Feature

Millennial Mission

The Transmission of Christianity Is Not a New Task

by Nathanael Devlin

As a child I was captivated by sacred stories of lostness. My ears perked up in church at a retelling of the lost sheep, the lost coin, or the lost son. These parables played on my imagination in a deeply formative way. They were serious, urgent, and required resolution. There was something precious about what was lost that caused pain in the one who lost it. These parables conditioned me to be on the lookout, to seek and to find that which was lost. The urgency of the stories created urgency in me.

In my adult years I have been given the privilege of serving Christ’s church as a pastor in the Evangelical Presbyterian Church. My role gives me opportunities to seek that which is lost and to nurture within the church a compassion for lost things. Being a pastor also puts me in contact with many other pastors and with denominational superiors. In addition, I stay fairly up-to-date with the news and keep an eye on what is being said by Evangelical leaders, ministries, and publications seeking to impact the world for Christ today.

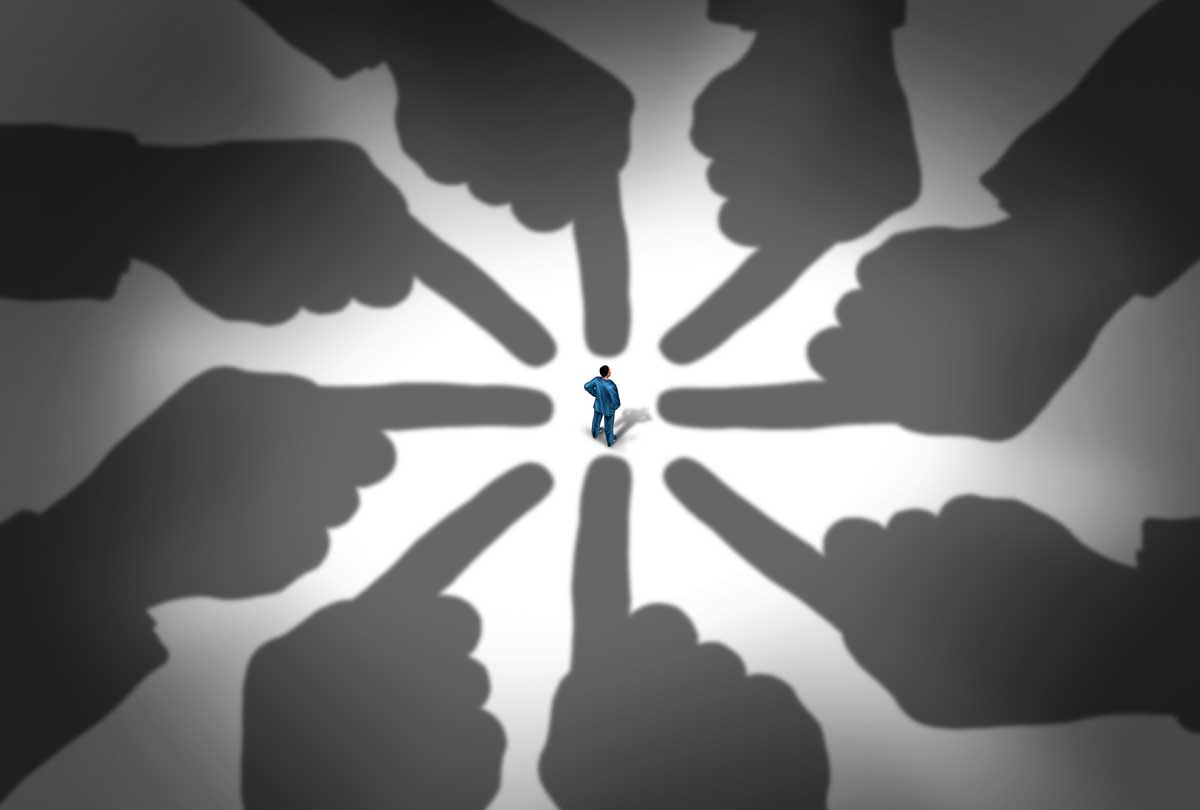

With increasing regularity, I have been hearing from colleagues and the larger Evangelical world about growing concern over a particular category of lostness that they suggest is unique to this age—the absence of millennials in Evangelical churches. With this concern there appears to be an attending nervousness that is growing, producing impassioned pleas on the part of church leaders and millennials alike to have churches reevaluate and even retool their ministries so as to make them more attractive to the millennial demographic. The church needs to respond to this situation decisively and persuasively, they tell us; not doing so will be catastrophic for the future of the church.

But what is the nature of this new category of lostness? Is our concern truly for lost sheep, lost coins, and lost children? Or might it be that these voices, in a moment of urgency, are summoning us to a great quest—a quest they say is ordained by God—to seek after something that, in the end, may not really be out there?

Who Are the Millennials?

According to the Pew Research Center, millennials are those who were in the 18–34 age range in 2015. They have eclipsed the 74.9 million baby boomers (ages 51–69 in 2015) of America to become the nation’s largest demographic, according to population estimates released by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The Barna Group, in a 2014 study titled Americans Divided on the Importance of Church, paints a bleak picture of the future of the church in America, telling us that “Millennials stand out as least likely to value church attendance; only two in 10 believe it is important. And more than one-third of Millennial young adults (35%) take an anti-church stance.” The study goes on to list some of the reasons why millennials are opting out of church:

35% cite the church’s irrelevance, hypocrisy, and the moral failures of its leaders as reasons to check out of church altogether. In addition, two out of 10 unchurched Millennials say they feel God is missing in church, and one out of 10 senses that legitimate doubt is prohibited, starting at the front door.

These numbers are indeed alarming, but perhaps more alarming are the observations and reflections of self-identified millennials themselves. Sam Eaton is one; his article, “12 Reasons Millennials Are Over Church,” went viral in September 2016. Eaton laments the fact that so many millennials are absent from the church, but he also wonders why churches simply continue with business as usual rather than searching for this lost generation. To aid the church, he writes, he is metaphorically nailing “12 theses to the wooden door of the American, Millennial-less Church.” He offers what he believes to be solutions, but in the end he concludes that the church has put its head in the sand:

It’s obvious you’re not understanding the gravity of the problem at hand and aren’t nearly as alarmed as you should be about the crossroads we’re at. You’re complacent, irrelevant and approaching extinction. A smattering of mostly older people, doing mostly the same things they’ve always done isn’t going to turn the tide. Feel free to write to [sic] me off as just another angry, selfy-addicted millennial. Believe me, at this point I’m beyond used to being abandoned and ignored.

There are others, however, who recognize that the church has not ignored the problem of the missing millennial. Rachel Held Evans, another self-identified millennial, wrote a Washington Post op-ed in 2015, entitled “Want millennials back in the pews? Stop trying to make church ‘cool,’” in which she acknowledges some of the changes churches are making to draw her cohort back to worship. The only problem, she says, is that the church’s approach is often wrong:

[M]any churches have sought to lure millennials back by focusing on style points: cooler bands, hipper worship, edgier programming, impressive technology. Yet while these aren’t inherently bad ideas and might in some cases be effective, they are not the key to drawing millennials back to God in a lasting and meaningful way. Young people don’t simply want a better show. And trying to be cool might be making things worse.

In sum, according to Evans, the church has good intentions but often employs bad strategies, which come from not fully understanding the nature of the problem.

Taken together, the data from statisticians, analyses from Evangelical leaders, and expressed opinions of millennials themselves paint a very sobering picture that cannot be ignored. But the church’s strategies must be commensurate with the problem at hand. There is no sense in lighting a lamp and diligently sweeping up the house if what we are looking for is lost sheep far from home. So, to foster a better understanding of the problem and of the sort of strategies that might effectively address it, I offer the following observations.

Abstracting Millennials

While millennials do make up a large proportion of the U.S. population and their absence is keenly felt within the church, the term “millennial” itself, which the culture uses to designate them, has become an abstraction that obscures the real people behind it and the real problems facing both them and the church. The ramifications of this abstraction are profound. The “millennial” has taken on an elusive and mythical aura, like that of unicorns, leprechauns, and the Holy Grail.

We have become fascinated, even obsessed, with millennials; we hear that they are out there, but we don’t know how to find one. So we marshal resources and people to search them out; we develop new programs and slick advertising to attract them; we position our nets and cages in the hopes of seeing and maybe catching some. Noting the magnitude of this group within the general population and its enormous potential for power and influence, we wonder, “How can we leverage this group for the church?” Millennials have become like a magic oil lamp in our minds: if we can just get our hands on it and rub it, we can get the genie to pop out and grant us all our ecclesial wishes.

It is always easier to think about people in abstract terms rather than as concrete realities. But Eugene Peterson, one of the modern church’s wisest voices, warns us in his book Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places against using language and terms that reduce people to abstractions. For instance, a term like “resource,” he writes,

identifies a person as something to be used. There is nothing personal to a resource—it is a thing, stuff, a function. Use the word long enough and it begins to change the way we view a person . . . it erodes our sense of this person as soul—relational at the core and God-dimensioned.

Similarly, abstracting millennials reduces them to resources to be mined in our Evangelical expeditions.

Abstractions adversely affect our mission and our programs. When we make abstractions of millennials, they become the future of the church, so we must divine what appeals to them and develop new programs accordingly to lure them in. But again Peterson observes, “The attractiveness of a program is that it simplifies by depersonalizing: get everyone doing the same thing for the same goal.” It is easier to develop a new program than to minister grace to a sinner, and that is exactly what a millennial is: a sinner in need of the reconciling love of Jesus Christ, just like the rest of us. There is no mystery here, so there is no need to radically alter the mission of the church.

Millennials Are Begotten, Not Made

In 2005 Christian Smith published Soul Searching, a groundbreaking study of the religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers. In this study Smith discovered that the dominant religion among current U.S. teenagers is “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism” (MTD). MTD is a religion that holds to the belief that there is a distant god out there who simply wants everyone to be nice to each other and for everyone to be happy. Smith describes MTD as a parasitic faith with no integrity of its own. It must feed on the established traditions of historical religions like Christianity and Judaism to survive and grow. But it changes and distorts the theological substance of those traditions in order to create its own distinctive theological and religious viewpoint.

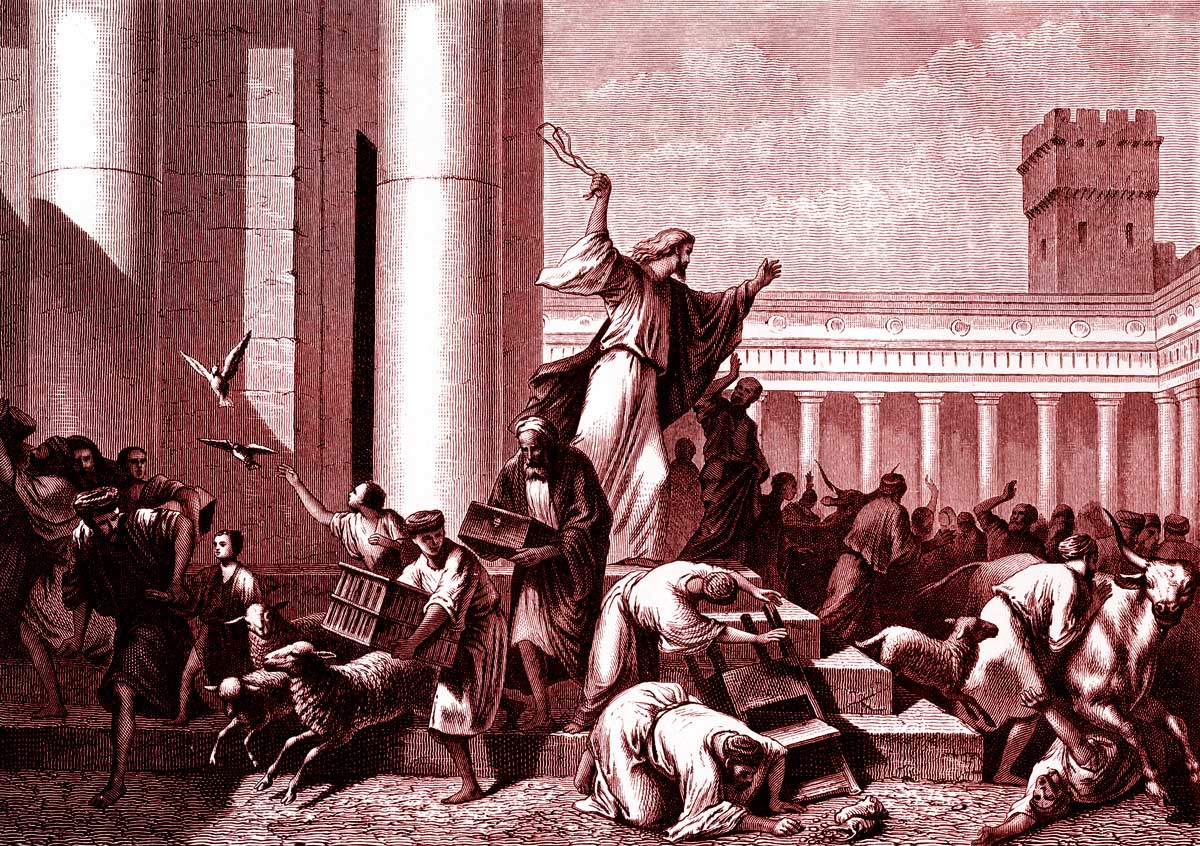

Today, more than twelve years after Smith published his book, we are seeing the full flowering of MTD within the millennial demographic. The theological, ecclesial, and spiritual identity of a whole cohort of young men and women has been hollowed out and refashioned into a faith of their own making and in their own image. Should the church be surprised, then, to find millennials demanding that its ministries, programs, and practices be changed to accommodate their own perceived spiritual needs and desires? Of course not, nor should we feel obliged to react to their demands. Have we never before heard the command, “Up, make us gods who shall go before us” (Ex. 32:1)?

But more important than the discovery of MTD as the default religion of American teenagers is the fact, stressed by Smith, that MTD is not limited to teenagers. “On the contrary,” he writes, “it seems that it is also a widespread, popular faith among many U.S. adults. Our religiously conventional adolescent seems to be merely absorbing and reflecting religiously what the adult world is routinely modeling for and inculcating in its youth.”

The sobering truth is that millennials’ religious perceptions and dispositions did not emerge ex nihilo but were in fact begotten by their spiritual parents. It is the baby boomer who gave birth to the millennial. It was the boomers who crafted church in their own image, making it more casual, more “seeker friendly,” more entertaining. Millennials watched their precursors take down the cross to make room for the screen; they saw them eliminate the liturgy to increase “praise time”; they heard them talk about how important it was for God to make them feel better about themselves rather than about sin and the need for repentance—and now the shoe is on the other foot. I am reminded of a 1987 public service announcement, sponsored by the Partnership for a Drug Free America, in which a father confronts his son after finding a box of drug paraphernalia among his things. The father bursts into the teen’s room and angrily asks him how he learned to use drugs, and the son shouts back, “You, all right?! I learned it by watching you!”

The One Thing Needed

This cycle must be broken. To do so, the church needs to insist on being the church, on maintaining its integrity and handing down the traditions that have been informed by the apostolic doctrine once and for all delivered to the saints.

A lesser-known essay by C. S. Lewis,entitled “On the Transmission of Christianity,” is instructive here. The piece served as a preface to B. G. Sandhurst’s 1946 book, How Heathen Is Britain?, which examined the educational system in England in the 1940s and how well (or poorly) it educated the college-age men of the time in the Christian faith. The book is a precursor of sorts to Christian Smith’s work. In his preface, Lewis offers several wise and helpful observations that are relevant to our modern millennial concern.

First, he notes that Sandhurst’s research clearly showed that many 18-to-22-year-old men were not Christian simply because the educational system did not plainly put the case for Christianity before them. But when the case was put before them, the young men were open to the claims of Christianity, and many found them believable. Lewis suggests that this revelation puts the lie to the reasons offered by experts for the decline of religion, which are so often advanced and so readily believed in our day as they were in his. He writes:

Where a clear and simple explanation completely covers the facts, no other explanation is in court. If the younger generation have never been told what the Christians say and never heard any arguments in defense of it, then their agnosticism or indifference is fully explained. There is no need to look any further: no need to talk about the general intellectual climate of the age, the influence of mechanistic civilization on the character of urban life. And having discovered that the cause of their ignorance is lack of instruction, we have also discovered the remedy. There is nothing in the nature of the younger generation which incapacitates them for receiving Christianity. If any one is prepared to tell them, they are apparently ready to hear.

Lewis’s thesis has the ring of truth. It is simple, profound, and incredibly liberating for the church. If Lewis is right, there is no need to twist ourselves into knots trying to divine what millennials want, because we already know what they need. We don’t have to invent new programs, either fashionably modern or ancient, or rebrand or reimagine anything. Let us not waste time and energy on new measures or techniques. The one thing needed is a clear and robust ministry of the gospel. In churches where worship is offered in its purity and integrity, where discipleship is conducted with clarity and affection, where fellowship is enjoyed with hospitality and regularity, and where stewardship is practiced sacrificially and faithfully, there will the mission of the church be attractive and fruitful, not just to millennials but to people of all ages.

Comedy or Tragedy

It is tragic that so many millennials are missing from our churches, but it is equally tragic that so many congregations have sought to accommodate themselves to the felt needs of the “demographics” outside the church and to the “solutions” offered by those within. If we continue down this road, the church will in time become just an amusing spectacle to the world. Future generations will either chuckle at us as we feverishly update our image to be more in sync with current sensibilities or, worse, they will simply ignore us.

Nathanael Devlin is the Associate Pastor at Beverly Heights Presbyterian Church (EPC) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He is a graduate of Trinity School for Ministry in Ambridge, Pennsylvania. He and his wife have three children and live in Mt. Lebanon.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor