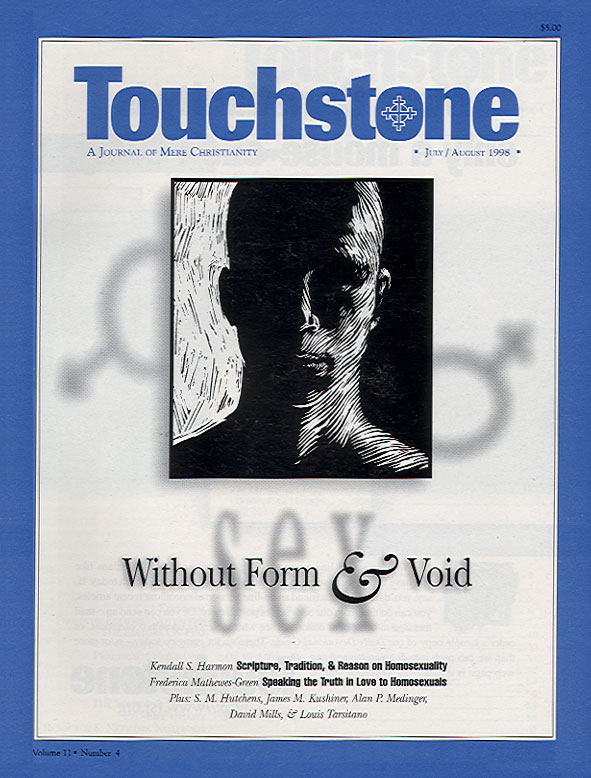

Facing the Homosexual Void

Speaking the Truth in Love to Homosexuals

by Frederica Mathewes-Green

I collect bumper stickers. I keep a notepad on my dashboard, and when I spot a new one, I jot it down. I like bumper stickers because they’re such a curious form of communication. Necessarily brief, every word, even every letter, must count. They’re the Morse code of culture.

Over the years I’ve seen a number of stickers that I’ve learned represent gay pride. There’s the Greek lambda symbol, the first letter of the word for homosexual. There’s the square rainbow symbol. And there’s the hot-pink triangle.

Some gay rights stickers are both cryptic and angry. “Hate is not a family value” and “God said, thou shalt not hate” are two examples. This can be puzzling, until you realize that you are the one they imagine is doing the hating. Another one reads, “Focus on your own damn family.”

“Gay” Patron Saints?

The interesting thing about these bumper stickers is that they indicate that a behavior has congealed into a movement, an identity. The movement even has an icon. In Same Sex Unions in Pre-Modern Europe, the late Yale historian John Boswell claimed to have discovered an ancient ritual for homosexual marriage. Plenty of other historians scoffed: the unions may have been linking people of the same sex, but they appeared to be on the order of a servant swearing fealty to a master in return for protection, or concerning adoption or inheritance. To find sexual intent in these rituals requires oversensitivity to the topic, interpreting such Scriptures as “Behold, how good and pleasant it is when brethren dwell in unity” with a leer and a wink.

Boswell finds his strongest support in the story of Saints Serge and Bacchus, and a seventh-century icon of the saints is on the cover of his book. These two constitute, according to Boswell, “by far the most influential set of paired saints.” Before their martyrdom in A.D. 309, they were soldiers in the Roman army and favored by the emperor.

“United not in the way of nature, but in the manner of faith,” their martyrology runs, “always singing and saying, ‘Behold, how good and pleasant it is for brothers to abide in oneness!’” Boswell goes to lengths to prove that homosexuals use the term “brother” to mean “lover.” He cites sources ranging from the Satyricon to Elton John, including ample “evidence” from the classified sections of homosexual newspapers.

In his treatment of friendship in The Four Loves, C. S. Lewis says wearily that “it has actually become necessary in our time to rebut the theory that every firm and serious friendship is really homosexual.” The “wiseacres” who propound this, Lewis says, take the lack of evidence for their theory as proof—“the absence of smoke proves that the fire is very carefully hidden. Yes—if it exists at all.”

Lewis goes on to make a telling point: Lovers pour all their attention into one another, unable to admit rival concerns; friends are united by an outside interest, whether merely a hobby or a grand and lofty cause. “Lovers are normally face to face, absorbed in each other,” says Lewis; “friends, side by side, absorbed in some common interest.”

Serge and Bacchus face us from the front of Boswell’s book, side by side. They do not even share a glance at each other, but look outward as if toward a common prize. Neither is as close to the other as each is to a third, one who hovers between and above them. In a small disk the face of Christ appears, uniting the friends who loved him unto death.

Loving Those at Odds

As might be expected, Christian orthodoxy has condemned homosexual practice through the ages. It has never been acknowledged as positive or acceptable, though it has been readily acknowledged as existing. Homosexual behavior has been treated like adultery and fornication, matter-of-factly and with no heightened sense of horror. A typical disciplinary note, written by St. John the Faster around A.D. 580, states that “any man who has been so mad as to copulate with another man” is restricted from Communion for three years, “weeping and fasting.” “But as for one who prefers to take it easy” and avoid the rigorous fasting, St. John says, let him fulfill the regular punishment: exclusion from Communion for fifteen years.

Nevertheless, and despite the speciousness of Boswell’s argument, Serge and Bacchus have been taken as the exemplars of same-sex marriage. The National AIDS Awareness Catalog offers a sixty-dollar silver medallion bearing an image of Serge and Bacchus, which it describes as a “Same Sex Union Medallion.” The reverse of the medallion is engraved, “Behold how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity.”

The gay rights movement does not hesitate to consume the emblems of the Christian faith. It has become aggressive, devouring the benefits that come its way from being a disempowered group. This is why its bumper stickers insist on our “hate”—in a culture that values victims and casts down the powerful, our hate is the very fuel of the gay rights movement. They need it to survive, and must find it, create it or ascribe it where it doesn’t exist. No one can come to great power in our culture without appearing to be hated by the powers that be, so they need us to hate them if they’re going to succeed.

This is why we must never give the appearance of hating them—but beyond that, we must simply never hate them. Our victory will be won in love or not at all.

The challenge is to love the homosexual person, and that can be done by recognizing in him our brother or sister, another fallen sinner in need of grace. Our sins are not more sweet-smelling than his—perhaps there are even some sins that we are proud of, things that our culture has told us are worthy of boasting, just as their subculture coaches them in gay pride. Are you proud of your beauty, or your possessions, or your status, or your wisdom? Vanity is one of the seven deadly sins. Are you, God forbid, proud of your virtue?

There’s a saying that we all stand on level ground at the foot of the Cross. If we feel disgust at the thought of standing there next to a homosexual but feel complacent about rubbing shoulders with an adulterer, we are not seeing things with God’s eyes. It is by his overwhelming mercy that any of us is saved. As we call our gay brothers and sisters to repentance and the difficult path of chastity, we should keep in mind that we were pulled from the same mire and won’t scrub off every stain till we’re in heaven.

Pro-Life Gays

Years ago I got a phone call from a man identifying himself as the founder of a new pro-life group—the Pro-Life Association of Gays and Lesbians. This group, PLAGAL, wanted me to be the speaker at their very first meeting. I agreed, feeling somehow touched that they would call on me, apparently believing I was worthy of this trust.

When the evening arrived, I found myself in a large room speaking to a very small group, about nine sweet-faced men who were gracious and eager to hear me. They had sent a press release to a number of outlets, including the Gay Fairfax cable channel, and to my surprise there was a TV team set up in the back of the room.

About halfway through my speech it became apparent why the media had turned out; a troupe of some thirty lesbians marched in to oppose me. They carried signs and were restless and hostile, and when the question-and-answer period came, they let me have it. Of course they had not heard most of the speech, so I had to patiently repeat my points, but they weren’t interested in listening to me anyway.

As the hour wore on, they became more bullying, and a vicious edge emerged. It was the most grueling experience I’ve yet had speaking on this issue, and as a result it was somehow the most blissful. I began to feel an unearthly peace and a love for each woman. I spoke more patiently and slowly, praising God constantly in my heart. When responding to each questioner, I would look at her and feel an overpowering love. In one instance, a woman who was berating me and insisting that aborting her twins was the best thing she’d ever done suddenly sat down in tears and began pulling tissues out of her bag. It was a healing moment and, overall, a blissful time for me, one unequaled since. This is inexplicable, except by the grace of God. I later wondered if this was a taste of what empowered the martyrs to go through hideous torture without apparently feeling pain.

Paul, the Charismatic

The most interesting thing, however, came at the end of the evening. When the women trudged out again and I came down from the podium, the nine kindly men surrounded me. They began telling me that they had been praying for me the whole time, they had been binding the evil spirits, they had been praying in tongues.

I thought, “Now I’ve seen it all. Now I’ve seen an elephant fly. Pro-life gay charismatics. Who’d have imagined it?”

But I wondered later, if they really loved the Lord (which I had no doubt they did), how could they go on living in defiant sin? Well, of course, they had had bad teaching that told them it was no sin. Someone had told them other ways to interpret the Bible passages, and coaxed them to be content in sin. This happens all the time, and not just with homosexuals. We all know heterosexuals who found a way to rationalize sexual sin; and if we include such sins as gluttony under the rationalizing umbrella, most of Christendom would be guilty at some point.

One of the men present that night I will call Paul. Not long after that evening, Paul wrote me a letter. In it he said, “I’m in great conflict about my life. I know that the way I live is not pleasing to God. I really love him and want to serve him. Sometimes I promise him that I’ll stop. But it always happens that time passes and I get so lonely. It’s such a lonely life. It gets to be too hard. Then I fall, and once that happens it happens a lot. And then I hate myself and can’t imagine why God would love me. It takes a long time to get back up from that. Each time it happens, it seems less worth it to make the promise again; I know I’m just going to fall. I feel helpless. I wish I could do better, because I really love God and want to serve him. I just don’t seem to be able to help it.”

I wrote back to Paul exhorting him to have courage, to make friendships with recovering gays in Exodus and similar organizations, and to pray. I felt somewhat futile, though. I can only imagine how hard this struggle is.

A Struggle Against Biology?

Paul put a face on struggling homosexuality for me, and helped me smudge the boundary between “good” celibate gays and “bad” active gays. There was a range there of sinners resisting to different extents, and succeeding to different extents. It seemed to me that a gay person striving to live chastely, but having an occasional fall, was indeed a sinner in grave sin, but one for whom hope remained as many times as repentance returned—up to seventy times seven. The greatest danger was that someone would come along and tell him, “You don’t have to repent any more. Give in, enjoy it. God made you this way.”

That is, of course, the primary argument in favor of gay rights: God made them this way. It’s in the genes. It’s ineradicable—a matter of inborn nature, not a choice. Some gays vigorously reject this idea; their cry is one familiar to feminism, “Biology is not destiny!” If they grant that homosexuality is inevitably written in the genes, then they have to entertain the proposition that women are programmed to bear and nurture babies, that men are programmed to be providers, and other awkward ideas. The package is too sticky, too fraught with politically incorrect implications. It’s safer to declare that homosexuality is a choice, a sexual preference, not a sexual orientation.

But the gay rights movement relies heavily on the assertion that biology is indeed destiny, that they were born gay and can’t help it. The flaw in this argument, of course, is that it hasn’t proved whether this ostensibly inborn gay impulse is one we should accommodate or resist. Gay rights activists simply haven’t proved that just because an impulse is rooted before conscious memory it should be indulged.

The test case is with pedophilia—attraction to young boys—which proponents could just as well claim to be an inborn urge. The man the homosexual mainstream (a.k.a the “Gaystream”) doesn’t want us to meet is Leland Stevenson. Stevenson is a spokesman for the North American Man-Boy Love Association (NAMBLA), which promotes homosexual encounters with adolescent boys.

Stevenson and his pals cause the “Gaystream” some awkward moments. When Heterodoxy reporter Paul Mulshine phoned a representative of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, Ms. Kane barked official non-support for NAMBLA, then recited the party line: “We believe that people should not be denied their civil rights because of the sexual orientation with which they are born.”

Mulshine stopped her there. “NAMBLA makes that exact same argument. They say pedophiles are born with their sexual orientation. Why should they be deprived of their civil rights?”

“I think I’m going to get off the phone now,” said Ms. Kane.

Orientation, Preference & Choice

The question of whether people are “born with their sexual orientation” ranks as the defining issue of homosexual rights. If “this is the way God made me,” proponents say, it’s nobody else’s business. Conservatives usually counter that sexual preference is not inborn, but a choice; as such, it deserves no special protection.

But the question is a red herring on both sides. First, that a behavior is freely chosen doesn’t automatically disqualify it from legal protection. We want to keep a Bible on our desk, or homeschool our children, without losing our job or our lease. Homosexuals demand to be granted the same rights—to be employed at a Christian school, to rent a room from a pious widow—without consideration of their sexual actions. Do we think our chosen behaviors are better than theirs?

Frankly, yes. First, no one pretends that homosexual behavior can be prevented, but we can decline to legitimate it. Society decides which behaviors to promote, such as recycling, or discourage, such as smoking, with an eye to the common good. Americans are far from agreed that homosexual behavior is so beneficial that it deserves specially protected status.

Second, we should admit that if homosexuality isn’t inborn, it’s rooted so deeply that it might as well be. Heterosexuals know just as well that their own preferences for blond or brunet, slim or shapely, are formed early in life, before conscious choice. It’s a matter of taste for which, as the saying goes, there’s no accounting. We were “born this way.”

This came home to me during a conversation with my friend Pam. She was impressed by a young man who had made a presentation at a meeting, because “he was tall, a real Saul, standing head and shoulders over everyone else in the room.” I wondered why anyone would consider height to be a plus. For me it was always short, dark, and brainy. My teenage dreamboat was singer Paul Simon: 5 feet 3 inches, with enough brains to make any girl swoon. All through my dating years I only liked the short guys, and I could have used all the “Gaystream” lines: I’ve been like this ever since I can remember. It’s not something I chose. Maybe I was born this way. I can’t imagine what it would take to change.

But this preference didn’t entitle me to keep a harem of short, brainy guys, charming as that image may be. One of the central insights of our faith is that, contrary to contemporary assumptions, what we want isn’t always what’s best; more often, it’s the opposite. Strong desire is not a “get-out-of-the-rules-free” card; flesh speaks with a commanding voice, but not the voice of God.

Bewildering Urges, Pious Choices

For the sake of argument, let’s grant that, for one or two percent of the population, homosexuality is inborn. But others may likewise be tormented by bewildering urges to necrophilia or incest; some men might claim a genetic predisposition to philandering. Before we validate any sexual activity, we need to ask if it’s healthy and helpful.

The National Gay and Lesbian Task Force envisions teenagers feeling their inborn homosexual tendencies emerge, and needing support for “coming out.” NAMBLA eagerly agrees. Paul Mulshine spells out the result: “Through December 1993, 7,015 gay males below the age of 24 had contracted AIDS. Given the latency period of AIDS, all but a handful of these boys must have been infected while they were still below the age of consent, almost certainly by adult gays who were helping them find their identity as homosexuals . . . they didn’t get it from their fellow teenagers.” No wonder society hesitates to condone homosexual behavior.

Those who struggle with such passions need our prayers. For some, persistence and prayer will lead to reorientation, while for others, there will be the difficult lifelong discipline of celibacy. As tough as this sounds, it’s not impossible, and it’s not unusual. Christianity has always required celibacy of unmarried heterosexual believers, which all of us were at some point and many of us may be again. This isn’t something we demand of homosexuals without being willing to shoulder the burden ourselves. On the path of celibacy homosexuals will find a crowd of heterosexuals going back two thousand years: never-married Christians, those widowed or divorced, those caring for seriously ill spouses. We know it’s tough, and we know where to find help: sixteen hundred years ago St. John Chrysostom wrote, “Even if lust makes imperious demands, if you occupy its territory with the fear of God, you have stayed its frenzy.”

The final issue is not inborn urges but behavior. Passions may not be chosen, but actions are.

A Strange Texture

Back when I was going to speak at the pro-life homosexuals’ meeting, one of my friends tried to talk me out of going. He said that homosexuality wasn’t like other heterosexual sins. Heterosexuality in all its sinful forms—adultery, fornication, and the rest—is finally natural. Homosexuality is unnatural. It’s therefore a different order of sin, and much more depraved.

While he didn’t convince me, I must grant that homosexual sin does have a different texture. When I was in college, in my pre-Christian days, I had many homosexual friends, and one of the things that continually puzzled me was how cruel they could be to each other. There was a level of malice that didn’t obtain even among the most spiteful residents of the girls’ dorm.

Worse, there was a relishing of ugliness, degradation, and perversion that made no sense to me. I asked one once, “Why are you guys so nuts about Judy Garland, anyway?” He replied with a gleam in his eye, “Because she had everything, and she lost it all.” They didn’t love her freshness, American-girl wholesomeness, her bright eyes and astonishing voice. They loved her slow, miserable suicide.

When I’d ask, “Why do you guys love meanness so much?” I’d get a complicated answer. It’s a reaction against being loathed by society, they’d say. We are scorned and despised; we provoke disgust. It’s a hard thing to know that you disgust people. Somehow a blend of self-hatred and lust begins to take pleasure in that perception of foulness. It gets an edge of defiance, of secret nasty pride. And at the same time, a river of self-loathing and self-destructiveness runs underground through it all.

In our own twisted hearts I believe we can understand this. Awful and sad as it is, it has a sick logic. There is nothing to do for it but to feel pity, and beg God for mercy and healing.

Despair and Self-Destruction

Part of what makes the texture of homosexuality different, then, is this impulse toward degradation. In a Village Voice article titled “Why Gay Men are Having Risky Sex,” Michael Warner thoughtfully turns over this inclination.

He is perplexed at the statistics: Thirty to thirty-eight percent of HIV-negative gay men admit they don’t always use condoms. In San Francisco, rates of new infection have nearly quadrupled since 1987. This is not the result of ignorance; pro-condom messages have saturated the culture. Warner quotes one activist: “Everybody’s grandmother knows about anal sex and condoms.”

The strategy ever since 1983 has been, he says, “Get the information out and make it attractive. But over and over I hear the same thing from prevention workers: information alone is no longer doing the job.” Then Warner found that it wasn’t doing the job for him either. “When I had an unsafe encounter last winter, I spooked myself blank.”

Over the course of a long article Warner tries to sort this out. Why did he—why do so many homosexual men—risk their lives when they know better? Why isn’t it enough just to tell people the right thing to do?

Some will recognize this as an ancient theological question posed in Romans 7. But Warner writes from a world that has no history before the Stonewall riots that began the modern gay rights movement, and has no resources beyond its own wit, passion, and fading beauty. “In the vast industry of AIDS education and prevention, I knew of nothing that would help me answer this question.” Warner writes in the Village Voice, a tabloid weekly whose back pages are tiled with tiny ads offering every imaginable sexual vice, and some unimaginable ones. His article is surrounded with vanity ads for body piercing, hair weaving, muscle gyms, and spiritual candy (“Enjoy a past life regression, $39”). In this confused and rootless space, Warner tries to fathom the source of human self-destruction.

He comes up with several answers: the generalized despair of the homosexual life, the thrill of taunting death (“no sublimity without danger”), the weariness of a constantly monitored sex life, and the use of drugs to silence that monitor. There is the deadly variation on “If you loved me you would . . .”, this time ending, “trust me when I tell you I’m not sick.”

Envy & the Appeal of Violation

Warner also reports a sad, surprising phenomenon: healthy homosexuals can feel envy for the enhanced identity of the HIV-positive homosexual. These people do not necessarily appear sick; they may be asymptomatic for many years (when Warner looked up his impulse-partner, he found the man had died of AIDS “only a month after I last saw him, healthy and beautiful as ever”). HIV-positive men are members of a privileged sub-society, those who can live as if there were no tomorrow. They have their own style, their own “mordant humor,” their own magazines like Diseased Pariah News. Homosexuals not lucky enough to have HIV may want to try on the identity, just this once.

But the most startling passage in Warner’s analysis is this: “The appeal of gay sex, for many, lies in its ability to violate the responsibilizing frames of good, right-thinking people.” Think about that: the very appeal of the sex is that it is bad, that it offends, that it’s wicked and disgusting. Warner goes on: “AIDS education, in contrast, often calls for people to affirm life and see sex as a healthy expression of self-esteem and respect for others. One campaign from the San Francisco AIDS Foundation urges men to treat sex the way you might buy municipal bonds: playing it safe, making a plan, and sticking to it. Most efforts to encourage us to take care of ourselves through safer sex also invite us to pretend that our only desire is to be proper and good.”

Christian heterosexuals can resonate with that; we’re used to being told that sex in marriage is a blessing, a delight, a way to “affirm life” as Warner says and express tender love. But that isn’t what homosexuality is all about. Warner says, in perhaps his most startling admission, “Abjection continues to be our dirty secret.”

His conclusion is that “the emphasis on self-esteem . . . may be counter-productive.” Attaching positive messages to the safe-sex creed may actually cause homosexuals to be less likely to accept it. They are refusing to use condoms precisely because they’ve been told it’s the right thing to do. Being good runs counter to their culture.

Warner wrote of his risky encounter, “I recoiled so much from what I had done that it seemed to be not my choice at all. A mystery, I thought. A monster did it.” This is a scary monster indeed, but a similar monster lurks in every human heart, unrelated to sexual orientation. This is the monster that every faith and every worldview based on “the basic goodness of humanity” underestimates with deadly regularity. Sometimes goodness isn’t what we want. By the grace of God, our pet sins may not be acted out with such bizarre vulgarity, but they all deserve the same wages. We don’t need self-esteem, we need a savior. All of us.

The Savior of Us All

Who will bring the Savior to our gay and lesbian brothers and sisters? The very idea is so fraught with complicating factors—perceptions of judgmentalism and being patronizing, the politicization and defiance of the gay rights movement—that we scarcely know how to begin. But if we can bring ourselves to see them, they are no longer “the brother whom we have not seen.” At that point we can bring ourselves to love them. And with patience, the words of salvation can be shared.

I volunteer with a ministry that visits AIDS patients; another woman and I go down the hallway in a secular, low-cost nursing home in the heart of Baltimore, handing out apples and peaches and asking patients if they’d like us to pray with them. Together we work our way through visits to forty or fifty patients, a large black Baptist lady and a short white Orthodox lady, each with a plastic grocery bag full of fruit.

Gary Carr, the man who first introduced me to Love & Action AIDS visitation ministry, told me why he does it. “When people are facing eternity, when they’re at the crossroads, they’re willing to listen,” he says. “I go, primarily, because it affords an opportunity to share Jesus Christ, the living hope. Social programs are just that—a band-aid on a flood. With the gospel I’m able to present Christ to an individual who needs to hear that there is hope.” Gary helped me get over my us-and-them thinking about gays, and begin to see them as sinners in need of a merciful God, just like me.

Misplaced Cowboys & a Misfit Friend

It’s not the view that comes naturally to everyone on our side of the cultural fence. A while ago I spent a day at a conference in a Washington, D.C. hotel with about a hundred pro-family leaders, enjoying our numbers. But as the day went on, we began to be outnumbered by cowboys. Cowboys in the elevators, cowboys in the halls, cowboys sitting at tiny glass tables in the lounge. Two things about this seemed unusual: first, Washington, D.C. is not a kind of town for cowboys. And second, something about the cowboys themselves seemed out of synch. I always imagined cowboys to have a sprawling presence scaled for endless plains, a physical expansiveness unrelated to body size. Cowboys might appear awkward under a roof, perhaps charmingly bashful, but never brittle or edgy.

These cowboys didn’t fit my image. They were nervous. Their presence was, if anything, smaller than average, more compressed and self-protective. I stood near one waiting at the elevator bank: perfect black boots, jeans aged carefully as wine, and above the black mustache eyes darting sidewise furtively.

The mystery became clear when I examined the sign over their registration table: Atlantic States Gay Rodeo Association. Back in our meeting room, whispers went hissing by: “All those cowboys—they’re homos!” Someone snickered. Someone said, “Maybe we should pray for them.” Another grumped, “Next time, we ought to find out who else is going to be in our hotel.” But I was thinking about Geoffrey.

Geoffrey was one of my friends during my pagan college days; I still remember his large, lightbulb-head topped with sparse blond hair, his invisible blond mustache, the compressed and awkward way he carried his large frame. His skin was pale as cellar vines, and his eyes pale as water, barely blue. Geoffrey was from a hard-scrabble Southern town called Ulmer. Geoffrey was a genius. Geoffrey was gay.

One night Geoffrey and I sat under a tree in the women’s quad and he asked me, nervously, if it showed that he was gay. No, I lied. He wasn’t effeminate, but he was jittery, arch, and unhappy. Behind his nervous laugh, woundedness flowed out of him like a stream.

Too-clever Geoffrey had been misunderstood in Ulmer. He grew up dirt-poor, brushing flies away from the peaches at a roadside stand, while reading all eleven volumes of the Durants’ Story of Civilization. At home he listened to the symphony crackling over the radio from the big city, the county seat. He taught himself some Bach on the piano.

“That boy has no common sense,” neighbors said. But Geoffrey had plenty of other kinds of sense: on one of his history papers, the professor had written, “I really am not capable of grading this.” He ended up going into classical studies, spending Sundays in the library with moldering leather volumes of ancient Greek and Latin.

One quiet evening, in a tentatively self-revealing mood, he told me about the loneliness of the gay life. He described the previous weekend’s after-hours session at Midge’s gay bar. Every Friday after midnight the doors were closed to give the guys a chance to be alone together, to dress up and stand in the spotlight, lip-synching to scratchy records.

The previous Friday, Geoffrey said, a chubby guy had taken the microphone and stood alone to sing along with West Side Story. “There’s a place for us, somewhere a place for us,” he silently mouthed, behind the female singer’s soaring voice. “Someday, somehow, we’ll find a new way of living. We’ll find a way of forgiving, somewhere.”

By the time he finished, everyone was crying. “That’s what it’s like,” Geoffrey said. “There’s no place for us. We never fit in. We don’t belong anywhere. All we have is this few hours in a crummy dive on Friday night. Mostly, we’re alone.”

An Irretrievable Gift

Geoffrey gave me the best gift of my life: he introduced me to Gary, my husband now for twenty-two years. We planned that, at our wedding out in the woods, Geoffrey would walk before us in the procession. But a month before that date Geoffrey was driving alone down a two-lane North Carolina road. Just outside Rockingham he drifted into the oncoming lane, swerved back to avoid hitting another car, and flipped over into a ditch. He was killed instantly.

Now he is gone, lost forever. Weeds long ago swarmed over the gravel on an Ulmer grave. I will never see him again. Outside an extraordinary and inexplicable extension of God’s grace, I have no reason to hope that Geoffrey was saved. He died just before noon on a warm Good Friday. As far as I can know, he will never see Easter morning.

The sad, nervous cowboys shuffled near us all weekend; we passed by them as Christians, destined for eternity, destined to live for the praise of God’s glory. We found them frightening, or humorous, or loathsome. They didn’t find us at all.

One of Geoffrey’s favorite quotes was a line from the French poet Paul Valery: Dieu a tout fait de rien, mais le rien perce. I was flippant and cynical and loved it. On a lark I embroidered it as a gift for him, flowing letters festooned with flowers. “God made everything out of nothing, but the nothing still shows through.” That was the only thing I ever told Geoffrey about God.

Frederica Mathewes-Green is a columnist for Beliefnet.com and a contributor to the Christian Millennial History Project multi-volume series. Her books include At the Corner of East and Now (Putnam), The Illumined Heart (Paraclete Press), and The Open Door: Entering the Sanctuary of Icons and Prayer (Paraclete Press). She lives in Linthicum, Maryland, with her husband Fr. Gregory, pastor of Holy Cross Orthodox Church. They have three children and three grandchildren.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on sex from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor