The Narrow Gate

Who Says the Broad Way to Destruction Is Forever Closed?

There are few doctrines that less recommend Christianity to the men and women of our time than the proposition that unrepentant sinners will be condemned to an eternity of misery in hell. Doubtless, anyone who has attempted to present the case for Christianity, or even to defend his own belief, in ordinary conversation with an acquaintance has been met with a rejoinder along the lines of “I can’t believe in a God who sends people to hell just for having sex before marriage” or “for not being baptized” or “for not going to church on Sunday”—the list of sins regarded as trivial may be long and varied depending upon the disposition of the interlocutor. The average person who complains in this fashion may even retain a comfortable, though vague, notion of God, but he will probably pay little attention to such a God in which he professes so tepid a belief.

To be sure, there are more sophisticated rejections of the doctrine of eternal punishment in hell of unrepentant sinners, and it is by no means a recent development. Although the doctrine of damnation has been the consistent teaching of the Church, supported by the vast majority of Christian teachers, there have been dissenters at least as early as Origen (AD 185?–254?). In the following century, Gregory of Nyssa (ca. 335–ca. 395) also seems to have maintained that eventually all men, and perhaps all rational creatures, would be saved. Both Origen and Gregory of Nyssa seem to regard hell as similar, if not identical, to purgatory in Catholic teaching. There are a number of other ancient writers, mostly in the Eastern tradition, who teach some form of universal salvation, but the doctrine diminishes and virtually disappears (especially in the West) in the Middle Ages and Early Modern period until it re-emerges among (mostly Protestant) Christians in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, gaining strength down to our own times.

By the latter half of the twentieth century, even Catholics of a generally traditional and orthodox disposition were beginning to qualify to some extent the doctrine of eternal punishment in hell, although it remains the teaching of the Catechism of the Catholic Church (1033–1041). Perhaps the most prominent Catholic theologian of this persuasion is Hans Urs von Balthasar, who suggests that, although hell exists, we have no evidence that any soul is actually there. In his very popular and influential book, Catholicism: A Journey to the Heart of Faith (2011), Bishop Robert Barron endorses von Balthasar’s proposition. Although “we must accept the possibility of hell,” he says,

we are not committed doctrinally to saying that anyone is actually “in” such a place. We can’t see fully to the depths of anyone’s heart; only God can. Accordingly, we can’t declare with utter certitude that anyone—even Judas, even Hitler—has chosen definitively to lock the door against the divine love. (257–258)

Hell is thus a logically necessary counterpart to heaven, but eternal damnation is not a necessary corollary to hell.

An Exorbitant Claim

The tentative suggestion that hell is real but empty, a bold step for a Catholic theologian, is not merely unsatisfactory to David Bentley Hart; it is unworthy of serious consideration. His book, That All Shall Be Saved (2019), makes what, he admits, “is an exorbitant and somewhat insolent claim”:

I have very small patience for this kind of “hopeful universalism,” as it is often called. As far as I am concerned, anyone who hopes for the universal reconciliation of creatures with God must already believe that this would be the best possible ending to the Christian story; and such a person has then no excuse for imagining that God could bring any but the best possible ending to pass without there being in some sense a failed creator. The position I want to attempt to argue, therefore, to see how well it holds together, is far more extreme; to wit, that, if Christianity is in any way true, Christians dare not doubt [emphasis in original] the salvation of all, and that any understanding of what God accomplished in Christ that does not include a final apokatastasis in which all things created are redeemed and joined to God is ultimately entirely incoherent and unworthy of rational faith. (65–66)

The belligerence of this assertion evinces a remarkable certitude about God’s intention in creating mankind and the universe and, to borrow a phrase from C. S. Lewis, puts “God in the dock.” Any God who would condemn anyone to an eternity of misery for any reason is an immoral monster and therefore not worthy of worship, therefore not God at all. Such is the gravamen of the argument, which irresistibly recalls Milton’s Satan, persuading Eve not to fear the threat of death for eating the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil: “Will God,” the Serpent asks, “incense his ire / For such a petty Trespass . . . ? / God therefore cannot hurt ye and be just; / Not just, not God; nor feard then nor obeid: / Your feare it self of Death removes the feare” (Paradise Lost IX.691–693, 700–702).

As the most eminent, as well as the most vehement, proponent of the doctrine of universal salvation, David Bentley Hart’s disquisition offers a convenient occasion for reconsidering Christian teaching regarding hell and damnation. Demonstrating that there is, in fact, a hell of eternal punishment, which does include at least some denizens is, however, less important than dealing with the consequences for the interpretation of sacred Scripture, of our understanding of the earliest fathers of the Church, and of our relationship with God, which the attempt to undermine the belief in eternal punishment entails. Hart’s treatment of Scripture and patristic sources is, frankly, rather careless and cursory; it is his understanding of the moral relation between men and women and our Creator and Savior that really drives his argument.

The Meaning of Matthew 25

Before taking up the moral argument, however, his remarks regarding the status of the teaching in Scripture and in the ancient doctrinal tradition must be considered. He claims that there are a very few passages in the Gospels that may be construed as teaching the reality of eternal damnation in hell and a few more in the book of Revelation. “The whole idea,” he asserts, “is . . . entirely absent from the Pauline corpus, as even the thinnest shadow of a hint. Nor is it anywhere patent in any of the other epistolary texts” (92). These asseverations do not, however, bear up under scrutiny.

Hart identifies Matthew 25:46 as “the strongest evidence” for the concept of a perpetual damnation, but only as “traditionally understood” (92); it is difficult, however, to see an alternative to the traditional understanding. Beginning at verse 31 of chapter 25, our Lord describes the coming of the Son of Man in his majesty, when he will separate humanity into two groups “as the shepherd separateth the sheep from the goats.” He will invite the “sheep” on his right hand to “possess you the kingdom prepared from the foundation of the world” (25:34), but the “goats” on his left hand, who have failed to succor “one of these least,” are ordered into “everlasting fire which was prepared for the devil and his angels” (25:41). The Lord, after explaining their derelictions to the “cursed,” concludes the chapter with a sharp dichotomy between the sheep and the goats: “And these shall go into everlasting punishment: but the just, into life everlasting” (25:46).

Now, it is correct to point out that the Greek word aiōnios, here translated “everlasting,” comes from the noun aion, meaning the length of a human life, a generation, a great length of time; but it means eternity as well, not only in the New Testament but also, for instance, in Plato’s Timaeus. Moreover, if to pur to aionion (v. 41) does not mean “eternal fire” and kolasin aionion (v. 46) does not mean “eternal punishment,” then it is difficult to see how zoen aionion (v. 46) can mean “eternal life.” If damnation is provisional, then it would seem that salvation must be as well.

In Matthew’s account, our Lord uses a simile in comparing the separation of the accursed and the just to a shepherd separating the sheep from the goats, and one may take the “everlasting fire” as a metaphor for the punishment of hell (although some Christians insist upon the presence of actual fire in hell), with both images creating a vivid pictorial quality in the scene. There is nothing “vague” about it; it has a plain literal sense. Metaphors and similes by themselves do not constitute allegory or a spiritual sense that requires decoding, and, in any case, allegory does not exist apart from the literal or historical meaning.

As St. Thomas Aquinas points out, while the spiritual sense is distinct from the literal or historical sense, it is not wholly unrelated to the historical sense, much less in contradiction to it. “The spiritual sense is founded upon the literal sense and assumes it” (Summa Theologiae I.i.10). Further, St. Thomas also observes, citing the De Doctrina Christiana of St. Augustine, that “nothing is delivered obscurely in one place in sacred Scripture that is not expounded clearly in another” (Quaestiones Quodlibetales VII.vi.14). Finally, St. Thomas, again following St. Augustine, points out that Scripture must be read “analogically” so that the truth of one passage does not contradict another (Summa Theologiae I.i.10 ad 2). Therefore, other passages in the Bible must be read so as not to conflict with what seems to be the perfectly clear literal meaning of Matthew 25:46.

Hart denies this principle by conflating it with biblical fundamentalism:

I am not very tolerant of what is sometimes called “biblicism”—that is, the “oracular” understanding of scriptural inspiration, which sees the Bible as the record of words directly uttered by the lips of God through an otherwise dispensable human intermediary, which entails the belief that the testimony of the Bible on doctrinal and theological matters must be wholly internally consistent—and I certainly have no patience whatsoever for twentieth-century biblical fundamentalism and its manifest imbecilities. (85–86)

I have added the italics to show how Hart has slyly put the principle of analogical interpretation in a relative clause modifying another relative clause and associated it with a perspective that few of his more formidable antagonists would accept. If there is no consistency in the teaching of the Bible, however, a heretic has the license to jettison whatever fails to comport with his version of Christianity. Marcion, for instance, used the principle to deny the validity of the entire Old Testament.

Numerous Affirming Texts

Contrary to Hart’s claim, there are numerous texts throughout the New Testament that may plausibly be read as affirming the existence of the eternal punishment of sinners in hell. For example, Matthew (3:11) quotes John the Baptist as saying, just before he baptizes our Lord with water, that the Messiah “shall baptize you in the Holy Ghost and fire.” In the next verse he depicts the Messiah with his “fan in his hand, and he will thoroughly cleanse his floor and gather his wheat into his barn; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire” (3:12). To be sure, the figure of the Messiah as a thresher is “metaphorical,” but a metaphor, any figure of speech, signifies something. Unless our Lord is giving lessons in agronomy, the thresher is a figure for the Lord and Judge, and the wheat and the chaff signify, respectively, the saved and the damned. The “unquenchable fire” (puri asbesto) is distinct from the fire associated with the Holy Ghost and anticipates the “everlasting fire” (pur aionion) of chapter 25.

As St. Thomas points out, “lion” in a given similitude may signify either Christ or the devil; hence, “the meaning of metaphorical terms is not fixed” (Quaestiones Quodlibetales VII.vi.14). Likewise, “fire” can indicate opposite figurative meanings, depending on the context. Very often it plainly indicates the torment due to sin, and in at least three more passages in the Gospels, in addition to the verses in Matthew 3 and 25, which we have examined above, the fire is specified as “everlasting” or “unquenchable” (Matt. 18:8; Mark 9:43,48; Luke 3:17). The Epistle of Jude (1:7) says that Sodom and Gomorrah, and the neighboring cities, in like manner, having given themselves to “fornication and going after other flesh, were made an example, suffering the punishment of eternal fire.” Since the historical burning of the physical cities obviously does not go on forever, it seems reasonable to infer that Jude is indicating the eternal fate of their sinful inhabitants.

But the phrase “eternal fire” comprises only a few of the numerous references in the New Testament implying the possibility that unrepentant sinners will suffer everlasting punishment. We may begin by noticing several references that suggest very strongly that some sins will never be forgiven, and Judas is specifically cited as an individual who cannot hope for redemption.

For example, in Matthew our Lord says that, although speaking against the Son of Man will be forgiven, “he that shall speak against the Holy Ghost, it shall not be forgiven him, neither in this world, nor in the world to come” (Matt. 12:32). Neither in this world, nor in the world to come. In Mark, similarly, he says, “But he that shall blaspheme against the Holy Ghost shall never have forgiveness, but shall be guilty of an everlasting sin” (Mark 3:29). However this sin against the Holy Ghost may be defined, the statement that it is unforgivable seems altogether clear and straightforward.

Speaking of his betrayer, namely, Judas, our Lord says, “it were better for him, if that man had not been born” (Matt. 26:24). In Mark (14:21) and Luke (22:22) he says essentially the same thing. In John, Jesus says, of Judas, that he has kept all those whom his Father gave him, “and none of them is lost, but the son of perdition, that the scripture may be fulfilled” (John 17:12). If it were better for a man never to have been born, surely he is precluded from entering heaven; and there is nothing allegorical, figurative, or in any way obscure in these passages.

There are, in addition, a number of passages in the Gospels that seem to draw a sharp contrast between the Elect (or the Chosen) and the rest, suggesting that, although all are offered the grace that leads to salvation, not all take advantage of it. According to St. Matthew, our Lord says, “Enter ye in at the narrow gate: for wide is the gate, and broad is the way that leadeth to destruction, and many there are that go in thereat. How narrow is the gate, and strait is the way that leadeth to life, and few there are that find it!” (Matt. 7:13–14). Similarly, he says, “So shall the last be first, and the first last. For many are called, but few chosen” (Matt. 20:16).

If these ominous observations are not intended as a warning that salvation is not guaranteed to everyone, it is difficult to see what their purport could be. At no point are they qualified with the suggestion that, sooner or later, everyone will find the narrow gate, that all those called will be chosen. In Luke’s Gospel, our Lord is asked directly, “are they few that are saved?” His answer is hardly reassuring: “Strive to enter by the narrow gate; for many, I say to you, shall seek to enter, and shall not be able” (Luke 13:23–24).

A Persistent Tension

There are, of course, other verses that seem to invite a universalist interpretation. In his account of the preaching of John the Baptist preparing the way for the Messiah (Luke 3:3–6), the Evangelist quotes the words of Isaiah (40:5): “All flesh shall see salvation”; and when the Samaritans refuse to receive him, and James and John suggest that they ought to call down fire from heaven to consume them, Jesus rebukes the disciples, saying, “The Son of Man came not to destroy souls, but to save” (Luke 9:56). These verses suggest universalist overtones but are hardly dispositive: that the Incarnate Son of God came to save, not to destroy, souls during his earthly life does not negate his Second Coming in glory as Judge.

Hart dismisses the idea that there is a persistent tension between Christ’s will to save all men and his nonetheless allowing them to persist stubbornly in willful sin to the point of final damnation. Still, it is a recurrent motif in the synoptic Gospels and is, perhaps, most starkly manifest in the Gospel according to John. “If any man hear my words,” Jesus says, “and keep them not, I do not judge him: for I came not to judge the world but to save the world” (John 12:47). In the very next verse, however, this irenic remark is qualified: “He that despiseth me, and receiveth not my words, hath one that judgeth him; the word that I have spoken; the same shall judge him on the last day” (John 12:48). If the intention of the latter verse is not to put a limit on the universal offer of salvation, then it is difficult to see what its purpose could be, or why, at some point in one of the four Gospels, our Lord does not say, at least to his inner circle, “Don’t worry: eventually everyone will come round to and accept my Word.” But he never does.

Perhaps Hart’s most astounding assertion is that there is nowhere in the letters of St. Paul so much as a hint that some of God’s rational creatures may not be, finally, saved; that some of them may suffer eternal punishment in hell (86). He maintains, for example, that 1 Corinthians 3:11–15 mentions “only two classes of the judged: those saved in and through their works, and those saved by the fiery destruction of their works” (96). Hart takes this to mean that everyone is saved one way or another. Read in context, however, the passage is not about the final judgment of all of humanity; it is, rather, Paul demanding that the fractious Corinthians stop identifying themselves as followers of Paul or followers of Apollos or of any other evangelist, for all are servants of Christ.

Even stripped of its context in a letter to a particular people regarding particular issues, the verses Hart cites hardly seem to establish his case with such force and clarity as he assumes, but when set over against numerous passages both in St. Paul’s letters and in the Catholic Epistles, in which the elect are sharply contrasted with the reprobate, the hope of salvation with the threat of perdition, eternal life with final destruction, such proof texts are altogether inadequate.

The minatory tone and the sharp contrast between “eternal life” and “wrath and indignation” is certainly not vague, obscure, or figurative; and the obvious inference is that the wrath and indignation are as eternal as eternal life. There is nowhere in Romans that adds qualification assuring us that all will eventually obtain salvation. Hart argues that this letter does, in fact, affirm universal salvation : “Even Paul dared to ask, in the tortured, conditional voice of the ninth chapter of Romans, whether there might be vessels of wrath stored up solely for destruction only because he trusted that there are not: because he believed instead that all are bound in disobedience, but only so that God might finally show mercy to all” (69, citing Rom. 11:32).

But the anguish afflicting Paul in chapter 9 is for his fellow Jews, for whose sake he would himself willingly be accursed (anathema); and it is this dilemma that is resolved in chapter 11, where the apostle says that his preaching to the Gentiles may provoke emulation (zeloso) among the Jews (v. 14), so that some (tinas) may be saved, if they do not continue in unbelief (v. 23: ean me epimenosin te apistia). Paul maintains that Jews may still be saved, and, according to some interpretations, saved according to their original covenant, because God’s gifts and call are irrevocable

(v. 29). It is hardly clear that the salvation of individuals is the issue here. Verse 32, which Hart cites, does indeed say that God has confined all men to disobedience so that he may show mercy to all, but there is no assurance here that all will accept mercy, and there are numerous passages, in addition to those already adduced, which at least put the matter in doubt.

The Early Christian Writings

Hart’s assertion that there is no mention of eternal damnation “in the earliest Christian documents of the post-apostolic church, such as the Didache and the writings of the ‘Apostolic Fathers’ and so forth” (107), is undermined by a swift perusal of these texts. In the Didache, for example, a Greek work written toward the end of the first century, the writer warns that unless one remains active in the Christian community, “the whole time of your faith shall not profit you except you be found perfect at the last time.” During these final days, he adds, “then shall the race of men come into the fire of trial, and many shall be offended and shall perish; but they who endure in their faith shall be saved from under the curse itself” (16, Schaff translation). One might object that the text does not explicitly say that the faithless will perish forever, but it does not say they will not; and the urgency of the warning is difficult to explain otherwise.

Among other apostolic fathers, the evidence is even more damning, shall we say, to Hart’s assertion that the early Eastern Church universally accepted universalism. In the Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians we are warned about “the coming judgments”: “For where can any of us escape from his strong hand? And what world will receive any of them that desert from his service?” (28). And again, “it is better for you to be found little in the flock of Christ and to have your name on God’s roll, than to be had in exceeding honor and yet be cast out from the hope in him” (57).

In what used to be thought Clement’s second epistle, now called “An Ancient Homily by an Unknown Author,” we are warned that if we do not do the will of Christ, “then nothing can save us from eternal punishment” (6); and we must repent now: “For after we have departed out of the world, we can no more make confession there, nor repent any more” (8). These are both Greek texts, written toward the end of the first or the beginning of the second century.

The same kind of implicit or explicit warnings about eternal punishment occur again and again throughout these earliest post-scriptural Christian writings. In the fifth of his seven letters (“To the Philadelphians”), St. Ignatius of Antioch warns schismatics that they “do not inherit the kingdom of God” (3). The Letter of the Smyrnaeans on the Martyrdom of St. Polycarp says that the martyrs “found the fire of their inhuman torturers cold: for they set before their eyes the escape from the eternal fire which is never quenched” (2); and St. Polycarp himself warns his tormenters that they are “ignorant of the fire of the future judgment and eternal punishment, which is reserved for the ungodly” (11).

But the real elephant in the room is surely St. John Chrysostom, than whom no one is more distinguished among the Eastern church fathers. Hart mentions Chrysostom only once: “John Chrysostom (c. 349–407) once even used the word aiōnios to describe the reign of Satan over this world precisely in order to emphasize its transience, meaning thereby that Satan’s kingdom will last only till the end of the present ‘age’” (111–112). We have already noted, however, that the word aiōnios can have different meanings, and, in any case, Hart simply ignores numerous instances where Chrysostom deploys the term in a way that clearly suggests eternal punishment.

A powerful example comes in his Exhortation to the Fallen Theodore, who is admonished not to think of the fires of hell as like fire in this life. In this world, fire eventually consumes what it burns, “but that fire is continually burning those who have been seized by it, and never ceases; and therefore it is called unquenchable [āsbestos].” In this state, Chrysostom continues, body and soul will abide together “in a state of eternal punishment [aionīos kolazōmenon].” There is no “end” or “goal” (peras) beyond this (10). It is difficult to see how St. John Chrysostom could be more emphatic, and this is just one of many passages. The “unquenchable fire” and “eternal punishment” occur in his Commentary on Matthew, Sermons XI (7,8) and LV (6); in his Commentary on John, Sermon XVIII (1); and in his treatise concerning the Christian priesthood (III,7; IV,6; VI,13).

Why the Urgency?

There is, then, no dearth in Scripture, in the earliest post-biblical Christian documents, or among the fathers of the Eastern Church on affirmation of the eternal punishment of unrepentant sinners. It is astonishing that Hart can assert the contrary with such breezy assurance. Still, what is most remarkable is Hart’s apparent indifference to the urgency expressed both by the New Testament and the saints that the gospel be preached and sinners be brought to faith and repentance throughout the world.

In the Gospel of Matthew, as soon as the Infancy Narrative is completed, we are presented with St. John the Baptist sternly preaching repentance and warning of the coming judgment carried out by the Messiah: “Whose fan is in his hand, and he will thoroughly cleanse his floor and gather his wheat into the barn; but the chaff he will burn with unquenchable fire” (3:12). This Gospel ends with our Lord’s command to the apostles, “Going therefore, teach ye all nations; baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost” (28:19).

Both the Acts of the Apostles and St. Paul’s letters mention again and again his extraordinary labors and sufferings on behalf of the gospel and the salvation of the Gentiles, and all the apostles save one die as martyrs to its propagation. The history of the early Church is, likewise, an account of the suffering and death of her numerous martyrs—that is, witnesses—to the necessity of preaching the gospel of salvation to the heathen. Evangelization has remained, ever since, at the heart of the Church’s mission, and generation after generation of Christians have sacrificed worldly success, comfort, health, and their very lives to this same proposition.

If everyone will eventually be saved anyway, what is the point?

Misunderstanding Heaven

The rejection of hell, of the concept of eternal condemnation, seems to follow in tandem from a misapprehension of the nature of heaven and the meaning of eternal salvation; that is, those who are offended by the idea of hell have, perhaps, not fully grasped or appreciated the idea of heaven.

St. John Henry Newman offers a cogent insight in the first of his Parochial and Plain Sermons, written while he was still an Anglican:

. . . if we wished to imagine a punishment for an unholy reprobate soul, we perhaps could not fancy a greater than to summon it to heaven. Heaven would be hell to an irreligious man. We know how unhappy we are apt to feel at present, when alone in the midst of strangers, or of men of different tastes and habits from ourselves. How miserable, for example, would it be to have to live in a foreign land, among a people whose faces we never saw before, and whose language we could not learn. And this is but a faint illustration of the loneliness of a man of earthly dispositions and tastes, thrust into the society of saints and angels. How forlorn he would wander through the courts of heaven! He would find no one like himself; he would see in every direction the marks of God’s holiness, and these would make him shudder. He would feel himself always in His presence. He could no longer turn his thoughts another way, as he does now, when conscience reproaches him. . . . God cannot change His nature. Holy He must ever be. But while He is holy, no unholy soul can be happy in heaven. (loc. 361)

Heaven, that is, provides none of the consolations that we fancy to be available in sin: a man who dies regretting that he has not succeeded in fornicating with all the women who provoked his lust will not find his desires slaked in the presence of the holy God. You may sooner expect a man who has despised Mozart and Haydn and spent his days riding around in an oversized pickup truck with rap blasting from the speakers to welcome an eternity spent in Covent Garden.

“If a certain character of mind,” Newman continues,

a certain state of the heart and affections, be necessary for entering heaven, our actions will avail for salvation, chiefly as they tend to produce or evidence this frame of mind. Good works (as they are called) are required, not as if they had any thing of merit in them, not as if they could of themselves turn away God’s anger for our sins, or purchase heaven for us, but because they are the means, under God’s grace, of strengthening and showing forth that holy principle which God plants in our heart, and without which (as the text tells us) we cannot see Him. (loc. 361)

The text that Newman is expounding in this sermon is Hebrews 12:14: “Holiness, without which no man shall see the Lord.” It is not that God will not admit us into heaven because we have done evil, or because we have not done good, or have done too little; rather, it is because the evil we have done, and the good we have left undone, have rendered us incapable of entering heaven; that is, the presence of the Holy God.

The Hell of Self

Poets have sometimes intimated this notion more effectively than many theologians. Christopher Marlowe’s Mephastophilis replies, when Dr. Faustus inquires about the location of hell, “Hell hath no limits, nor is circumscribed / In one self place; for where we are is hell, / And where hell is, there must we ever be” (Doctor Faustus, Scene 5:120–122). Milton’s Satan, having been permitted to escape the confines of the cosmic hell to which he and the other fallen angels have been condemned, admits, likewise, that the essence of hell is not the place, but his own sinful nature:

Me miserable! which way shall I fly

Infinite wrath, and infinite despair?

Which way I fly is Hell; myself am Hell;

And in the lowest deep a lower deep

Still threat’ning to devour me opens wide,

To which the Hell I suffer seems a Heav’n.

(Paradise Lost IV:73–78)

These confessions by devils, conceived by later poets, help explain what is at first one of the most puzzling and unsettling passages in the greatest poem on the subject. Dante tells us (in Anthony Esolen’s translation) that inscribed over the gates of hell are these lines: “JUSTICE CAUSED MY HIGH ARCHITECT TO MOVE: / DIVINE OMNIPOTENCE CREATED ME, / THE HIGHEST WISDOM, AND THE PRIMAL LOVE.” When God created heaven as the complete expression of his love, he necessarily created hell for those creatures who reject love and thus bring hell with them wherever they go. Hence the final line of the inscription: “ABANDON ALL HOPE YOU WHO ENTER HERE” (Inferno III:4–6,9).

The ultimate sin, or perhaps condition of sinfulness, is despair, because a soul that does not love God has no alternative to the heaven of his love except the hell of self. Or as Gerard Manley Hopkins puts it in one of the “terrible sonnets”: “Selfyeast of spirit a dull dough sours. I see / The lost are like this, and their scourge to be / As I am mine, their sweating selves; but worse.” Touchstone readers will doubtless recall the most vivid twentieth-century version of this account of perdition, C. S. Lewis’s The Great Divorce.

Our only means of understanding how our destiny unfolds in eternity is to consider it in analogy with our earthly experience. Hart deals cavalierly with the substance of literature, maintaining, for example, that we are merely “bewitched by the beauty of Dante’s verse and the majesty of his narrative gifts” (22) into taking his representation of eternal punishment seriously.

The One We Can Judge

Finally, if our Lord’s stricture that we must not judge lest we be judged means anything, it means that we must not presume to determine another man’s eternal destiny. There is, however, one individual whom we are permitted, nay, commanded, to judge, not merely with respect to particular actions and opinions, but in ultimate terms and with rigor: namely, ourselves. I am disinclined to discuss myself in composing an argument on a controversial subject, but in this instance it seems necessary. Hart insists that no rational man can truly believe in eternal punishment, that such belief is merely a dogmatic delusion, or else a pathology of some souls who want to believe in hell, because

it gives them a sense of belonging to a very small and select company, a very special club, and they positively relish the prospect of a whole eternity in which to enjoy the impotent envy of those writhing, resentful souls that have been permanently consigned to an inferior neighborhood outside the gates. (28)

Prescinding altogether from Hart’s dubious judgment of his neighbor, I shall assert with complete candor and conviction that I never brood upon the eternal destiny of others: not Judas, not Hitler, not Stalin, not the mean teacher I had in the fifth grade. Although I am sometimes anxious about the choices of relatives and friends, I remember them in my prayers and paradoxically—Hart might well call it a contradiction—leave them to the mercy of our good God.

No, the only man whose possible impenitence I ever consider, the only one I ever imagine in hell, is myself. Scrutinizing my conscience, I find no difficulty—to my intense shame—imagining my own final rejection of God’s mercy. Although my list of idolatrous “loves” would be different, the protagonist of Walker Percy’s Love in the Ruins is to me quite “relatable,” to use the current argot: “I believe in God and the whole business but I love women best, music and science next, whiskey next, God fourth, and my fellowman hardly at all. Generally I do as I please” (6).

Far from relishing the prospect of my enemies’ eternal misery, it fills me with anxiety, since it seems to make my own perdition more likely. I know many men and women who are more virtuous than I, few whose vices are undoubtedly worse than mine, and when I consider the abundance of advantages, gifts, and blessings that I have enjoyed, there seems to be no excuse for that stony lump of pride nestled in the core of my ego. In Dana Gioia’s poem “The Seven Deadly Sins,” Pride, having dismissed the six other capital sins, closes with this insinuating offer:

But stick around. I have a story

that not everyone appreciates—

about the special satisfaction

of staying on board as the last

grubby lifeboat pushes away.

Reflecting on the role of the Titans in Greek mythology, men ought to have been more circumspect about naming a ship Titanic. If your conscience acquits you of any resonance with these literary passages, then you are much to be envied—or pitied.

Too Great a Cost

David Bentley Hart does allow for the possibility of a purgatory where God cleanses man of his sin before his inevitable salvation, but one might well wonder whether this god is not quite as much a monster as the God that Hart rejects. If our suffering in this world, our struggle against evil in the world and sin in our own souls, does not finally matter, if our “fear and trembling” are, finally, a sham, not really a factor in our ultimate salvation, isn’t God then the perpetrator of a cosmic practical joke of, at best, dubious taste?

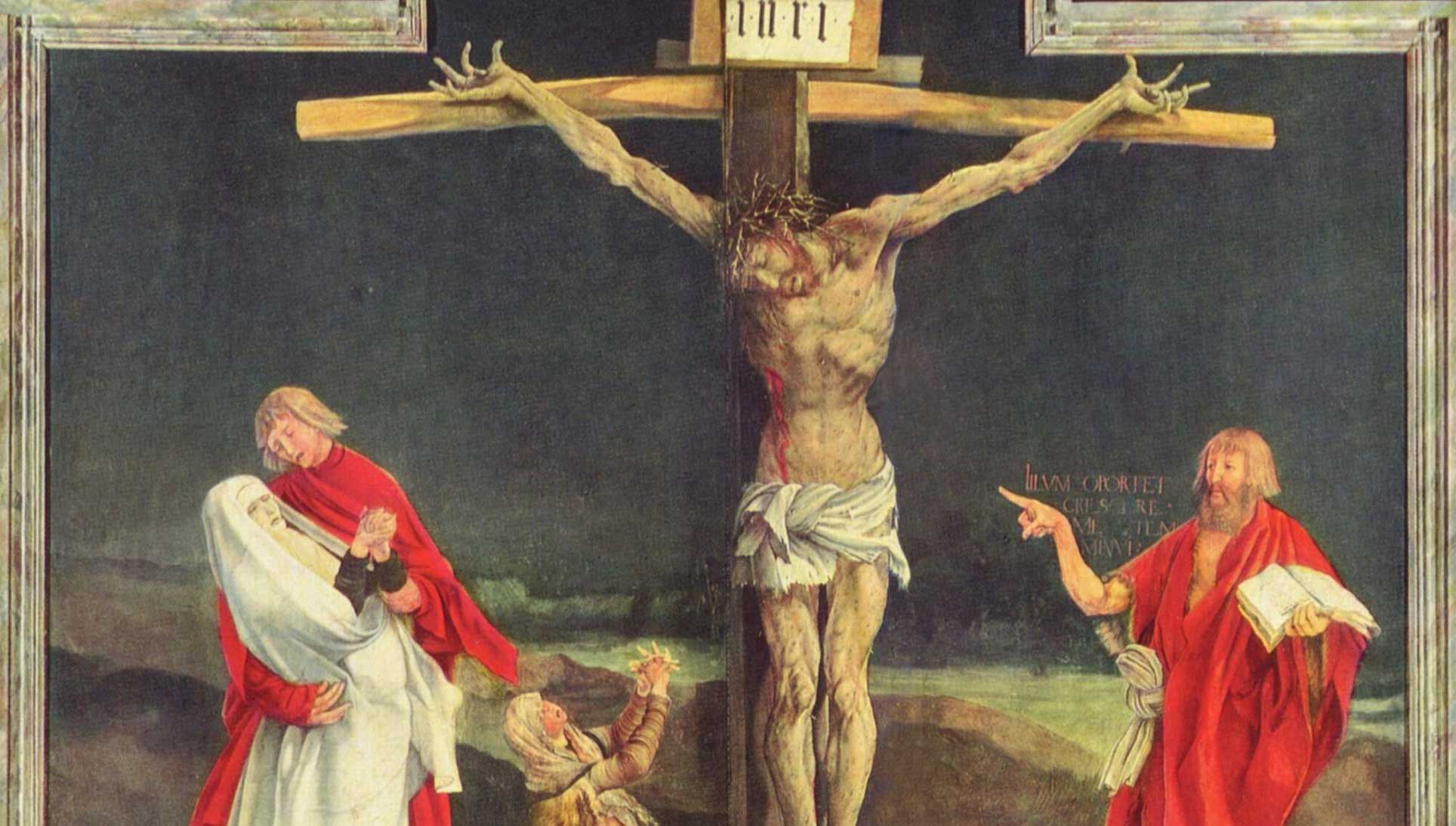

If we are not free to reject God’s gracious love, why are we put through the misery of sorrow, failure, war, natural catastrophe, grief . . . ? The list is endless. And why did Jesus of Nazareth die an agonizing, humiliating death on the Cross, if nothing that any man ever does, or if whatever he finally becomes in this life, does not ultimately matter?

In order to produce an idea of God that comports with a modern rationalist notion of what God ought to be and how the destiny of mankind ought to unfold, David Bentley Hart offers us an abstract deity who created a race of rational creatures whose earthly lives are inconsequential. It is also a depiction of reality that has little to do with the drama and mystery of sacred Scripture or with the epic tale of the Church in history. We may devoutly hope and pray for the salvation of all men, but to assume that it is a certainty costs far too much.

R. V. Young is Professor of English Emeritus at North Carolina State University, a former editor of Modern Age: A Quarterly Review, and the author of Shakespeare and the Idea of Western Civilization (Catholic University of America Press, 2022). He and his wife are parishioners at St. Ignatius of Antioch Church in Tarpon Springs, Florida. They have five grown children, fifteen grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

11.5—September/October 1998

Speaking the Truths Only the Imagination May Grasp

An Essay on Myth & 'Real Life' by Stratford Caldecott

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor