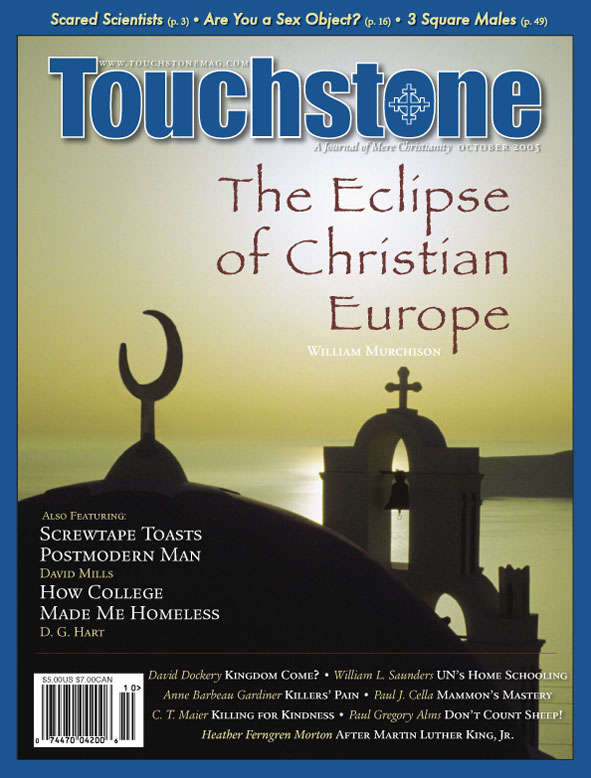

Vanishing Sea of Faith

European Islam & the Doubtful Future of Christian Europe

by William Murchison

I know we know all this. We used to at least. I do confess to hearing in church these days fewer rousing renditions of “Onward Christian Soldiers” than during my 1950s adolescence. Well, you know, all that military stuff: soldiers, mighty armies, not to mention “brothers” advertised as “treading” out in front, certainly, of their sisters. Scandalous! Outmoded! In the minds of the modern Christian establishment, anyway.

Which may be just the problem as the mighty army that once constituted Christianity pulls up short before the awful sight of . . . indifference and apathy, or perhaps cultivated hostility. The banners droop. Looks of puzzlement cross earnest faces. No one . . . cares anymore?

What could that mean? Nothing good, that’s for sure.

Christianity Unwanted

The plight of Christianity in Europe, if not yet in America, has become the topic of the moment in religious as well as secular circles, and the modern Christian establishment professes bewilderment. What goes on? No one wants the product the churches profess to be selling? In statistical, as well as anecdotal terms, that would appear to be the case. Consider:

• Just 21 percent of Europeans (according to a recent European Values Study) call religion of any kind “very important.” Only 15 percent worship even once a week.

• On average, only 41 percent of Europeans claim belief in a personal God. In Britain the percentage of believers has fallen from 77 percent in 1968 to 44 percent today. That’s “believers,” as opposed to the distinctly smaller class of believer-practitioners who on Sundays put their posteriors where their minds are. The number of Muslims at Friday prayers in Britain reportedly exceeds the number of Anglicans at Sunday worship. A recent Wall Street Journal article referred to Tony Blair as “the Christian leader of a pagan country.”

• In Ireland—Ireland!—just half the population reportedly goes to Mass now, compared with 84 percent in the early 1990s. To quote one bored boyo, a web designer by trade, “It’s the repetition. After you’ve heard it enough, you feel like you already know what they’re going to say, so why do you have to go there?” Yes, why, Brendan, Brigid, Patrick?—the whole lot of you who saw participation in Christ’s sacrifice as the holiest of privileges.

• The European Union in 2004 notoriously declined entreaties from religious leaders to include in its 70,000-word constitution some acknowledgement of the continent’s Christian heritage.

• Spain’s socialist government—Spain’s!—legitimized same-sex “marriages.”

• The papal biographer George Weigel, who has lately written a deft little book on the subject, The Cube and the Cathedral, sees a continent gripped by “metaphysical boredom,” its high culture actually “Christophobic” in content. “European man,” Weigel asserts, “has convinced himself that in order to be modern and free, he must be radically secular.”

• The new pope, Benedict XVI, previously Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, who inherits the job of addressing all this confusion of purpose, would surely agree with Weigel’s analysis. Benedict views as “total profanity” the “ideological secularism” that is seemingly now Europe’s overarching creed.

Milton, thou shouldst be living at this hour! And maybe, for good measure, Luther, Calvin, Augustine, Aquinas, and C. S. Lewis. Not excluding Hilaire Belloc, who at the end of World War I saw all this coming: the “dissolution of standards,” the “melting of the spiritual framework.”

In Europe and the Faith, Belloc wrote glumly of how “authority, the very principle of life, loses its meaning, and this awful edifice of civilization which we have inherited . . . trembles and threatens to crash down.” Then the closing, well-remembered grace note: “Europe will return to the Faith, or she will perish. The Faith is Europe. And Europe is the Faith.”

Crescent Europe

Read a certain way, Belloc’s warning calms and soothes. All this was 85 years ago—eight and a half decades. Nor did the Faith, in this time span, really recede from view. Maybe it won’t now.

You could put the matter that way, yes. Yet spinning will not conceal European Christianity’s undoubted perplexities and hardships. In recent decades another perplexity has arisen: that of a large and increasingly aggressive Muslim population, especially in France, Germany, Britain, and the Netherlands.

The July 7 outrages in London exploded literally in the face of a society hoping, with fingers crossed, to accommodate Islamic culture, only to discover that native-born adherents to that culture were unwilling to accommodate the accommodationists. As the Daily Telegraph noted a week or so after the bombings, “There is within the Muslim community in Britain a disaffected, radicalised group of young men who listen, almost daily, to rabble-rousers preaching the message of holy war.”

The historically minded—excluding a large number of public education’s most recent products—will recall how relatively few years it has been since Muslim armies and navies were trying to bring Christian Europe under the star and crescent. What repelled them, at Lepanto and at the outskirts of Vienna? Military might, marshaled by the conviction that Europe, being Christian, had to remain so. There was something then to fight for.

What is there now? The European constitution, with its silence concerning the Faith? The 35-hour workweek? Pensions? Soccer? Rock concerts? Homosexual “marriage” and all those alternative sexual practices unavailable (at least in public) in Islamic countries?

Yes, and what happens when Muslim immigrants refuse secular identity with their new homelands? When, for instance, as happened recently, a Dutch Muslim murders in broad daylight a prominent, indeed obstreperous, critic of Islam? The Muslim who sees himself as a Muslim first and a Dutchman second or third or fourth—to the extent he sees himself as affiliated in any urgent way with a secular nation and people—is clearly not playing by the secular rules of secular Europe.

Those rules specify tolerance for diverse viewpoints as crucial to modern citizenship. The secular European easily accedes to this viewpoint. Not so the newcomer who asserts the hard, burning faith of the desert in preference to the kind thoughts and good wishes of the housing development.

Drawing on the fate of Byzantium nearly 700 years ago, Weigel proposes in The Cube and the Cathedral the once-unimaginable scenario of a Europe overwhelmed by its ancient adversaries: “The muezzin summons the faithful to prayer from the central loggia of St. Peter’s in Rome, while Notre-Dame has been transformed into Hagia Sophia on the Seine—a great Christian church become an Islamic museum.”

Hmmm, that might finally get Jacques Chirac’s attention—not least on account of the probable effects on American tourism. (How many Methodists from Gopher Prairie want to visit a mosque?) I think, though, that what gives Weigel’s scenario most of its power is contextual—as no doubt he intended. What indeed would it mean for Notre-Dame to become Hagia Sophia on the Seine? The victory of Mohammed over Christ is what it would mean; the Incarnate Son of God displaced by the desert seer with the multiple wives.

Swept Away

That should give us pause. Centuries of Christian belief swept away in a great cosmic sorting-out; history stood on its head. A wispy fantasy after all, these tales of a holy man with power to transform loaves and fishes; a faith worthy in intention but empty inside. No God-Man, then; no worshipful wise men or empty tomb, no Holy Ghost, no forgiveness of sins, no coming again in glory; only the wind from the desert penetrating the deepest places of consciousness, sweeping away—never to return—the delusions and distractions of 2,000 years. Gone, all gone!

The death of the old pope and the ascent of a new one invite us to think on these things in ways we may not have for a long time. I want, in response, to pose two questions: (1) Why? and (2) What then?

“Why?” is the tough one. If Europe is the Faith and the Faith is Europe, this thing—this ongoing eclipse of Christianity in Europe—shouldn’t be possible. Except that we look the thing right in the eye and glimpse its painful possibilities. Hagia Sophia on the Seine. Why?

“Why not?” is one way of answering. If you don’t believe a thing is true, or vital, or relevant, in due course you quit acting as though you did, notwithstanding any sentimental attachment you might have to the outward forms and symbols of the old belief structure. Soon enough, when it becomes plain that the Texas Rangers and the World Series may forever remain strangers, you adjust your expectations. You look elsewhere for satisfaction. Europe has long been looking elsewhere for the satisfactions Christianity once supplied.

What do we suppose has been going on there anyway these past couple of centuries—a heart-clutching, hand-clapping revival of Wesleyan proportions? Not a bit of it. What’s been going on is Marxism, Freudianism, and Darwinism. The three dominant intellectual movements of the past two centuries, far from reinforcing Christianity, have pitied, confronted, or persecuted it—in the name of Man: his itches, his intuitions, his lusts.

Nothing—nothing whatever—happens overnight. Historical processes take time. Don’t we recall Matthew Arnold’s mid-Victorian account of the Sea of Faith and its “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar”? Proper Victorianism, and the brilliance of Newman and his school, covered the retreat for a while. On it went anyway, decade after decade: unarrestable by the eloquence of Chesterton and Lewis or the simple piety of the royal family (pre-Charles and Diana).

The Enlightenment of the eighteenth century, building on the disillusionments and fractionations associated with watching Christians burn and hack apart fellow Christians, itself declared war on l’infame (Voltaire’s name for that which inspired Belloc). The French Revolution was one notable consequence. Whenever the mullahs do take over Notre Dame, if they do, they will discover there the tracks of the Goddess of Reason, to whom, in the person of a dancer, the revolutionaries turned over symbolically the sacred old Christian precincts. It has been that kind of era.

Dry-Rotted Europe

And it goes on. In 1871, French radicals shot or hacked to death numerous clergy, including Paris’s archbishop.

During Spain’s civil war, 6,800 priests, monks, and nuns fell to firing squads. The Bolsheviks and the Cheka were tougher still on the spokesmen for Holy Russia. None of this quite qualifies as spirited affirmation of the Christian creeds.

Weigel is right, I think, to note that the dry rot had set in before 1914—the “Nietzschean will to power; a distorted sense of honor; intense nationalism compounded by imperialism; the breakdown of the system of trust” on which diplomacy relied. On and on. Then the second war, with its previously unexampled horrors, with Christian Germany—the Germany of Bach and Luther (not to mention the Ratzingers)—as principal perpetrator.

What does this do for Christian morale, so to call it, and for any inducements Christianity might offer the unconverted?

Meantime, it seems necessary to advise against Americans’ giving themselves pious airs. Ours is a culture that puts more trust in supernatural religion than does Europe’s—but not that much more. On the way to church, my wife and I sometimes joke about the comings and goings on the road: joggers, bicyclists, the lounging crowds at Starbucks. Guess they’re getting a quick refill for the ride to First Methodist, we might say with a wink, well knowing the patrons to be occupied with latte and laptops rather than Bibles.

The legacy of the Enlightenment weighs upon us, as upon our European co-religionists: religion as claptrap and show, churches and cathedrals as places you repair not for physical and spiritual connection to Reality itself but for the satisfaction of habits or social needs or goodness knows what else. Anyway, how to present Christian realities in the context of a culture wedded to choice, change, and the satisfaction of personal wants? The immediate satisfaction, I should add: not deferred to some Better Time. Now. And preferably with as little pain and inconvenience as possible.

Christianity—we should admit it—is un-modern. Or, rather, it is modern in the sense that it encompasses all eras: past, present, and future. What we might call the “modern spirit” is in fact detached from the Christian spirit.

The Promise

And so we come to my second question: What then?

We don’t quite know the answer. We know the promise, nonetheless. It is more bracing by far than anything we see around us. “The gates of hell shall not prevail . . .”! “At the sign of triumph Satan’s host doth flee . . .”!

All this needs looking at with vast seriousness, for two distinct yet closely related reasons.

The first is a strong suggestion in the Lord’s words that what’s wanted from the Church of God, in its relationship to the world, is stark clarity, and a certain boldness. What kind of religious enterprise are a bunch of fishermen likely to get going in the Greco-Roman world, lacking some confidence in the ultimate triumph of Jesus Christ the Messiah over Jupiter and Apollo and Venus and the whole marble-visaged crew positioned atop the physical and metaphysical heights of that world?

Yes, where was this Christ business going? Couldn’t it cause trouble—such as getting you nailed head-down to a cross or treated to other imperial inducements to religious quietism? What was this, though? The gates of hell would not prevail against you. You might just have a fighting chance. Indeed, given the authority with which these memorable words were delivered—though the voice must have been characteristically even in tone—you might have a sure thing. Not painless—sure and certain (as the old Anglican burial service would have it). That would make up for a great deal, it seems easy enough to say with proper distance from all the uproar.

If anything could be said of the Church in the ensuing years and decades and centuries, it was that the Church spoke and acted boldly—with divine recklessness, even. Why? Because so it was commanded. The same Gospel that relays to us the news of Peter’s commission moves the matter briskly along, some chapters later: “Go ye therefore and teach all nations.”

What the Church said, essentially, over and over again, to whomever might be listening, was: “You need this. Upon it depends everything. Life, death, everything.” What came more naturally, in this event, than invocations that have not even now lost the capacity to inspire? “Onward Christian soldiers, marching as to war, with the Cross of Jesus, going on before. . . .”

It is the kind of approach we have come to think of, in the twenty-first century, as “intolerant” and “exclusivist.” Only a minor part of the reason for Islam’s rise in Western Europe has to do with the large-scale immigration of Algerians, Turks, and so on, and their subsequent non-amalgamation into the general population. The larger point is that the Muslims who came and began to populate the continent with their own kind found there a steadily enlarging spiritual vacuum.

The cathedrals and churches were open for business, yes; but it was tourists who more and more filled them, and not in a spirit of worship either. More like a mood of dutiful curiosity. An increasingly secular Europe has for decades seen Islam not as an oppositional force in cultural and spiritual terms, but, rather, as one more mode of expression: all the more deserving of tolerance, possibly, on account of onetime Christian proclivities for butting in with the gospel, wherever and whenever.

Ecumenical Enemies

A Europe that saw Christianity as vital in the old terms might admit job-seeking non-Christians to citizenship or residence. That same Europe, nonetheless, would insist on the cultural predominance of Christianity: no heartfelt apologies to non-Christians for the wide and intensive practice of Christianity at home. If Christianity was true, why apologize?

To accord other faiths a status comparable to Christianity’s, you need not only to esteem the ideal of tolerance; you need also to assume that no religious faith makes more than ordinary sense—neither Christianity, nor Islam, nor anything else. In this moral void, take your pick of salvational instruments: the Way of the Cross, the Pillars of Islam, the Euro. Each to his own: a high-minded way of saying, “Who cares, anyway?”

Not that supposedly acute European thinkers, like their American counterparts, lack preferences of their own. These preferences normally turn out to be secular, this-worldly, distrustful of notions rooted in long-past events in far-distant countries: hegiras, virgin births, resurrections, and the like. Christians and Muslims, for all their theoretical antagonism toward each other, have something in common besides monotheism. Secularists don’t know what to do with them.

When the Chirac government in France, seeking better integration of Muslims into the larger community, prohibited students from wearing Islamic headscarves to school, the government thought it necessary to prohibit at school the display of all religious symbols, including the cross. It is worthy of remark that on moral questions such as homosexual rights, a favorite concern of Western secularists, Christians and non-Islamist Muslims sometimes occupy the same moral ground, opposing secular attempts to override traditional moral understandings, based as they are on the sovereign design of God.

A Cheering Alarm

The second, and final, point I would make regarding this gates-of-hell business is withal more cheerful: not quite “What, me worry?”, but not particularly distant from that sentiment either. We find in Christ’s words a rather alarming promise—alarming to adversaries of the Faith.

It is that nothing they can do will polish off his church. Nothing. That would include, I imagine, multi-cultural instruction in schools, prohibitions of religious symbols, the extirpation of Christmas festivities on public property, even the forced emptying of the churches themselves. Persecution, nakedness, and the sword will likewise fail. Martin Luther turned the same perception to account: “The prince of darkness grim, we tremble not for him . . . For, lo, his doom is sure.” I think I am right in declaring this to be the consistent witness of the Church, in all times, all places.

Now we know the impossibility of proving this expectation in terms gratifying to secularists (as well as to some modernity-obsessed “Christians”). But, then, no one can “prove” in secular terms any of the other claims of the Christian faith: baptism for the remission of sins, the resurrection of the dead, the life of the world to come.

If the pledge to Peter, the pledge of the Faith’s unconquerability, has lost resonance, it might be time to plan one last journey to Paris, for one last lingering look at Notre-Dame’s Rose Window, innocent yet of Koranic curlicues.

And if, on the other hand, all is true—as promised at the start; as lived for, fought for, died for during centuries of struggle and splendor—why, one then might just ask, with a certain insouciance, what’s the problem here anyway?

William Murchison a syndicated columnist, is author of Mortal Follies: Episcopalians and the Crisis of Mainline Christianity (Encounter Books).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on islam from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor