The Public Bible

The Bible and Its Influence

Cullen Schippe and Chuck Stetson, general editors

Bible Literacy Project, 2006

(387 pages, $67.95, hardcover)

reviewed by C. T. Maier

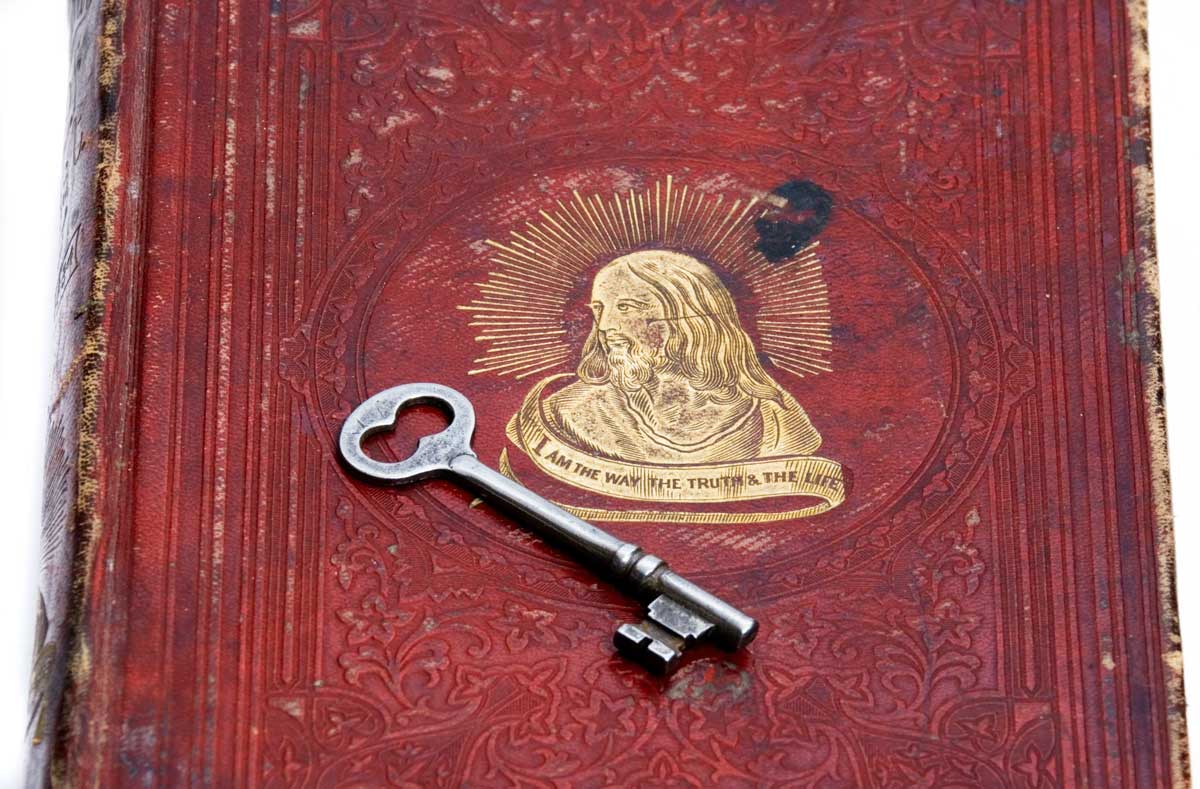

When I was in college, I stumbled across the word shibboleth in an article I was reading. Puzzled, I pulled out my battered Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary and started thumbing through the well-worn pages. If I were a student today, though, I would need to look no further than page 84 of The Bible and Its Influence, the first-ever Bible textbook designed specifically for public high schools, released recently by the Biblical Literacy Project of Fairfax, Virginia.

There, I would learn that the word shibboleth has its roots in the story of Jephthah in the Old Testament. Knowing that his enemies couldn’t pronounce certain Hebrew words, Jephthah asked them to say “shibboleth.” They tripped over the pronunciation, and the word was passed on in language and literature to refer to words and phrases groups use to differentiate members from outsiders.

The phrase “Bible in the classroom” has actually been something of a shibboleth itself. Christian conservatives have advocated Scripture study in the classroom, while religious and secular liberals have done almost everything in their power to resist them. In recent years, supporting the reading of the Bible in public schools has been enough to establish a person’s conservative orthodoxy.

Common Ground

The Bible and Its Influence is the Biblical Literacy Project’s attempt to find a middle way between Christians and those who insist on a radical separation of church and state. Founded in 2001 with the belief that “failure to teach about the Bible leaves students in ignorance and cultural illiteracy,” the group has sought common ground among schools, religious groups, and civil liberties advocates to return Scripture to the classroom.

After a thorough review of First Amendment law, they assembled a roster of forty reviewers from every branch of Christianity and Judaism—including Yale literary critic Harold Bloom, the University of Chicago’s Jean Bethke Elshtain (a Lutheran), Harvard Law School’s Mary Ann Glendon (a Catholic), and Orthodox writer Frederica Mathewes-Green—to create content that would get by the censors.

The resulting textbook is based on the premise that Scripture’s cultural value can be separated from its moral and devotional value. Glossing over polarizing questions like evolutionary theory, it makes the case that the profound influence of the Bible on Western culture, philosophy, language, art, and literature makes it central to even the most basic cultural literacy, for believers and nonbelievers alike.

As the story of the derivation of shibboleth suggests, the emphasis is on the literary and cultural importance of the words, stories, and themes of Scripture. On every page, the book reminds students of the absolute importance of its material. The pervasive need to remind students of the importance of Scripture is, of course, a testament to the times in which we live.

Each chapter offers something new, such as how “cucumber,” “blab,” and “the powers that be” became part of the language when the Bible was translated into English. Or how Shakespeare peppered his plays with over 1,300 biblical references. Or how you can’t understand Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea without understanding its Christological imagery. As they trace the Bible through the history of art, literature, music, and philosophy, students get something that’s essential but also increasingly rare: a broad-based liberal education that embraces the entire scope of Western thought.

Will It Work?

But will it work? Will The Bible and Its Influence bring the Bible, once again, into American public schools? And even if it does find its way into American classrooms, will approaching the Bible for its literary and cultural value alone bear any fruit?

The book assumes that the uneasy separation of church and state can be satisfied by a separation of biblical devotion and biblical content. But the content is too intimately related to the devotion for the Bible to be completely secularized. Even as The Bible and Its Influence tries to take a secular approach, the language of faith still seeps through.

“Modjeska Simkins,” one caption reads, “used both the Old and New Testaments to fight the sin of segregation.” A normal sentence in Christian circles, to be sure, but the passing reference to sin, even when referring in a limited, politically correct way to a thing like segregation, is something altogether different to a secular child who doesn’t believe in sin at all.

The problem—that is, from the secularist point of view—emerges early. In the chapter on Genesis, even as the writers are on their best behavior, Christian belief in things like a purposeful creation, stewardship, and human dignity slip into the narrative. The authors dodge this somewhat by reducing the ordered and purposeful creation to the basis for scientific reason, stewardship to environmentalism, and human dignity to political equality.

But these ideas are not so easily truncated into such politically correct terms, and attempting to do so is likely to offend believers and secularists alike. The belief in a purposeful creator who invests humans with unique dignity and definite responsibilities is one of the most powerful ideas in history. Believers do everything to bring it to light. Secularists do everything to keep it under wraps. No amount of editing will bridge that divide.

Tragic Dance

A content-only Bible textbook does not avoid censorship, but merely censors the Bible in a different, less obvious, way. What happens when ultimate—that is, religious—questions just pop up at the most inconvenient times? One can see students and teachers comically—and tragically—dancing around things they want to talk about but can’t, like characters in a bad sitcom or a Beckett play.

Some may see even the possibility that these questions might be asked in a public school as a sign of hope. How they are answered and who will answer them, though, is uncertain.

C. T. Maier works in the communications office of the Catholic Diocese of Pittsburgh. He attends the First Presbyterian Church of Bakerstown in the North Hills of Pittsburgh. He writes on the intersection of religion and rhetoric.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on bible from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor