Rays of Fatherhood Shining Forth

Why We Call God “Father”: Biblical & Cultural Considerations

Among the many changes sweeping over the world in this century, few are as fraught with cultural and spiritual significance as the changes occurring in our god-language. After a forty-year war against calling God “Father,” waged by feminist theologians in the name of gender equality, male gender language for God, once taken for granted, is now avoided or rejected by growing numbers of people inside and outside the churches.1 God is increasingly referred to simply as “God.” For some, the word God itself is taboo. In a recent book, a leading feminist theologian, Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza, warns of the “male-dominant, misogynist, homophobic, racist and supremacist values” she believes are the inevitable consequence of calling God “Father” and places an asterisk instead of the o at the center of the word God to remind us of “the brokenness and inadequacy” of all human god-language.2 As an alternative she advocates “sophialogy,” a speaking of and about Divine Wisdom, referred to as our companion in our struggles against injustice, just as “she” (spelled “s/he”) was with “the Israelites on their desert journey from slavery to freedom.”3

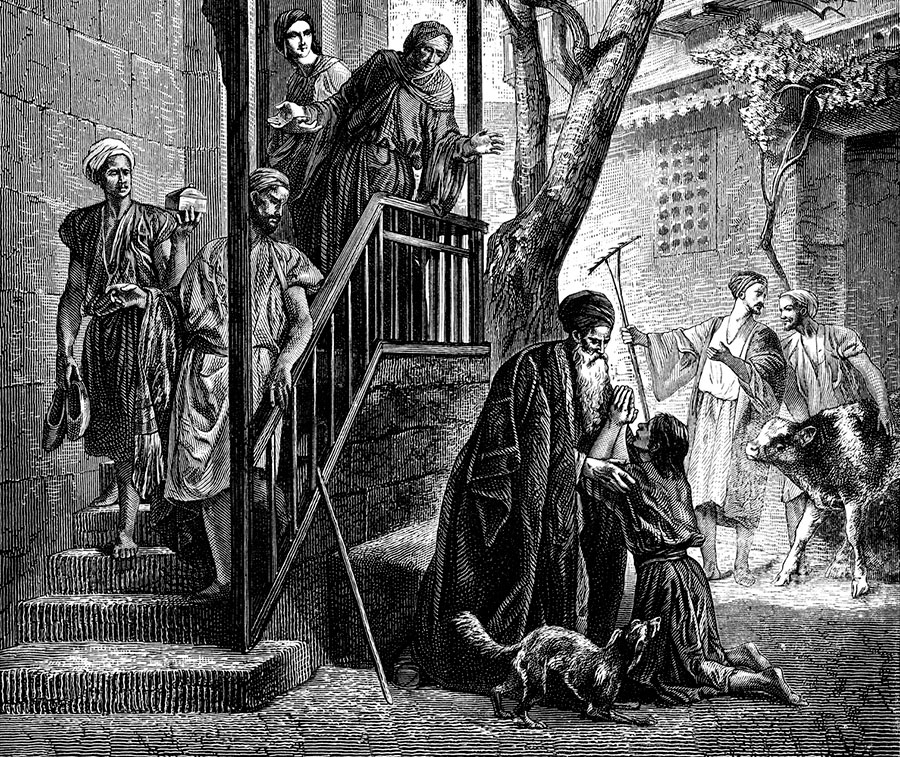

So why, in the face of these warnings to do otherwise, are many of us still calling God “Father”? This question is one I’ve been pondering since first encountering feminist thought on this subject thirty years ago, while doing research on a book about Jesus. As everyone knows, the teachings of Jesus are permeated with references to God as Father, and he was himself unforgettably father-like in his compassion for the lost sheep of the house of Israel and for children. “Be merciful,” he once said to his disciples, “even as your Father is merciful.” I thought then and still do that if calling God “Father” is contrary to the moral, social, and spiritual health of humanity, Christianity is defective at its core.

But is it? In my presentation today I want to convey some of the reasons why I think it is not, and why I regard the feminist critique of calling God “Father” as itself seriously in need of critique. The thesis I propose may be briefly stated as follows: The word father, rightly understood, connotes an irreplaceable social and cultural acquisition that is foundational for the emergence of a truly human, healthy, and happy civilization—hence, the privilege of calling God “Father” is likewise an irreplaceably beneficent sign of God’s loving care and will for the world as this is made known through the Scriptures and traditions of synagogue and church.

With this thesis I seek to address five overlapping issues arising from the critique in feminist theologies of “Father” as a name for God: (1) the difficulties encountered when refuting this name in favor of others; (2) the centrality and significance of “Father” as name for God in biblical culture; (3) the true meaning of “father” in human culture; (4) the foundational importance of fatherhood for human culture; and (5) receptivity to God as father in the emergence of high cultures of fathering.

Difficulties in Replacing “Father”

Feminist theologies have rightly emphasized that the reality we refer to as God is beyond gender. The Bible itself makes this point in Deuteronomy 4:15–17, where Israel is told that because “you saw no form of any kind on the day Yahweh spoke to you at Horeb out of the fire, therefore watch yourselves very carefully, so that you do not become corrupt by making an image in the shape of anything whatever; be it a statue of man or of woman . . . .” In feminist theologies this insight is resorted to as a basis for putting distance between the verbal symbol father and its referent, between language about God and the being of God. It is emphasized that the being of God is ineffable, mysterious, beyond imagination. The term father is merely a symbol or metaphor. God is not literally our Father. Other metaphors are equally valid. In fact, to think of God exclusively as father, many suggest, is sexist and idolatrous. It privileges males. With thoughts like these, calling God “Father” is relativized, marginalized, or dismissed altogether.

However, refuting “the father” in God in this way has proven easier than filling the void left by its absence. “We are about to learn what happens when father-gods die for an entire culture,” wrote Naomi R. Goldenberg several decades ago in her book, Changing the Gods: Feminism and the End of Traditional Religions. But what she observed taking place was a “turn toward inwardness” from which a multiplicity of variously gendered (or genderless) gods or god images are emerging, none of them predominant as yet, she noted, and some less benign than others.4 “Image-making itself,” she concluded, “may be the only common ground achievable among the devotees of these varied religious alternatives.”5 In her recent survey of the history of feminist theology Rosemary Ruether notes a similar “plurality of identities” for God and concludes her study by affirming this and calling for what she terms a “praxis of multi-religious solidarity and syncretism.”6 Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza seems to concur when advocating what she calls “a discourse embodying a variegated reflective mythology” as the path ahead for feminist religionists.7 This collapse of “normative assertions” in feminist theologies is also noted and affirmed in a recently published compendium of essays on this subject by upcoming feminist theologians.8

The European philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche observed something similar happening at the close of the nineteenth century. In one of his monologues in Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche posed the question, “Why Atheism Today?” and went on to state as an answer what he said he learned through a great many conversations, namely, that “the ‘father’ in God has been thoroughly refuted. . . . Also his ‘free will’: he does not hear—and if he heard he still would not know how to help. Worst of all,” Nietzsche wrote, “he seems incapable of clear communication: is he unclear?” Nietzsche asks this, then replies, “This is what I found to be causes for the decline of European theism.” Nietzsche went on to indicate what he thought would be the consequences of this—not the end of religion, but the emergence of new religions. “The religious instinct is indeed in process of growing powerfully,” Nietzsche wrote, “but the theistic satisfaction it refuses with deep suspicion.”9

It appears that refuting the father in God creates a void that is exceedingly difficult to fill. Nietzsche himself sought to fill it with his own well-known “philosophy of the future” at the center of which stood his famous Übermensch (superman), a powerful, self-willed type of man whom Nietzsche describes as utterly disdainful of pity and willing to enslave others for the sake of a truly civilized elite, one, he said, that “will grow, spread, seize, become predominent—not from any morality or immorality but because it is living and because life simply is will to power.”10 By contrast, present-day feminist theologians, while united against what they term “the Western cultural sex/gender system,” seem vague or uncertain about what will or should take its place.

The ultimate ineffability of God is not to be challenged. We see and know only in part. All language for God (all language, in fact) is analogical, drawn from human experience, and no more than an approximation of the reality to which it points. The mistake is in misconstruing the importance of what is signified by the word father. While it is true that words are mere approximations of the realities to which they point, when speaking to or about God, some ways of speaking, some analogies, are more appropriate, more accurate, more adequate, more meaningful, more conducive to evoking or “naming” who or what God really is and wants of humanity than are others. And, whether consciously or not, we do make judgments in this regard, both as individuals and collectively, so that over time specific ways of naming, addressing, and talking about God inevitably take hold and become defining, distinguishing features of given cultures or civilizations.

God as “Father” in the Bible

The Bible is a case in point. Its pages reflect a culture in which distinctive ways of invoking, addressing, and thinking about God were embraced and then advocated, after a prolonged struggle with religious alternatives similar to those being advocated today. Imaging God is prohibited, but God does reveal his name and is so named. The name, revealed to Moses at the burning bush and used some 6,000 times in the Hebrew Scriptures, is not Baal (connoting son), not Ashteroth (connoting mother), not Anath (connoting daughter), but Yahweh (connoting father). The identification of Yahweh, the God of Israel, with El, the father of the gods in Canaanite religion, is very explicit in biblical literature.11 The prevailing assumption that the ascription of fatherhood to God (admittedly pervasive in the Greek New Testament) is infrequent in the Hebrew Scriptures is thus incorrect and the result of an oversight. The name Yahweh means, “he who causes to be” or “creates” and, as such, in itself, signifies “father” in a culture where children were viewed as originating in the semen of the male. Thus, the psalmist writes in Psalm 100:3, “Know that Yahweh, he is God, he has made us, and not we ourselves.” To the rhetorical question posed by the prophet Malachi, “Have we not all one father, has not one God created us?” (2:10), the presumed answer is: “Yes! We do indeed all have one father; one God, namely Yahweh, has created us.”

It was therefore no innovation or break with tradition when Jesus taught his disciples to pray, “Our Father, hallowed be thy name” (Matt. 6:9), or when Paul greeted his Gentile converts with the words, “Grace to you and peace from God our Father” (Rom. 1:7; 1 Cor. 1:3; 2 Cor. 1:2; Eph. 1:2; Phil. 1:2; Col. 1:2). The Father of whom they spoke was the God of Israel, and this is why pronominal references to this God throughout the Bible are always masculine—not because God is male, but because God is father (Yahweh).12 It is “he” (the father) who is rock-like, warrior-like, husband-like, and yes, mother-like. It is “he” (the father) who revealed himself in and through Jesus Christ as a friend of sinners. Father is his name. It is simultaneously a function. God is “Father” and acts like a father.13 “As a father is compassionate toward his children,” the psalmist writes, “so Yahweh is compassionate toward those who fear him” (Psalm 103:13).

The centrality and emotionality of this name in biblical culture accords with the “intuition” that invoking this gracious God who bears this name and following in his ways is life-enhancing for individuals and cultures. The biblical strictures against worshiping “other gods” bearing other names, connoting other roles and espousing other values exist not simply because they are alien, but because they are inadequate, deviant, potentially destructive (Deut. 30:15–20), “empty cisterns that hold no water” (Jer. 2:13). Adhering to Yahweh alone will bring “blessings,” not “curses” (Deut. 28). Respect for Yahweh is the beginning of wisdom (Prov. 1:7). “Look, today I am offering you life. . . .” (Deut. 30:15). “Two things I beg of you, do not grudge me them before I die [prays the editor of the book of Proverbs]: keep falsehood and lies far from me, give me neither poverty nor riches, grant me only my share of food, for fear that, surrounded by plenty, I should fall away and say, ‘Yahweh—who is Yahweh?’ or else, in destitution, take to stealing and profane the name of my God” (Prov. 30:7–9).

The assumptions underlying this biblical naming of God are thus just the opposite of those espoused by feminists who view it as symbolic of a male power that is demeaning to women and destructive of social health. Whose assumptions are correct?

The Meaning of Father in Culture

These assumptions can be tested by looking at communities in which each of them is operative. Refute the “father” in God and in culture and see what happens. See what happens in societies where God is honored as caring, gracious father and human fatherhood is vital and strong.14 These assumptions can also be tested by careful analysis. We can think through what fatherhood is and represents. This is an issue that ought to be the focus of an intense debate, but feminist literature to date is notable for its neglect. The term father itself is avoided in feminist theologies. Instead, we read of androcentric families headed by male patriarchs whose dominance must be curtailed if we are to restore the health of society.15

To be sure, fathers are males, but not all males are fathers in the traditional meaning of this word, that is, caretakers of their own children. The male assumption of this role is not something that can be taken for granted. Males can and do become fathers to their children, but the circumstances and conditions under which this is possible are complex and greatly misconstrued when the father role is simply stereotyped as male assumption of power over women.

On the contrary, for the male to become father to his own children, certain cultural developments must occur involving males and females. First, because male involvement in the reproductive process is so marginal (confined as it is to a momentary act of sexual intercourse), the very concept of the male as father to his children is fragile, totally dependent on the culturally acquired knowledge that male semen deposited in a woman’s womb is in fact what initiates the growth of a fetus and the birth of a child nine months later. The link between children and their mothers is biologically transparent. The link between a male father and a given child is conceptual, built on the shared awareness among men and women of the role semen plays in procreation.

But of course, this awareness alone will not give rise to a culture of fatherhood in the sense of males actually caring for their own children. For the biological link to be drawn between a specific male and a specific child and for the male to have access to his child and participate in its care, at least four additional conditions are prerequisite. First, the impregnated female must be willing to inform the male that a given child in her womb is his; second, the male on his part must have confidence in her veracity—he must trust that this child is truly his and not someone else’s; third, the female must permit him to be this child’s father and grant him a share in its custodianship and care when it is born. Then, fourth, the male must accept this newly assigned role as father to his own child and take steps to be there when his child is born, embrace it as his as well as hers, and assume his share of responsibility in its care and nurture.

The power to grant or deny the male a role as father of his own children vests women with a key role in the construction of fatherhood. Fatherhood occurs at the conjunction of two relationships, writes anthropologist Peter Wilson in his remarkable book, Man, the Promising Primate: at the intersection of the pair-bond between a man and a woman and the primary bond between a woman and her child.16 It is the overlap of these two relationships that produces the possibility of a third—that between father and child. “This third relationship,” he writes, “differs from the other two in that it is mediate, the product of the conjunction of the other two, which are immediately generated by the biological conditions of reproduction, nurture and [sexual] attraction.”

Pair-bonds (between adult males and females) and primary bonds (between mothers and children), Wilson writes, are rooted in nature, whereas the bond between a father and his own child is a cultural novum arising solely from a male’s pair-bond with the child’s mother. Wilson argues that the relation of father and child was the elementary social relationship in the evolutionary emergence of human beings, a relationship constructed by transforming natural circumstances and “materials” through thoughts and promises. It is for this reason that he identifies human beings in their uniqueness over against all other orders of life as “the promising primate,” for it is only through covenants and promises between certain males and females that this new relationship of father and child is made possible, and it is this, he argues, which distinguishes human culture from primate existence.17 This historic development is intuitively acknowledged in Genesis 2, where the Bible characterizes the advent of woman as the “one flesh” partner to man as the crowning act of creation. Only when this had happened, the biblical narrator implies, could human history as such begin.

Fatherhood as Cultural Foundation

So far as I know, there are, in fact, no surviving human cultures on earth that do not support and encourage, in some manner, the institution of the two-parent father-involved family as just described. In a study of The Father in Primitive Psychology, anthropologist Branislaw Malinowski reports on his research among primitive tribes of the South Pacific who did not yet know (and actually resisted knowing) that semen played a role in the birth of children.18 It was their belief, rather, that women bear children of themselves with the aid of supernatural spirits. As a consequence they had no word for father and there was no special relationship between a male and his own children. Even so, Malinowski reports, it was strongly felt that a woman when giving birth to children, should have a male companion to whom she was married and who would assist her in their care.

The father-centered family structures and values enshrined in the Christian Bible date back to two of the oldest civilizations on earth, those of ancient Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt. In both, the male role in procreation was clearly understood, and men were encouraged to marry and have children they knew to be theirs. They were also taught how to take their role in loving their wives and training their children, as in the Egyptian Instructions of the Vizier Ptah-Hotep, dating to the middle of the third millennium B.C.19 Indeed, in the Mesopotamian Code of Hammurabi, dating to the first half of the second millennium B.C., there are 67 laws, no fewer, devoted solely to matters pertaining to the stability, health, and prosperity of the institution of the two-parent, father-involved family.20 This section of the code begins with the decree that only those are married who contract to be married (127), and that those who violate such a contract through adulterous affairs shall be subject to death by drowning (128). Biblical tradition affirmed, developed, and transmitted analogous family values to successive generations of Jews and Christians and eventually to Western culture. The breakdown of these values in our time may thus be viewed as an erosion not only of Christian values, but of human values espoused in one way or another by all human societies since the dawn of the first great human civilizations five millennia ago.

Today, those like Janet Giele, director of the Family and Children’s Policy Center at Brandeis University, who question how essential the father-involved family actually is for the well-being of our culture would do well to ponder this fact. It is Giele’s opinion that family strength should no longer be judged “by its traditional form (whether there are two parents), but by its functioning (whether it promotes human satisfaction and development) and whether both women and men are able to be family caregivers as well as productive workers.”21

There are reasons why societies without fatherhood do not exist and why, when fathers are absent or weak, societies weaken. Before heading further down this road we should consider carefully the toxic effects of father absence and why alternatives to fatherhood are so difficult to come by.

Others have already spoken to this issue. My own comments in this regard will be confined to a few observations on matters somewhat neglected, I think, in recent discussions. I refer to the insidious harm done by father absence in the earliest months and years of children’s lives. By simply being there in caring ways as significant “second others” for their infants to relate to in the very first months and years of their lives, fathers can be of enormous help to their children in putting distance between themselves and their mothers and so make possible a solid beginning on the long and sometimes difficult road to maternal separation and individuality.22 Fathers are also indispensable in establishing firm limits for their children during their “terrible twos,” when internal ego-controls are still fragile.23 In addition, through their special sensitivity for gender distinctions, fathers contribute immeasurably to the formation of the firm body-congruent gender-identities in both sons and daughters that are so essential to their emergent self-identities. Gender itself, of course, is a biological given, but gender identities are formed in response to subtle distinctions in parenting (many of them father-initiated) during the eighteenth to twenty-fourth month of children’s lives, right when they are learning to talk.24

A particularly sobering indicator of the importance of fathering in these early childhood years is provided by what is now known about the origins of homosexuality in men. While still a matter of dispute, the search since Freud for the genesis of this condition has repeatedly and consistently identified as one of its causative factors a pattern of parenting early in life, characterized by weak or absent fathers and overinvolved mothers.25 Charles Socarides, for example, reports that two-thirds of the approximately 400 adult homosexual men he has counseled suffered from a blurring of the boundaries between themselves and their mothers and acute gender confusion—and this is due, he writes, to an experience with “crushing mothers” and “abdicating fathers” during the very earliest pre-oedipal years of their lives. “The father’s libidinal and aggressive availability,” he writes, “is a major requirement for the development of gender identity in his children, but for almost all pre-homosexual children the father is unavailable as a love object for the child.”26 According to Seymour Fisher and Roger Greenberg, there does not appear to be a single even moderately well-controlled study of parental attitudes among male homosexuals that shows that they refer to their fathers positively or affectionately. On the contrary, they write, “With only a few exceptions, the male homosexual declares that father has been a negative influence in his life. He refers to him with such adjectives as cold, unfriendly, punishing, brutal, distant, detached. . . .”27

So urgent is a child’s felt need for a father during early childhood that one researcher has termed it “father hunger” and another likens the father in his role in the second and third year of his children’s lives to that of a lifeguard rescuing a child desperately trying to reach shore while being pursued by a dragon. When men abandon their families at this age and stage, it is not unusual for their children to have terrifying nightmares from which they awaken screaming for their fathers.28

Original Sin & Hopeful Signs

In the final pages of his book, Crossing the Threshold of Hope, Pope John Paul II writes of “the rays of fatherhood,” which are older than human existence and which “shine forth from God illuminating man and his history.” “These rays encounter a first resistance in the obscure but real fact of original sin. This,” he writes, “is truly the key for interpreting reality. Original sin is not only the violation of a positive command of God but also, and above all, a violation of the will of God as expressed in that command. Original sin attempts, then, to abolish fatherhood, destroying its rays which permeate the created world, placing in doubt the truth about God who is Love.”29

These words challenge us to look at the ways in which our culture may be losing contact with the God who is Love through its cavalier attitudes toward fatherhood. The manner in which we are currently inducting our youth into the mysteries of human sexuality comes sharply into focus in this light. What distinguishes human sexuality from its predecessors is the drawing together of male and female into a powerful, enduring sexual bond. This drawing together is preparatory in our species for the presence, so essential to its survival, of an infant’s two parents at the time of its birth.

To deny or repress this inherently covenantal and procreative aspect of human sexuality is dehumanizing and utterly dangerous for the welfare of children and societies. It is for this reason that cultures that care about their future have devised clear and unambiguous guidelines for helping their youth make the precarious transition from adolescence into their first full sexual embrace at the time of marriage. But with the advent of contraceptives the idea that human sexuality can be harmlessly exploited for its pleasures alone has become culturally acceptable.

In the wake of this development, not just older sexual values, but the words and institutions heretofore associated with those values have changed. Instead of fornication and adultery, we speak now of premarital and extramarital sex, as though sexuality in humans were not intrinsically marital (that is, covenantal). Small wonder that the rationale for the institution of marriage is no longer self-evident and that random sexual relations of shorter or longer duration have become commonplace, with the formalities previously associated with sexual cohabitation increasingly viewed as optional.30

The availability of contraception, and especially the use of chemical contraceptives by women, states anthropologist Lionel Tiger in his recent book, The Decline of Males, has turned out to be a revolutionary force in human behavior, in that it permits men especially to absolve themselves of any responsibility for the procreative consequences of their sexual activities. Who could have predicted, he writes, “how rapidly male resistance would grow to marrying pregnant partners? Who could have tracked in advance the rate at which women themselves would seek other remedies?”31 The price we are paying for these now entrenched patterns of depleted, exploitive, irresponsible sexuality are indeed extremely high: epidemic venereal diseases, abortion on demand, divorce on demand, and a drastically weakened fatherhood. Yet the trends seem almost irreversible. If it is true, as Pope John Paul II has said, that “original sin attempts . . . to abolish fatherhood, destroying its rays which permeate the created world, placing in doubt the truth about God who is Love,” ours is a culture in the grip of original sin.

When tempted to despair, however, I recall the religious factor. Moses at the burning bush, when all alone and challenged by an unknown God to rescue his people, had the good sense to ask, “What is your name?” Countless numbers of men and women are asking the same question. Who is the God who created this mysterious universe? What is his name, and what is his will?

Pastoral psychologist Theodore Stoneberg has recently stated his belief with stark and prophetic simplicity: “That the overarching task for the twenty-first century is to reconnect manhood and fatherhood in the lives of Western men.”32 Those who initiated this conference were seemingly moved by similar strong convictions. Others have been similarly inspired to write books on this subject and found institutes, and there are many others.

Two decades ago the leader of one of the more successful movements in our time for restoring traditional family values, James Dobson, wrote quite openly and frankly of having received a revelation from God to the effect that “if America is going to survive the incredible stresses and dangers it now faces, it will be because husbands and fathers again place their families at the highest level on their system of priorities, reserving a portion of their time and energy for leadership within their homes.”33 There are many hopeful signs that the rays of fatherhood shining forth from God into created existence have not been extinguished, but are still shining.

Notes:

1. A recent poll of clergy of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), reported in The Christian Century (September 8–15, 1999), found that only one in nine thought “God is best understood in masculine terms” (p. 844).

2. Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza, Sharing Her Word: Feminist Biblical Interpretation in Context (Boston: Beacon Press, 1998), p. 3, n. 10.

3. Ibid., p. 180.

4. Naomi R. Goldenberg, Changing of the Gods: Feminism and the End of Traditional Religions (Boston: Beacon Press, 1979), p. 37.

5. Ibid., p. 140.

6. Rosemary Radford Ruether, Woman and Redemption: A Theological History (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1998), p. 280f.

7. Schussler Fiorenza, Sharing Her Word, p. 178.

8. On this development, see the essays in Horizons in Feminist Theology, Identity, Tradition, and Norms, Rebecca S. Chopp and Sheila Greeve Davaney, eds. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1997).

9. Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future, Translated with commentary by Walter Kaufmann (New York: Vintage Books, 1966), p. 66.

10. Ibid., p. 203.

11. Frank Moore Cross, Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic: Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973), p. 47, notes that many of the attributes and epithets attributed to El in Canaanite texts are reproduced in our biblical sources. Examples are: El elyon, El shaddai (Gen. 14:19; Ex. 6:2f.), El olam (Gen. 33:20), and El Bethel (Gen. 35:7); see also Josh. 22:22, where the two and one-half trans-Jordan tribes profess their faith by declaring “The El [father] of gods; Yahweh, the El [father] of gods. . . .”

12. The father-language for God in both Testaments has been reviewed many times, most recently by Francis Martin, The Feminist Question: Feminist Theology in the Light of Christian Tradition (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1994), pp. 265–292.

13. Yahweh is pictured occasionally as acting with a tenderness and care that is mother-like (Is. 42:14; 45:10; 49:15; 66:13), but nowhere in either Testament is he ever addressed as mother or said to be mother. On these linguistic distinctions (simile versus metaphor) and their importance, see Roland M. Frye, “Language for God and Feminist Language: Problems and Principles,” in Speaking the Christian God, pp. 17–43. Frye characterizes the symbol “father” for God as a “structural metaphor” underlying “the entire organism of belief . . . to which different parts of the living body of faith connect and through which they function” (p. 42). On these issues, see also John W. Miller, “Depatriarchalizing God in Biblical Interpretation: A Critique,” Catholic Biblical Quarterly 48 (1986), pp. 609–616.

14. For a recent summary of the research on these issues, see David Popenoe, Life Without Father, for compelling new evidence that fatherhood and marriage are indispensable for the good of children and society (New York: Martin Kessler Books, The Free Press, 1996). For the statistics, see Wade F. Horn, Father Facts, 3rd ed. (National Fatherhood Initiative, 600 Eden Road, Building E, Lancaster, PA 17601).

15. This is the way fatherhood is referred to in the Dictionary of Feminist Theologies, Letty M. Russell and J. Shannon Clarkson, eds. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996), p. 205. This recently published compendium has no article on “fathers/fatherhood” corresponding to its article on “mothers/motherhood.” Instead, an article on “patriarchy” refers to the “rule of the father” described as “male heads of families over dependent persons in the household” (p. 205).

16. Peter J. Wilson, Man, The Promising Primate: The Conditions of Human Evolution, 2nd ed. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1983), p. 59.

17. Wilson, p. 95. For a similar perspective on fatherhood as the transitional event in the emergence of “humanity,” see Margaret Mead, Male and Female: A Study of the Sexes in a Changing World (New York: Morrow, 1949), pp. 183–200.

18. Branislaw Malinowski, The Father in Primitive Psychology (New York: W. W. Norton, 1927).

19. For a translation, see James B. Pritchard, ed., Ancient Near Eastern Texts (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), pp. 412–418. Line 325 reads as follows: “If thou art a man of standing, thou shouldst found thy household and love thy wife at home as is fitting.”

20. For a translation, see ibid., pp. 164–180. Altogether there are 282 case laws; family case laws are grouped together in a middle section, case laws 128 to 195.

21. Janet Z. Giele, “Decline of the Family: Conservative, Liberal, and Feminist Views,” in Promises to Keep: Decline and Renewal of Marriage in America, David Popenoe, Jean Bethke Elshtain, and David Blankenhorn, eds. (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1996), p. 101.

22. See Richard Atkins, “Discovering Daddy: The Mother’s Role,” in Stanley Cath, et al., eds., Father and Child: Developmental and Clinical Perspectives (Boston: Little, Brown, 1982), pp. 139–149; Stanley Greenspan, “‘The Second Other’: The Role of the Father in Early Personality Formation and the Dyadic-Phallic Phase of Development,” ibid., pp. 123–138.

23. See James M. Herzog, “On Father Hunger: The Father’s Role in the Modulation of Aggressive Drive and Fantasy,” ibid., pp. 163–174.

24. The research leading to this breakthrough discovery is reviewed by Ethel Person and Lionel Ovesey, “Psychoanalytic Theories of Gender Identity,” Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, 11 (1983), pp. 203–225.

25. The research is summarized by Henry Biller, Fathers and Families: Paternal Factors in Child Development (Westport: Auburn House, 1993), as follows: “The close-binding mother-son relationship that sometimes precedes the expression of homosexuality in males frequently takes place in the context of a distant or otherwise inappropriate father-son relationship” (p. 183).

26. Charles W. Socarides, “Abdicating Fathers, Homosexual Sons: Psychoanalytic Observations on the Contribution of the Father to the Development of Male Homosexuality,” in Cath, et al., Father and Child, p. 512. For similar views, see Richard C. Friedman, Male Homosexuality: A Contemporary Psychoanalytic Perspective (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), who cites research pointing to childhood gender disturbance (more specifically, a feminine or unmasculine self-concept during childhood due in part to a disconnection with the father) as “the single most important causal influence” in the emergence of “predominant or exclusive homosexuality in men” (pp. 74, 77).

27. Seymour Fisher and Roger Greenberg, The Scientific Credibility of Freud’s Theories and Therapy (New York: Basic Books, 1977), p. 242.

28. See James M. Herzog, “On Father Hunger: The Father’s Role in the Modulation of Aggressive Drive and Fantasy,” in Cath, et al., Father and Child, pp. 164f. Stanley Greenspan, “The Second Other,” pp. 123–138.

29. John Paul II, Crossing the Threshold of Hope (Canada: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), p. 228.

30. On these trends and what they signify, see David Popenoe and Barbara Dafoe Whitehead, Should We Live Together? What Young Adults Need to Know About Cohabitation Before Marriage: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Research, The National Marriage Project (Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 1999). They report that “over half of all first marriages are now preceded by cohabitation, compared to virtually none earlier in the century” (p. 3).

31. Lionel Tiger, The Decline of Males (New York: Golden Books, 1999), p. 259.

32. Theodore Stoneberg, “The Tasks of Men in Families,” in The Family Handbook, Herbert Anderson, Don Browning, Ian S. Evison, Mary Steward Van Leeuwen, eds. (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1998), p. 71.

33. James Dobson, Straight Talk to Men and Their Wives (Waco: Word Books, 1980), p. 21.

John W. Miller is Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies, Conrad Grebel College, University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. An ordained minister of the Mennonite Conference of Eastern Canada, he holds a Th.D. from the University of Basel. He is the author of Calling God “Father”: Essays on the Bible, Fatherhood, and Culture (Paulist Press, 1999). He and his wife Louise have been married for 50 years and have three children and eight grandchildren. This article was given as a paper at Touchstone’s 1999 conference on fatherhood.

John W. Miller is Professor Emeritus of Religious Studies, Conrad Grebel College, University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. An ordained minister of the Mennonite Conference of Eastern Canada, he holds a Th.D. from the University of Basel. He is the author of Calling God “Father”: Essays on the Bible, Fatherhood, and Culture (Paulist Press, 1999). He and his wife Louise have been married for 50 years and have three children and eight grandchildren.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on fatherhood from the online archives

14.1—January/February 2001

The Christian Heart of Fatherhood

The Place of Marriage, Authority & Service in the Recovery of Fatherhood by John M. Haas

more from the online archives

33.2—March/April 2020

Christian Pro-Family Governments?

Old & New Lessons from Europe by Allan C. Carlson

14.1—January/February 2001

The Christian Heart of Fatherhood

The Place of Marriage, Authority & Service in the Recovery of Fatherhood by John M. Haas

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor