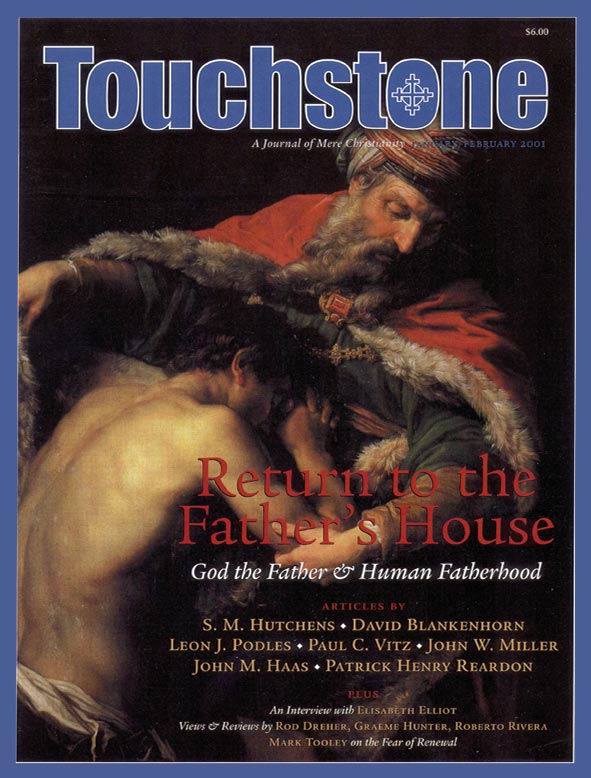

View

The Craft of Fatherhood

S. M. Hutchens on Christian Fatherhood

Fatherhood is a craft to be passed from father to son. However inattentive a son I have been, I am at least perceptive enough to recognize my own father’s mastery. Reflecting on this, however, has brought me to a number of perplexities. I find I do not have much understanding of the wellsprings of his motivation, such as I might have if I were his brother rather than his son. My father says little of his past. Nor can I recall his having spoken to me or my brother of any philosophy of child raising, or indeed, of his philosophy of anything; he simply was what he was and did what he did. He has never taken us on a grand tour of his mind. This would sound like chatter or immodesty to him, and he is given to neither. If I would share my advantages as his son with others, I must reconstruct a mind and a philosophy out of surmises and general impressions.

It is clear to me that my father was strongly impressed very early on with the seriousness of his duty as a father, and purposed in his heart to do right by his sons. This resolve took form around his intuition of the father’s irreplaceability in showing his children the shape of reality and helping them come to terms with it—having a realistic idea of what is real, and defining themselves well against it. This aspect of the psychology of fatherhood has been mentioned by Paul Vitz (“The Father Almighty: Maker of Male & Female”), and I strongly concur with his remarks.

Reality & Religion

Someone might say that the most important thing a father can do for his children is to teach them to love and to fear God. That is correct, but there is a danger in thinking this way that has always weighed upon me, having to do with the connection of God with religion. What too often happens when we try to teach our children the love and fear of God is that we teach them religion instead. Now understand what I am saying. True religion is communion with Christ in his Church and is a wholly good and desirable thing. But there is a sense in which we use the term to represent sensibilities that normal men find unmanly and repellant, and which in fact have little to do with the love and fear of God, at least as men are created to understand it. Ann Douglas spoke of these in The Feminization of American Culture, and Leon Podles once again in The Church Impotent. C. S. Lewis mentions the lack of this religious sensibility as a personal defect of his. He makes much of it in the Screwtape Letters, as a general dislike of “church” that the tempter is wise to exploit. It was modest of him to put it this way, but I am not sure it should be judged a fault right off. My father served me and my brother well by placing the ratio of belief and worship in the sphere of reality rather than of religion. It was because of this that we felt no obligation to the essentially feminine pieties that have been mentioned by these authors as so common in the West and so obnoxious to men.

My father taught his children to honor and serve God because it is meet and right so to do—because God is, and is Who he is, the Source and Ground of all that is real and true. We do not worship him principally because we have a religious side of our nature that must be satisfied if we are to be whole people, much less because there are prudential reasons to be religious, and very much less because we feel affectionate toward him. He is the one with whom we have to do, and we must become reconciled to him as his being demands, in a way precisely analogous to that in which we reconcile ourselves to other realities over which we have no control, and which are only moved when approached on their own terms. There is not a grain of sentimental religiosity in this—it is the brute fact Peter acknowledged with “To whom shall we go?” and what an author many of us know has said when he observed that he is not a tame lion.

One might say, we must teach our children the love of God, and where is the love of God in this? To that I would reply that we commonly, even customarily, confuse love with affection, when instead it has much more to do with obedience. The Lord did not say, “If you love me, cultivate a fondness for my person,” but “If you love me, obey my orders!” Affection—well, something much stronger than this, for which we can properly use the word “love”—will follow as the fruit of obedience, but it is not at the root.

The Father as Priest & Soldier

The outward-facing, so to speak, upon which the engagement of the reality of which God is the principal part depends, is an essentially male quality, passed on mostly through the father. In the context of the family, and by extension the Church, the father’s role with respect to what lies without is priestly. It is he who is fitted for the reconciliation of his home and all who are within it to the greater reality without. He defines and protects his wife and his family with his body and his name, and guards them either with his diplomacy or his sword. It is he who, as the Scriptures indicate, primordially contains the woman, and not the other way around. It is he who is the defining head from whom she and her children devolve. His maleness is the indispensable symbol of the wholeness of man who is male and female. The father who serves his family best is the one who communicates God to them principally as the one outside ourselves with whom we have to do, and only secondarily as the one who is within us, for the God within, if undefined and uncontrolled by the God who is without, is a demonic self.

My father’s kind of fatherhood laid the groundwork for this understanding in me. It became clear early on that in our home we did not serve ourselves, much less paternal whim, but lived our lives according to an order that was outside my father’s jurisdiction and to which he himself submitted. It did not matter, for example, whether anyone wanted to go to church or not; unless we were ill, we went to church. If there was a blessing to be found there, it was because the prescribed duty gave rise to the occasion, as the law of the Old Covenant gave rise to the gospel of the New. One honored God simply because he was worthy of honor; one saluted the divine uniform no matter how one happened to feel that day about its incumbent.

Along with this subordination of religious feeling to a concern for the shape and feel of external reality—which is, we have learned, a perennial concern of little boys—came certain salubrious immunities. One of them is to the marketing of the Faith, which appeals primarily to the viscera, depending most, I think, upon the prospect of having one’s Christianity make one a happier, perhaps richer, emotionally satisfied person, a more successful parent, a better lover, and so forth. It may indeed do all these things. (I believe it was Edmund Morgan who somewhere said that Puritanism died because it could not survive its success at making comfort a fruit of Puritan virtue.)

The proper honor of reality that our father taught us, however, gave the lie to these prospects so often presented as the proximal issue of faith. It helped us remember the Scriptures to the contrary, that believing what one should, and doing what one ought, will sometimes make us miserable, rob us of the ability to accomplish what we desire, drive those we love away from us, confuse and mystify us, and in the end give us death, even a very lonely and terrible death. Real faith had to do with putting off secondary happiness for the primary while in the world, that is, for blessedness in the sense that Plato taught, as that of the man who was happy simply for doing what he knew to be right. And it meant that supernal blessedness must be understood as beyond death and judgment, not to be sought in this world. Real manliness has much to do with the deferral of gratification.

Only in this mode of understanding, I came to see, could one say with full conviction, “The Lord is good and full of loving kindness; his mercy endures forever,” for if mere feelings are summoned to endorse the statement, they take strong offence, finding overwhelming evidence to the contrary. In fact the Lord is Good, but he is not Nice: we must find whatever niceness is his in the context of his goodness. He is full of grace, but not of excusings. We must find his forgiveness within his grace. His mercy endures forever, but there is an end to his patience. Patient he is, but in accordance with the particular character of his mercy.

This is bad news, I think, in the broad stream of what is called religion, whether liberal or conservative, which depends very much on the satisfaction of the religious consumer, yet it has saved my faith many times. This is why I am such a strong advocate of the manly, soldierly, reality-conscious faith my father gave me, not by preaching, but by doing his duty in serving God before his sons. He did not analyze it, but analysis shows it to be a great thing in a humble package, pursued less by calculation than by solid instincts undergirt by what the Romans called virtus—translatable as “manliness.”

Resistance & Appreciation

It has been my experience that there is a natural and understandable feminine resistance to this quality, a resistance that doesn’t necessarily come with feminism. I have seen it in my mother and wife, both of whom are good and godly women who love their men and are as willing to let them be men as any woman could. There is always a desire on the part of women to domesticate us. This ritual, or contest, if you will, is part of the Dance—part of the fascination that women hold for us and the potential delight of their company. But there is also a fear in women of the stark and often aggressive otherness of the man.

Let me tell you what I mean by this. In the case of both my mother and my wife, their resolution to allow my father and me to be men and to do what men feel responsible for doing was questioned primarily in our strictness with our children, especially when they challenged our authority. This, I have found, is a frequent area of tension between good women and good men. As reasonable and realistic as our discipline seemed to us, and as important as it was in teaching the children the shape of reality and the nature of God, frequently it seemed to them unduly harsh. (Of course, a man should let his wife entreat him—and she should do it privately—for the children’s sake, for we will make mistakes, and we should allow her to change our minds if necessary.) But what we brought them in our overrulings, in the face of their misgivings, was an orderly, peaceful home, with children who were happy, obedient, and respectful (and so lovable), at first because there was a real and present danger in crossing the Old Man by being otherwise, but finally because the children came themselves to love and treasure the peace of their father’s house, where the best music has always been the laughter of women and children, even when they are laughing at the old bear who runs it.

The other thing that has reconciled our women to the gruff and hairy beast is that he has been loyal to them. This too is a manly quality. It is a particularly reprehensible failure of virtue when a man becomes a traitor to his wife, who is his homeland and regiment, and goes off with another woman. This is another reason why it is so desperately important for men to subordinate their emotions to their convictions, and important for the woman to encourage this kind of manliness in her man. Every vagrant desire of the man to follow his feelings rather than the loyalties that come from simple and (note the metaphor here) bull-headed conviction of the mind on what is true and false, good and evil, leads toward the abandonment of the woman.

My first conception of this oration was a eulogy in the form of “what my father taught me.” But as I reflected on many small things, one large one came to fill my vision—that my father had in all likelihood established and preserved the faith of his sons simply by being a man. Being a man in this sense isn’t complicated—it can be done by the youngest and least experienced of men—but it is hard, and always has been.

To the man the whole world seems like a woman offering him a fruit that promises what it cannot deliver, and we are called upon to follow the Lord in rejecting this temptation for the way of pain and glory. This is lived out in our vocation to take the piece of ground we have been assigned, claim it in the King’s Name, and deal with what we find there. The promise is not that we shall avoid pain or death, but that we shall have the fellowship (shall we translate it “comradeship”?) of his sufferings, and share in his Resurrection.

This essay is based on a talk given at Touchstone’s conference on fatherhood in 1999.

S. M. Hutchens is a senior editor and longtime writer for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on fatherhood from the online archives

more from the online archives

28.2—March/April 2015

Man, Woman & the Mystery of Christ

An Evangelical Protestant Perspective by Russell D. Moore

11.5—September/October 1998

Speaking the Truths Only the Imagination May Grasp

An Essay on Myth & 'Real Life' by Stratford Caldecott

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor