Column: A Thousand Words

Crucifix

by José Aragón

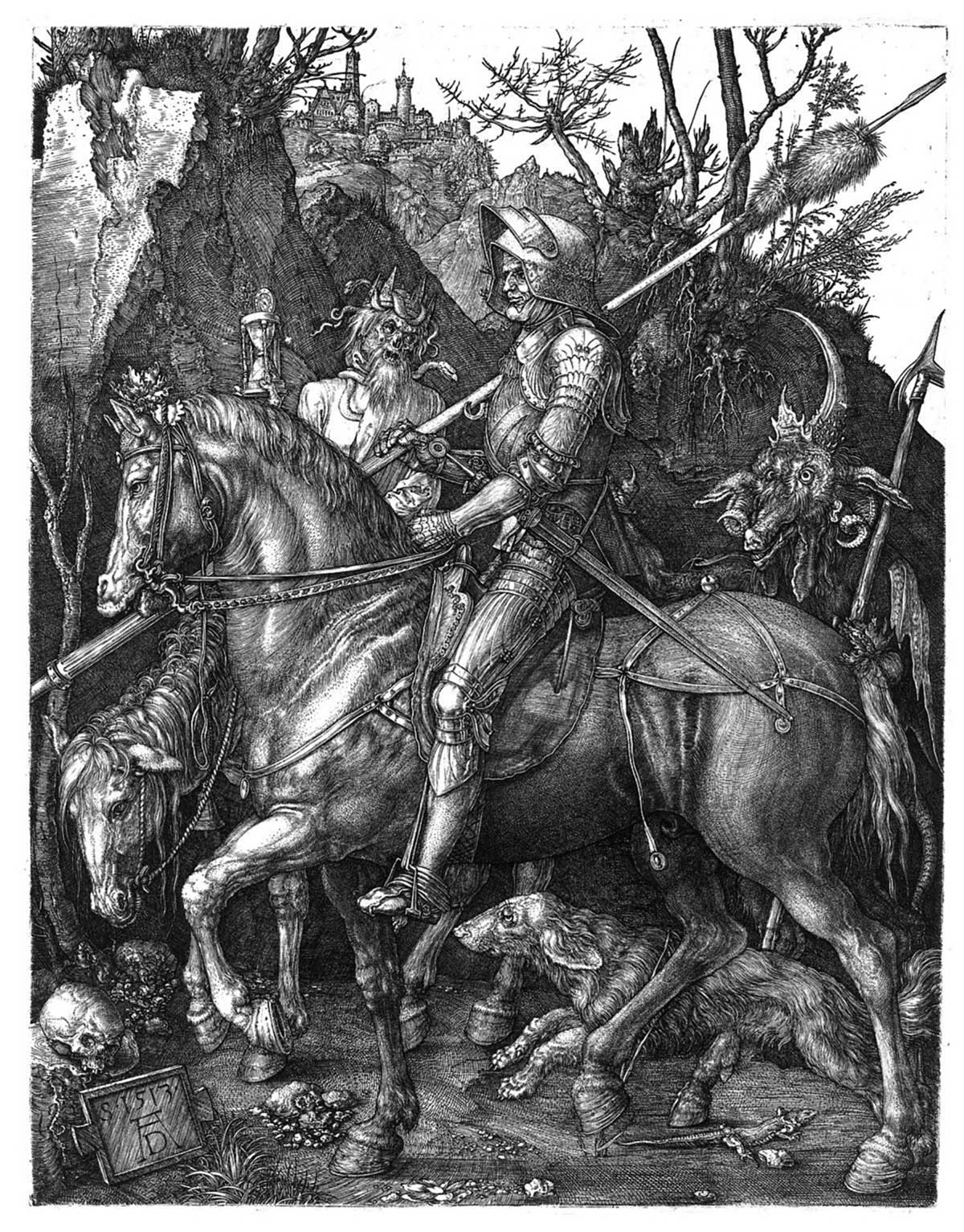

Unsigned and virtually unknown, this crucifix hangs on the wall of the tiny church of La Santisima Trinidad (The Most Holy Trinity) in the tiny town of Arroyo Seco, outside the slightly larger town of Taos, New Mexico. Yet it has a big history, a history that ties in with the remarkable history of faith in a very remote place. The crucifix is nearly life-size and hangs high on the wall so that the viewer can look directly at the face of Christ. Its style is rather abstract, a style often dismissively called "primitive" or "folk art."

In the nineteenth century, the painters and sculptors of sacred art in the Southwest, the "santeros" or saint-makers, moved away from the ornate naturalism of the Spanish Colonial Baroque style in favor of a sparer, pared-down style. One of the polarities we observe in the history of art is the pendulum swing between the naturalistic and the abstract, between the complex and ornate and the simple and stripped down. Here, then, are none of the glass eyes and jeweled teardrops of the Baroque, just the forms essential to convey the nobility and sadness of the suffering Christ, a simplicity appropriate to a country church out in the spare landscape of the New Mexican desert.

But if it is abstract in the formal sense, this crucifix, attributed to José Aragón (active 1820–1835), is on the other hand extremely graphic in its depiction of Christ's wounds. Bleeding head, bruised cheeks, scraped shoulders, rope burns, skinned knees, and blood oozing from underneath his loincloth: what prompted such a close attention to the very physicality of the Passion? One clue may lie in the history of the church of the Holy Trinity. It was built by the Penitente brotherhood, more properly called La Fraternidad de los Hermanos de Nuestro Padre Jesus Nazareno (the Confraternity of the Brothers of Our Father Jesus the Nazarene). Heirs to the cofradias (confraternities) and the flagellant societies of medieval Spain, the New Mexican brotherhoods were societies of men deemed to be of outstanding character, who dedicated their lives to suffering penance and doing good works; in short, imitating Christ in their daily lives.

The Penitente Brotherhoods

Until 1821, what we know as New Mexico was an outlying region of New Spain. When Mexico declared its independence, New Mexico was at the furthest reach of the diocese of Durango, nearly a thousand miles away. Under the new regime, church authorities recalled the missionary orders, the Franciscans and Dominicans, from New Mexico, intending to replace them with secular priests. Unfortunately, there were not anywhere near as many diocesan priests able (or willing) to go.

With clergy in such short supply, laymen, specifically the Penitente brotherhoods, stepped in to fill their role. Community leaders already, and of sufficient strength of character to withstand the stern penances demanded of them, the Penitentes built churches, baptized children, witnessed marriages, buried the dead, managed the charitable distribution of goods, and generally maintained social order. The image of their example and practices entered into the conception of painting and sculpture throughout the region.

During Holy Week, for example, the Penitentes took literally the words of Scripture: "Take up your cross and follow me." They carried heavy wooden crosses in pilgrimage processions, submitted to scourging and, in some instances, to actual crucifixion and near suffocation. Horrified observers, artists among them, saw at first hand the awful sufferings their sins had brought about. Some Penitentes, in acknowledgement of the connection between the masculine and physical sacrifice, made the Holy Week pilgrimage with a piece of cactus in their pants (whence the bloody loincloth).

The Feet of Jesus

At the foot of this crucifix there are two small figures. Following the medieval hierarchy of scale, they are smaller because they are of lesser importance. Traditionally, these would be Mary the mother of Jesus and John the Evangelist, who Scripture tells us stood with Christ on Calvary. But this is not your traditional crucifix: they are a Mary and a John, just not the ones you expect. This Mary wears her hair long and uncovered, and therefore is Mary Magdalene; this John is not the youthful apostle John, but a mature and full-bearded John the Baptist. Why this departure from the customary figures?

One thing that links the two, so different in life, is a connection to the feet of Jesus. Mary washed his feet with her tears and dried them with her unbound hair; John declared himself unworthy to fasten the latchet of Jesus' sandal. Still, this seems obscure, unless you know the full story of the sculpture's past. According to parish lore, told to me by the current sacristan, the crucifix was laid on the floor as the church was being built, and the Penitente brothers would begin each day's work by kissing the feet of the Lord. The crucifix was thus a part of the church before it was even built.

Preserved in Mind

Here the story takes a darker turn. Just before the church was finished in 1834, the crucifix was stolen, and it vanished. Still, though, it lived on in the communal mind of the parish, and its description was lovingly handed down through the generations. Our sacristan had heard the story from his mother, who was caretaker of the church, and she had heard it from her mother, also the church's caretaker.

By my estimation, the theft would have happened some seventy years before the grandmother was born. And yet the description of the crucifix was so vivid and so well known that, when the heirs to a wealthy Denver art collector returned it to the church wrapped in a sheet, the caretaker knew it at once by the single hand that peeked out from the wrappings.

So it was returned, perhaps as a gesture of repentance, on the occasion of the church's restoration in the 1990s, and there it hangs today.

Recommended reading:

• Mary Elizabeth Podles and Leon J. Podles, "Saint-makers in the Desert," America, vol. 167, issue 14 (Nov. 7, 1992).

• Thomas J. Steele, S.J., Santos and Saints: The Religious Folk Art of Hispanic New Mexico (Santa Fe: Ancient City Press, 1994).

Mary Elizabeth Podles is the retired curator of Renaissance and Baroque art at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland. She is the author of A Thousand Words: Reflections on Art and Christianity (St. James Press, 2023). She and her husband Leon, a Touchstone senior editor, have six children and live in Baltimore, Maryland. She is a contributing editor for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on art from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor