Feature

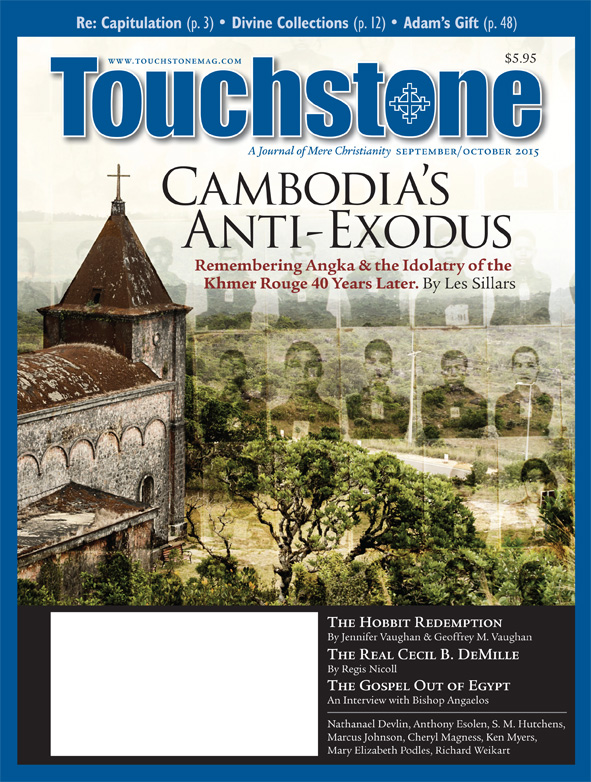

Cambodia's Anti-Exodus

Remembering Angka & the Idolatry of the Khmer Rouge 40 Years Later

This year marks the fortieth anniversary of the rise of the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. Led by Pol Pot, this Communist regime murdered about 1.7 million people between 1975 and 1979 in a doomed attempt to turn Cambodia into a Marxist agrarian utopia. Applying the principles of Mao with the speed and violence of Stalin, the Khmer Rouge executed hundreds of thousands of citizens by cutting throats and crushing skulls with hoe-handles. Most of the rest died of starvation, overwork, and disease.

No other regime in modern history has exterminated nearly a quarter of its own people, but it isn't just the violence that sets apart "Angka," the name of the revolutionary organization; no other government has ever attempted such totalitarian control over its citizens.

To do this, it turned socialism into a national religion, enforced with the legalism of the Pharisees and pretensions to the omniscience of Big Brother. Angka assumed control of family life and abolished all other institutions of Cambodian society, starting with Buddhism and all other religions. "Every citizen of Kampuchea (as the regime called Cambodia) has the right to worship according to any religion and the right not to worship according to any religion. Reactionary religions which are detrimental to Democratic Kampuchea and Kampuchean people are absolutely forbidden," declared the Khmer Rouge constitution in a gorgeous bit of Orwellian doublethink.

Angka also put an end to schools, private property, free markets, business, legitimate government, voluntary associations, private transportation, and anything that felt foreign. All that remained was the collective, embodied in Angka.

What's striking is how so much Khmer Rouge ideology resembled key elements of Christianity turned inside out and upside down. This was not deliberate, for the Khmer Rouge knew little of the Bible; Pol Pot insisted that everything about the revolution was Khmer in origin. Yet everywhere in Cambodia there were echoes of biblical truths that had been hideously distorted in the effort to create the "new socialist man." It's as if some alien intelligence, intending to create the most un-Christian society possible, distilled sixty years of applied totalitarianism from around the world into one ghastly system and then unleashed it on a small, unsuspecting country. Radha Manickam, a Christian, was one of the survivors.

Angka's Supremacy

I am the Lord your God. Manickam was 22 when the Khmer Rouge rolled into Phnom Penh and the other Cambodian cities on April 17, 1975. It was the end of a vicious five-year civil war against the U.S.-backed Khmer Republic. In the name of Angka, the Communists began herding, on foot, every single city-dweller, some two million people, into the countryside at gunpoint. These city folk were the "New People," those who had become rich by oppressing virtuous country folk, the "Old People," who had supported the Khmer Rouge during the civil war.

New People who resisted were simply shot, and thousands more died of dehydration and dysentery in the 100-degree heat as they trudged down the major boulevards. The Khmer Rouge cut off communication with the outside world and turned the country into one big labor camp. They planned to grow and export enough rice to purchase modern machinery and weapons, turning Democratic Kampuchea into a model of pure socialism.

Manickam, a member of Cambodia's ethnic Indian minority, had become a Christian two years earlier at one of the many Phnom Penh Evangelical churches that sprang up during the civil war. After the evacuation, he and his family—parents, grandmother, and six younger siblings—found themselves living in a village of tarp-tents in a field south of Phnom Penh.

A few months later, in June 1975, the Manickams were among the hundreds of thousands of New People shipped up to northwest Cambodia to dig dikes and canals and grow rice by hand. They arrived by train, where 14-year-old soldiers brandishing AK-47s pushed them out of the cars. An officer told them they had three days to build huts on a forested mountainside. After that, they would start to work for Angka. No food until then.

Angka's Authority

You shall have no other gods before me. That first evening in the new village, a Khmer Rouge cadre banged on the steel rim of a car wheel to summon the village to the first of many nightly propaganda sessions. Manickam and the other New People gathered near a fire and sat down on the ground in rows of ten, as instructed. The officer stepped into the light of the fire, faced them, and delivered the word of Angka.

Angka had permitted them to help build the new society, he said. Everybody must work very hard and they must be patient. The Glorious Revolution is still new, so there might not be much food now, but one day the principles of socialism will be fully applied to society. On that day they will have all the rice and fish and fruit they can eat, and more! In fact, one day there will be no more spoons! Angka will build machines that will feed you, so we won't even need spoons to feed ourselves!

Manickam stifled a chuckle at the thought of a feeding machine bashing out a few of this officer's teeth because he hadn't opened his mouth quite wide enough. A Communist utopia? Maybe ignorant peasants would swallow this nonsense, but why did they think educated people would buy it? It was infuriating. It was insulting.

The officer continued: For now, they must bear with Angka during this temporary shortage, which was caused by the capitalist oppressors, who have destroyed the country. It will take time to rebuild, but our brave soldiers of the Revolution have already driven out the Americans! (Nixon had authorized secret B-52 carpet-bombing campaigns of Cambodia during the Vietnam War.) This proves that nothing can hold back the Khmer people!

In the meantime, if they worked hard, they would be fed. They must learn from the Old People how to grow rice and build their own homes. The officer then delivered Angka's rules for the New People's cooperative. They had a depressing similarity:

• There is no private property. Everything belongs to Angka. If you are caught stealing from Angka, you will be crushed. ("Crushed" doesn't quite do justice to the Khmer word kamtech; it means to destroy completely and then wipe away any trace; to reduce to dust.)

• You must not lie to Angka. If you lie to Angka, you will be crushed.

• If you will not work, if you are lazy and live off the work of others, you have betrayed Angka. You will be crushed.

• If you try to fake illness to avoid going to work and are caught, you will be re-educated. Or crushed.

• Angka will provide for all your needs, including all your food. If you try to gather your own food apart from what Angka gives you, you will be crushed because you are betraying the trust of the cooperative.

The list was punctuated by warnings not to do anything stupid because "Angka has eyes like a pineapple and cannot make mistakes," a common Khmer Rouge aphorism.

Angka's Exhortation

Do not conform to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Now, continued the officer, we are free! We are all free, and we are all equal! You are free from General Lon Nol and his corrupt regime, free from the possessions that once enslaved you! Free from your cars and fancy clothes and gold and books. Free from your worthless schooling, free from all the corruption and oppression of a capitalist society. We do not need the things you used to have, your schools and churches and businesses. Do not think of such things, or you will not be able to work hard. Only the enemy needs or wants such things. We are all the same now. We all work for Angka, for the community, for the Revolution. You are happy here.

Manickam understood clearly that, happy or not, he had better not complain or mention fancy foods or comfy beds or anything about life before the Khmer Rouge takeover. The officer continued: We must struggle to reorganize society along Revolutionary lines. Correct revolutionary understanding will allow all good comrades of the Revolution to work to their utmost.

The indoctrination sessions took place most evenings for the next three and a half years. They lasted for hours, usually until after 10:00 or 11:00 p.m., and the main ideas were always the same, an endless recycling of rhetoric.

Angka's Confessional Demands

If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive us our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness. Later on during the regime, the meetings sometimes included sessions of "self-criticism," in which comrades were invited to admit to failures of devotion to Angka. Confessing something could earn one punishment, such as a beating or loss of meals. But not confessing something that Angka had discovered from its network of informers and child spies might lead to something worse, such as death in one of the 167 prisons spread throughout Cambodia.

Manickam met someone who survived a Khmer Rouge prison, a man named Sân. The cadres had hauled him off to a former Buddhist temple where he was whipped with electrical cords and saw much worse: cages full of scorpions and spiders, guards pulling out prisoners' fingernails with pliers, and horrible beatings. Memoirs by Khmer Rouge survivors in other prisons describe victims being tied to red ant hills and babies being slashed out of their pregnant mothers' wombs.

In Sân's case, the guards demanded that he confess to having been an officer in the Khmer Republic's army, but he hadn't been one and refused to say otherwise. He had made bicycles for Angka in Phnom Penh, he insisted, serving Angka loyally. After a month they let him go, making him one of the few to leave prison with his life. When he returned to the village, he showed Manickam the scars on his back.

Angka's Purges

You shall know the truth, and the truth shall set you free. Perhaps the guards had believed Sân, although that wasn't normally relevant to Khmer Rouge interrogators. They wanted confessions. The most terrifying of all Khmer Rouge prisons was Tuol Sleng ("Hill of Poisonous Trees"). Over 15,000 men, women, and children passed through the halls of the converted Phnom Penh high school, a three-story complex code-named Security Prison 21. Kaing Guek Eav, known as "Comrade Duch" (pronounced "Doik"), was in charge. He fit the stereotype of the faceless, soulless bureaucrat who supervised incredible evil without batting an eye.

While guards worked over a screaming prisoner manacled to a bed frame, an official sat at a desk and scribbled out the prisoner's "autobiography," beginning with his or her childhood. Most of the prisoners were loyal Party members, but that didn't save them from being caught up in the purges a delusional Pol Pot sent raging through the ranks beginning in 1977. Even he had seen that the country was disintegrating: starvation and disease were rampant, and rebellions flared up among some troops. But for Pol Pot, Angka and the Party line were infallible, so he deduced that spies and traitors must be responsible for the afflictions. In 1975 Tuol Sleng handled only a few hundred prisoners, mostly New People. By 1978 the place usually held over a thousand Khmer Rouge officials and their families at one time.

In futile attempts to placate their tormentors, prisoners eagerly confessed that they had spied for the CIA, the KGB, and the Vietnamese. Each prisoner fingered dozens of acquaintances, friends, and family members, who were themselves then rounded up and "interrogated." This "network investigation" confirmed the existence of ever-widening circles of counter-revolutionaries and justified Pol Pot's paranoia.

Those who survived the torture were trucked to a site outside Phnom Penh called Choeung Ek, a place now known as the Killing Fields. There they were slaughtered and dumped into mass graves. Duch, in a macabre -pretension to legitimacy, kept detailed files on all the prisoners, including confessions and photos of the brutalized prisoners.

There were only twelve known survivors of Tuol Sleng.

Angka's Bidding

Nothing in all creation is hidden from God's sight. Everything is uncovered and laid bare before the eyes of him to whom we must give account. All through that first meeting in 1975, as the sun went down and the air cooled, Radha Manickam sat peering at the speaker in the firelight, trying to swat inconspicuously at the mosquitos that swarmed out of the forest and attacked any exposed bit of skin. The more his limbs hurt, the more incredulous he became.

The group sat and listened, trying to look attentive. Revolutionary freedom seemed unlikely to include the liberty to whine about long meetings or mosquitos. When the session was over, the officer shouted "Long live the Revolution!" three times, and they echoed it back to him, saluting in unison with their raised fists. Then, "We are committed to obeying!" Then, "Long live Angka!"

Then they all headed to their makeshift beds under the trees, because they hadn't finished their huts yet.

Manickam spent the next several months assigned to work crews digging canals and dikes by hand, and most of the next three years on plowing crews. He ate in collective dining halls and slept in communal huts. He contracted malaria. He witnessed cadres cut the liver out of a living, screaming prisoner, then cook and eat it as the man died. His father and five of his seven siblings died of starvation or disease, and one was beaten to death at about age 9. By 1977 he weighed about 90 pounds.

Angka's End

Yet he survived, and although he was often furious with God, Manickam never turned his back on him. In 1978 he found new hope: cadres forced him to participate in a mass marriage, but his wife turned out to be the daughter of a Phnom Penh pastor and one of the several hundred Christians alive in Cambodia at the time. Together he and Samen held on through the remaining months of the regime.

That ended in early 1979, when, after Pol Pot's repeated provocations, the Vietnamese rolled through Cambodia and set up a puppet government. The Khmer Rouge retreated to the forests, where they fought and lost a ten-year civil war.

Manickam and Samen escaped to refugee camps in Thailand on January 1, 1980, and from there they emigrated to the U.S. They eventually settled in Seattle, where they raised five children. Manickam's one remaining brother and his mother also survived and have become believers. Today, Manickam runs a small ministry to Khmer churches in the Pacific Northwest and in Cambodia, which is still suffering the aftereffects of the Khmer Rouge regime.

Pol Pot died in the Cambodian jungles in 1998.

Angka's Meaning

Some Western socialists, trying to distance Communism from the Cambodian bloodbath, conceded that Pol Pot's methods went overboard but argued that overall he was heading in the right direction. This reduces the Khmer Rouge to a group of well-intentioned homicidal maniacs, thereby illustrating Raymond Aron's observation that Marxism is the opium of intellectuals.

The Cambodian genocide shows instead that even evil works within the bounds of human nature. Like many today, Pol Pot thought that people were blank slates, and he intended to create from them the "new socialist man." But orthodox Christianity teaches that human nature is not "infinitely malleable," to use Big Brother's memorable phrase. Therefore, to be most effective, evil must distort and warp what is good and true; it must have a starting point. Pol Pot would have been insulted by the suggestion that Angka was just a funhouse mirror-image of the Church, but that's how the dark powers in this world operate.

He probably understands that now. •

Les Sillars teaches journalism at Patrick Henry College and is on staff at WORLD magazine; his first book, Intended for Evil: A Survivor's Story of Love, Faith, and Courage in the Cambodian Killing Fields, was released by Baker in 2016.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on communism from the online archives

19.10—December 2006

Workers of Another World United

A Personal Commemoration of Poland’s Solidarity 25 Years Later by John Harmon McElroy

more from the online archives

35.4—Jul/Aug 2022

The Death Rattle of a Tradition

Contemporary Catholic Thinking on the Question of War by Andrew Latham

27.6—Nov/Dec 2014

Tales of Forbidden Stereotypes

Real-Life Men & Women & the Tragic Loss of Human Comedy by Anthony Esolen

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor