Feature

Ferguson Misery

History, Theology & Mythmaking from a Deadly Encounter

by James Hitchcock

A year ago the modest-sized suburban community of Ferguson, Missouri (population 21,000), achieved a worldwide infamy that seems likely to endure for decades, the very name of the town having become shorthand for a myth that goes far beyond what actually happened there.

The verifiable core of the myth was the death of Michael Brown, an 18-year-old black man and Ferguson resident who had an altercation with a white police officer, Darren Wilson, as Brown was walking in the middle of a street. What exactly happened is unclear, but during the altercation Wilson shot Brown to death.

The first level of mythologizing was the claim that Brown, a "gentle giant" who had no criminal tendencies, was shot in cold blood as he was running away from Wilson. But as the investigation unfolded, it turned out that Brown was facing towards the policeman and, according to some accounts, lunging towards him when he was shot. Just prior to the incident, Brown had strong-armed a clerk in a convenience store and stolen a pack of cigars. He had also been using marijuana. Brown's alleged last words—"Hands up! Don't shoot!"—became the principal mantra of the developing myth, but Brown almost certainly did not utter them.

For days afterwards there were riots, both in Ferguson and other parts of the St. Louis area, with much of Ferguson's business district destroyed. (The liberal governor of Missouri, Jay Nixon, after first promising help, ordered the National Guard to remain passive as stores were torched and looted.) In April 2015, nine months after Brown's death, mobs again surged through Ferguson looting and burning, supposedly in protest of the killing of a black man in Baltimore.

Before there was reliable information as to what had actually happened to Brown, there were enraged demands—backed by threats—that Wilson, who went into hiding and later resigned from the police force, be charged with murder, and there was further rioting when a grand jury found no grounds for indictment. (Eventually the federal Justice Department reached the same conclusion, but even that did not end the demands that Wilson be punished.)

Justifying the "Protestors"

From the beginning, Brown's enraged supporters in effect denied the principle "innocent until proven guilty." Despite confused accounts, it was taken as fact that Wilson was a murderer, an assumption that was shared by much liberal opinion, led by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, which only slowly and reluctantly scaled back its account as more information became available.

Dorian Johnson, another "gentle giant," who was with Brown when he was killed, was the principal source of stories about the shooting, but his testimony was found to be completely inconsistent with the physical evidence. (Months later he was arrested and charged with drug dealing and resisting arrest.)

The St. Louis County circuit attorney, Robert McCulloch, who presided over the grand jury investigation, was proclaimed to be biased, on the grounds that his father was a policeman who had been killed by a criminal. McCulloch was also denounced for making available to the public much of the grand jury testimony, virtually none of which supported the Brown myth. Liberals spoke of "the failures of the grand jury process to indict the police officers involved," and law professors took to the pages of the Post-Dispatch to explain that it was the business of grand juries to indict people, not to exonerate them. When McCulloch spoke at St. Louis University Law School, his alma mater, he was treated rudely.

The media consistently used the word "protestors" to refer to the mobs that surged through the streets burning and looting, although the sheer terrorism quickly became too obvious to ignore.

Among other things, two "protestors"—one of whom had spoken from the pulpit of a Ferguson church—eventually pled guilty to attempting to obtain bombs to blow up St. Louis's Riverfront Arch and other buildings, and to planning to kill some prominent person "and then at his funeral we gotta get a couple more—'Godfather' style." A young white man plotted to steal guns to sell to "protestors," and two Ferguson policemen were hit by shots fired from within a gathering of "protesters."

A shocking claim in the Brown mythology was that his body had been desecrated by being left in the street for hours after he was killed. Only belatedly did the public learn that mobs had blocked ambulances and fire trucks from reaching the scene. (Ironically, the Post-Dispatch won a journalism award for a photo of a thug hurling a fire bomb, although the paper had been reluctant to acknowledge the degree to which naked thuggery far overshadowed ostensibly high-minded "protests.")

Mantra versus Reality

Although ultimately perhaps only religion offers a means of overcoming the deep divisions in society, in this case some of those who spoke in the name of Christianity demonstrated that religion can in fact be a barrier against both understanding and healing. Their theologizing removed the case from the realm of history and made it into yet another epiphany of a timeless pattern of fated recurrences.

A Catholic nun composed a "Lamentation for Ferguson (and all other communities living with mistrust and fear)," asking,

How much longer do parents have to live under bone-crushing suspicion that their children will be accused of wrongdoing when out on the street? How much longer do parents have to continue burying their children while being unable to fully grieve since there are more deaths and more children to lay to rest? How much longer will neighborhoods have to wait who have a basic human right for safety?

"Black lives matter!" was a mantra in the case, but it seemed to make little difference to the "protestors" that, as many people pointed out, while the Ferguson riots were featured every day on the front page of the Post-Dispatch, it was necessary to look at the inside pages to learn that blacks were also being killed by one another every day, for reasons that were rarely evident and that seemed to manifest an extremely casual view of the value of black lives.

It was a reality for which no one seemed even to have an explanation, much less a cure, and each murder was almost immediately forgotten, partly in order not to distract attention from the Ferguson myth. These daily black-on-black killings are the principal reason why parents always have "more children to lay to rest," but the preferred story of the Brown case had no room for that stark fact. In the nun's "Lamentation" the story was the paradigm of all African-American lives: "Children" (of what age?) are "accused of wrong-doing" (are they ever guilty?).

Facts Don't Matter

In his book Racial Justice and the Catholic Church (2009), the African-American priest-theologian Bryan Massingale asked, "How much longer will neighborhoods all over this country, who are at the tipping point from continuing racial oppression and systemic misuse of power, hold on?" He claimed there is a "pervasive criminalization of black men," caused by white people's "largely unsubstantiated sense of threat and danger." (Before and during the Ferguson riots, the inside pages of the Post-Dispatch also regularly reported substantiated acts of violence directed by blacks at

whites.)

Massingale also spoke of "the current vilification of all illegal immigrants in Arizona caricatured as drug dealers and criminals." He ignored both the question of how accurate such "caricatures" might actually be and the fact that there are influential voices—Catholic bishops perhaps most of all—who passionately defend these immigrants. (The latter point could not be made because Massingale pronounced his church to be

"racist.")

The mythological nature of these theological reflections precluded any descent into mere history—it would complicate the myth to inquire too carefully. Massingale made the prohibition explicit:

While the circumstances of these shootings vary, and in some cases the judicial processes are still unfolding, there is a pattern here that is wrenching and disturbing. Perhaps, however, this pattern is seen only when one steps back from the particulars of specific situations and looks at the picture in its totality.

We are not to linger over cases. Facts don't matter.

Reviewing Massingale's book, the theologian Michelle A. Gonzalez, "a Cuban-American and self-proclaimed brown Latina," agreed: "We continue to get caught up in rational discussions of bias and prejudice, from which it is easy to distance ourselves, and fail to see the embedded and structural nature of racial injustice from which we cannot escape."

The issues are thus defined in such a way that there can be no solution. There were frequent calls to attack the "root causes" of these problems, but the claim that they are entirely the effects of a malign, systemic racism provides few handles by which those causes can be grasped. Deliberate racism is not the principal cause of black unemployment in a society that values education, nor does racism explain how black education is undermined. (Some months after the Brown incident, the Post-Dispatch took a close look at a school district near Ferguson and found a pervasive pattern of indifference and neglect on the part of students, teachers, and administrators alike, almost all of whom were black.)

Racist by Mere Existence

Citing Massingale, Gonzalez said that the Catholic Church in the United States is "a white racist institution where whiteness is normative for U.S. Catholicism. One only has to look at the demographics of Catholics in the pews and Catholics behind the altar (particularly bishops) to see the disconnect." Gonzalez added,

I agree with Massingale's claim that the institutional culture of U.S. Catholicism is white. If that weren't the case, why would the U.S. bishops' conference have cultural diversity subcommittees for African-Americans, Hispanics, Asian and Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans? Apparently, white or Euro-American Catholicism is not a dimension of U.S. Catholicism's diversity, it is normative.

This definition of racism has the effect of making it incurable. The Catholic Church would cease to be racist only if by some process whites were no longer a majority—their mere existence constitutes an injustice. (The committees to which Gonzalez objects were almost all formed in response to complaints that particular minorities were being ignored.)

In the inevitable competition for victimhood status, Gonzalez hit upon the fallacy without realizing it:

I must admit I was disappointed to find that Massingale's study limits his analysis to white and black racial groups, arguing that they are archetypal for understanding race in the United States. This may be the case if you are white or black. I am sympathetic to his argument yet feel that in the 21st-century United States to reduce race to whiteness and blackness is to oversimplify the lived complexity of racial identity in this country.

(Rather, one might say that Massingale's analysis flattens out the "lived complexity" of everyone's life and that Gonzalez's idea of "identity" is itself a distorting oversimplification.)

Archbishop Carlson's "Failings"

In an essay titled "Telling Tales: Ferguson and the Church" (Women in Theology, February 13, 2015), Katie Grimes, a feminist theologian living 900 miles from Ferguson in Philadelphia, was severely critical of Archbishop Robert Carlson of St. Louis: "White power, as Bryan Massingale notes, is mediated and sustained through structures and institutions, not just interpersonal actions. For this reason, he urges magisterial officials to move beyond the merely 'personal' in order to include what he terms 'the structural dimensions of the race question.'"

"Structural dimensions" seemed to go far beyond such things as discrimination in employment. Grimes found that

the Archbishop recognizes only those problems whose solutions leave white power and the underlying structural apparatus that support it intact: a vaguely worded pledge that the Archdiocese will "assist the churches in Ferguson and the surrounding area to deal with issues of poverty and racism"; a commitment to "establishing . . . the commission on human rights in the Archdiocese of St. Louis"; increasing the number of poor children able to attend Catholic primary and secondary schools; and offering a mass for Peace and Justice in every parish.

"In addition to assuaging the consciences of individual whites," Grimes charged,

this narrative also exonerates corporate bodies, like the church. In the Archbishop's story, he and his archdiocese are equipped, perhaps uniquely so, to be a part of the solution: he stands above the fray, an outside party come to adjudicate a nasty dispute. Styling himself a voice of reason, the Archbishop acts as a communal counselor, "urging anyone who feels the desire to violently lash out to first pause and consider the potential consequences of their actions." In this same vein, he positions himself as the leader of other leaders, "challenging . . . all religious, political, social, and law enforcement leaders [to] join him in asking the Lord to make us instruments of peace" and to provide "the courage in order to combat the brokenness and division that confronts us."

Grimes found the ultimate fallacy to be that

While the Archbishop denies the use of violence to the protesters, he does not deny it to the state. Law enforcement officers undoubtedly deploy violence in support of law and order. . . . I could find no statement from Archbishop Carlson chastising St. Louis' police officers for carrying a gun or baton or taser. Nor could I find any occasion on which the Archbishop exhorts Catholic members of the military to "reject any false and empty hope that violence will solve problems."

Without arguing the issue, Grimes seemed to require all Catholics to be pacifists. But it was a pacifism that, predictably, did not apply to "protestors." Grimes complained that,

Rejecting the spirit of the Civil Rights Movement, the Archbishop conflates peace with the absence of conflict. More than the Archbishop wants justice, he yearns for the restoration of a calm—or rather, pervasively white supremacist—social order. He asks that they "accept [the decision not to indict the killer of Michael Brown] as the proper functioning of our justice system."

(Presumably, if Officer Wilson had been convicted and punished, that would not have qualified as "state violence.")

Truth-Avoiding Methodology

Like Massingale and Gonzalez, Grimes forbade taking the discussion outside the boundaries of the mythology. Archbishop Carlson, she charged, employed "two common white supremacist talking points—'black on black violence,' and 'family breakdown,'" both of which, presumably, are merely white racist lies.

Grimes made explicit the mythologizing process: "We know white people by the stories they tell. . . . In recent weeks, many white people have relied on these stories to make sense of and defend themselves. They know they are good; their stories tell them so."

"Story-telling" is a favorite methodology of liberal theology, a genre that among other things avoids the question of how much truth a particular story contains. (Did Jesus really rise from the dead? His disciples told each other that he did.) In Grimes's account, white people are reduced solely to their race and seem not to be entitled to their own "story," which by definition will always be a distortion. (In fact, the infinite number and variety of "stories" told by and about white people represent white people in every conceivable way, from saintly to diabolical and everything in between. A course on "white literature from Homer to Joyce Carol Oates" would be sheer nonsense.)

The Heady Wine of Revolution

Predictably, the Brown case had the effect of revivifying—at least temporarily—the culture of "the Sixties," a welcome resuscitation for nostalgic survivors of that era and an unexpected taste of the heady wine of "revolution" for those who had had the bad luck of missing it the first time. Student "leaders" at local universities suddenly emerged as both experts on the Brown case itself and as stern arbiters of justice, while administrators groveled and instantly acceded to virtually all the student demands.

"Protestors" and self-defined "revolutionaries" swarmed to Ferguson from all over North America and even abroad, proclaiming that the "root cause" of the Brown case was "unjust systems that prey on the vulnerability of people, especially communities of color," an analysis that was (and was intended to be) literally global in its implications. One conference about Ferguson was cancelled when attempts were made to shift its focus to the "real" injustice in the world—the plight of Palestinians.

Writing from California on Truthout (December 3, 2014), David Theo Goldberg (a "professor of comparative literature and criminology") found that

the one encouraging outcome . . . revealed by events in and around Ferguson, is that youthful counter-activists are beginning to realize something novel is afoot. . . . They are increasingly engaging in a mix of now-you-see-me-now-you-don't performance interventions and potentially viral social media campaigns alongside the more traditional large-scale street protests. They are thus calling attention to and into question these conditions of sustained injustice at key sites of their sustenance: at elite cultural events such as the St. Louis Symphony, local city hall and state capitol. They are engaging in "die-ins" at popular, large local malls frequented more by whites than people of color.

(Surveying the scene from California, Goldberg added that "there are pretty much no malls remaining in Ferguson itself," without bothering to explain what had happened to them or reflecting on whether their destruction was of any benefit to the community.)

For Goldberg, the welfare of the community of Ferguson scarcely mattered, since it was merely a flashpoint in a new international movement.

It is likely that these sorts of activated responses and their global relation (there are already significant cross-references between Ferguson and Gaza) will gather steam as the repression extends itself, too. It remains to be seen whether such novel efforts will have more sustainable fuel and lasting effect to call attention to the ways in which "outbreak" racial events are structurally linked to each other in patterns of institutionalized racisms that continue to order the United States in less and less visible ways. Those concerned about these developments should do all they can to encourage and support these counter-measures.

As Goldberg exulted, Ferguson "protestors" demonstrated outside the homes of police and public officials, disrupted a performance of the St. Louis Symphony, and intimidated customers (including children) in shopping malls far from Ferguson. In Ferguson itself, meetings called to address problems were first disrupted, then boycotted. It was essential to sustain a crisis atmosphere, to forestall getting "caught up on rational discussions of bias and prejudice, from which it is easy to distance ourselves," as Gonzalez warned.

No Escape from the Myth

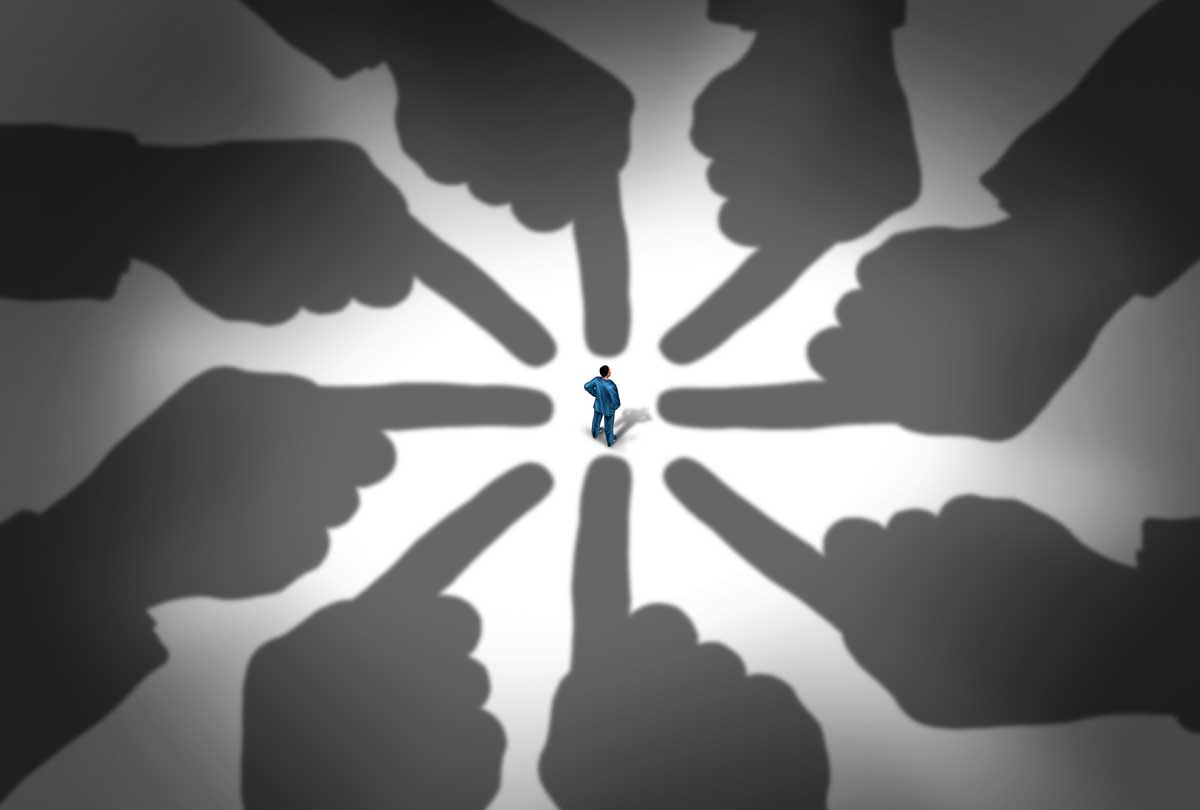

Would-be revolutionary movements always presage a kind of totalitarianism, because of the revolutionaries' conviction that their cause is so vital, so self-evidently just, that those who fail to support it are objectively the enemy. Disruptive intrusions of concerts and shopping malls are a kind of totalitarianism, a denial that there is such a thing as a private sphere—a "safe space"—apart from the political. Their aim is to create a climate of fear and confusion that makes people manipulable.

As during the Sixties, resistance is declared to be both illegitimate and unavailing, so that submission to the forces of history becomes mandatory. In April—nine months after Brown's death—mobs again surged through Ferguson, looting and burning, and three people were shot in the melee. Some carried American flags upside down and chanted, "We are the revolution. They can't stop the revolution." (Months earlier the Post-Dispatch had gloated, "Welcome to the revolution, Charles Krauthammer!" in mockery of a journalist who had committed the offense of subjecting the Ferguson myth to scrutiny.)

Gonzalez's phrase, "from which we cannot escape," is the ultimate point of the liberal mythology, which is intended as a device that holds white people fast no matter which way they may twist. But it does the same to black people, who are, in the long-familiar, white liberal way, also assigned a role that in effect denies their freedom to depart from the "story."

During the original Ferguson riots, a group of students at Washington University issued a list of demands that included a course on the realities of racism that would be compulsory for all students. The university immediately acceded to all the demands except that one, because it would have required faculty approval.

The demand for such a course demonstrated the ultimate point of the mythology that grew out of the Brown case, which was to forge a governing story that could henceforth be invoked in all situations: White people are not free and cannot be treated as such. Hopelessly blinded by self-delusion and self-interest, they can do nothing except submit to a severe tutelage that does not brook asking questions. The disruptions at the symphony and the shopping malls were reminders of the same demand: "You have no right to a life except insofar as it is submitted to our moral authority."

Inevitably left unexplained is how the self-appointed tutors have themselves escaped from the prison that constrains most other Americans, an escape that seems like the famous boast of the Pharisee in the Gospel, "Thank God I am not like the rest of men." Although liberals have long warned against those who "claim to have a monopoly in the truth," the nun's "Lamentation for Ferguson" prayed that, "when error is entrenched, may we proclaim truth."

Certitude Through Denial

Having repudiated "repressive" moral beliefs, especially those having to do with sex, liberal Christians cannot understand how evil is rooted in human nature but can only see it in terms of a mythologized politics. Grimes charged that,

For the Archbishop, the problem is not really racism but universally shared character flaws. In this way, he argues, "we need to keep in mind the issues here are bigger than Ferguson. They are as deep as the hold of sin on the human heart and as broad as the solidarity of the entire human race." Rather than singling out white people as uniquely culpable for and privileged by white supremacy, the Archbishop defines the situation as something for which white people bear no special blame.

The hate-filled burning, looting, and personal violence that erupted in Ferguson obviously went far beyond the particular incident that triggered them and served for some people as an opportunity to unleash a nihilistic lust to destroy. Leaders of "peaceful protests" lamented that violence would only make things worse, but their warnings were limp.

Pro forma condemnations of violence were also offset by such things as Grimes's warning that it is impossible to fight racism "without descending into chaos or submitting to turmoil" and that the church must "prefer the racial chaos that looks like violence to the white supremacist violence that passes for peace." In Baltimore, acting mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake announced that she "gave those who wish to destroy space to do that as well."

Liberal Christianity now has no purpose except that of making itself "prophetic" on every public issue. Having foresworn creeds, liberal Christians have gained dogmatic certitude about historical events, precisely by denying their historicity.

James Hitchcock is Professor emeritus of History at St. Louis University in St. Louis. He and his late wife Helen have four daughters. His most recent book is the two-volume work, The Supreme Court and Religion in American Life (Princeton University Press, 2004). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on culture from the online archives

more from the online archives

24.6—Nov/Dec 2011

Liberty, Conscience & Autonomy

How the Culture War of the Roaring Twenties Set the Stage for Today’s Catholic & Evangelical Alliance by Barry Hankins

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor