Column: A Thousand Words

The Portinari Altarpiece

by Hugo van der Goes

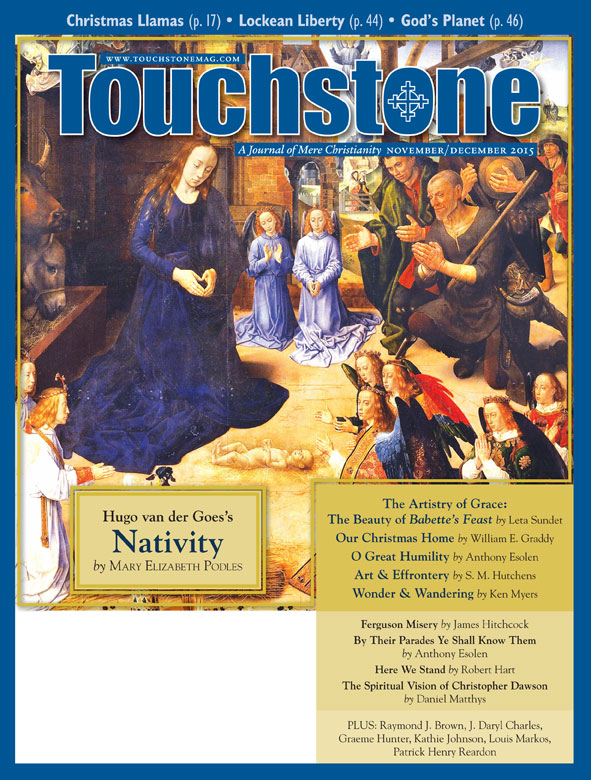

In 1476, Tommaso Portinari, the Medicis' banking agent in Bruges, commissioned this triptych for the main altar of the Church of Sant'Egidio in Florence. Three years and many miles later, it took sixteen strong men to deliver it: it is eight feet high and just over nineteen feet long when opened. The painter, Hugo van der Goes, has followed the traditional three-panel format, with a sacred scene, here the Adoration of the Shepherds, flanked by wings depicting the donors and their patron saints, who present them to the Lord.

(enlarge)

The work is, however, anything but conventional. Though he was fully versed in Renaissance anatomy and spatial construction, Hugo willfully breaks the Renaissance canon of unity and reverts to a medieval hierarchy of scale. The saints, Anthony and Thomas in the left panel and Margaret and Mary Magdalene in the right, are much bigger than, and out of scale with, their namesakes the Portinaris: Antonio and Tommaso, Margherita and Maria Maddalena (the younger boy, Pigello, was born while the painting was in progress, and was added in without benefit of patron saint). Since the saints are bigger, we read them as more important; they are drawn to scale with Joseph, Mary, and the shepherds, and belong therefore to the heavenly realm.

They are also set apart spatially. The Portinaris occupy the front plane of the picture, and are closest to the real space outside the frame. In the central panel, the division between earthly space and sacred space is clearly demarcated: Joseph, like Moses before him, has removed his shoes because he is standing on holy ground. Mary is at the center. The fifteen angels (surely a reference to the fifteen mysteries of the rosary), the shepherds, and Joseph form a circular frame around her, and an inner circle of holy ground on the floor plane separates her from them. All the perspective lines of the architecture—the beams, the edges of the capitals—point to Mary's face, and her gaze leads, as always, to Jesus.

If the painting's space leads in to the center, so too, curiously, does its time. Hugo also ignores the unities of time. In the background of the left-hand panel, a tiny detail shows Mary and Joseph on the way to Bethlehem; Mary, unable to ride further, leans into Joseph's arms while the donkey trails behind (detail 1). Similarly, in the right-hand panel, there is a scene from the near future: the three kings, already en route (detail 2). And in the back of the center panel is a scene from the immediate past: angels making the annunciation to the shepherds, who then enter the stable as in a photographic time-lapse sequence: bursting in, pausing, quieting, and falling to their knees in recognition of the mystery (detail 3).

These three rustics, incidentally, were another unconventional touch. They were admired for their realism, and it was remarked at the time that this was one of the first admissions of the common man into a scene of high holiness. It therefore was recognized as an exceptional statement of the solidarity and the brotherhood of man.

Look a little more closely at the center towards which all time and space converge. At the center lies the baby Jesus (detail 4). If this is such a masterpiece of observed realism, why has his mother laid him on the cold stone floor? Because at the time, an educated worshiper would have recognized the stone slab as a reference to the Stone of Anointing, on which Christ was laid after the Crucifixion. The overall mood of the painting is a somber one: this is a foreshadowing of the Pieta. Christ's passion and death are contained even in the joy of his nativity.

A Window into the Holy

There is more. Originally, the picture hung over an altar, and not in the Uffizi as it does today. Ordinarily, the two side wings were folded shut, showing an Annunciation painted in monochrome, like a fictive sculpture. During Mass, the wings were swung back to reveal the full-color scene inside, as if opening a window onto another reality, that of the supernatural world.

The illusion is made more real by the flowers set at the front plane of the center panel: they are painted very naturalistically, as if they were actual flowers set on top of the high altar (detail 5). But they also carry symbolic freight. A knowledgeable audience would have been able to read their language: for example, in contemporary poetry, the columbine stood for sorrow; seven columbine blossoms would represent the seven sorrows of Mary. Similarly, the iris is the sword lily, and stood for the sword of sorrow that pierced her heart at the Crucifixion, while the scarlet lily stood for the blood of the Passion, and the carnations for the Crucifixion itself. (The derivation of flower symbolism is sometimes oblique. Carnations smell like cloves; cloves look like nails; nails remind us of the Crucifixion.) Violets, scattered along the ledge, are low-growing and sweet, and stand for humility, both Mary's and her Son's.

Behind the flowers sits a sheaf of wheat, a reference to Bethlehem, the "house of bread," where Ruth, gleaning, met her future husband and thus became an ancestor of Christ. A tiny harp in the archway above Mary's head (detail 6) refers to David: this is the ruined palace of the House of David, which gives legitimacy to Christ's claim to be the Messiah. The wheat sheaf carries a further weight of symbolism, and would have been recognized both as a reference to Christ as the first fruits of redemption, and to the Eucharist.

The angels who kneel to either side of the wheat are drawn to the same scale as the patrons; that is to say, they belong to the earthly region, to our space. They transition us from real time and real space into the holy place at the center. Furthermore, they are vested as priest, deacon, and acolytes, as if to participate in the real-time Mass that takes place at the altar. It is in the Mass, then, says the painter, that we impinge upon the eternal order, celebrate the Incarnation, reenact the Passion, partake of the bread of angels, and open a window onto the divine. •

Mary Elizabeth Podles is the retired curator of Renaissance and Baroque art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. She is the author of A Thousand Words: Reflections on Art and Christianity (St. James Press, 2023). She and her husband Leon, a Touchstone senior editor, have six children and live in Baltimore, Maryland. She is a contributing editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on art from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor