Feature

Kramer's Criteria

Hilton Kramer's Life of Cultural Discernment Meant Speaking Truth to Art

by Bradley W. Anderson

When the Russian writer and dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn at long last decided to allow his reclusive privacy in Vermont to be invaded by the New York Times for a 1980 interview, he did so under one condition: he would speak only to one man at the Times: Hilton Kramer, their chief art critic. It was an unusual request, since there were any number of literary or foreign-affairs experts who would have been more logical choices from the perspective of the Times. Solzhenitsyn was perhaps the most famous and unapologetic Russian Orthodox Christian in the world, and yet he chose, as the one man he trusted at the New York Times, a not particularly religious man.

What mattered was that Kramer's reputation for honesty had preceded him, making him someone Solzhenitsyn could depend on to tell the truth—something Solzhenitsyn, too, valued above all other qualities. Sealing the deal was perhaps Kramer's review of The Gulag Archipelago in the Times a couple of years prior. From that essay alone, Solzhenitsyn would have known that Kramer believed what was told in the Gulag—a story of systematic and decades-long terror in the Soviet Union going back to the earliest days of the Bolshevik revolution.

Perhaps just as importantly, Solzhenitsyn knew from Kramer's other writings on art and culture that he was no jingoistic booster of whatever America and the West happened to be up to at the moment. Kramer rather shared the Russian author's skeptical view of where Western culture was headed—deep into a world of nihilism, unbelief, and cultural decadence. While each was coming from a different vantage point—Solzhenitsyn from without, Kramer from within—both were observing the phenomenon and critiquing it with tools fashioned from the flotsam and jetsam of a disintegrating culture.

A Beachhead Established

Hilton Kramer died last year, and with his passing a great friend of what Russell Kirk liked to call "the permanent things" was lost. While he made his name at the New York Times, penning reviews and essays that chronicled the ebbs and flows of contemporary art and culture, his primary legacy is that he was the founder and long-time editor of the influential journal, The New Criterion. Among the broader public, most have probably not heard of that journal and even fewer have heard of Hilton Kramer, but his influence was both broad and deep, extending far beyond the small (about 6,500) circulation of his magazine. Such numbers pale beside those of better-known publications of cultural influence such as the New Yorker or Harpers, let alone major newspapers like the New York Times, but the impact of a periodical cannot be determined merely by circulation figures and advertising dollars.

What Kramer accomplished with the founding (in 1982) and eventual success of The New Criterion was nothing less than the establishment of a beachhead on the hostile coastline of a postmodernist nihilism that had by then firmly captured the fancy of the world of "high culture" in America. We see that nihilism in contemporary art of all kinds: novels and poetry, painting and sculpture, music and theater. Whether expressed with angry destructiveness or sardonic sneers, it is all part of the same Zeitgeist, and Kramer didn't like it. His story is a remarkable one that illustrates how one man, working with a small group of like-minded writers and thinkers, can have a profound impact on the broader cultural scene. At the risk of trivializing it with a common catchphrase, it is the story of how one man can make a difference.

The Journalistic Path

Kramer, a New Englander whose college education was at the well-respected but hardly "elite" Syracuse University, took a path that would be unusual today for a budding intellectual. In spite of being respected and feared as an arts critic by artists and academics alike throughout his career, he self-consciously chose a path as a journalist, proving that one does not need the imprimatur of a university post to engage in rigorous analysis of culture and the arts. As Roger Kimball, current editor of The New Criterion, noted in the lead essay of a special issue (May 2012) devoted to Kramer's memory, one of Kramer's favorite quotations was from Ernest Newman, a music critic for the London Times, who remarked that "journalist" was a term of contempt applied by writers who are not read to writers who are.

That quotation sheds light on Kramer's understanding that it is not enough to have good ideas and sound principles. Those ideas and principles must also be expressed in forums where they can engage other opinion-makers, and thus eventually the broader public. That process of engagement cannot take place solely in the ivory towers of the university or solely at the level of popular journalism; the discourse must simultaneously occur at various levels and in multiple forums. Sometimes cultural and artistic movements begin at the esoteric levels of academia or high culture and then percolate out into popular culture, ending up on television or in the pages of Reader's Digest; other times, changes take place in the opposite direction, beginning with movies or popular music, and ending up having doctoral dissertations devoted to them and college courses taught about them.

Smaller, serious journals of criticism and ideas play a critical role in the process of evaluating and making sense of the overwhelming load of ideas and artistic output of a vibrant culture, as do the arts pages of major newspapers and magazines. From this position in the middle, so to speak, a journal like The New Criterion can address trends in the academy and discuss the latest scholarly works on artistic and cultural issues, and, at the same time, critique trends of serious social and moral consequence emerging in the popular culture.

Room for One More

In 1982, many of Kramer's contemporaries were incredulous that he would step down from what was perhaps the most prestigious job one could have in his line of work—chief art critic for The New York Times—throwing it all over for the risky venture of starting a new periodical. It was an incomprehensible move from a career-development standpoint (Kramer was only 54 at the time), and even for those sympathetic to his cultural vision, voluntarily giving up the biggest bully pulpit in the country (America's unofficial "newspaper of record," with a circulation of over one million until very recently) was a major gamble.

Kramer had had the personal integrity not to pull any punches while writing for the Times, but his clear-eyed critiques often provoked conflicts with higher-ups who disagreed with his views, and his ambit was largely restricted to the visual arts. At the helm of his own publication, not only could he venture broadly across the entire spectrum of the American scene, but he could also provide a forum to a variety of critics—mostly younger ones who would otherwise have had little outlet for their talents—weaving the entirety into a comprehensive critique of American higher culture. In Kramer's opinion, such a critique was long overdue. In the introductory essay to the first issue of The New Criterion, he stated that the job of criticism was "to distinguish achievement from failure, to identify and uphold a standard of quality, and to speak plainly and vigorously about the problems that beset the life of the arts and the life of the mind in our society."

While acknowledging that there was no shortage at that time of journals and magazines devoted to culture and the arts, Kramer spoke plainly about why he was convinced there was room for one more—one that addressed an unmet need in the world of criticism and commentary:

[M]ost of what is written in these journals is either hopelessly ignorant, deliberately obscurantist, commercially compromised, or politically motivated. Especially where the fine arts and the disciplines of high culture are concerned, criticism at every level—from the daily newspaper review of a concert or a novel to the disquisitions of critics and scholars in learned journals—has almost everywhere degenerated into one or another form of ideology or publicity or some pernicious combination of the two.

Kramer was quite clear in his mind about just when the normal ebbs and flows of America's cultural life had taken a distinctly sharp turn for the worse, saying that "we are still living in the aftermath of the insidious assault on the mind that was one of the most repulsive features of the radical movement of the Sixties." While most individuals of traditional sensibilities are acutely aware of the assault on traditional morals that began in the 1960s and has continued to the present day, it is less common to think of it as an "assault on the mind." And yet it was and is so.

The Inexcusable Failure

Which brings us back, in a way, to the Solzhenitsyn anecdote that began this essay. For Kramer, the radical left in all of its forms—Marxism, Leninism, Stalinism, the progressive movement, and the radicalism of the 1960s and beyond—loomed over the twentieth century, and he wrote extensively about its effects. In his 1999 book, The Twilight of the Intellectuals: Culture and Politics in the Era of the Cold War, he wroteabout the progressive movement that was strongest between the 1920s and the early 1960s in America and that persistently slipped leftist thought into the mainstream, undermining traditional Judeo-Christian morality and the values of Western civilization. He specifically discussed the way in which these political and cultural commitments took on a religious fervor:

The progressivism I speak of was an ethos, a cast of mind, a secular faith that reached into every aspect of living and thinking. It was thus as much a code of feeling as it was a mode of thought. Its loyalties determined everything from literary taste and the choice of spouses to the way children were educated and political events responded to. At the height of its influence, progressivism had an answer—or at least a response—for every question. . . .

About a whole range of historic events and public figures . . . progressives adopted an iconography and a demonology that have remained impervious to critical doubt or documentary evidence down to the present day. Which is why there has been no discernible impact on what remains of the progressive mind by [revelations] emanating from the KGB archives in Russia.

One might fairly object that virtually any movement that involves a political element can take on, for some, a religious tenor. Kramer's deep critique of the political left, however, takes this into consideration. For him (who spent most of his life as a self-described liberal), what was most inexcusable was the failure of the left ever to come to terms with the enormity of what communism actually produced in the twentieth century, and its failure to condemn it in no uncertain terms.

Writing about Josephine Herbst, a once-prominent novelist who had made him (inexplicably, from his perspective) her literary executor, Kramer talked about learning from her papers how deeply committed she was, like so many American intellectuals of her time, to defending Stalinism. During the height of the countercultural revolution in American universities, he also learned, based on the steady stream of graduate students sent to him for access to her papers, the extent to which leftist professors were quietly going about the process of rehabilitating the image of Herbst and other Stalinist intellectuals of the 1930s and 1940s.

While not minimizing the fact that self-deception and lying are in part the result of things other than politics, Kramer wrote about her with a sense of compassion for the way a political ideology had brutalized her and other adherents of the Bolshevik "religion" no less than it brutalized those it oppressed:

It is in the nature of Stalinism for its adherents to make a certain kind of lying—and not only to others, but first of all to themselves—a fundamental part of their lives. It is always a mistake to assume that Stalinists do not know the truth about the political reality they espouse. If they don't know the truth (or all of it) one day, they know it the next, and it makes absolutely no difference to them politically. For their loyalty is to something other than the truth. And no historical enormity is so great, no personal humiliation or betrayal so extreme, no crime so heinous that it cannot be assimilated into the "ideals" that govern the true Stalinist mind, which is impervious alike to documentary evidence and moral discrimination.

An Aggressive Secular Faith

Which again brings Solzhenitsyn to mind. One of the criticisms of The Gulag Archipelago is its mind-numbing length, the seemingly endless details of the persecution of the Russian Orthodox Church, of intellectuals, of dissidents of every stripe, and of millions of bystanders who were innocent by any standard of judgment. Could all of this not have been more effectively conveyed in a few hundred pages?

The quotation above from Kramer shows why this level of detail was necessary. Solzhenitsyn knew that he was not dealing with a garden-variety repressive regime merely interested in power. He was exposing the reality of life under an aggressive secular faith, a faith with ardent and well-placed adherents and secularist sympathizers throughout Western countries, adherents whose faith not only allowed them to believe lies and to tell lies in the interest of promoting it, but also expected them to lie whenever told to do so, and, eventually, without any prompting whatsoever.

All of this might seem excessively political territory for an art critic. The reality, though, is that the times in which Kramer found himself writing were ones in which the boundaries between art and politics had been intentionally shattered. Intellectuals and artists of the twentieth century, cut off from the religious and cultural heritage of what was once simply referred to as Christendom, proved in their professed state of unbelief to be deeply susceptible to political religions that rivaled any merely spiritual "great awakening" in their ecstatic claims and their demands for complete surrender of the self. As Kramer later wrote, "the Cold War was always as much a war of ideas as it was a contest for military superiority."

Just as Solzhenitsyn chronicled the history of oppression in the Soviet Union in painful detail, knowing it was necessary, Kramer's writings recorded the history of the corresponding war of ideas as it took place in the art galleries, museums, and literary institutions of the West.

Witty & Innocent

As a critic, Kramer was willing to engage what had become a politicized art world, rife with ideology. When necessary, he would take on the ideology head-on, but what he much preferred to do was simply to talk, truthfully and honestly, about the art itself. At the center of his understanding of a critic's responsibilities (he treated his work as a vocation, not a career) is that there are standards by which good art can be distinguished from bad, or, to put it more gently, by which some works of art can be objectively deemed better than others.

He further believed that some ideas are healthy for a society and that others are pernicious. During his long immersion in the art world, he never turned a blind eye to the fact that certain works are promoted and others denigrated for reasons that have nothing to do with artistic merit. Whether in reference to an inferior painter who was the toast of New York because of the fashionable political views he held, an overrated photographer whose claptrap was the talk of the town because of its shock value, or a play that got good reviews because of the artist's social connections, Kramer was not afraid to shine the light in dark corners that others might pretend weren't there. Needless to say, while he was respected and feared, he was also often not liked, especially by those who knew he was onto their game.

One story told many times about him is worth repeating (Kramer himself was said to have remarked that anything worth saying is worth saying over and over again): Kramer found himself one evening at a fashionable dinner in New York beside filmmaker Woody Allen, a great favorite of most movie critics. Allen asked whether Kramer was ever embarrassed when he ran into artists in social situations after he had panned their work. Kramer's reply was, "No, why should I be embarrassed?" He went on to tell Allen that if anyone should be embarrassed, it should be the artist, who created the bad art in the first place. "I just describe it," Kramer said. Roger Kimball, writing after Kramer's death, noted that

Hilton's response was both witty and innocent—witty, because it was a riposte unanswerable, innocent because it was only on his way home from the event that Hilton remembered he had written a negative review of The Front, a piece of left-wing agitprop about the Hollywood blacklist, in which Woody Allen acted.

The story is an amusing one, but more than that, it puts flesh on a characteristic of Kramer's that many commented on after his death: his commitment to honesty. One might hope that those who would presume to critically analyze art and the culture that produces it would of course be honest—but one might also hope for too much.

The world of the arts and of criticism at its highest levels is a rather small one, and the currencies of mutual back-scratching are the usual ones—the critics who say the nice things are the ones who get invited to the smart social functions; your brilliant intern gets an entry-level editorial job at the other guy's magazine (but perhaps not if you just published an essay demolishing the premise of his recent front-cover article); you are, on the strength of your deft ability to write witty but ultimately harmless pieces, invited to write major essays for "important" and well-paying magazines. That sort of thing. One suspects that Kramer was not on Woody Allen's short list when the latter gave his own dinner parties. One is equally certain that it didn't influence Kramer one way or the other.

Emulating Eliot

Kramer and his editorial partner, the pianist and music critic Samuel Lipman, who became the publisher of The New Criterion, indicated the level of influence they were striving for when they chose the name of their magazine. They were signaling that they intended (taking into consideration differences in cultural milieu, individual talents, and the tasks at hand) to emulate the great T. S. Eliot and his Criterion, which was published in London during the 1920s and 1930s. While short-lived and of miniscule circulation (900 copies at its peak), that publication was nonetheless one of the most influential literary journals of the twentieth century, edited by a man who was perhaps that century's greatest literary genius, so they were choosing to set the bar high.

There are differences between The Criterion and The New Criterion, to be sure. Most prominent among them is the much broader scope of the latter. Eliot's magazine was focused on literature, while Kramer's took a much broader view, covering dance, theater, music, the visual arts, the media, fiction, and non-fiction. In addition, The New Criterion, recognizing that any barrier between art and politics had been smashed and splintered into irrelevance by the leftist countercultural revolution of the 1960s, consciously and unapologetically addressed political issues and fads, especially with respect to their effect on our cultural institutions and their influence on the content and style of artistic endeavors.

One striking point of similarity between Eliot and Kramer is the consistency of their critical vision, or, to borrow the term Kimball uses in the essay mentioned above, their "critical temper." In the New York Times review of Kramer's book, The Triumph of Modernism,

a reviewer lamented:

The book does not offer a restatement of any of Kramer's critical positions, still less an elaboration of them. There are no modifications, no second thoughts, no justifications. Kramer has resisted the temptation to rewrite these pieces. . . . Kramer, it appears, continues to think exactly as he did 20 years ago. This is perhaps a pity. Second thoughts are often more interesting than first ones, and current opinions more interesting than historical ones.

It is indeed true that there is a remarkable consistency to Kramer's work through the years, but the same can be said of Eliot and other great critics of the past. Some of the consistency reflects their unchanging opinions about fundamental truths, but even more of it comes from an internal attitude of honesty in appraising artistic works and cultural phenomena. In the various essays written in tribute to Kramer after his death, there were many stories about his almost guileless approach to the art and artists he wrote about.

Even more striking, in some ways, were the stories of Kramer, as editor, giving free rein to bright young writers and standing by them when they drew withering criticism for having boldly (and sometimes recklessly) slain sacred cows or at least stepped on their hooves. This he did even when he didn't personally agree with their conclusions and when backing them up involved an element of personal cost. Not only did Kramer intend to be honest himself, but he also wanted the writers he was nurturing to be honest—to learn to be true to their critical instincts, their artistic impressions, their sense of morality, and their reasoning abilities.

Leading by example, Kramer helped teach a generation of critics that it is not enough just to know what one likes. One must be able to articulate, reasonably and without resorting to cant, snideness, or jargon, why one work of art is better than another, and why one is worthy of praise while another is worthy only of dismissal or even condemnation. Along with his honesty, one of Kramer's great contributions to "the permanent things" was, again, this unapologetic insistence on discerning between good and bad, beautiful and ugly, and right and wrong—and his equally unapologetic determination to pass these curious and antiquated notions on to those he mentored.

Embracing Artistic Modernism

Appeals to the realities of "modern life" have been used to justify countless obscenities, desecrations, and transgressions against basic humanity, let alone against traditional morals, religion, and mores. It might, then, come as a surprise that Kramer was not an artistic antiquarian, immersed only in masterworks of a glorious past. Rather, he embraced artistic modernism, seeking to engage and describe the art being made in his own lifetime, created in response to the world he was living in. He was a champion of abstract expressionism in the visual arts because of its ability to rise above the chaotic content of modern life; he liked the simple honesty of the most insightful modernist architecture; and he admired the stark incisiveness of literary modernism at its best.

These sensibilities were not always shared by those who otherwise agreed with his negative assessment of the direction in which Western culture was heading. It was, in fact, one of Kramer's achievements that he was able to help a generation of readers see modern art through new eyes—not as a degenerate revolution against traditional standards of truth and beauty (although there was plenty of that, too), but rather as a movement that, at its best, responded faithfully, as much as the given realities of modern life allowed, to the intellectual and social changes of the last century.

In the essay "Modernism and Its Institutions," collected in Lengthened Shadows: America and Its Institutions in the Twenty-first Century, Kramer said of T. S. Eliot, himself the father of a clear-headed strain of modernism in literature, that "Eliot's effort was not to subvert tradition but, on the contrary, to salvage it from the sclerotic imperatives of an exhausted antiquarianism or impotent gentility."

The combination of being an artistic modernist and a cultural and political traditionalist made perfect sense to Kramer, for whom the two were organically woven together in his critical life. Those who may at first have been skeptical (present company included), but who read The New Criterion through the years, came to understand modernism in a new light, seeing its many currents, learning to separate the pretentious from the profound, and the trendy from the potentially timeless.

Most importantly, readers discovered that while engagement with a canon of proven artistic worth—from Shakespeare to Rembrandt to Chopin—is an irreplaceable anchor, life without contemporary artistic engagement with the human condition is an impoverished one, even if the alternative involves sifting through the dusty sands of trendy postmodernism to find the occasional jewel that makes it all worthwhile.

The Perverted Amalgam of Postmodernism

Any age has its darkness, and the age of modernism was decidedly not an exception. Kramer pointed out that even Eliot had "illustrated the apparently unavoidable paradox that the advent of modernism brought with it the seeds of its own perpetual renovation." This "perpetual renovation" had the potential for decadence as surely as it had the promise of fresh insights into the particularities of modern life, and no one knew this better than Kramer. Much of his life as a critic was spent exposing the humbuggery and snake oil that is often gathered under the label of "postmodernism" (or of "modernism" for that matter).

Like any heresy, postmodernism was not so much a new movement (although many a charlatan wanted to claim it to be so) as it was a perverted amalgam of old ones. There had always been streams of modernism that were assaults on the life of the mind and spirit (such as Dadaism), but the latter half of the twentieth century saw those trickles turn into veritable floods. Apart from the objectionable moral content of postmodernism (of which there was plenty, to be sure), Kramer wrote that

The problem with postmodernism is not that it embraces architectural ornamentation or representational painting or self-referential plot lines. The problem is postmodernism's sentimental rejection of the realities of modern life for the sake of an ideologically informed fantasy world. In this sense, modernism is not only still vital: it remains the only really vital tradition for the arts.

There one has it: the nexus between dangerous and vicious "ideologically informed fantasy worlds" (such as communism) and perverted strains of art created by those whose "loyalty is to something other than the truth." Those strains serve not to remind man of the higher things to which he is called, but rather to enslave him to the passions, which plague him quite enough without any assistance.

Reconstructing Wastelands

Most of us have known only a steady disintegration of Western culture during our lifetimes. In America, our heritage can be understood properly only in relation to the historical reality of Christendom—both in the ways our country has embraced it from the beginning and in the ways it has rejected it from the beginning (and continues to reject even more parts of that heritage with every passing year). It is not irrational to wish to withdraw from a disintegrating culture, but that impulse has a way of containing the seeds of its own fulfillment.

T. S. Eliot saw the rot and hollowness, but kept working, creating monumental art and crafting essays about literature, ancient and modern, that spoke to the intellectual and spiritual needs of his time. Solzhenitsyn did the same thing, and furthermore once wrote that an artist has to engage life as he finds it, not as he wishes it to be. Both men brought their considerable intellectual resources to bear on the task of reconstructing wastelands.

Hilton Kramer is no longer with us, and many of the things he wrote about are now in the history books, for better or for worse. But The New Criterion, the journal he founded and nurtured to adulthood, is still here. Those who would themselves seek to engage and understand more deeply the milieu in which we find ourselves today—cultural, artistic, religious, and moral—could hardly do better than to add its pages to their reading, continuing the conversation.

Discernible Art

by S. M. Hutchens

I am skeptical, because of the actual history of the phenomenon, about the ability of the intentional modernism of any age to achieve what Kramer was looking for—a quality that draws it, considered as a whole, into the Great Tradition. I also believe, however, that beauty may be found in what from our perspective is new because it is a transcendental quality whose root cannot be grasped. It is given by God as a pure grace, even in places where wickedness abounds, and while it is found in abundance where he is loved and honored, still, it is by its very nature beyond the reach of both the artist, whatever his intention, and the critic, whatever his criterion.

On a practical level, however, I associate artistic modernism with those who are vainly attempting evolution through destruction or abandonment of a grace that has gone before, who think that for something new to begin, something old, thus inferior, along with its sensibilities, has to be killed, because in general, that is what they do. I also believe in golden ages that are replaced by lesser ones and never come again, that the movement from Mozart to Cage or from Caravaggio to Lichtenstein is a descent from greatness to mockery by those who, lacking its spirit, hopelessly covet what they do not have, and will not find their own worth in submission to the greater.

I believe artistic modernism survives by gulling the insecure with its pretensions, but that from time to time beauty and meaning can be found in its degraded media, just as a violin can be made of trash, and an urchin possessed by the spirit of God can arise from his barrio to play it. But when he does, he will play Mozart, not Cage.

A Monitory Finger

The resistance of the human spirit to modernism is clearly discernible in the custom of never placing the modernistic orchestral piece last in the program. The cognoscenti, trying to educate their inferiors to its value, know perfectly well what would happen if they put it at the end. The hall would empty as the rubes and philistines, repelled by its ugliness, streamed toward the parking garage. As the customary arrangement goes, however, the unenlightened must be pelted by the dreck if they want to hear Don Juan or Swan Lake. At last Saturday's (as I write) symphony concert, we had to sit through the grunts, wheezes, whines, whops, and shrieks of the guest conductor's "brilliant" invention to win through to Stravinsky's Firebird.

Which, of course, brings back the question of grace and its actions within any modernism. Surely Stravinsky was, like Beethoven, in some real sense a modernist who, while building on tradition (that is important), in other ways thumbed his rather considerable nose at it. But today much of his modernism holds an undisputed place in music's Great Tradition. This realization raises a monitory finger to those who (like me) are inclined to pre-chuck the whole modernist business.

That is where a judicious critic like Kramer strikes a chord, for even though in general I am not patient enough to sift the manure to find the occasional gold, I will, because of this conception of grace, allow that a delicate flower may even be found in Mordor. More than that—I believe the disciplined liberality of mind necessary to recognize such a flower should be rigorously maintained among those who abjure Sauron and all his works, for to know the Lord is to recognize him in whatever unlikely place he

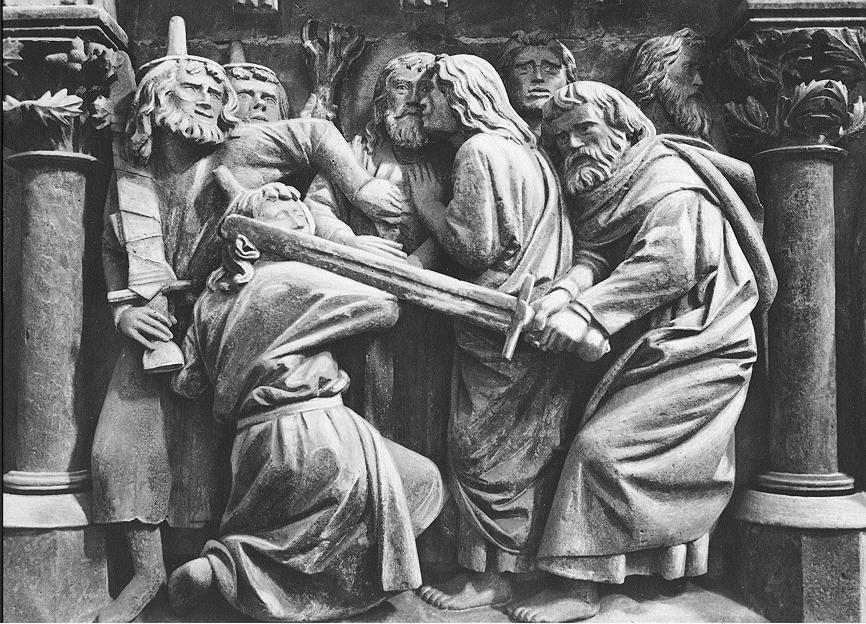

may go.Eloquent Ugliness

The first work of graphic art that forced me many years ago to think hard on the subject was the head of Rouault's suffering Christ. This spoke more eloquently of the "man of sorrows" than anything I had yet seen, perhaps because the horror of ugliness was necessary to speak of the suffering of the Lord, and in this case the brokenness of a modernistic form could supply what was above all necessary for the depiction of the brokenness pro nobis of the Savior, something the more classical icons of the Crucifixion never seemed to get quite right.

It strikes me, however, that in more pious times one may have had to go through a great deal of the serious but uninspired before he happened upon artistic beauty (this is well depicted in Shaffer's Amadeus), but he did not have to subject himself to the ceaseless, insulting effrontery and the endless filth and blasphemy of our time's intentionally "modern" to find it. That is why I am willing to recognize the power of the Resurrection when I come upon it in what is called "modern art," but do not make a practice of seeking the living among the dead. •

Bradley W. Anderson writes from South Lake Tahoe, California. His feature article, "Kramer's Criteria," was the cover piece for the July/August 2013 issue of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on biographical from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor