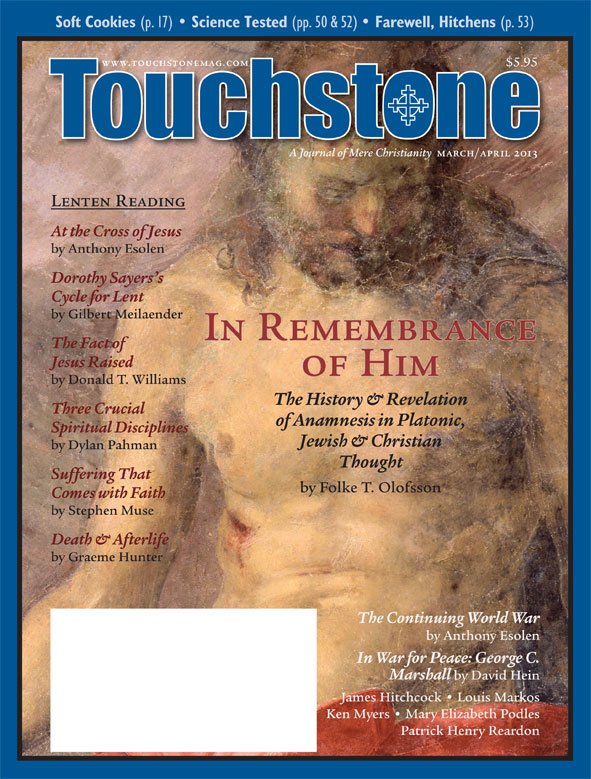

All This in Remembrance

The History & Revelation of Anamnesis in Platonic, Jewish & Christian Thought

by Folke T. Olofsson

Both Luke and Paul use anamnesis ("in remembrance") in their accounts of the Last Supper. The English translation does not do this rich word justice.

The ancient Greeks were quite familiar with and used this word. In one of Plato's dialogues, Meno, he lets his mouthpiece, Socrates, present the theory of anamnesis as a response to what has become known as the sophistic paradox, or the paradox of knowledge. Meno poses the question of how knowledge can be gained at all:

How will you look for something when you don't in the least know what it is? How on earth are you going to set up something you do not know as the object of your search? To put it in another way, even if you came right up against it, how will you know that what you have found is the thing you didn't know? (Meno, 80D, from Edith Hamilton and Huntingdon Cairns, eds., Collected Dialogues of Plato [CDP], trans. W. K. C. Guthrie [Princeton Univ. Press, 1961], p. 363.)

Since sure knowledge, then, seems to be impossible, is the search for knowledge futile? Socrates answers objections like these by referring to anamnesis, the idea of recollection. The human soul, he says, "since it is immortal and has been born many times, and has seen all things both here and in the other world, has learned everything that is. So we need not be surprised if it can recall the knowledge of virtue or anything else which, as we see, it once possessed" (Meno, 81C, CDP). What we call "learning something" is essentially a recollection of what the soul already knows, and the teacher is more like a midwife. Why have we forgotten? The trauma of birth makes the soul forget what is known, but it is all there within us: anamnesis.

In the dialogue Phaedo, Plato further develops his theory of recollection and combines it with his idea of forms. The soul is preexistent, eternal, and immortal; through anamnesis man can gain knowledge. The way through anamnesis to knowledge is by disregarding the body and purifying oneself from the bodily senses. It is through this purification—katharsis—and through philosophical thinking (one is tempted to say, "pure reason") that man obtains knowledge.

But why is the soul immortal and what kind of knowledge does it obtain? The answer is that "the soul is immortal because it can perceive, have a share in truth, goodness, [and] beauty, which are eternal" (Introduction to Phaedo, CDP, p. 40). Through this participation, in which the soul has its identity, the knowledge it gains is a knowledge of the Absolute. In other words, "man can know God because he has in him something akin to the eternal which cannot die."

This knowledge or even participation in the Absolute does not, however, include man's total existence, since it excludes his body. It is a purely intellectual, spiritual thing, the immortality of the soul. Plato's view is, therefore, ahistorical. It is not concerned with what is going on in the "real world"—with things, physical connections, and historical events—because the "real world" is not the real world. The real world is the world of Forms, of the Absolutes.

The Jewish View

Zikkaron is the Hebrew word for the Greek anamnesis. The difference between the two conceptions can hardly be exaggerated: they represent two different worlds, two different modes of understanding human existence.

The Hebrew word is "a sacrificial term that brings the offerer into remembrance before God, or brings God into favorable remembrance with the offerer" (International Standard Bible Encyclopedia). It refers to something given in time and space, which is the point of reference and contact between man and the Absolute, between man and God—in this case, man's action in the form of a sacrifice, offered in the context of liturgical celebration. This commemoration of something that has happened in space and time becomes clearly visible in the celebration of Passover. It is a memorial set up to be observed as a liturgical remembrance of sacred history.

At the celebration of Pascha, the youngest participant asks why this night is different from all other nights (Ma Nishtana), and, in an elaborate liturgy, the Exodus from Egypt is not only remembered and commemorated, but is re-actualized, re-presented through the retelling of the Exodus story (Maggid). Those present are not only remembering something in the past, as if they were witnessing the event from afar, but are participating in the actual Exodus through the liturgy. Their celebration is a part of God's ongoing saving activity, not only in the past, but here and now, concluding with the expression of hope that the Messiah will come and that the next celebration of Passover will be in Jerusalem, the Holy City. In the present, the celebration looks back to something that once occurred, and it looks forward in hope to something that will happen in the future, and all is encompassed in God's mighty and liberating deeds for his people.

We can say that the reason for the celebration of Pascha is man's reaction to God's action. It is not an end in itself, a nice tradition to strengthen the Jewish identity, although that may come as a byproduct. It is God's initiative, his action, which is "the reason for the season." The zikkaron of Pascha points towards two other fundamentals in the Jewish faith: the Covenant and the Confession.

At Mount Sinai, God made a covenant, sealed in blood, with the people of Israel, by giving the Ten Words, the Law. It is very important to notice how the covenantal text is introduced. It does not start with "thou shalt not," that is, with man's obligations. Rather, it begins with what God has already done: "I am the Lord, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage" (Ex. 20:2). Then follow all the thou-shalt-nots, starting with the First Word, "Thou shalt have no other gods before me."

Also, in the Jewish confession of faith, the Shema, the final paragraph contains an exhortation to remember God's commandments and to be holy to him, ending with the words, "I am the Lord your God, which brought you out of the land of Egypt, to be your God: I am your God" (Num. 15:41). The ground and reason for the confession of One God is God's own saving action, the salvation history that the confessing person, in recalling, makes present, is drawn into, and participates in.

The Christian View

In the Christian understanding, the anamnesis is expressed in a very simple manner: the congregation, the ecclesia, reminds itself of what God has done, and also reminds God of his actions and promises, just as was the case with the sacrifices in the temple. The Christian understanding of anamnesis or zikkaron is therefore, as one may expect, intimately connected with the celebration of the Lord's Supper, the Eucharist. It is an integral part of almost all anaphoras (Eucharistic prayers). The words of our Lord in the institution of the Last Supper end with, "Do this in remembrance of me," and the anamnesis usually continues in such manner as can be found, for instance, in the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom:

Remembering, therefore, this command of the Savior and all that came to pass for our sake, the cross, the tomb, the resurrection on the third day, the ascension into heaven, the enthronement at the right hand of the Father, and the second, glorious coming. . . .

In the Roman Canon, the wording of the anamnesis is, "Father, we celebrate the memory of Christ, your Son. We, your people and your ministers, recall his passion, his resurrection from the dead, and his ascension into glory."

In the liturgy of the Church of Sweden, there is in one of the Eucharistic prayers a kind of "double anamnesis." After the words of institution, the priest prays or sings, "Therefore we celebrate this mystery of faith," and the congregation answers, "Your death, Lord, do we proclaim, we confess your resurrection until your return in glory." The priest then continues, "Holy Father, we celebrate this meal in commemoration (åminnelse) of your Son's passion and death, resurrection, and ascension. You have given us the bread of life and the cup of blessing to eat and drink until the day he will return in glory."

There is no verbal conformity between the various prayers of anamnesis, but the substance remains the same. It is, in this regard, easy to recall the Rule of Faith, which is flexible in its wording but constant in its content. It is also quite obvious that what the anamnesis recalls is nothing but the content of the second article of the Creed (or for that matter, the central part of the Te Deum). This should not surprise anyone, because the events from the Annunciation to the Ascension are the culmination of the divine saving action that started at the Exodus (or earlier in the calling of Abram, or earlier yet with the Protoevangelium in Genesis 3:15).

Action of the One God

In one sense, Jews and Christians remember and recall the same divine saving action and celebrate the same sacred history, the main difference being that the Jews are still expecting the Messiah to come, whereas Christians confess Jesus of Nazareth as the Messiah who has come once and who will return. In this latter sense, both Jews and Christians share the same hope and expectation: the coming of the Messiah.

Even a superficial knowledge of the Jewish Maggid, the retelling of sacred history at the celebration of Pascha, will prompt a Christian to say that this is a part of his history, too. It is a part of God's great saving economy for the world that he created, his oikonomia. In this economy of salvation, the coming of the Messiah, the Incarnation of the Second Person of the Holy Trinity, the Son of God, the divine Word, and divine Wisdom, is the culmination and apex.

The blessing that God promised to Abraham, the promise that he would be the father of a people as numerous as the stars in the sky, and as the grains of sand on a beach, has been fulfilled in the sending of the Son, not only for the restoration of Israel, but for the salvation of all mankind. The Messiah, through his circumcision, was truly a member of God's people, but by reason of his true manhood, his genome, he belongs to all humanity, and it is also with regard to humanity that his mission, his person, and his work are to be interpreted and understood.

The Christian Shema, that is, the Creed, agrees with the Jewish confession of one God and one God only to be honored and worshiped. Christians have taken seriously God's words at the epiphany for Moses at the burning bush, when God revealed his name in the sending of Moses. It is a majestic and enigmatic name. God reserves the privilege to be who he is without revealing his identity entirely: "I am who I am." He is there, fully present in what he does, but his identity remains open, as if he were saying, "You will learn who I am by being with me, by listening to me, by obeying my commandments, and by seeing what I am doing now and will do in the future!"

Christians must tolerate the humiliation of being unable to present their God as someone easily understandable. They have to talk about him as one God, and yet come to terms with and try to express their experience of God as three persons or hypostases, Father, Son, and Spirit, in a Trinity, a oneness in communion. This is not something that is revealed through a philosophical meditation after an anamnesis of the immortal soul and katharsis of the senses, as would have been the case in Platonic thought. God has himself revealed in his actions that he is Father, Son, and Spirit. This is the only way—humbling as it may be to human logic—to express the Christian experience of God's action in the world.

Father, Son & Spirit

In the third article of the Nicene Creed—the concise and precise summary of biblical revelation—the Holy Spirit is confessed as the one who exercises lordship and gives life; it is also confessed that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and is worshiped and glorified together with the Father and the Son. This means that the Spirit is as much God as are the Father and the Son.

There is one special activity confessed about the Spirit—he "spoke through the prophets." The Holy Spirit certainly does many things, but why is this particular activity highlighted? The answer is that this passage gives the reason and justification for the Christian reading and interpretation of what we call the Old Testament. There are in Holy Scripture patterns (typos) and prophecies that have their perfection and fulfillment in Jesus Christ. He was the foretold and promised One. In Jesus Christ, the God who revealed his name, "I am who I am," has been pleased to reveal more of his identity through his actions.

Christians must say that one cannot talk about the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, the God of Moses, the God of the Exodus and the covenant on Mount Sinai, the God of David and the kings, the God of the temple and the prophets, without talking about Jesus at the same time. God-talk without Jesus-talk is, for a Christian, meaningless.

God's saving action, which is at the center of the zikkaron of Pascha, is the sending of the Son. Once that is said, one has to go on with the Christian Maggid (if I may put it that way). This retelling of the Christian Exodus story for the whole of mankind coincides with the content of the second article of the Creed and the anamnesis prayer at the Eucharist.

If it is true what is said about Jesus Christ, and what the Christians claim—that the Jesus-story, who he is and what he did, is true—and, if it is true that God the Holy Spirit has inspired the Holy Scriptures and given his stamp of approval to the Christian interpretation of the Old Testament, then we have arrived at God's ultimate saving action in the oikonomia—or, if we wish to recall Plato, the Absolute—with the very important difference that the sending of the Son, the Incarnation of the divine Logos, pertains to all that is, both visible and invisible.

The Word became flesh! God became man. God, the Creator, entered the world in the Son, through whom everything had come into being. He entered into his own creation, sharing its conditions, and by doing this, he not only gave his approval to all that is created, but also, in a cosmic act of deliverance, he liberated it from all the kinds of bondage in which it was held by sin, death, and the devil. This is the great exodus for all mankind.

No part of what Jesus says or does, nothing of what he is—true man and true God—may be abstracted from the confession about him, because the confession expresses the truth, the ontological reality. Such a removal would be like extracting the active ingredient from the medication that is the effective antidote against snake venom.

Extended Anamnesis

The Cross at Golgotha is the apex and the visible culmination of the Incarnation, and as such, it may stand as a pars pro toto, a part representing the whole. At Golgotha, the Old Covenant in blood meets the New Covenant, also in blood, but in this case not the blood of rams and bulls, but the blood of the Lamb of God. At Golgotha, various parts of the Old Testament imagery meet and blend, as in a photographic double, or even triple, exposure. Jesus himself consciously interpreted his death in terms of sacrifice and exodus, as is clearly evident in his last meal with his disciples. He is the new way to God, not only for the Jews in the Old Testament, but for all mankind. His words are very clear: Do this—take and eat, take and drink—in remembrance of me—this is the new Testament, the new Covenant in my blood.

What happens here is the work of the triune God according to the triune premise in Christian doctrine, opera ad extra trinitatis indivisa sunt, which is to say that all works of God outside the immanent communion of the members of the Godhead with each other is common to all three Persons. The God who created is the God who atones and liberates, and the God who liberates and atones is the God who gives life and sanctifies. The salvation history recorded in the Old Testament is the work of the Triune God.

In the Church Orders,associated with Hippolytus and dating from the beginning of the third century, the Eucharist is celebrated in connection with the consecration of a new bishop. It is instructive to see how the episcopal ministry and the Eucharist are tightly knit. They both belong to God's saving action and provision for man. There is in the liturgy a reference to Abraham and to those who ministered in the temple, as well as to the apostles that were sent by Christ. They all belong to God's oikonomia.

In the anaphora, this becomes even more manifest. The bishop of the congregation prays:

We give thee thanks [eucharistomen], O God, through thy beloved Servant Jesus Christ, whom at the end of time thou didst send to us as Savior and Redeemer and the Messenger of thy counsel. Who is thy Word, inseparable from thee, through whom thou didst make all things, and in whom thou art well pleased. Whom thou didst send from heaven into the womb of the Virgin, and who, dwelling within her, was made flesh, and was manifested as thy Son, being born of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin. Who, fulfilling thy will, and winning for thee a holy people, spread out his hands when he came to suffer, that by his death he might set free them who believed on thee. Who, when he was betrayed to his willing death, that he might bring death to naught, and break the bonds of the devil, and tread hell under foot, and give light to the righteous, and set up a boundary post, and manifest his resurrection, taking bread and giving thanks to thee said, "Take, eat, this is my body which is broken for you." And likewise also the cup saying, "This is my blood, which is shed for you. As often as ye perform this, perform my memorial." Having in memory [italics mine], therefore, his death and resurrection, we offer to thee the bread and the cup, yielding thee thanks, because thou hast counted us worthy to stand before thee and to minister to thee. (Burton Scott Easton, trans. and ed., The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus [Cambridge Univ. Press, 1934], p. 36.)

The whole anaphora is, in fact, an extended anamnesis; it recalls God's savings deeds in history—the oikonomia with its culmination in the mission, the person, and the work of Christ. It is a zikkaron, a remembrance, a reactualization, a representation of who he is and what he has done. Those partaking are not only witnessing something from the past, but are themselves drawn into God's present through participation in the liturgical action, through the celebration. God is talking to, acting with, and even feeding his chosen people at this very moment.

Epiclesis & the Spirit

In immediate conjunction with the words of institution and the anamnesis in a narrower sense, there follows in Hippolytus's liturgy the prayer for the Holy Spirit, the epiclesis, of which the theme of the unity of believers is an integral part:

And we pray thee, that thou wouldst send thy Holy Spirit upon the offerings of thy holy church, that thou, gathering them into one, wouldst grant to all thy saints who partake to be filled with the Holy Spirit, that their faith may be confirmed in truth, that we may praise and glorify thee.

In an Anglican version, the epiclesis is:

And we offer our sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving to you, O Lord of All, presenting to you, from your creation, this bread and this wine. We pray you, gracious God, to send your Holy Spirit upon these gifts that they may be the Sacrament of the Body of Christ and his Blood of the new Covenant. Unite us to your Son in his sacrifice, that we may be acceptable through him, being sanctified by the Holy Spirit. . . .

In the Church of Sweden one of the epicleses reads:

Send your Holy Spirit into our hearts that he may kindle a living faith. Sanctify also through your Spirit this bread and wine, gifts of the fruit of the earth and man's labour, which we offer to you, and let us through them partake in the body and blood of Christ.

The anamnesis refers to the fact, and the epiclesis (or rather the Holy Spirit as a result of the supplication in this prayer) makes this fact a living reality here and now for the participants. There is an analogy here to the occasion when Elijah asked God that the fire would fall upon the altar in his contest with the prophets of Baal (1 Kings 18:30–39). The Spirit kindles faith, and with Christ's words of institution (the anamnetic element), brings about the transformation of bread and wine into Christ's Body and Blood. It becomes a living reality for us here and now in the celebration of the congregation.

Epiclesis & Unity

There is in the Swedish church order for the Eucharist a part in the anaphora that takes up and carries on the epiclesis. There is a anamnetic petition that makes reference to Christ's work on Golgotha, "We pray to you: behold his perfect and eternal sacrifice, with which you have reconciled the world with yourself," and then the epicletic element reoccurs: "Let us all through the Holy Spirit be united into one Body and perfected into a living sacrifice in Christ."

The theme of the unity of believers is also an integral part of this prayer; through baptism believers are already incorporated into the mystical Body of Christ, but it remains something to pray about: for a deepening realization of an already existing fact.

Before the Agnus Dei and the Greeting of Peace, the priest makes this scriptural proclamation, holding the consecrated wafer in his hand: "The bread which we break, is it not a communion of the body of Christ?", and the congregation answers, "For we, being many, are one bread and one body, for we are all partakers of that one bread" (1 Cor. 10:16–17). The physical partaking of the one broken bread among those who, through baptism, have been incorporated into the Body of Christ is a participation in his sacrificed, resurrected, glorified, and ascended Body; and this participation means a communion between the participants and Christ, and, in Christ, a communion between all the participants.

The Eucharist is the focal point and the locus of the visible unity of all Christians. There is in the epiclesis an explicit prayer for unity. The Spirit is asked to make the believers one body united with Christ in his self-offering and sacrifice. Union with Christ in his self-offering and sacrifice is the ultimate unity.

If the anamnesis is what it is supposed to be, referring to the second article of the Creed (because that is the content of God's saving action, the Absolute truth in Platonic thought), and if the congregation, through the celebrant, in the epiclesis invokes the Holy Spirit in its liturgical celebration of God's mighty actions in his oikonomia (divine economy), asking the Spirit to come, to vivify, to "light the fire," then surely the congregation in its worship, with the Eucharist at the center, expresses the tangible and visible unity of the Christian Church, for each member is a part of the ongoing exodus of God's humanity. There the Church is as visible and tangible as the Incarnate Son of God and Son of Man was, when he sojourned on this earth.

The Scope of Salvation

Plato's mouthpiece Socrates believed in the immortality and possible return of the soul in transmigration. He also believed that the soul, through anamnesis and katharsis, could realize its participation in the Absolute in the forms of Truth, Goodness, and Beauty. But that was only for the soul. Man's bodily reality in createdness was excluded. Plato's view was purely docetic.

In the Jewish view, God's people, through a recollection of the Exodus, re-present God's mighty deeds in salvation history with Israel, the people whom he freed from bondage in Egypt to a promised land of their own. The focus was on Israel.

In the Christian faith, God's action in history is taken one step further, through the Incarnation. His saving will and action are for the whole man—body, soul, and spirit—not only for an immortal soul. And they are not only for one chosen nation, but are extended through that nation to the whole of mankind. All this is grounded in his creation of man: the Creator is the Liberator and the Consummator of a redeemed and perfected creation.

God's original will and design for man was that he who was created in the image of God (imago Dei) should attain to the likeness of God (similitudo Dei). If man had obeyed God and remained in his will, he would eventually have reached that goal. But he wanted to grasp this godlikeness prematurely and on his own conditions. He wanted to be like God, without God. This is the Fall, which brought disaster over the whole creation. Through his disobedience and pride, man's identity and character were deformed. The process of growing into godlikeness was thwarted and had to be realized in another way. This is where the plan and action of redemption starts. God recapitulates the story, not in Adam, man, but now in the Son, Christ. Christ, the incarnate God, reaches and rectifies what man perverted and missed.

Through the Incarnation of the Son of God, the whole of history is set right in and through Christ, the perfect man. Through his life and death, his sacrifice, mankind is liberated from the bondage of sin, death, and the devil. Its guilt has been atoned for through a perfect and eternal sacrifice that stands in the middle of the cosmos and occupies, in a manner of speaking, the place of Plato's Absolute (which I think is also included in the Person and work of Christ). From Adam to Abraham, from Abraham to Israel, from Israel to the Church, from the Church to Mankind—that is the scope of God's oikonomia.

The Saving Word

The Christian anamnesis,then, is nothing less than the claiming of God's mighty, salvific work in Christ. And its epiclesis is the humble prayer that this fact will become a living reality for the ecclesia, and for each believer in the celebrating community through the life-giving activity of the Holy Spirit.

At the eve of his execution, Socrates talked with his friend Simmias about his imminent death as something not to be feared, but rather to be welcomed. He compared his situation with that of the swans: they sing more beautifully than ever when their death is approaching, "because they know the good things that await them in the unseen world" (Phaedo, 85b, CDP, p. 68).

Simmias is far from convinced, believing it impossible or at least extremely difficult to obtain sure knowledge of these matters in this life. Yet, one must try and do one's best, sailing though the waters of life on the raft of words that one has, "unless we might make the journey on a securer stay—some Divine Word, if it might be . . ." (Phaedo, 85d, quoted from B. F. Westcott, "The Myths of Plato" in Essays in the History of Religious Thought in the West [MacMillan, 1891], p. 50).

B. F. Westcott concluded, "The Word for which the wavering faith of Simmias thus longed, has, we believe, been given to us; and once again Plato points us to St. John."

Folke T. Olofsson is docent of theological and ideological studies at Uppsala University, and is rector of Rasbo parish in the (Lutheran) Church of Sweden. He is a contributing editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on history from the online archives

15.6—July/August 2002

Things Hidden Since the Beginning of the World

The Shape of Divine Providence & Human History by James Hitchcock

14.6—July/August 2001

The Transformed Relics of the Fall

on the Fulfillment of History in Christ by Patrick Henry Reardon

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor