Illuminations

When Worship Goes Wrong

by Anthony Esolen

One of my hobbies is to collect and read bound editions of my favorite all-purpose magazine, The Century, which saw its heyday in the 1880s and 1890s. For its intelligence, breadth, and variety of matter—serialized novels by Mark Twain, Henry James, and William Dean Howells, alongside Civil War memoirs and articles on religion, politics, history, culture, world exploration, and the natural sciences—it is utterly unlike anything in our experience now. The Century was also markedly Christian and “progressive,” in a time when that adjective implied measures that would strengthen the family rather than subordinate it to large economic interests or to government at any level.

The editors at The Century took music seriously, and that included sacred music, too. Music was not mass entertainment, for the simple reason that the technology for the latter did not yet exist. I read there with a twinge of guilt the opinion that Mr. Edison’s “talking machine” might extend the reach of great music farther than ever, so that we might attend to two different renditions of Wagner and compare them for their merits. Yes, we can do that. For the most part, though, we put our fantastic technology in the service of trashy stuff. I don’t mean what is workmanlike but does not rise to brilliance; I don’t mean the work of that mysterious fellow whose paintings we find in rural medieval churches all over Europe, that good old Pictor Ignotus. I mean trash, the stuff that smells.

Robinson’s Complaint

Trash wasn’t what the Reverend Charles S. Robinson was complaining about in a series of three long letters to the editors at The Century (February, March, and April 1884).It was something like the reverse: misplaced virtuosity, when organists and choristers would commandeer a Christian service. Sometimes the result was comical. Robinson recounts an incident on Easter Sunday. The pastor had urged the people to open their wallets to defray the last expenses on their recently refurbished church. An inspired call, says Robinson, worthy of a rousing hymn to follow! And so it did, in the voice of a hired German singer with hard consonants, singing, “Ant the det shall be raised, ant the det shall be raised!”

More often the results were infuriating or disheartening, depending upon your temperament or whether you were the minister or a mere suffering member of the congregation:

Once I preached on exchange for a neighboring minister. In that congregation the organist was the leader of the choir, and hence was responsible for the music altogether; and he had ordinarily his way. The opening piece occupied, by the time-piece directly fronting me on the organ case, seventeen minutes. During this performance we all sat and patiently listened, or watched each other impatiently; we had nothing to do with selecting it, with singing it, or with understanding it. Then I was at liberty to commence divine worship with the customary prayers of the people. After this a hymn was offered to the congregation, the verses of which were driven hopelessly apart by an interlude of wonderful construction on the instrument. The organist paused deliberately after each stanza, leaving us to stand and watch him, while in leisurely silence he contemplated the position, decided what, under the circumstances, he would do, then pulled out such stops as he deemed the fittest for his present venturous undertaking, and, when he got ready, went on to play a strain of interlude as far away as perverse ingenuity could invent from the chosen music which was printed before us in the book.

Take away the virtuosity, and replace the grand organ with electronically amplified guitars and drums, and there you have a contemporary “worship team” or “music ministry” or something, turning the worship of God into their own American Idol show.

A Perennial Problem

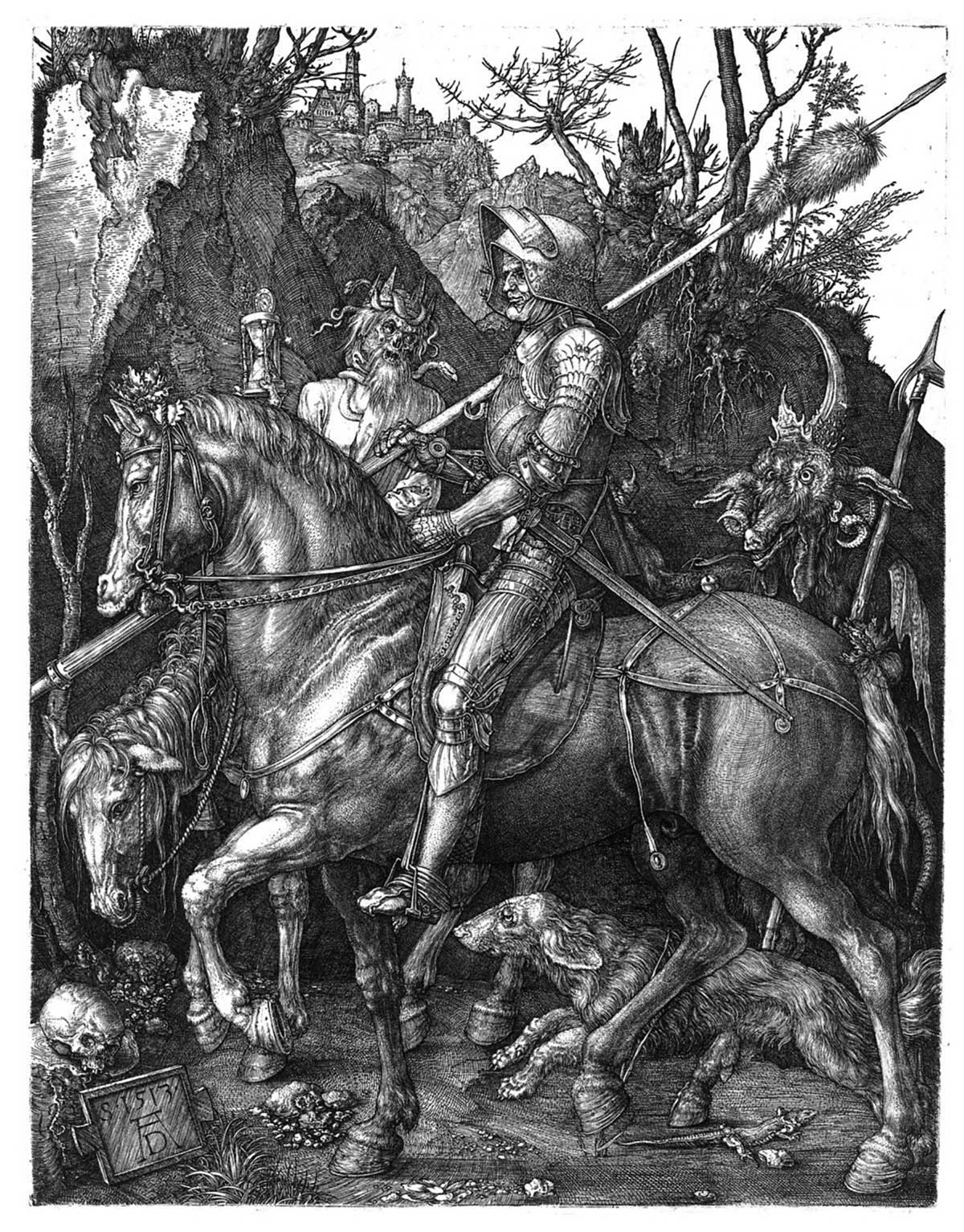

It is, as I say, not a new problem, because man is man—headstrong, selfish, and vain. Robinson observes that during the Council of Trent, the bishops came near to decreeing that only the simplest of Gregorian chants might be sung in the house of God, lest worship be overwhelmed by artistic performance; and here were Protestants, three centuries later, coming near to banishing the pipe organ, for much the same reason.

I will not say that because the organ can be used badly for congregational singing, therefore the guitar can be used well. I don’t think it can be. The large space of a church tends to muddy its notes, even supposing that the player is not just picking chords. The melody cannot be heard from the instrument, and the full range of human voices, from bass to treble, can find no fit overtones to guide them. But all instruments, even those most fit for the acoustic and human situation of a church service, can be used badly, if they are not subordinated to the act of worship in its full liturgical context.

At this point I suspect that most church musicians and choristers will judge themselves to be free of sin, and I don’t want to suggest that they are anything like the arrogant organist Robinson described. Yet I beg them to consider. I will speak about the church I know, the Roman Catholic. In almost every American and Canadian Catholic church I have been to, the hymns are chosen by the music committee, not by the pastor. That is a mistake. Very few of the hymns chosen will have anything to do with the liturgical season, or with the readings for the day, or the saint to be commemorated; if they do so as much as one fourth of the time over the course of a year, you are doing well.

The choir chooses the hymns because they like them and believe that they perform them well; at least they are used to them. That means that you actually hear a repertoire of twelve or fifteen hymns, over and over, outside of special hymns for Advent, Christmas, and Easter. The choir sings. In the congregation, no man with a bass voice sings—how is he going to find his note when the chief sound he hears is a soprano? And why would he sing effeminate, contemporary, show-tune ditties anyway—Jesus jingles? The more compliant sex sings, sort of; some do, some don’t, and most of those who do, sing rather quietly. Children fidget, and teenagers suffer or smolder in silence.

That is supposed to be the double-prayer that Augustine calls the singing of sacred song?

One Pivotal Question

The entire discussion, says Robinson, turns on one question:

whether the choir, the organ, the tune-book, and the blower are for the sake of helping God’s people worship Him, or whether the public assemblies of Christians are for the sake of an artistic regalement of listeners, the personal exhibition of musicians, or the advertisement of professional soloists who are competing for a salary.

Allow me to translate into our contemporary terms. If the people do not sing, something is wrong. If what is played and sung is pretty much the same from Sunday to Sunday, and does not cover the great range of Scripture and of man’s experience of God, something is wrong. If in any conceivable way the players and the singers are seen as performing, rather than assisting in prayer, whether sung prayer or prayer in silence, something is wrong.

We are not supposed to “worship by proxy,” as Robinson puts it, and so “it is not unkind or ungracious to inform many of our musical friends that the usual assemblies of religious people do not have any sympathy with artists in their rivalries for place or emolument,” let alone with neighbors who have sometimes a higher opinion of their talents than is justified. Let us sing, O music directors—please, permit us to sing, and to sing hymns worthy of our solemn worship.

By the way, Reverend Robinson knew whereof he wrote. He published a widely disseminated collection of hymns, and wrote many of his own. My readers will have heard of at least one: “Nearer, My God, to Thee.”

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor