View

Pupils Delighted

Anthony Esolen on Wondering or Wandering Through College Education

This spring at our college’s awards ceremony I was sitting next to the father of one of my brightest students. His son was graduating in biology, summa cum laude. But that’s not what the father wanted to talk to me about. He wanted to express his gratitude for my being a kind of spiritual guide for his son.

If I did guide his son, it was indirectly, by introducing the young man to some of the glorious poetry of the Christian world. I don’t know that he needed such guidance; he is uncommonly wise for one of his years. But it was my privilege to be the person who led him to the beauty and the wisdom of the works of Dante and Milton, of Spenser and Shakespeare.

And there was more. The father was grateful also because his son brought home with him that beauty and wisdom, and it buoyed up the good man during difficult times, when he was tempted, as he put it to me, to “pack it in.” Then he showed me a card in his wallet, of Jesus of the Sacred Heart, with the white and red rays, signs of love and mercy.

So there we sat as the ceremony proceeded. Then it came time to honor this year’s recipient of the college’s teaching award. This professor is a friendly fellow, scrupulous in his work, and well liked by students in his field. He’s also someone who has no admiration whatsoever for the humanities. He’s spent two or three decades deriding our college’s two-year course in Western Civilization. He runs it down in his classes, in the presence of students enrolled in the course. He’s been known to pick on students publicly for studying poetry, which he calls useless. His outlook is entirely secular.

I expected to wince. Instead, what I heard puzzled me. I am still trying to understand it. He congratulated the students for being part of the “most selective freshman class in the last ten years.” He congratulated them for their being what he called “engaged learners,” unlike freshmen at our school thirty years ago—many of whom, it should be noted, were present in the audience and pay his salary—who were “passive learners,” taught merely to memorize information from lectures. That last was an ill-bred and ill-informed slap at our Western Civilization course.

He concluded his short acceptance speech by declaring that he had no doubt that the honorees in attendance would make us proud. This they would do by “earning high scores on standardized tests,” or “obtaining internships and fellowships,” or “distinguishing themselves in musical or theatrical competitions,” or “winning admission to prestigious graduate schools.”

As Milton’s Belial says in Hell, “And that must end us, that must be our cure.”

Unaware Amputees

I am not much puzzled by the emptiness of the secular world, its pious slogans and self-congratulatory politics (here, as it happens, politics of the left) little more than a flourish upon cold, meritocratic ruthlessness. I concede that it does still shock me when I see it up close. I imagine that it still surprises an army surgeon to see a man with no legs stilting into his office. These here are spiritual amputees. I wish they weren’t, just as the surgeon might wish that the man with the prosthetics had his own legs again.

But what does puzzle me is the utter lack of awareness. A man born blind does not know what it is to see, but he’s heard of vision and he knows that he lacks it. A man with no legs may well remember what it is like to walk. But—in my experience—the secularist does not know what he does not know.

And that, as I said, does puzzle me. How could this colleague of mine not be aware of the amputation? We are, after all, a Catholic college. There were priests on the dais. The ceremony began with a prayer. The president opened the speeches with a discussion of Thomas Aquinas and honor. Mass would be celebrated later in the afternoon.

And, as is always the case at such ceremonies, there were those things called people in the audience, a lot of sinners and maybe a saint or two, old people watching the sun go down on their lives, children without a care in the world, husbands and wives more deeply in love with one another than when they were first married, others embarrassed and uneasy, some people contented and rich, others miserable and rich, some people searching for Jesus, others running away from him. And at this moment, all that you the secularist can talk about are the trappings of success, and some academic twaddle about being “lifelong learners.” But about what you learn, and what life you lead, and where you are going, nothing. The secular life seems to me like one of those European road races that begin and end in the same city—a frenetic grand prix to get from Brescia to Brescia.

A few days later I opened the monthly magazine of my mater ferox, the Princeton Alumni Weekly. I always open the monthly Weekly to the back where the class notes are, just in case they mention one of my old friends. I also look at the obituaries. Then I file the Weekly in its receptacle under the kitchen sink.

This time I read several of the obituaries, combing through them to see if I could find a single reference to the faith of a Princetonian, his devotion to God made manifest in his love of family and neighbor. Nothing, not from the class of 1939 clear to the class of 1990. It is as if that whole dimension of human life—some people call it depth; I call it reality—did not exist. Instead, the obituaries were full of the usual praise for worldly achievements. Everyone is supposed to do Very Important Things, like acing a standardized test or winning a piano contest or publishing in Harvard Law or being elected Speaker of the House for South Dakota. No one is eulogized for merely loving a spouse and children, and certainly not for bending his knees in prayer.

Making Lovers of Wisdom

And yet—something else happened to me this spring. It is something that my student and his father would understand, and that might someday move them to tears, if they should come upon this article, which I write with love and admiration. A man had spent a half-hour at the bedside of his old professor, who was dying, and who was not aware of his presence. He said a decade of the rosary there.

He was moved to write to me, a stranger, to tell about his experience. I trust I am not revealing a confidence. This person, this former student, sent to me a copy of the brochure that he received when he entered something called the Pearson Integrated Humanities Program, at the University of Kansas, in 1974.

I can hardly look at the cover page without wanting to weep, it is so achingly sweet, so emblematic of how much we have lost. An old man in the foreground, mounted on a swaybacked and skinny horse, wielding a lance and a buckler, looks up at the stars—at Ursa Major and Polaris. It is clearly Don Quixote and poor old Rocinante. The stars are framed by a Roman triumphal arch, whose frieze is decorated with scenes from ancient Greece: a man teaching a youth to play the zither; a naked sprinter; a chariot race; a woman dancing; and two Muses with stringed instruments. Below them, on the sides of the arch, are two medallions, one depicting a medieval monastery, the other, what I’m guessing is the cupola to Independence Hall.

The Pearson Integrated Humanities Program must have violated every educational truism of our time. Two hundred freshmen and sophomores, for six hours a week for two years, sat in the company of three professors, John Senior, Frank Nelick, and Dennis Quinn, who discussed art, poetry, music, history, philosophy, and Scripture with one another, while the students overheard them and eventually learned to participate in the discussions themselves. The students also recited poetry, learned to waltz, and were introduced to such words as truth, faith, honor, love, courtesy, decency, simplicity, and modesty, not words much used in an Age of Iron, but then, Don Quixote was sent into that time precisely to bring back something of the Age of Gold.

The motto of the program was Nascantur in Admiratione, “Let Them Be Born in Wonder.” One of the pages of the brochure explains why:

In our day wonder has been so cheapened by sensationalism and so crippled by skepticism that the college freshman, instead of being as one newly awakened to the excitement of learning, is often, rather, as one who has never been born. To such a young person learning is so much drudgery and routine, alien to his real interests, remote from reality itself. To revive wonder may be said to summarize the aims of the Pearson Program. Hence it should be regarded as an elementary or elemental course, where one discovers the love of wisdom; a course for beginners, who look upon the primary things of the world, as it were, for the first time.

An ancient philosopher said that to look at the stars is to become a lover of wisdom—a philosopher. Since the Pearson Program aims to make all students philosophers in that sense, we say, with a modern poet, “Look at the stars! Look, look up at the skies!” Not only are students in the program required to look, literally, at the stars, but they are also expected to look up through poetry and through all that is great in Western civilization. It is by the light of the stars (or “something like a star”) that we discover the world, ourselves, and our destination.

Smitten by Wonder

In my halting and often confused way, I hope that I have been trying, these twenty years and more, to lift up the hearts of my students, that they, too, might see a star or two. But these three professors, these three good and faithful men, did far more. They inspired hundreds of students to continue in their vision. Many converted to the faith. Some became priests or nuns or monks. Some went on to found their own schools, elementary and secondary schools and colleges, based upon the humane love of God and of God’s world that they found in their teachers at the University of Kansas, and in the art and poetry they learned there.

Naturally, such a program could not be allowed to continue, and indeed the university trustees shut it down after about ten years. But the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church. These men brought beauty to the young people they met. Those students still honor them. The student who went to see his beloved professor writes that their faith lives on, and he mentions a few prominent churchmen who graduated from the program, and also “the moms and dads, teachers, lawyers, carpenters, farmers, doctors, accountants and whatever else, people smitten by wonder, whose lives were changed." (emphasis mine).

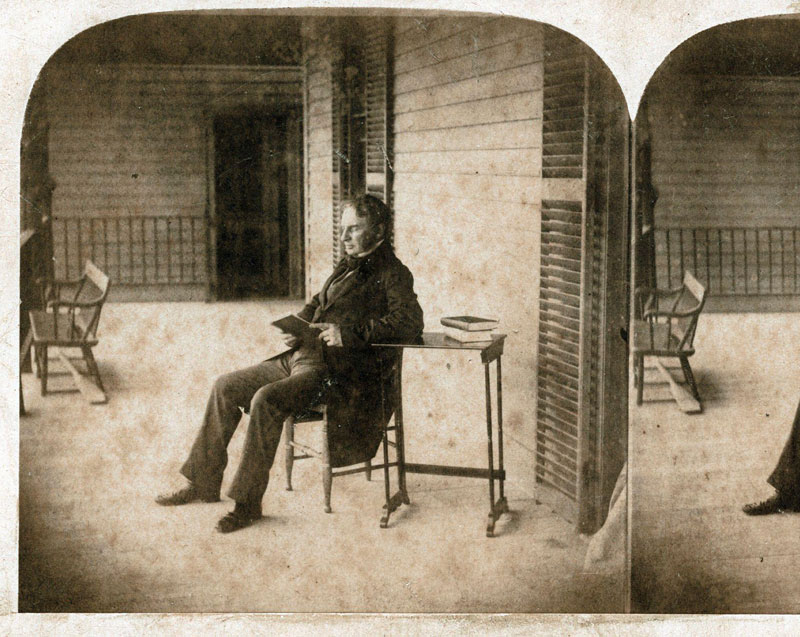

I am looking at a photo of Dennis Quinn. He looks fairly young, with curly blond hair and spectacles. He’s wearing a coat and tie, and is gesturing with an open palm as he speaks to the student at his side. They are walking across the campus. The student, with long, curly black hair and a print shirt, is evidently thinking about things—he is carrying books in one hand, with the other placed on the back of his head, which is bowed.

It is this vigorous man, Professor Dennis Quinn, who lay dying, “in whom the light of life was flickering,” as my correspondent writes. Professor Quinn passed away at about six in the evening, March 15, 2011. He was the last of the three professors to die.

Turning Eyes Starwards

What, finally, is the point of education? My colleague on the dais says that a man without data is just somebody else with an opinion. Not much room for wisdom there, or for those things that data cannot capture, such as beauty and goodness and truth, which are deeper than facticity. He measures the success of education in material terms; or perhaps I should just say he measures its success.

I can’t pretend to be as good a teacher as Dennis Quinn was. I’m guessing that a lot of things have slipped since. But the faith teaches me. It shows me that my work as a teacher is to be a kind of forerunner, to be someone who turns the attention of his students to things that, on my own, I cannot comprehend—the true, the beautiful, and the good: contemplata aliis tradere, “to hand on the fruits of contemplation to others.”

One last anecdote, one that I believe Professor Quinn, and my wise student and his father, would appreciate. A woman wrote to me this spring quite out of the blue. She had graduated in 1992, and had taken a class or two of mine in Renaissance literature. Then I taught her brother, a lovable rascal, several years later. She had read my monthly reflections in the Catholic missal Magnificat, and felt moved to thank me and to send a picture of her family. She’s a devout and joyous Christian—not a winner of some competition, not a doctor or a lawyer or an Indian chief, but the mother of a brood of eight beautiful children.

I will be taping the picture to my office wall. When I think of her, and of students like her, so many fine people, I hope that I’ve been able to turn their eyes starwards. And when the time comes, and the great and mysterious final change is coming upon me, I hope that some one of them will visit me at my bedside, and say those things the world will never understand. •

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on education from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor