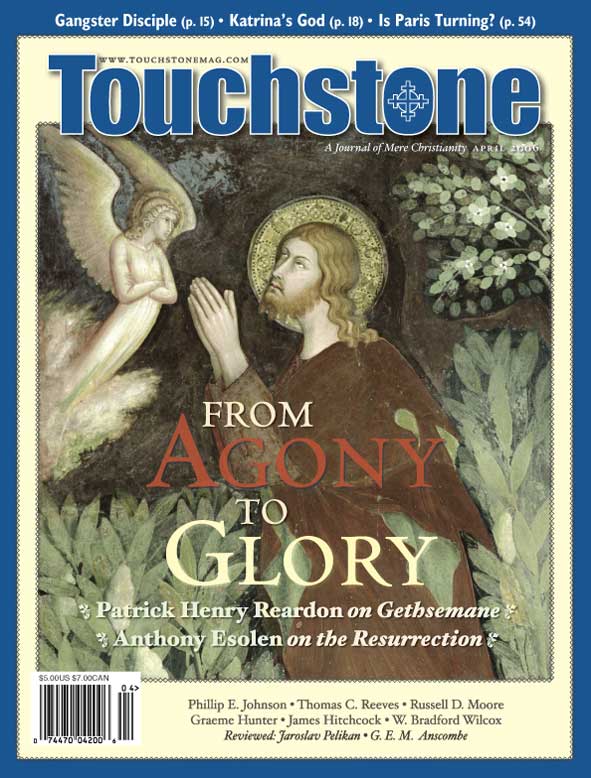

The Agony of Gethsemane

On the Meaning of Christ’s Prayer & His Obedience in the Garden

by Patrick Henry Reardon

Perhaps no part of the Gospel narrative of the Lord’s Passion manifests more dramatically what St. Paul called “the weakness of God” (1 Cor. 1:25) than the account of Jesus’ trial in the garden. Indeed, when the pagan Celsus, late in the second century, wrote the first formal treatise against the Christian faith, he cited that Gospel scene in order to assault the doctrine of Jesus’ divinity: “Why does he shriek and lament and pray to escape the fear of destruction, speaking thus: ‘Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from me’?”

Celsus greatly oversimplified the story of course. Refuting him in the following century, Origen remarked that the Gospels do not claim that Jesus “lamented” ( oduretai) his coming death and that Celsus failed to note that the foregoing prayer of Jesus was immediately followed by the words, “Nevertheless, not my will, but yours be done,” a sentiment demonstrating our Lord’s “piety and greatness of soul,” his “firmness,” and his “willingness to suffer.”

Needless to say, all Christians are at one with Origen’s critique of Celsus on this point, but they should also consider the force of that pagan’s blasphemous attack. Although Celsus’s “malice” ( kakourgon) denied him access to the true meaning of the agony in the garden, that dolorous event at least instructed this unbeliever with respect to Jesus’ full humanity. In fact, Celsus reasoned, Jesus in the garden was so utterly human that he could not possibly have been divine.

Even as we reject that heretical conclusion, we also recognize that the fullness of Jesus’ humanity was most manifest in that event described by the Epistle to the Hebrews as “the days of his flesh” (5:7). In the Lord’s experience in the garden, we perceive the most profound inferences of the doctrine of the Incarnation.

Indeed, this is the very reason that the early Church made no secret of the Lord’s agony in the garden. In all the Gospels except John, Judas’s treachery toward Jesus on “the night in which he was betrayed” (1 Cor. 11:23) is preceded by an account of our Lord’s prayer in the garden, which thus becomes the opening scene of his sufferings.

In the comments that follow, it is my purpose to examine these Gospel accounts, along with the parallel narrative in the Epistle to the Hebrews, in order to reflect theologically on the significance of the trial and prayer of Jesus in the garden and the special, mysterious place that Holy Scripture recognizes in that event in the accomplishment of our redemption.

The Mystery of Sadness

Interpreting the death and resurrection of Jesus in the light of biblical literature (cf. 1 Cor. 15:3–4), the early Christians savored the contrast between the disobedience of Adam and the obedience of Christ. They perceived that whereas the first man attempted, in rebellion, to become God’s equal, the second, “being in the form of God, did not regard being equal to God a usurpation [ harpagmos], but he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being made in the likeness of men, and being found in shape as a man, he humbled himself, becoming obedient unto death” (Phil. 2:6–8, my translation).

In the Epistle to the Romans, the Apostle Paul further elaborated the disparity between Adam and Jesus, observing that, “as by one man’s disobedience many were made sinners, so also by one Man’s obedience many will be made righteous” (5:19).

It is very important to bear in mind the traditional contrast of the obedient Jesus with the disobedient Adam when we come to the Gospel accounts of our Lord’s struggle at Gethsemane, the place of his betrayal. The very name of this place (Mark 14:32; Matt. 26:36) means “olive garden,” abbreviated to simply “a garden” by John (18:1).

This garden of Jesus’ trial was, first of all, a place of sadness, the sorrow of death itself. “My soul is exceedingly sorrowful,” said he, “even unto death” (Mark 14:34; Matt. 26:38). This sorrow unto death is common to the two gardens of man’s trial, the garden of Adam and the garden of Jesus.

In the garden of disobedience, the Lord spoke to Adam of his coming death, whereby he would return to the dust from which he was taken. That curse introduced man’s sadness unto death. Thus, in the Septuagint version of this story the Lord tells Eve, “I will greatly multiply your sorrows ( lypas),” and “in sorrows ( en lypais) you will bear your children.” And to her husband the Lord declares, “Cursed is the ground for your sake; in sorrows ( en lypais) you shall eat of it all the days of your life” (Gen. 3:16,17,19).

It is common to think of our Lord’s prayer in the garden in reference to his fear, but it is significant that the accounts in Matthew and Mark emphasize his sadness more than his fear. Jesus said in the garden, “My soul is exceedingly sorrowful ( perilypos), even unto death.” The context of this assertion indicates that Jesus assumed the primeval curse of our sorrow unto death, in order to reverse the disobedience of Adam. In the garden, Jesus took our grief upon himself, praying “with vehement cries and tears” (Heb. 5:7). In the garden he bore our sadness unto death, becoming the “Man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief” (Is. 53:3,4).

Thus, St. Ambrose of Milan, commenting on the agony in the garden, says of Jesus: “Nowhere do I wonder more at his piety and majesty, because it would have profited me less if he had not assumed my own feelings ( nisi meum suscepisset affectum). Therefore, the One that had no reason to sorrow for himself sorrowed for me, and leaving aside the enjoyment of his eternal divinity, he is afflicted with the weariness of my infirmity. He assumed my sadness ( suscepit tristitiam meam), in order to confer on me his joy, and in our footsteps he descended even to the sorrow of death ( ad mortis aerumnam), in order to recall us to life in his own footsteps.”

In the garden Jesus returns to the very place of Adam’s fall, taking on himself Adam’s sorrow unto death. Thus, Ambrose regards Christ’s assumption of man’s sadness in the garden as integral to the Incarnation itself. He comments, “Therefore, I confidently use the word ‘sadness,’ because I preach the Cross, because he did not assume the appearance of the Incarnation, but its truth. Consequently, he had to take on grief ( dolorem suscipere), in order to overcome sadness ( tristitiam), not to exclude it. The praise of fortitude does not belong to those who bear the numbness, but rather the pain, of wounds.”

The commiserating Christ bears in the garden, then, the very sorrow incurred by fallen mankind. In this garden scene St. Cyril of Alexandria places on the lips of Jesus the following explanation of his grief: “What vinedresser, when his vineyard is desolate and laid waste, will feel no anguish for it? What shepherd would be so harsh and stern as to suffer nothing on account of his perishing flock? These are the causes of my grief. For these things am I sorrowful.”

The Mystery of Prayer

Besides the accounts in the Synoptic Gospels, the Epistle to the Hebrews also refers to the Lord’s prayer in the garden. It is there that we read of Jesus, “who, in the days of his flesh, when he had offered up prayers and supplications, with vehement cries and tears to him who was able to save him from death, and was heard because of his godly fear, though he were a Son, yet he learned obedience by the things which he suffered” (5:7–8).

In this precious text, the reference to “vehement cries and tears” explains how the early believers knew about this event. It was among those things, as the author says, “confirmed to us by those who heard him” (2:3). The first apostles were immediate witnesses to the event, some of them only “a little farther” off (Matt. 26:39), “about a stone’s throw” (Luke 22:41). These disciples could hear those “vehement cries,” and they were able to see his kneeling posture (Mark 14:35).

All this happened, says Hebrews, “in the days of his flesh,” an expression indicating Jesus’ condition of human weakness, willingly assumed so “that through death he might destroy him who had the power of death, that is, the devil” (Heb. 2:14).

The object of Jesus’ “prayers and supplications,” Hebrews tells us, was deliverance from death. This feature of his prayers corresponds to the Gospel accounts in which Jesus prays that he be spared the “cup” of his coming sufferings (Matt. 26:39,42) and that “the hour might pass from him” (Mark 14:35).

It was in this hour, says Hebrews, that Jesus “learned obedience by the things which he suffered,” a parallel to the Gospel accounts in which Jesus, in his agony, submits his own will obediently to that of his Father (Matt. 26:39,42; Mark 14:36; Luke 22:42). As we have seen, the Apostle Paul preserves part of a hymn that speaks of Jesus’ obedience unto death, “even the death of the cross” (Phil. 2:8).

These prayers and supplications of Jesus are themselves sacrificial, because Hebrews says that he “offered” them ( prosenegkas). They are priestly prayers. That is to say, Jesus’ sacrifice has even now begun. The Lord’s Passion is a seamless whole. Already we perceive in his prayers and supplications the true essence of sacrifice, which is the inner oblation of oneself to God.

The Book of Hebrews insists, furthermore, that these “prayers and supplications” of Jesus were heard on high, precisely because of “his godly fear,” which is to say, his godly piety and reverence ( evlabeia; reverentia in the Vulgate). Jesus’ obedient reverence is exactly what we find in the Gospel accounts of the agony.

In what sense, then, was Jesus “heard” when he offered these prayers and supplications? Properly to answer this question, it is useful to remember a principle of all godly petition: “Now this is the confidence that we have in him, that if we ask anything according to his will, he hears us” (1 John 5:14). Jesus prayed explicitly according to God’s will; indeed, it was the very essence of his prayer. Therefore, his prayer was heard according to God’s will. He was not delivered from death in the sense that he avoided it, but in the sense that he conquered it, that he was victorious over death, that in his own death he trampled down death forever.

This is to say that Jesus’ resurrection and glorification were the Father’s response to his prayer in the agony. It was in answer to his prayer, “Thy will be done,” that Jesus, “having been perfected . . . became the author of eternal salvation to all who obey him” (Hebrews 5:9). This was God’s will, the will that Jesus prayed would be done. He was thus “made perfect through sufferings” (2:10). It was because Jesus became obedient unto death that “God also has highly exalted him” (Phil. 2:9). The Paschal victory over death was the Father’s reply to the prayers and supplications offered by the true High Priest in the days of his flesh.

Prayer & the Will of God

From these reflections it is clear that our Lord’s prayer at Gethsemane illustrates the mystery of prayer itself. This illustration is worthy of further comment.

Times out of mind we have been told by some sincere Christians that the promise given by Jesus—the promise that his Father will grant us whatsoever we ask in his name (John 16:23–24)—is absolute and “allows of no exceptions.” I have even heard some Christians, citing this text, go on to remark that even the addition of “if it is thy will” bespeaks a want of sufficient faith, inasmuch as it suggests that the person making the prayer is failing in confidence that his prayer will be answered. That is to say, a prayer containing an “if,” because it is ipso facto hypothetical, expresses an inadequate faith. What the believer should do, I have been told, is simply “name it and claim it.”

What the Bible has to say about petitionary prayer, however, is contained in many biblical verses, all of them worthy of careful regard. For example, should we say that the Apostle Paul, when he prayed three times that the Lord would remove from him the thorn in his flesh, the angel of Satan sent to buffet him (2 Cor. 12:8), was wanting in faith because this severe affliction was not taken away?

If this was the case—if the Apostle to the Gentiles really was so deficient in personal faith—it is no wonder that he was obliged to leave Trophimus sick at Miletus (2 Tim. 4:20). Poor ailing Trophimus, languishing there on his sickbed; he should have been prayed over by a person with a sounder, fuller, more unfailing faith, not that slacker Paul, a man apparently deficient on the subject of faith.

The truth of the subject, however, is quite different. The addition, “if it is thy will,” is neither a limitation imposed on our confidence nor a restriction laid on our prayer. It expresses, rather, a constitutive feature of true prayer and an essential component of faith. The real purpose of prayer, after all, is not to inform God what we want, much less to impose our will on him, but to hand ourselves over more completely, in faith, to what God wants. The purpose of prayer, even the prayer of petition, is living communion with God. The man who tells God, then, “Thy will be done,” does not thereby show himself a weaker believer but a stronger one.

After all, was Jesus, “the author and perfecter of our faith,” weak in faith when he added the “Thy will be done” to the petition “Take this cup from me”? Did he not, rather, give us in this form of his petition the very essence of true prayer?

“If it is thy will,” then, is not a limit on our trust, but an expansion of it. It does not denote a restriction of our confidence but an elevation of it. It is an elevation because in such a prayer—“Thy will be done”—we grow in personal trust in the One who has deigned, in his love, to become our Father. Indeed, when Jesus makes this prayer in the garden, the evangelists are careful to note exactly how he addressed God—namely, as “Father.” Indeed, they even preserve the more intimate Semitic form, “Abba.”

The “will of God” in which we place the trust of our petition is not a blind, arbitrary, or predetermined will. It is, rather, the will of a Father whose sole motive (if this word be allowed) in hearing our prayer is to provide loving direction and protection to his children. “According to thy will” is spoken to a Father who loves us because in Christ we have become his children.

All of this theology was contained in Jesus’ prayer in the garden, by which his own human will was united with the will of God. Jesus, in praying for the doing of God’s will, modeled for us the petition contained in the prayer that he gave us in the Sermon on the Mount. This prayer, which significantly begins with “Our Father,” goes on to plead that his will may be done.

Obedience & Authority

We earlier reflected that in the Lord’s agony, we perceive the most profound inferences of the doctrine of the Incarnation, the enfleshing of God’s eternal Son.

Jesus in the garden subjected to the Father, not only the assent of his will, but also the disposition of his flesh. In this regard, the author of Hebrews places on the lips of the Son, “when he came into the world,” the words of the psalmist, “Sacrifice and offering you did not desire, But a body you have prepared for me./ In burnt offerings and sacrifices for sin you had no pleasure./ Then I said, ‘Behold, I have come—in the volume of the book it is written of me—to do your will, O God’” (10:5–7; Psalm 40 [39]:6–8).

“A body you have prepared for me,” says the incarnate Word to his Father. We may contrast this to the Hebrew text of Psalm 40:6, which reads, “Sacrifice and offering you did not desire; my ears you have opened.” Perhaps relying on the Septuagint (as reflected in its three earliest extant manuscripts), the author of Hebrews changes “ears” to “body.” He thereby asserts that Jesus in his very body, and not simply in the assent of his will, accomplished our redemption.

This assertion must not be disregarded, lest we fall into serious doctrinal error. It has sometimes been alleged that our redemption was really wrought, not on Golgotha, but in Gethsemane, when Jesus explicitly submitted his will in obedience to the will of the Father. Some Eastern theologians, in particular, overreacting to a Western juridical soteriology, attempted to spiritualize redemption, even to moralize it. They advanced the theory that Jesus purchased our redemption, not by the immolation of his body on the Cross, but by his internal, spiritual sufferings in the garden.

According to this view, redemption was essentially accomplished by the obedient human will’s deliberate submission to the divine will. Indeed, some have attempted to bolster this thesis through the biblical assertion that the true sacrifice acceptable to God consists in an internal immolation of the heart (Psalm 51 [50]:16–17).

This exaggerated theory, it must be said, does not correspond to biblical soteriology, according to which “we have been sanctified through the offering of the body of Jesus Christ” (Heb. 10:10). A full Christian view of redemption will insist that it happens in the body. To separate the suffering and death of Christ in the body from the internal obedience of his will to the Father does violence to the Holy Scriptures. Indeed, it does violence to the Incarnation itself, whereby “he himself likewise shared in [flesh and blood] that through death he might destroy him who had the power of death, that is, the devil” (2:14).

The submission of Jesus’ will led directly to the immolation of his body and the libation of his blood. His agony in the garden pertains, thus, to a single purpose, extending from his assumption of our flesh all the way to its ascent, finally, into heaven. The Church knows of no redemption apart from what God’s Son accomplished in the flesh.

The Physician’s Perspective

When we speak of our Lord’s “agony” ( agonia) to describe his prayer in the garden, we are borrowing the expression from St. Luke (22:44), the only New Testament writer to use this word. There are two other distinctive features in Luke’s version of this event.

First, Luke omits the threefold form of Jesus’ prayer found in Mark and Matthew. His version, therefore, is shorter.

Second, the traditional form of the Lukan text contains certain details not found in the other two Synoptics. To wit, “Then an angel appeared to him from heaven, strengthening him. And being in agony, he prayed more earnestly. Then his sweat became like great drops of blood falling down to the ground” (Luke 22:43–44). These particulars about the bloody sweat and the comforting angel we know only from Luke.

Because the older, reputedly more reliable manuscripts of Luke do not contain these verses, some scholars argue that they were not part of the “original form” of Luke. For two reasons, nonetheless, I believe this judgment is too hasty.

First, given the considerable textual differences among the Lukan manuscript traditions (in the Last Supper story, for instance), I am not convinced there really was a single “original form” of Luke’s Gospel. It seems to me not unreasonable to suspect that Luke himself may have left it to us in more than one form. (This consideration, let me add, seems applicable to other New Testament authors as well. Since many writers produce more than one version of their works, why would this be off-limits to the divinely inspired writers?)

Second, this impression of more than one original Lukan text is strengthened by the fact that the passage in question (Luke 22:43–44), though not found in the earliest manuscripts, was very well known from the earliest times. In truth, these Lukan features appear so soon after his Gospel’s composition that it seems downright rash to claim they were not part of the “original” text.

For instance, about halfway through the second century, St. Justin Martyr wrote: “According to the Memoirs [ apomnemonevmata, Justin’s common expression for the Gospels], which I say were composed by the Apostles and their followers, his sweat fell down like drops of blood while he was praying.”

This citation, as old as any extant manuscript of Luke, shows that Justin was familiar with the disputed verses. Shortly after Justin, moreover, St. Irenaeus of Lyons also wrote of the bloody sweat, as did Hippolytus of Rome, who mentioned, as well, the angel who strengthened Jesus. Later, Epiphanius of Cyprus and others followed suit.

Bloody Obedience

For these reasons, and because this passage has long been received in the Church as integral to the Lukan text, my comments on these verses will presume Luke’s authorship of them. Let us consider more closely, then, the Lord’s bloody sweat and the angel who strengthened him.

First, there is the sweat of blood, a condition called hematidrosis, which results from an extreme dilation of the subcutaneous capillaries, causing them to burst through the sweat glands. This symptom, mentioned as early as Aristotle, is well known to the history of medicine, which sometimes associates it with intense fear. It is not without interest, surely, that only the evangelist who was also a physician mentions this phenomenon.

Unlike Mark (14:34) and Matthew (26:38), Luke does not speak of Jesus’ sadness in the garden scene, but of an inner struggle, an agonia, in which the Lord “prayed more earnestly.” The theological significance of this feature in Luke is that Jesus’ internal conflict causes the first bloodshed in the Passion. His complete obedience to the Father in his prayer immediately produces this initial libation of his redemptive blood, the blood of which he had proclaimed just shortly before, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is shed for you” (Luke 22:20).

Prior to the appearance of his betrayer, then, the Lord already begins the shedding of his blood. He pours it out in the struggle of obedience, before a single hand has been laid upon him. In Luke, the agony in the garden is not a prelude to the Passion, but its very commencement, because Jesus’ stern determination to accomplish the Father’s will causes his blood to flow for our redemption.

Second, there is the angel sent to strengthen the Lord during his trial. Luke, in his earlier temptation scene, had omitted the angelic ministry, of which Matthew (4:11) and Mark (1:13) spoke on that occasion. When Luke did describe that period of temptation, however, he remarked that the devil, having failed to bring about Jesus’ downfall, “departed from him until an opportune time” (4:13). Now, in the garden, that time has come, and Jesus receives the ministry of an angel to strengthen him for the task.

This is one of those angels of which Jesus asks Peter in the Gospel of Matthew: “Or do you think that I cannot now pray to my Father, and he will provide me with more than twelve legions of angels?” (26:53) This angelic ministry was ever available to him, but now Jesus is in special need of it.

In Luke’s literary structure, this ministering angel stands parallel to Gabriel at the beginning of the Gospel. In the earlier case, an angel introduces the Incarnation; in the present case, an angel introduces the Passion. Very shortly, angels will introduce the Resurrection (24:4). •

The non-Scriptural references are, in order, to: Origen, Contra Celsum 2.24; Ambrose, Homiliae in Lucam 10.56; Cyril of Alexandria, Homiliae in Lucam 146; Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 103.8; Irenaeus, Adversus Haereses 3.22.2; Hippolytus, Fragments on Psalms 1 [2.7]; Epiphanius, Ancoratus 31:4–5; and Aristotle, Historia Animalium 3.19.

Patrick Henry Reardon is pastor emeritus of All Saints Antiochian Orthodox Church in Chicago, Illinois, and the author of numerous books, including, most recently, Out of Step with God: Orthodox Christian Reflections on the Book of Numbers (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2019).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on bible from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor