God Save the Queen

A People of One Book: The Bible and the Victorians

by Timothy Larson

Oxford University Press, 2012

(336 pages, $35.00, paperback)

reviewed by Louis Markos

One of the things that struck me the first time I read Augustine's Confessions is how thoroughly saturated the book is with quotes from the Psalms. It's not that Augustine uses the quotes as proof texts, or even as examples to illustrate his points. The quotes are there because Augustine clearly had most of the Psalter stored in his memory, and the verses flowed naturally—perhaps even unconsciously—out of his head.

I was happy to learn from Timothy Larsen's A People of One Book: The Bible and the Victorians that such a propensity for seeing the world through a biblical lens persisted into nineteenth-century England. Many of the key thinkers and shapers of the Victorian era, Larsen argues, were deeply grounded in the stories, images, and themes of the Bible. Through careful reference to a prodigious amount of primary material—both published works and private correspondence and diaries—Larsen demonstrates that Victorian writers of every religious (and non-religious) persuasion consistently expressed their ideas, passions, and personal biographies through the words of Scripture.

In addition to steeping himself in the actual writings of his subjects, Larsen, McManis Professor of Christian Thought at Wheaton College, has read widely in the biographical and critical work of his fellow historians. Alas, what he discovered by comparing and contrasting the primary and secondary material makes an all-too-familiar story: many academic historians have downplayed, overlooked, or even obscured the centrality of the Bible not only to Evangelical writers, but also to Catholic, Anglo-Catholic, Quaker, liberal Protestant, Unitarian, agnostic, and atheist writers.

Pusey's Vision

In his opening chapter, Larsen explores the work of E. B. Pusey, one of the main architects of the Oxford Movement, which attempted to move the Church of England closer to the liturgical practices of the Catholic Church. As an English professor who specializes in the nineteenth century, I expected to encounter orthodox (Nicene) theology in Pusey's writings, but I did not expect to find them so deeply grounded in a literal, expository reading of the Bible. Pusey's sacramental vision did not exist alongside the Bible; it was firmly founded in and upon it.

Indeed, while he argued for a return to older liturgical practices, Pusey also devoted considerable time and energy to writing biblical commentaries, including one on the book of Daniel. In sharp contrast to the German higher critics, Pusey, working from his thorough knowledge of biblical languages and textual criticism, vigorously defended the traditional date of Daniel. Alas, his reward for boldly exposing the unscientific presuppositions of the higher critics (in particular, their a priori rejection of prophecy and miracles) was to be labeled an obscurantist.

Reason for Pause

Larsen follows his chapter on Pusey with a well-constructed portrait of the man most responsible for reviving the reputation and influence of Catholicism in nineteenth-century England: Cardinal Wiseman. Wiseman held just as high a view of Scripture as any Evangelical Baptist or Reformed Calvinist today. In fact, far from defending Catholic doctrine against biblicist critics, Wiseman went on the offensive and argued that only the Catholic Church was consistent in its reading of the Bible.

And that assertive stance, Larsen demonstrates, was not confined to Catholics. Most Victorian Unitarians were equally convinced that a close, literal reading of the revealed Scriptures supported their own theological views.

Though Larsen works hard to remain objective, and refrains from critiquing his non-Christian interlocutors from the point of view of orthodox Christianity, his chapter on Unitarianism should give Evangelicals (like myself) pause. Too often, the doctrine of sola scriptura has led unsuspecting Evangelicals to think that the Bible should stand alone, apart from all creeds, dogmas, and traditions. As Larsen demonstrates, this was exactly the stance taken by such Unitarians as Mary Carpenter, who argued that when the New Testament was read in isolation from the Nicene Creed, it demanded a rejection of the Trinity and the Incarnation.

Authoritative & Binding

I took a great deal away from People of the Book, but perhaps the insight that struck home most powerfully was how even the most anti-creedal Victorians nevertheless felt the need to proof-text the Bible as a way of backing up their beliefs and actions. For instance, although T. H. Huxley, known to history as Darwin's bulldog, coined the word "agnostic" and denied the inspiration of the Scriptures, he consistently depicted his personal struggles in biblical terms, referring to his enemies as Philistines or Amalekites and characterizing all systems he did not like (whether religious or secular) as idolatrous. In the same way, Annie Besant, though she self-identified as an atheist and did not consider the Bible to be the word of God, often supported her own beliefs and causes by quoting the words of Jesus.

Though Larsen's objective stance prevents him from extracting a "moral" from the rather strange position taken by non-Christians vis-à-vis the Bible, I would suggest that their position may provide evidence for something like a sensus divinus. True, Carpenter's, Huxley's, and Besant's heavy use of biblical proof-texting could simply reflect their cultural moment, but might it not also reflect something deeper and more perennial? After all, as Larsen shows, the three of them were just as likely to proof-text the Scriptures in their public writings as in their private letters and journals. May not their often-contorted attempts to appropriate or domesticate (rather than simply dismiss) the words of the Bible suggest that man, even in his fallen state, recognizes the authoritative and binding nature of Scripture?

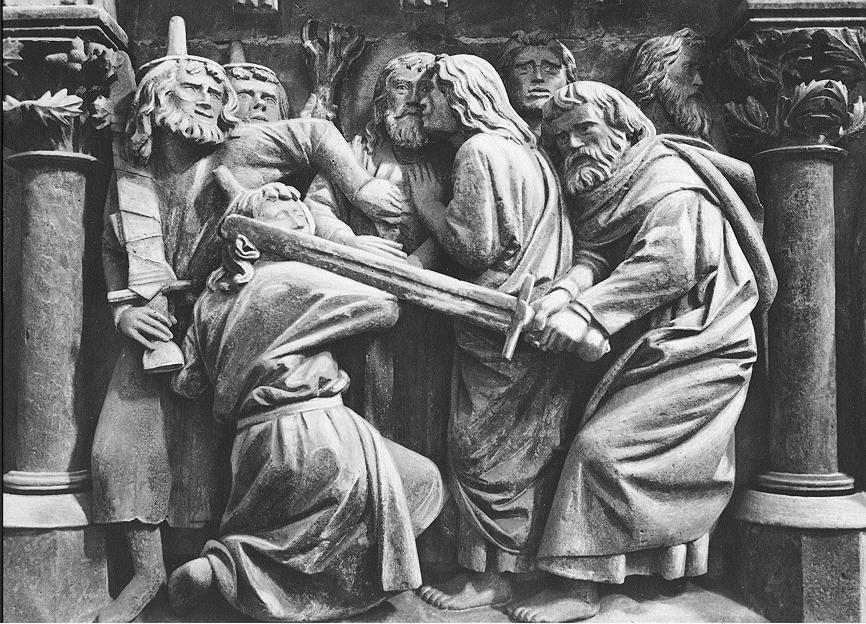

We are all, whether we admit it or not, aware of the demands of our conscience. That is why non-believers not only feel guilty when they violate the moral law implanted in their conscience, but also seek to justify their actions—often in religious terms. Just so, what Larsen uncovers in his study of Victorian biblicism may provide evidence that the Bible itself, even apart from the dogmas and institutions of the Church, is indeed "quick, and powerful, and sharper than any two-edged sword, piercing even to the dividing asunder of soul and spirit, and of the joints and marrow, and is a discerner of the thoughts and intents of the heart" (Heb. 4:12).

Louis Markos , Professor in English and Scholar in Residence at Houston Baptist University, holds the Robert H. Ray Chair in Humanities. His 19 books include Lewis Agonistes; Restoring Beauty: The Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the Writings of C. S. Lewis; On the Shoulders of Hobbits: The Road to Virtue with Tolkien and Lewis; and From A to Z to Narnia with C. S. Lewis.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on bible from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor