Regensburg Left Behind

Christians Responding to Muslim Invitations Haven’t Been Listening to Benedict XVI

by J. Daryl Charles

Few will forget the uproar among Muslims worldwide that was precipitated in September 2006 by Pope Benedict XVI’s address at the University of Regensburg. In this address, titled “Faith, Reason, and the University: Memories and Reflections,” Benedict combined personal reflections on teaching theology at the University of Bonn decades earlier with his assessment of the state of contemporary academic discourse. In retrospect, Benedict’s personal experience in the professoriate strikes the reader as cause for great satisfaction. Benedict recalled:

We would meet [at the university] before and after lessons in the rooms of the teaching staff. There was a lively exchange with historians, philosophers, philologists, and naturally, between the two theological faculties. Once a semester there was a dies academicus, when professors from every faculty appeared before the students of the entire university, making possible a genuine experience of universitas . . . the experience, in other words, of the fact that despite our specializations which at times make it difficult to communicate with each other, we made up a whole, working . . . on the basis of a single rationality with its various aspects and sharing responsibility for the right use of reason. . . .

Benedict noted the significant role of the university’s theological faculty, since “by inquiring about the reasonableness of faith, they too carried out a work which is necessarily part of the ‘whole’ of the universitas scientiarum, even if not everyone could share the faith which theologians seek to correlate with reason as a whole.” “This profound sense of coherence within the universe of reason,” Benedict insisted, “was not troubled, even when it was once reported that a colleague had said there was something odd about our university: it had two faculties devoted to something that did not exist: God.”

It is still necessary, Benedict continued, particularly given the prevalence of radical skepticism in our day, “to raise the question of God through the use of reason, and to do so in the context of the tradition of the Christian faith” (emphasis added). He reminded his German audience that this activity, though currently unfashionable, was “accepted without question” only decades ago within the university as a whole.

Born of the Soul

Of course, much has changed in the decades since Benedict (at the time, Joseph Ratzinger) taught at the University of Bonn. Several interlocking factors have emerged to complicate the task of teaching the reconciliation of faith and reason in contemporary Western culture in general and in the European context in particular. One such factor is Europe’s advanced (and often critiqued) secularization and the attendant hostility toward its own religious-cultural history. One need only recall the fierce debate some years ago over whether to include any religious references in the European Union’s constitution. This element is compounded by another significant development—demographic in nature and by now well-advertised as well—which finds large numbers of Muslims immigrating to Europe and, in contrast to most Europeans, vigorously pressing their own faith claims.

It is important to bear these two factors in mind, for they assist us in understanding the agitated response that followed Benedict’s Regensburg address. Wishing to illustrate the symbiotic relationship between faith and reason, the pope compared the “structures of faith” as taught in Christianity with those taught in the Qur’an. Acknowledging, by way of historical example, the differing attitudes toward faith in the two religions, he stressed that compulsion “is incompatible with the nature of God and the nature of the soul.”

The biblical witness, he reminded his audience, is marked by the fact that faith is “born of the soul, not the body.” Therefore, “whoever would lead someone to faith needs the ability to speak well and to reason properly, without violence and threats. . . . To convince a reasonable soul, one does not need a strong arm, or weapons of any kind, or any other means of threatening a person with death.” “The decisive statement” in this argument against forceful conversion, Benedict concluded, is this: “not to act in accordance with reason is contrary to God’s nature.”

For some, the thesis that faith and reason are symbiotic and that faith cannot be coerced is rather non-controversial. But to others in the Regensburg audience and to Muslim representatives worldwide, a nerve had been struck. Not a few Muslim leaders demanded an apology from Benedict. One month after the address, a group of 38 Muslim leaders wrote the pope an open letter that attempted to correct perceived errors in his representation of Islam while calling for greater mutual understanding between Muslims and Christians.

“A Common Word”

Precisely one year after Regensburg, in October of 2007 at the end of Ramadan, a second open letter, signed by 138 Muslims representing diverse theological traditions and titled “A Common Word Between Us and You,” was addressed—and hand-delivered—to the pope, as well as to 26 other “Leaders of Christian Churches,” including Bartholomew I, the Orthodox Church’s Patriarch of Constantinople, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams. This particular document, produced at the initiative of the Aal al-Bayt Institute for Islamic Thought, which seeks to represent Islamic interests to governments and international bodies, called for dialogue on the basis of what was claimed to be common theological ground between the two faiths.

Part of the document’s stated rationale is that “Muslims and Christians together make up well over half of the world’s population. Without peace and justice between these two religious communities, there can be no meaningful peace in the world.” “The future of the world,” the signatories stressed, “depends on peace between Muslims and Christians.” Moreover, “the basis for this peace and understanding already exists” and is “part of the very foundational principles of both faiths: love of the One God, and love of the neighbor.”

What, specifically, is said to be the basis for “peace and understanding” between Muslims and Christians? According to the open letter, “the Unity of God, the necessity of love for Him, and the necessity of love of the neighbor” are “common ground” between Muslims and Christians and “the basis for all future interfaith dialogue.” This is a remarkable claim and thus requires a discerning and theologically nuanced assessment.

Structurally, “A Common Word” consists of three parts: (1) “Love of God” as demonstrated in Islam and the Bible, (2) “Love of the Neighbor” as demonstrated in Islam and the Bible, and (3) a concluding exhortation to “Come to a Common Word Between Us and You.” In each part, examples are drawn from both the Qur’an and the Bible to support this claim of common ground. It is noteworthy, however, that only the Synoptic Gospels are cited as evidence of the document’s central claim; the fourth Gospel, Acts, and the entire corpus of New Testament epistles are conspicuously absent, while the Old Testament is all but ignored.

Significant claims are set forth in the document that both merit consideration and call for a thoughtful response on the part of any morally serious reader. The most important of these are summarized as follows:

• “[I]t is clear that the Two Greatest Commandments are an area of common ground and a link between the Qur’an, the Torah and the New Testament.”

• “Thus the Unity of God, love of Him, and love of the neighbor form a common ground upon which Islam and Christianity (and Judaism) are founded.”

• “God confirms in the Holy Qur’an that the Prophet Muhammad brought nothing fundamentally or essentially new.”

• “In the Holy Qur’an, God Most High tells Muslims to issue the following call to Christians (And Jews—the People of the Scripture).”

• “Muslims, Christians and Jews should be free to each follow what God commanded them.”

• “As Muslims, we say to Christians that we are not against them and that Islam is not against them—so long as they do not wage war against Muslims on account of their religion, oppress them and drive them out of their homes.”

• Muslims “recognize Jesus Christ as the Messiah, not in the same way Christians do (but Christians themselves anyway have never agreed with each other on Jesus Christ’s nature). . . . We therefore invite Christians to consider Muslims not against and thus with them, in accordance with Jesus Christ’s words.”

• Finally, “as Muslims, and in obedience to the Holy Qur’an, we ask Christians to come together with us on the common essentials of our two religions . . . that we shall worship none but God, and that we shall ascribe no partner unto Him, and that none of us shall take others for lords beside God.” This tripartite statement, which occurs several times in the document, is a key to the document’s interpretation and is made on the basis of numerous citations from the Qur’an.

The Yale Response

One month after the appearance of “A Common Word,” several members of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture, part of the Yale Divinity School, drafted a response to the document under the title “Loving God and Neighbor Together: A Christian Response to ‘A Common Word Between Us and You.’” To lend visibility to this “Christian response,” a full-page ad was taken out in the New York Times. By January of 2008, the number of signatories to the “Yale Response” had swelled to 300.

While some of these signatories were Catholic, the vast majority were Protestant, many of them representing wider Evangelicalism, including such notables as Richard Schuller, Dudley Woodberry, Richard Mouw, Richard Cizik, Timothy George, Bill Hybels, Rick Warren, Nicholas Wolterstorff, David Neff, John Stott, Glen Stassen, Leith Anderson, Duane Litfin, and Stanton Jones. (To my knowledge, Litfin and Jones were the only leaders who, later reflecting on the actual content of the documents, had their names removed from the Yale Response.) Lutheran, Methodist, Episcopal, Presbyterian, Church of Christ, Assemblies of God, Mennonite, and Baptist leaders were among the signatories, as well as leaders of interdenominational and mission groups such as the National Association of Evangelicals, the World Evangelical Alliance, Operation Mobilization, Youth with a Mission, Frontiers, and the Overseas Ministries Study Center. In addition, a stunning array of lecturers, professors, and presidents of leading seminaries and divinity schools, such as Princeton, Yale, Harvard, Hartford, and Fuller, appeared on the list.

Significantly, the Yale Response offers no theological assessment of the claims of “A Common Word,” nor of Christianity’s own unique claims. Rather, its purpose is to acknowledge with “A Common Word” the need for religious and world peace, and to extol the “deep insight and courage” of the 138 for identifying common ground between Muslims and Christians—common ground, it states, in “fundamentals of faith,” in “love of God,” and in “love of neighbor.”

Official reactions to “A Common Word” from diverse institutions, mission groups, and denominations were almost uniformly (and stunningly) positive. The document was hailed as “historic,” “remarkable,” “astonishing,” and “unprecedented.” So, for example,

• The Archbishop of Canterbury noted that the letter “rightly makes it clear that these are scriptural foundations equally for Jews, Christians and for Muslims, and are the basis for justice and peace in the world.” He also declared that he was prepared to “do my part in working for the righteousness which this letter proclaims as our common goal.”

• One German theologian declared that there had never been an initiative like “A Common Word” in 1,400 years of Muslim-Christian history.

• The president of the Baptist World Alliance hailed the open letter as a “groundbreaking initiative” that could further “the cause of religious liberty and global peace.”

• The director of Cambridge University’s Inter-Faith Programme declared the open letter to be a “historic template for the future” and “an astonishing achievement of solidarity.”

• The president of the Lutheran World Federation applauded the sincerity of the Muslim signatories.

• And the editors of the Christian Century praised the Muslim scholars for their ability to exegete biblical texts and do “biblical word study”—a biblical word study, they pointed out, “that would shame most Christians.”

Taking Theological Claims Seriously

To deviate from these glowing responses to “A Common Word” might be perceived as uncharitable, for indeed, Christians have been waiting for this “historic moment” vis-à-vis Muslims for literally centuries. Given the relatively closed nature of Muslim culture, it has been incumbent upon Christians to do everything in their power to reach out to Muslims in Christian love. In the words of Dudley Woodberry, professor of Islamic Studies at the School of Intercultural Studies, Fuller Theological Seminary, because the Bible instructs us “to be peacemakers as part of our witness,” we must take the Muslim open letter seriously.

And indeed we must. But to take it seriously is to take its claims, its theological underpinnings, its representation of Christian theology, and its broad-ranging implications seriously. What, then, would the best Christian response be? In a column that appeared in Christianity Today, Woodberry asked Christian leaders to respond embracingly and without reservation to the overtures of the 138 Muslim leaders:

On the national and international level, evangelical leaders can join with other Christian leaders in signing a response written by members of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture . . . and having it published in one or more major newspapers where Muslims will see that, despite genuine differences between our faiths, Christians do not consider them enemies.

But both charity and theological integrity, I suggest, call Christians less to do public relations via newspaper ads with Muslims than to do what Pope Benedict and the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue have done; that is, to consider with utmost sobriety the integrity of the theological claims being made in the open letter. A serious reading of it, as well as of the Yale Response, brings to light substantive issues that, against the backdrop of both historic Christian faith and responsible statecraft, are problematic, indeed unavoidably so. Most of my observations concern not statecraft but theological affirmation.

Contrasting Doctrines of God

The open letter begins with two “creedal” affirmations, the sine qua non of Islam: There is no God but Allah, and Mohammad is his prophet. These tenets of faith, which undergird and govern the interpretation of “A Common Word” as a document, clash at the most basic level with historic Christian belief.

At the theological level, Christians and Jews categorically reject Mohammad as a prophet of God, which is both assumed and asserted in the open letter, thus governing its proper interpretation. The framers of the Yale statement might better have referred to Mohammad as “the founder of Islam” rather than conceding what historic Christian faith unconditionally and categorically rejects.

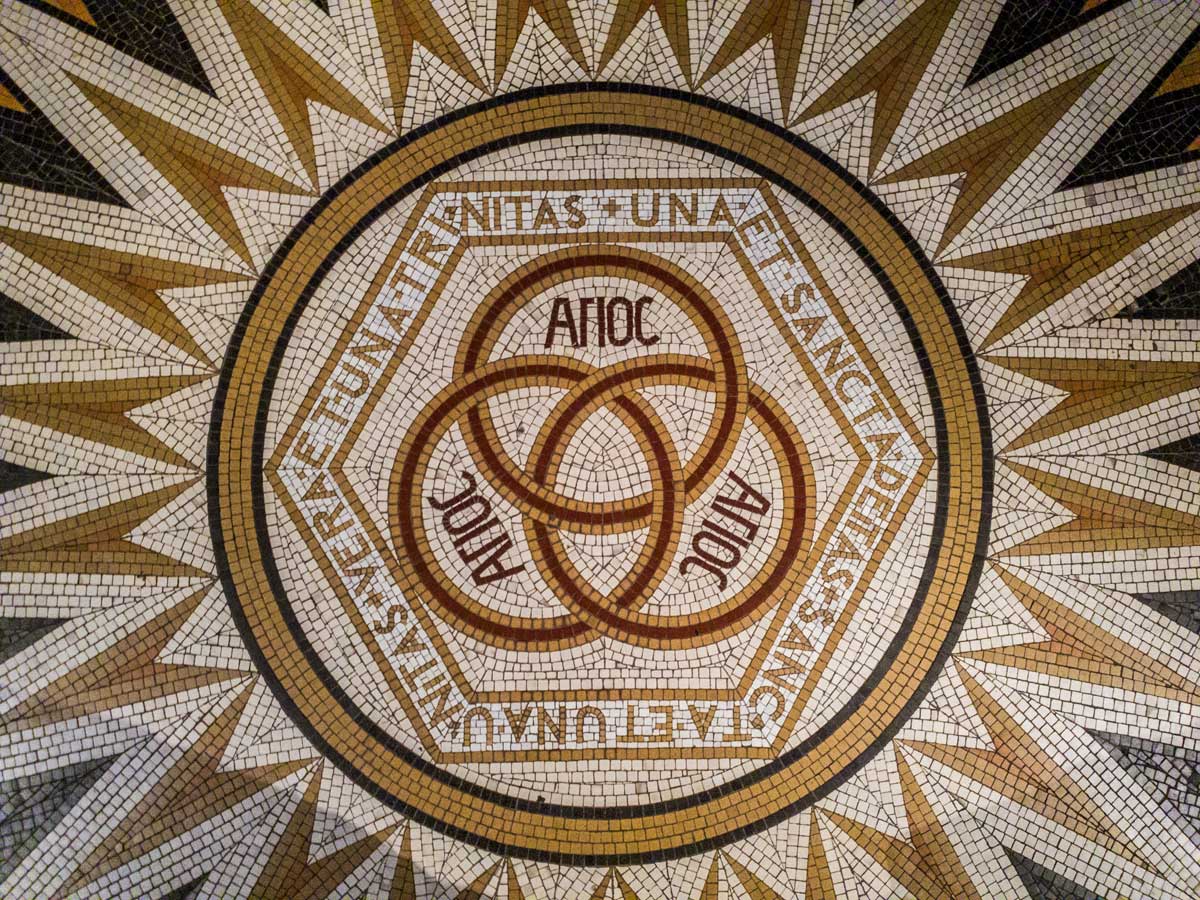

Conversely and in the same manner, when Christians invoke the name of God, they are invoking the name of Jesus Christ as Lord and God and cosmic Sovereign Ruler, and they do this in the framework of Trinitarian faith. Theological integrity, then, implies that, at the most basic confessional level, Muslims and Christians cannot be said to worship or call upon the same God.

Ultimately, both documents ignore the two contrasting metaphysics of God in the two religions. Although both Islam and Christianity posit a God of transcendence, of creation, and of judgment and mercy, Islamic theism is rooted chiefly (when not exclusively) in devotion, works, and ritualistic exercises of appeasement (as many of the Qur’anic texts cited in “A Common Word” in fact suggest). Most critically in this regard, Islam rejects outright the tenet that lies at the heart of Christian faith, namely, the notion of substitutionary atonement for sins, for the Qur’an declares that no one can bear the sins and responsibilities of another. Although the Qur’an speaks of Allah as “Most Beneficent” and “Most Merciful,” this mercy and forgiveness do not proceed through substitutionary atonement, by which transcendence combines salvifically with immanence.

Thus, the framers of the Yale statement, while well-intentioned and irenic in tone, ignore the most basic theological distinctions between Islam’s and Christianity’s doctrines of God, including Trinitarianism and Christology (that is, Christ’s preexistence, his incarnation, his substitutionary atonement, his resurrection, and his glorification or divine exaltation). Even while acknowledging, as I do, that there is common ground between the two religions, the reader wonders why, at the level of the theistic metaphysics, no qualifications are made in the Yale document. Whether this silence is inadvertent or deliberate, it has the effect of marginalizing Trinitarian faith, as well as the person, work, and cosmic lordship of Jesus Christ.

On the Ethics of Neighbor-Love

Correlatively, ethical questions are raised by both documents. While the concept of “neighbor-love” is distinctively Christian, it is difficult to discern this thread in Muslim teaching. To be sure, love for fellow Muslim brethren is enjoined repeatedly in the Qur’an. However, what is simultaneously striking is the place given to “disbelievers” and those outside the camp. The standard depiction of them in the Qur’an gives a reader the distinct impression that unbelievers are to be resisted or opposed both defensively and aggressively.

It would thus seem that the God of Islam cannot properly be said to love “unbelievers”; rather, they are despised—to be shunned at best and opposed or mistreated at worst. This understanding is mirrored by the standard designation of “infidel” (indicating those who, according to shari’a law, are to be subordinated and opposed), as well as by the legal dhimmi status to which Christians and Jews historically have been subordinated in Muslim culture (and according to which they lack equal or even basic human rights).

The related matter of “apostasy” graphically illustrates the differences in social ethics between the religions. Not a few Muslim scholars today agree that apostasy from Islam is a crime that warrants the death penalty. And over the last two decades high-profile Muslims who have come to the West and spoken out against Islam have frequently done so under the threat of death. While we may be justified in distinguishing between Islamic personal piety and the radicalism of contemporary Islamic militants who promote violence, we cannot, at the same time, deny that militant Islamicists find theological justification for their aggression in Qur’anic texts.

According to Christian theology, in notable contrast, God manifests a love that is conspicuously impartial rather than partial and retributive. There follows from this metaphysic of love the notion of “loving one’s enemy,” which is distinctly Christian in character and quite foreign to Islam. This fact would seem to weaken the Muslim scholars’ claim in Part Two of “A Common Word” that “neighbor-love” is central to Islam. Given the actual practice of Islam, the open letter needs far greater qualification of—and attention to—the concept of “neighbor-love.”

While a serious reading of the Qur’an reveals two contrasting attitudes in Islam—violence and tolerance—what needs emphasizing is that the texts advocating the former are far more numerous than those advocating the latter. This fact surely is not lost on many contemporary interpreters of Qur’anic teaching.

Further Obstacles

Another major point of discontinuity between Muslim and Christian beliefs is both theological and anthropological. Islamic theology rejects the notion of original sin as elucidated in the Bible, which teaches that human beings are both dignified and depraved. This dualistic understanding of human nature is significant, because it supports the biblical doctrine of the imago Dei.

The ramifications of this doctrinal difference not only inform the concept of “neighbor-love” but also suggest a profound difference in available resources for the establishment of basic human rights, civil liberties, and religious freedoms. The theocratic framework required by shari’a law, in which religion and statecraft are not distinct, makes poor soil for the development and maturation of the kind of political philosophy and political culture needed to inform and safeguard basic freedoms and religious toleration.

Viewed historically and theologically, Jesus and Mohammad advance radically different construals of the relationship between God and Caesar. Not insignificantly, their two understandings of “the sword” are also very different. This is why, for instance, Jesus enters Jerusalem riding on a donkey, not on a war-horse.

There are also problems of a textual nature in “A Common Word.” First, the Muslim scholars, while reverently citing “the Holy Qur’an,” do not similarly cite “the Holy Bible,” and as mentioned above, they quote only from the Synoptic Gospels of the New Testament and not from other parts of the Bible. Can this be attributed to mere oversight, or to lack of knowledge of the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures, or is it more likely due to their theological outlook? Second, and critically important to the task of exegesis, the Qur’anic texts that the open letter cites in some cases simply do not correlate with their supposed New Testament counterparts.

Irresponsible Silence

Finally, it is unfortunate that the Yale document presumes to speak for all Christendom, as well as for policy-makers, when it asks for “forgiveness” for both the Crusades and the current “war on terrorism.” In so presuming to speak for all Christians, the signatories have reinforced a false stereotype in Muslim thinking toward non-Muslims. At the very least, this issue should have been left open for further discussions with Muslim leaders, at which reciprocal mutual penitence and forgiveness could be shared.

And even if we grant this premise, which itself is questionable, there is also the fact, ignored by the signatories, of the Yale statement’s silence toward egregious and widespread human rights violations committed by militant expressions of Islam worldwide. By this silence, coupled with the presumption to know how best to handle the terrorist dilemma, the Yale Response divorces itself from the deliberations, complexities, and hard work that attend responsible policy and statecraft.

As Patrick Sookhdeo of the Barnabas Fund has rightly observed, the acceptance by some Christians—mainly Westerners—of communal historical guilt reinforces in Muslim thinking the need to “punish” indigenous Christians in Muslim societies for all the sins against Islam supposedly committed by Christians throughout history. Moreover, notes Sookhdeo, the acceptance of corporate guilt by the Yale group will inevitably have detrimental effects on Christians in Muslim-majority societies who even now are suffering for their loyalty to Christ.

It is perplexing to consider how such basic elements and contradictions could be sidestepped by both documents. Given the stated rationale for “A Common Word”—namely, to get Christians and Muslims to work together for peace and justice in the world—shouldn’t these problems be part of an honest interfaith dialogue? Can there be serious dialogue as long as they are ignored?

Fashioning Bona-Fide Dialogue

As one who has been involved in ecumenical dialogue for the last two decades, I have no wish through this essay to throw cold water on any attempts at ecumenical or interfaith exchange—much to the contrary. My particular focus, rather, has been to take two documents that have received considerable fanfare and weigh their particular claims in the light of the evidence. However well-intentioned, both documents ignore fundamental theological and ethical obstacles that impede authentic dialogue, not least of which is the fact that the two faiths assert mutually exclusive claims at the most basic metaphysical level that have weighty ethical consequences. The Yale document in particular, by not inquiring about these fundamental obstacles, leaves the impression that it is a document of appeasement rather than of serious theological and ethical reflection.

At the same time, there does exist considerable common ground between the two religions. One might cite as examples: the notion of verbal and scriptural revelation and authority; the importance of good works; heterosexual marriage as divinely instituted and socially stabilizing, Abrahamic lineage; God as the all-powerful, all-wise, and all-knowing Creator; belief in the angelic and demonic realms; belief in a final day of judgment and moral reckoning; the notion of covenant; and the idea of resurrection and life after death. The two documents, however, do not emphasize these elements. In the end, a sober reading shows them to have highlighted uncommon ground.

Future prospects for dialogue on common ground will need to be rooted in theological integrity rather than circumvention of fundamental differences and contradictions. Christians might best promote authentic dialogue by doing as the Vatican has done—namely, by inviting select Muslim theologians and representatives, in earnest, to discuss theological common ground while not ignoring the plight of persecuted Christian minorities in Muslim cultures that are undergoing great suffering as a result of their confession of—or conversion to—Christianity.

Indeed, Benedict’s address to the Catholic-Muslim Forum in November of 2008 might serve as an exemplar of how this dialogue might proceed. Citing the Golden Rule as the baseline ethical standard for all peoples, and mentioning fundamental human rights no less than four times in his brief address, he admonished his audience:

[Y]our faith will not be perfect, unless you do unto others that which you wish for yourselves. We should thus work together in promoting genuine responsibility for the dignity of the human person and fundamental human rights. . . . My hope, once again, is that these fundamental human rights will be protected for all people everywhere. Political and religious leaders have the duty of ensuring the free exercise of human rights in full respect for each individual’s free exercise of conscience and freedom of religion. The discrimination and violence which . . . today religious people experience throughout the world, and often violent persecutions to which they are subject, represent unacceptable and unjustifiable acts, all the more grave when they are carried out in the name of God.

Benedict, I would suggest, offers the proper model by which to entertain and advance Muslim-Christian dialogue. •

Benedict’s Regensburg address can be found at the Vatican website: www.vatican.va. The texts of the first open letter to the pope, of “A Common Word,” and of the Yale Response can be found at the website .

J. Daryl Charles is the Acton Institute Affiliated Scholar in Theology & Ethics. He is the author or editor of twenty books, including Retrieving the Natural Law (2008), Natural Law and Religious Freedom (2018), and, most recently, Just War and Christian Traditions (forthcoming). He is also co-editor of Abraham Kuyper, Common Grace: God's Gifts for a Fallen World, Volume 3 (2020). He is a contributing editor to Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on islam from the online archives

more from the online archives

31.5—September/October 2018

Errands into the Moral Wilderness

Forms of Christian Family Witness & Renewal by Allan C. Carlson

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor