate instructions regarding the Ark of the Covenant, the tabernacle, the mercy seat, the altar, and “holy garments for Aaron thy brother, for glory and for beauty” (Ex. 28:2).

Liberating Bonds

But in both subjects I have broached here, what Jesus does to raise the law is liberating, not onerous, so that he can truly say, “My yoke is easy, and my burden is light” (Matt. 11:30). To tithe mint and cumin is to pick about the common weeds. But to take a lesson from the lilies of the field is to relieve yourself of the burden of pretending that you can arrange your own future. How many naturally virtuous men provide for their families so well that they lose the joy of the family in doing it, and sometimes they lose the family itself?

Similarly, to hear that “what therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder” (Mark 10:9) is to learn of a bond that liberates, a bond that you cannot enter into with a right mind unless you have a freedom of heart, the freedom of a total and irrevocable gift, of casting your bread upon the waters (Eccl. 11:1), of saying, with Ruth, as she leaves behind all that she knew, “Thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God” (Ruth 1:16). It means not having to worry about whether your husband or your wife will still be yours, come this time next year; the freedom is unconditional.

So if we abide in his word, says Jesus—using one of the terms the Psalmist uses, and with a similar force, though it is his word, which the Father has given to him and which he gives in turn—“ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free” (John 8:32). Riches do not liberate, nor does sexual pleasure, nor does power, for “it is better to trust in the Lord than to put confidence in princes” (Ps. 118:9). The truth does liberate, and Jesus brings us the truth in its fullness, because he is himself “the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6).

A Gift & a Delight

Now let us return to the Psalmist and his meditations. The law of God is a great gift. It is more than a social machine that happens to do good work; and good work it indeed does, as it is impossible to imagine, without the law, that the Jews could have survived as a people through one diaspora after another, always outnumbered and usually persecuted, hemmed in, despised. It brings them life. “What nation is there so great,” says Moses to the people, “that hath statutes and judgments so righteous as all this law, which I set before you this day?” (Deut. 4:8).

The Psalmist does not regard them as bonds, or as a set of daily scruples. To meditate upon them, here, is to regard them with love, as something you never come to an end of admiring, as if they were an open vista, with new wisdom and glory to be found every day. The commandments of God have made him wiser than his enemies, he says, “for they are ever with me,” in Hebrew ki le ‘olam hi li, echoing the most divine characteristic of God’s mercy, that it endures forever, le ‘olam (Ps. 118:1). Thus does the loving receiver of the law enter into the presence of God, who is not bound by time and its chances and changes, and so he can well say, “I understand more than the ancients.” The word zaqen, here translated as “ancient,” also means “elder,” in which case the Psalmist, though he is young, is wiser than those who are set above him in civil authority, because he drinks from the living well. The law gives him keen eyes and an understanding heart such as Solomon asked for, to govern his people (1 Kings 3:9).

The law, then, does more than apply to the boundary stones of human affairs: it is more than the legal and the civic. It gives you eyes to see, as Solomon saw when he discerned the difference between a woman devoured with envy and the true mother of the disputed child, whose “bowels yearned for her son.” And “all Israel heard of the judgment which the king had judged; and they feared the king: for they saw that the wisdom of God was in him, to do judgment” (3:26,28). The reaction of the people is filled with a kind of holy fear, as when you draw near to the sublime.

Can we imagine what it might have been like to look upon the eyes of Jesus, in the cool of the evening, when he was praying or thinking quietly? Something of that mysterium tremendum has thrilled the heart of the Psalmist. And why not? The last thing a true encounter with the law could be is prosaic. “How sweet are thy words unto my taste!” he cries, “yea, sweeter than honey to my mouth!” Honey was the sweetest thing the Psalmist knew; honey that brought light to the eyes of Jonathan, weary almost to fainting (1 Sam. 14:27); honey that seemed to flavor the manna from heaven (Ex. 16:31); and the richness of Canaan made it a land “flowing with milk and honey” (Ex. 3:8, and passim).

We, then, are to love the law because it is lovable, it is sweet; and just as it makes the Psalmist wiser than the elders or the men of old, so, using the same grammatical construction, he says that the law is sweeter than honey. Recall the words of that holy singer of love: “Thy lips, O my spouse, drop as the honeycomb; honey and milk are under thy tongue” (Songs 4:11). With such a passionate embrace of the soul does the Psalmist delight in the law of God.

A Light & a Power

Why, then, do many Christians seem shy not only of the Mosaic law in particular but of any established moral precepts whatever? I might say that Marcionites and antinomians we will always have with us; Adamites walking nude in public; and other Adamites, less courageous, accepting the same sort of thing in their tacit assumptions regarding Christian life, as if their salvation were to be liberated from the moral law and not into a fuller life of obedience, that is, of sonship.

Here, the last verse of the passage I have chosen can instruct us: “Through thy precepts I get understanding: therefore I hate every false way.” The Hebrew adjective for “false,” shaqer, is the same one we find in the commandment, “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor” (Ex. 20:16). It means more than that what you say is not the case. It suggests active deceit and malice: “But ye are forgers of lies,” says Job to his accusers (Job 13:4). It also suggests vanity, futility: as if you might reach for a handhold on the side of a cliff and have it prove to be but a crumble of shale. So “a horse is a vain thing for safety: neither shall he deliver any by his great strength” (Ps. 33:17).

We invert the passion of the Psalmist, then, in bridling against the law, and we do it because our ways are false, as Jesus says with all the force of simplicity: “Men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil” (John 3:20). The law that was to govern Israel in all her ways of worship and of life, was for the Psalmist the very word of God, “a lamp unto my feet, and a light unto my path” (119:105). But for those who choose the lie, it is a light to catch them with, to show their deeds; or to shine through their emptiness and show them for the shadows they have made of themselves.

I do not suggest here that Christians are to be bound by the specifics of ancient Jewish ritual, which Christ has fulfilled and transformed and exalted, or that we are bound to observe the legal punishments for crimes; Jesus himself extended clemency to the woman caught in adultery, commanding her to go and sin no more. But just as the Christian life is to be more merciful, so it must be purer in its aspirations and more lovingly dedicated to moral truth. Just as it is to be the life of sons and not slaves, so must it be all the readier and more cheerful in obedience, as Jesus was, who says of himself that the Son does only what he sees the Father doing (John 5:19). Then will the moral law be in us a power, a dynamism of mind and heart, a gift to ourselves and to our countrymen, a fountain of living water springing up to eternal life.

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on the ten commanments from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor