Feature

Virtue Gone Mad

Victimhood Culture Scapegoats Its Very Source

It was Harvey Mansfield who voiced the notion that you can tell who is in charge of a society by noticing who is allowed to get angry and for what cause. Donald Trump certainly gets angry, but given the chilly disdain for his splenetic tweets and polemical rhetoric, it does not appear that he is allowed to by those "in charge of our society." The U.S. Catholic hierarchy and other Christian leaders, on the other hand, seem to be acutely aware of the Mansfield principle, and thus they avoid public displays of righteous anger unless the cause is likewise promoted by those "in charge"—for example, social justice issues.

So who, then, is in charge? Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning provide a partial answer to that question in their 2014 article in Comparative Sociology, "Microaggression and Moral Cultures," and in their 2018 book The Rise of Victimhood Culture: Microaggressions, Safe Spaces, and the New Culture Wars (Palgrave Macmillan). The authors' thesis is that the embrace of victimology that began in the 1960s and 1970s has given rise to a new "culture of victimhood." Like any other moral culture, victimhood culture offers a framework for resolving conflict and awarding praise or blame. But in crucial respects, victimhood culture is unlike any other, past or present.

Honor & Dignity

To highlight its distinctive features, Campbell and Manning contrast victimhood culture with two other cultures from American history: the "honor cultures" of the American Revolution and antebellum South, and a "dignity culture" that reached its height in the Midwest in the 1950s.

In honor cultures, men are highly sensitive to insult (hence the prevalence of duels). They like to call attention to themselves, especially to their prowess or exploits in areas involving conquest or risk, and they like to do so not only with respect to virtuous acts of bravery but also with respect to vicious acts such as gambling, drinking, and philandering. Honor seekers do not hesitate to exaggerate their successes or even lie about them, for by maintaining the appearance of being a victor in conflicts, they maintain their status and intimidate competitors. Honor cultures are tight-knit communities where word of mouth and age-old custom prevail and where supervening legal authority is disdained. Men of honor may love their family and their country, but they scorn the government or the court system, for there is more glory in resolving conflict through one's own skill or bravery than by invoking the help of a third party.

In a culture of dignity, on the other hand, individual dignity is seen as an inherent and inalienable good that one does not need constantly to prove or assert as in an honor culture. Consequently, in a dignity culture it is considered unnecessary and distasteful to draw attention to oneself. Insults no longer provoke wrath as they do in an honor culture: the phrase "Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me" nicely sums up a dignity culture but is unthinkable in an honor or, as we shall see, victimhood culture. Dignity cultures have a stable and powerful third-party legal system, but the goal is to use such a system as quietly, discreetly, and as rarely as possible. Self-restraint, toleration, and peaceful confrontation are the hallmarks of a dignity culture.

Competitive Victimhood

A victimhood culture, by contrast, is an almost perfect photographic negative of an honor culture. Like honor cultures, victimhood culture is highly sensitive to insult. Today this sensitivity is enshrined in the use of terms like "microaggressions" and "trigger words," but the phenomenon predates the jargon. In the 1990s, Danusha V. Goska was a leftist when she read a passage from Caroline Myss's bestselling Anatomy of the Spirit. Myss, Goska later wrote,

described having lunch with a woman named Mary. A man approached Mary and asked her if she were free to do a favor for him on June 8th. No, Mary replied, "I absolutely cannot do anything on June 8th because June 8th is my incest survivors' meeting and we never let each other down! They have suffered so much already! I would never betray incest survivors!" Myss was flabbergasted. Mary could have simply said "Yes" or "No."

Reading the anecdote was an epiphanic moment for Goska, who immediately recognized the same proclivity to outrage among her leftist friends and allies.

I felt that I was confronting the signature essence of my social life among leftists. We rushed to cast everyone in one of three roles: victim, victimizer, or champion of the oppressed. We lived our lives in a constant state of outraged indignation. I did not want to live that way anymore. I wanted to cultivate a disposition of gratitude. I wanted to see others, not as victims or victimizers, but as potential friends, as loved creations of God. I wanted to understand the point of view of people with whom I disagreed without immediately demonizing them as enemy oppressors.

As Goska's observation attests, while touchiness in a victimhood culture is as pronounced as it is in an honor culture, the content could hardly be more different. To put it in the language of our current President, honor culture extols "winning" while victimhood culture dwells on "losing." Unlike a dignity culture, both honor and victimhood cultures encourage their members to call attention to themselves. But whereas people in an honor culture like to mention their own exploits, in a victimhood culture they prefer to mention their own hardships, to vocalize what they suffer at the hands of others on account of their race, class, or gender—and if they qualify as a victim in all three categories, they are eligible for an even more prestigious status according to the logic of "intersectionality."

In such a cultural setting, so coveted is the status of victim and so despicable that of oppressor that there even emerges what Campbell and Manning call a culture of "competitive victimhood," where individuals often exaggerate or lie about their level of victimization or their membership in a historically victimized group in order to obtain the status they seek. Hence the rise of "hate crime hoaxes," where individuals fabricate stories of being attacked by members of an oppressor group, as in the infamous 2006 Duke lacrosse case, where three white members of Duke University's lacrosse team were falsely accused of raping a black woman. Hence also the proliferation of "phony memoirs," fabricated or plagiarized accounts of oppressed people's trauma written in the first person by relatively privileged whites whose identification with the oppressed often borders on the pathological. And hence the remarkable case of Rachel Dolezal, the woman who feigned being black and falsely claimed that she was the victim of nine hate crimes before it was discovered that she was a blue-eyed blonde from Montana. Dolezal received a good deal of criticism for her duplicity and was forced to resign from her leadership position in the NAACP, but her motives are understandable in a culture that privileges victims.

Victimhood cultures thrive in highly egalitarian societies, where the only kind of "deviance" left to be despised is not manifesting cowardice or moral depravity but speaking or acting against equality or diversity. Such cultures also thrive where there is a high degree of social atomization, that is, where individuals are no longer tightly bound to family or clan or other stable groups that serve as intermediaries between them and the rest of society or the government. Like a dignity culture, victimhood culture requires a superior third party, such as a college administration or the federal government; but unlike members of a dignity culture who would rather not "make a scene," victimhood status seekers or their agents pursue a "squeaky wheel" policy, loudly pressuring a third party, through protests or public shaming, to side with the alleged victim group and condemn their ostensible oppressors. Indeed, while the honor-seeking man or woman can live without the interventions of a third party, members of a victimhood culture cannot.

Dangers of Victimhood Culture

Every arrangement for doling out recognition has its strengths and weaknesses. The obvious strength of a victimhood culture is that it embraces and consoles victims. Victims of rape, for example, might be inclined to "hide their shame" in an honor culture, but in a victimhood culture they are rightly considered innocent of any wrongdoing and encouraged not to feel any self-recrimination for the terrible ordeal they have suffered.

But victimhood culture also has its weaknesses. First, as in an honor culture, it is too easy in a victimhood culture to confuse a genuine desire for justice with the desire for self or group promotion. The temptation in a victimhood culture is to jockey for power and recognition by portraying oneself or one's group as a victim regardless of important distinctions that are essential to civic justice. Keeping (transgendered) men out of women's restrooms, for example, is not the same as keeping blacks out of white restrooms, even though both groups have been accorded victim status.

Second, defining oneself as a victim can prevent an individual from attaining self-knowledge, since he (or she) thinks he already knows who he is. But no matter how much a person has been victimized, he is always more than a victim—he is, as Goska intimated, an image of God. In victimhood cultures, self-knowledge is easily replaced with self-pity, and self-pity, as the novelist John Gardner is reputed to have said, is "the most destructive of the non-pharmaceutical narcotics; it is addictive, gives momentary pleasure, and separates the victim from reality."

Third, and similarly, victimhood culture discourages a deeper quest for truth, because the painful, disorienting, and humiliating quest for truth is replaced with the desire to protect victims from all "microaggressions," even the ones that may happen to be true. Hence, on many college campuses today, the older model of education as a challenging tournament of ideas, in which egos can get bruised, has been replaced by a newer model in which education becomes a comforting therapy session guaranteeing high self-esteem among the students.

Fourth, a victimhood culture encourages a heightened and untenable fragility. In an article entitled "Colleges Are Promoting Psychological Frailty and We Should All Be Concerned," Dr. Clay Routledge contends that "victim protection campaigns many colleges are engaged in not only underestimate human resilience, they may actually cause the problems they are designed to solve because they suggest to students who wouldn't otherwise feel like victims that they are, in fact, victims." This identification as victims undermines their natural capacity to remain "psychologically healthy in the face of offensive Halloween costumes, distasteful jokes or comments, and sensitive course material." Or as Steve Maraboli is reported to have said: "The victim mindset dilutes the human potential. By not accepting personal responsibility for our circumstances, we greatly reduce our power to change them."

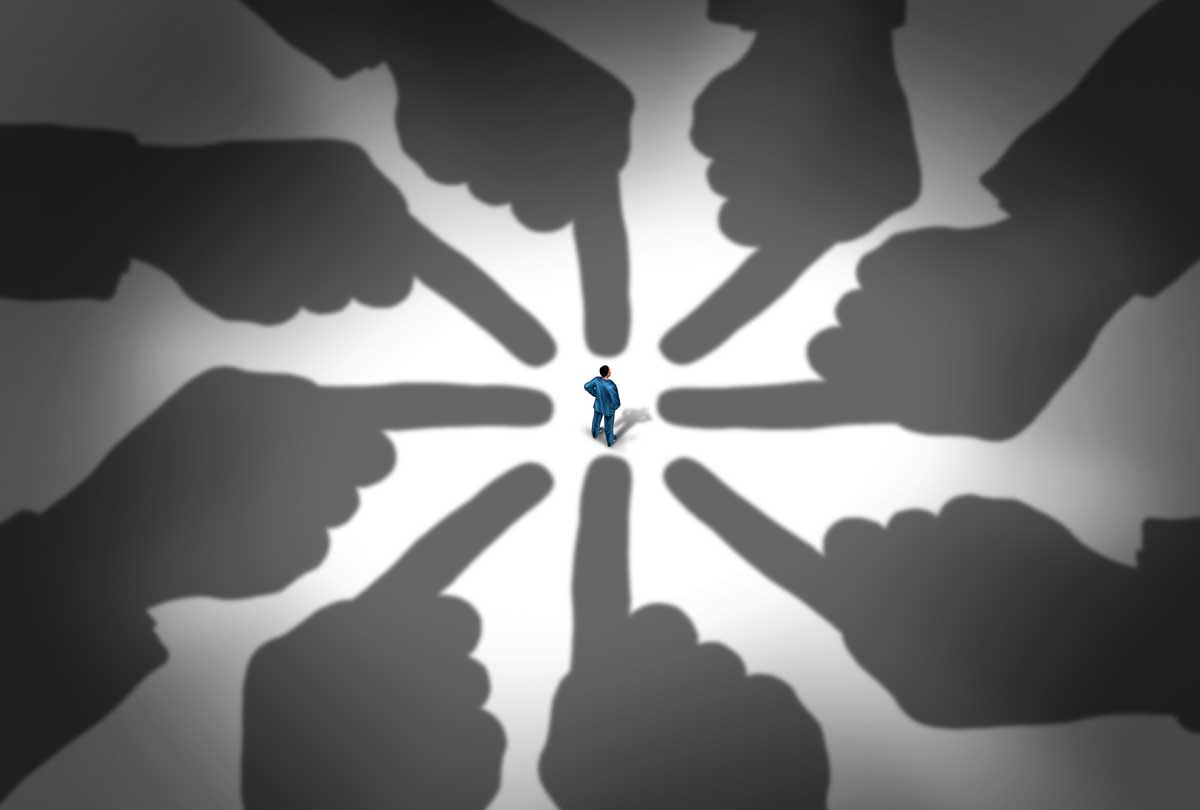

Fifth, the combination of social atomization, social media, and victimhood culture creates conditions that easily lead to witch hunts and other forms of hysteria that ruin the careers or lives of innocent people. Just ask Justine Sacco, who (in)famously became the object of mass hatred and lost her job because of one stupid tweet that went viral. Instead of protecting alleged victims, victimhood culture can create real ones.

Sixth, with its reliance on superior third parties, victimhood culture increases the power of those parties, further weakening intermediary groups and individual rights. Hence today we see the increasing power of college administrations and the decreasing power of faculty, the increasing power of the federal government and the decreasing power of counterbalancing associations such as churches, clubs, and so forth. The danger of giving these third parties, which tend to be vast and impersonal bureaucratic organizations, so much power was expressed well by President Gerald Ford: "A government big enough to give you everything you want is a government big enough to take from you everything you have."

Finally, as the power of these third parties expands, a phenomenon that sociologist Donald Black calls "legal overdependency" may develop, in which individuals become increasingly unwilling or unable to use other forms of conflict management. A generation or two ago, Americans generally knew how to settle their differences among themselves, either by confronting each other directly or through the intervention of neighbors or a local clergyman. Today, it is more common to immediately take recourse to social media, the police, and the courts. Campbell and Manning note that legal overdependency thrives especially in totalitarian societies such as Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union, where citizens' denouncing each other to the law became an effective if brutal way of resolving their private disputes.

The combination of an increase in government power with a decrease in other forms of conflict resolution is particularly dangerous when a third element is added: an increasing intolerance of views deemed microaggressive. According to a 2015 Pew poll, 40 percent of Millennials, the generation most imbued with the culture of victimhood, thought that it was proper for the government to prevent citizens from making statements that minority groups would find offensive. By contrast, only 12 percent of the so-called Silent Generation (Americans between the ages of 70 and 87) thought the same way. To put it cynically and I hope with exaggeration, victimhood culture makes tempests out of teapots and then requires the expansion of tyrannical powers to quiet the storm.

Trumpism versus Victimism

One of the advantages to Campbell and Manning's concept of a victimhood culture is that it explains much of the animosity directed at President Donald Trump. I say "much" because I am in no way suggesting that Trump is above criticism; rather, I am suggesting that with phenomena such as the histrionic "buttercup" reactions to the presidential election, we are witnessing in American society not simply a disagreement over principles or policies but a fundamental clash of cultures.

The "braggadocious" Trump is in many respects a classic exemplar of the honor culture but with an American corporate twist. Hostile takeovers have replaced military conquests, and a gaudy display of wealth has replaced the badges and battle scars that once made others hold their manhood cheap; yet the distorted exaggerations about one's exploits (including vices such as womanizing) remain the same, and so too does an indifference to truthfulness. Trump's own narrative of success and triumphant confrontation, which he exults in telling and retelling, is diametrically opposed to the victimologists' narrative of exploitation and victimization. It is as if Trump and his haters were speaking two different languages.

And there is an additional reason for promoters of a victimhood culture to oppose Trump's presidency. As we have noted, a culture of this kind relies heavily on legal authority as a third party that can vindicate its grievances and award it the coveted status of victim. Trump's victory in the 2016 election, however, means that the executive branch of the United States is now headed by someone who does not operate out of the same framework and who is staffing the federal government with others who share his point of view.

Victimologists rightly felt that Barack Obama was sympathetic not only to their claims but also to the concept of "dominance" as the only remaining form of deviance. Trump, on the other hand, delights in his dominance as a sign of his worth. Champions of victimhood culture are worried, and not without good reason, that one of the legs of their stool is being kicked out from under them.

Christianity & Victimhood Culture

As we will see in a moment, victimhood culture is especially congenial to the New Left and is now actively promoted by it, but the culture of competitive victimhood has become so intoxicating that it has even affected conservatives, such as the men who respond to feminist denunciations with charges of "reverse sexism" or the Princeton student who in 2007 fabricated a story about being beaten for his rightwing views.

Such responses are not effective. As Campbell and Manning note, victimhood culture is concerned "with offenses against minority or otherwise less powerful cultures, not offenses against historically dominant ethnic groups such as whites or historically dominant religious groups such as Christians"—even when those groups are currently being victimized. Muslims qualify as victims because they are seen as the innocent targets of Western hatred and intolerance stretching from the First Crusade to Fox News—this despite the fact that Islam has markedly illiberal attitudes towards other "victim groups" such as women, homosexuals, and the transgendered, and despite the fact that Islam itself facilitates a virulent honor culture. Martyred Christians in the Middle East, on the other hand, do not receive the same sympathetic attention or recognition because even though they have been a persecuted minority since the seventh century, they are lumped in with white Christians as "historically dominant." It also doesn't help that these Christians are being slain by a group whom victimologists insist are victims and not oppressors.

But there is a twofold irony in disqualifying Christianity from victimhood status, and it is this: (1) there would be no cultural concern for the victim were it not for Christianity, and (2) the secular Left's attack on Christianity for being oppressive is not only inaccurate as a whole but also a form of scapegoating.

Regarding the first point: Before Christianity, myths and the cultures that made them assumed that the victim was guilty and therefore never took the victim's side even when, weirdly enough, they later worshiped the victim as a god. First Judaism and then Christianity changed all that. Many of the Psalms record the voice of an innocent victim scapegoated by an angry mob, and the Gospels proclaim the innocence of Jesus Christ, a fact known both to his disciples and to his persecutors, who sacrificed him out of fear that the whole nation might perish (see John 11:50). Christianity exposes once and for all the satanic nature of scapegoating an innocent person or minority group for the sake of political vitality.

Scapegoating continued to exist after Christianity and was even perpetrated by Christians themselves, as the sad treatment of Jews in the Middle Ages attests. But because cultures influenced by Christianity acknowledge that scapegoating is wrong, those who engage in it must be more subtle and self-deceiving than they were before; they must convince themselves that they are not scapegoating when in fact they are.

Enter the New Left's culture of victimhood and our second point. On one hand, the New Left has taken over Christianity's concern for the victim; on the other, it has turned this concern against Christianity, heavy-handedly portraying it as oppressive. This, at least, is the position of René Girard in his powerful monograph I See Satan Fall Like Lightning (Orbis Books, 2001). As Girard puts it, the Left's new "totalitarianism" reproaches Christianity "for not defending victims with enough ardor. In Christian history they see nothing but persecutions, acts of oppression, inquisitions."

This new totalitarianism "presents itself as the liberator of humanity," but in fact it is trying to demonize the one religion that delivers humanity from the darkness. Girard goes so far as to call the Left's new victimology a kind of Antichrist, for it apes the teachings of Christ while ushering in something quite different:

The Antichrist boasts of bringing to human beings the peace and tolerance that Christianity promised but has failed to deliver. Actually, what the radicalization of contemporary victimology produces is a return to all sorts of pagan practices: abortion, euthanasia, sexual undifferentiation, Roman circus games galore but without real victims, etc.

Whither the Nation

Even if Trump wins a second term as president, I doubt that his chest-thumping style of leadership is likely to impress #MeToo-ers and halt the advance of victimology in this country. The real drama will be between victimhood culture and mere Christianity. In its proclamation of the one True Victim who has taken on our guilt and shame, Christianity has the capacity to create a culture that is based on neither self-pitying victims nor arrogant victimizers; and it can speak to the deepest concerns of a victimhood culture while purging such a culture of its shortcomings. The question is whether victimologists will see this as well and change their ways, or continue on their current path.

Christianity began with the recognition that Jesus was an innocent victim and that the many were guilty; the Left now increasingly teaches that the many are innocent victims and that Jesus and his followers are guilty. Beneath the current Christ-like slogans of tolerance, diversity, equality, and, above all, concern for the victim, does there lurk the cry of "Crucify him"? It will be interesting to see what happens next if this new and unpurified paradigm of victimology is the only voice allowed to get angry.

Michael P. Foley is an associate professor of Patristics in the Great Texts Program at Baylor University and the author of The Politically Incorrect Guide to Christianity (Regnery, 2017).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor