Reforming Worship

Reverence, the Reformed Tradition, & the Crisis of Protestant Worship

by D. G. Hart

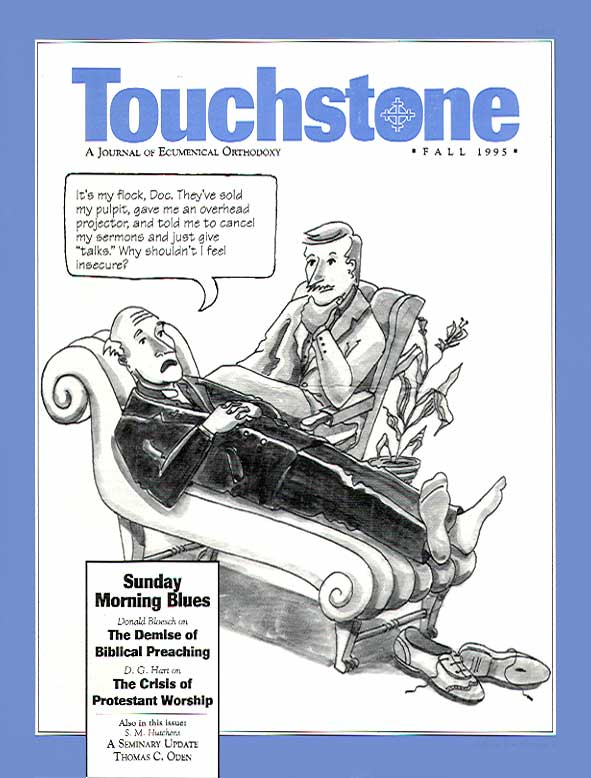

Within evangelical circles the clergy and laity alike are giving great attention to worship. Should congregations sing “praise songs” (complete with overhead projectors and guitars) or should trained choirs (complete with robes and pipe organ) sing the great works of sacred music? Should services be updated to become user-friendly, accessible for the unchurched, or should they continue in traditional patterns even if bewildering to visitors? Should the minister be the only leader of the service or may the laity also lead worship, whether in prayers or song? In a culture that finds talking heads boring, should the thirty-five minute sermon continue to be the central element of worship or should congregations be open to less verbal forms of communication such as liturgical dance and drama? These are questions that bedevil not just evangelicals but also Presbyterian and Reformed congregations in North America and increasingly throughout the world.

Frustrated by what they perceive as the shallowness and emptiness of much contemporary worship, some conservatives have left evangelical and Reformed communions for the Episcopal Church as well as the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church. These people are fed up with worship that according to one critic is “a personalized, subjective, make-it-up-as-you-go-along affair.” No one can agree what worship is. “Is it banging a tambourine, participating in evangelism, prayer, singing, speaking in tongues—what?”

What is curious about the contemporary discontent over worship is that the paths of those leaving for Canterbury, Rome, and Constantinople never go through Geneva. Yet Reformed worship has not been hospitable to the subjectivism, individualism, or banality that these pilgrims are fleeing. Evelyn Underhill, in her book, Worship (1937), described John Calvin’s worship as an “austere Puritanism” that “utterly concentrated on the Eternal God in His unseen majesty” and “has a splendour and spiritual value of its own.” Reformed worship, Underhill continued, was “a powerful corrective of humanistic piety; driving home the abiding truth of God’s unique reality and total demand, and man’s poverty, dependence, and obligation.” This would appear to be a welcome corrective to the man-centered, therapeutic spirit that characterizes so many worship services today.

So then, why aren’t more of the critics of evangelical worship dusting off copies of Calvin’s Ecclesiastical Ordinances and the Genevan Psalter? Underhill’s description of Calvin’s worship provides clues for an answer.

No organ or choir was permitted in his churches: no color, nor ornament but a table of the Ten Commandments on the wall. No ceremonial acts or gestures were permitted. No hymns were sung but those derived from a Biblical source.

People looking for elaborate liturgy, heightened experience and high drama, find little appeal in Reformed worship. The Reformed tradition stripped worship bare, critics argue, denying the human elements of worship, and left Presbyterians with no liturgy, no ritual, and hence, no room for a sacramental presence in worship.

Yet, this criticism of Reformed worship, which many contemporary Calvinists would probably second, misunderstands liturgy and sacrament. After all, every church has a liturgy whether its members think of themselves as liturgical or not. Liturgy is merely the form and order of worship. Both the highest Anglo-Catholic Mass and the lowest evangelical “praise and worship” service are liturgical in the narrowest sense of that word. Obviously, they differ dramatically in liturgy. But both embody a form and order of worship. Even Underhill, who criticized Calvin, recognized the liturgical character of Reformed worship: “the bleak interior of the real Calvinist church is itself sacramental: a witness to the inadequacy of the human over against the Divine.”

From a different perspective, then, Reformed worship may be one of the highest or most churchly forms of worship. For Calvin strove to make every aspect of the service, from the design of the church’s interior to the manner of song, conform to the character and grace of the God who revealed himself in Christ and the Scriptures. In fact, Calvin’s theology and understanding of worship seem to fit together and reinforce each other so well that one wonders how people in the Reformed tradition could possibly want or consistently try to maintain Calvinist theology without also enthusiastically embracing the elements and character of Reformed worship as formulated and practiced in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Calvin and Worship

An axiom of John Calvin’s theology was the importance and centrality of worship for vital and genuine Christian faith and practice. In fact, Calvin put worship ahead of salvation in his list of the two most important facets of biblical religion. The Christian religion maintains its truth, he wrote, by “a knowledge, first, of the mode in which God is duly worshipped; and secondly, of the source from which salvation is to be obtained.”

Calvin also observed that the first table of the law—the first four commandments—all directly related to worship, thus making worship “the first foundation of righteousness.”

The prominence of worship led to Calvin’s articulation of his regulative principle, one of the hallmarks of the Reformed tradition. The regulative principle teaches that public worship is governed by God’s revelation in his Holy Word; whatever elements comprise corporate worship must be directly commanded by God in Scripture. The fact that a congregation always has worshipped in a particular way or that a certain practice stems from sincere piety are insufficient justifications for such worship. According to Calvin, God not only “regards as fruitless, but also plainly abominates” whatever does not conform to his revealed will. “The words of God are clear and distinct,” Calvin wrote, “‘Obedience is better than sacrifice.’ ‘In vain do they worship me, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men, . . . .’ (1 Sam. 15:22; Matt. 15:9).”

Not only did the desire to obey God inform Calvin’s conception of the regulative principle, but equally important was his understanding of human depravity. The principal effect of Adam’s first transgression was to turn all people into idolaters. All individuals, Calvin believed, possess a seed of religion or a sense of God in their souls. But after the fall this religious sense no longer led to the true God but forced men and women to create gods of their own making, ones that conformed to their own selfishness and vanity. The temptation of idolatry required Christians to be ever vigilant in regulating their worship by the direct commands of God in Scripture. This temptation made Calvin especially suspicious of practices in worship that were said to be pleasing or attractive to members of the congregation. He said, the more a practice “delights human nature, the more it is to be suspected by believers.”

Calvin’s theology of worship required reforms of the Roman Catholic practices that he encountered in Geneva. But the need for reform did not mean the abandonment of liturgy nor did it require the elimination of all elements of the Catholic liturgy. The Reformers purified the practices of their day; they transformed the theological and spiritual content of Christian worship, but they did not create a new order of worship out of nothing. Instead they altered the elements of worship to conform to the theology of the Reformation. Calvin’s liturgy in Geneva, for instance, demonstrates continuity with the past while also reflecting changes derived from new insights into God’s revelation. The order of worship was basically as follows:

Invocation

Confession of Sins

Prayer for Pardon

Singing of a Psalm

Prayer for Illumination

Lessons from Scripture

Sermon

Collection of Offerings

Prayers of Intercession

Apostles’ Creed (sung while elements of Lord’s Supper are prepared)

Words of Institution

Instruction and Exhortation

Communion (while a psalm is sung or Scripture read)

Prayer of Thanksgiving

Benediction

Even though Calvin followed a regular pattern in his worship services he did not believe it was possible to prescribe all matters of worship. He acknowledged that there were incidental matters that Scripture did not determine. In such matters churches had freedom under the general guidelines of the Bible to implement practices that would honor God and edify his people. While the regulative principle teaches that a specific practice must be commanded by God’s Word, it also guarantees freedom in areas where Scripture is not explicit.

Principles of Reformed Worship

While Calvin and other Reformers hesitated to prescribe a specific liturgy for all churches, remarkable agreement existed among Presbyterian and Reformed churches about the nature and manner of worship throughout Western Europe from the sixteenth century until well into the eighteenth century. Indeed, the directions for worship crafted by Reformed churches from Calvin up through the Westminster Assembly suggest five principles that should govern worship in the Reformed tradition.

The first is the centrality of the Word of God. God’s Word not only directs the form or manner of worship but also comprises the content of worship. It is read, sung, seen (in the Lord’s Supper), and preached. The centrality of God’s Word is especially evident in the Reformed emphasis on preaching. In contrast to Roman Catholic worship where the focus is the Mass and the altar is the centerpiece of church architecture, the Reformers made preaching the central part of the service and put the pulpit on the center of the sanctuary.

A second principle of Reformed theology, very much related to the first, is that worship is theocentric. Worship is God-centered and its aim must be the glory of God. It is the highest form of fellowship between God and his people and must be done in spirit and truth. There is nothing that God hates more than false worship. Worship is absolutely necessary to Christian faith and practice because God commands it and has so constituted us that worship is essential to the strengthening of our spiritual life.

This means that worship is not designed for evangelism. The fact that services on the Lord’s Day have become “seeker sensitive” shows a perversion of the nature of worship. Corporate worship is for God’s people for it is only his people that may worship him in spirit and truth. Non-Christians may be welcomed and should be encouraged to hear the preaching of the Word, which the Westminster Shorter Catechism describes as being an “especially” effectual means of “converting and convincing sinners.” Yet, the means by which God brings people to himself should not cause us to miss the nature of worship. If we incorporate evangelism into our worship it is only a sign of laziness, not an indication that church growth experts are right. Evangelistic services have their place and the Church needs to take to heart the Great Commission. But discipleship is also part of Christ’s instructions to his disciples and worship is one of the principal means by which “the benefits of Christ’s redemption” are applied to us.

The dialogical character of God’s meeting with his people is the third principle governing Reformed worship. Corporate or public worship is the meeting of God with his people. Believers come at his invitation and are welcomed into his presence. God speaks through the invocation, the reading of the Word, the sermon and the benediction. Worshippers respond in song, prayer, and confession of faith.

The dialogical character of worship raises the much-debated issue of feelings or emotions in worship. To many outsiders and to many spokesmen for young people in Reformed churches (teenagers often show a better understanding of worship than their parents), worship appears to be boring and repressive. Many want the Church to be more open, expressive, and emotional. Yet, what some of these critics fail to understand is that God has told us in his Word how we should respond to him. In worship we answer God through song, prayer, and confession of faith. For some, however, this does not seem to be an appropriate vehicle for response. They would rather respond to God in the same way they respond to or participate in a rock concert, a baseball game, or a performance by an orchestra.

To note the affinity between modern entertainment and contemporary worship is to pinpoint one of the sources of misunderstanding in much current thinking about worship. For there is a vast difference between responding to entertainment and hearing and submitting to God’s Word. Yet, this point is lost on many members of worship committees in numerous Presbyterian and Reformed congregations.

Many individuals come to a service expecting to express personal emotions and affections as part of their response to God. What they fail to recognize is that worship in the Church is corporate and, therefore, should be appropriate for what a people may do as a body or group. The Westminster Directory for Public Worship crafted by the Westminster Divines, is just that, a guide for public or corporate worship. In our houses of worship we worship as a people, not as individuals.

An analogy that may help explain this is the relationship between a father and his children. A son may express himself one way to his dad when they are alone together. There is a chance to be more intimate and expressive. But when the same son, along with his two brothers and two sisters, is in the presence of his father, he will generally not demonstrate the same level of intimacy or affection, or reveal to the same degree the nature of his relationship with his father as when they are alone together. It would be rude, for example, for that son to expect to sit on his father’s lap if that display of affection suggested favoritism or became a barrier to the other siblings’ communication and fellowship with their father. Yet, this is virtually what happens when some members of a congregation want their personal feelings to be incorporated in worship.

The fourth principle of Reformed worship is simplicity. The fuller revelation of God in Christ in the New Covenant means that Christians are not dependent on the childish and fleshly elements of the Old Covenant. Because of the work of Christ believers already sit with him in glory when they gather for worship. This aspect of Christ’s work greatly diminishes the church’s need for visible or material supports in worship. Simplicity in worship, therefore, is closely related to spirituality. In the New Covenant, according to Reformed theology, God is more fully present with his people than in the Old Covenant. But this presence is spiritual, not physical. Christ’s command that his followers worship him in spirit and truth is consonant with the new arrangement between God and his people.

Simplicity also suggests routine. So often contemporary evangelical worship services are packaged and rehearsed in an effort to manipulate the congregation into a worship experience, as if the different elements of worship were designed to arouse feelings or emotions that are somehow more intimate and more expressive of communion with God. In other words, many contemporary worship services call attention to the service and worship leaders. Many such services are designed by people who think themselves devout and believe that if the congregation follows their example the congregation will also have an intimate experience with God (they are even called “worship modelers”).

In contrast, Reformed worship maintains that worship should not be novel or creative. Rather it should be routine, ordinary, and habitual. C. S. Lewis, no Reformed theologian, nevertheless made a point supported by the Reformed tradition when he said that a worship service “works best when, through long familiarity, we don’t have to think about it.” “The perfect church service,” he added, “would be the one we were almost unaware of; our attention would have been on God.”

But every novelty prevents this. It fixes our attention on the service itself; and thinking about worship is a different thing from worshipping. . . . “‘Tis mad idolatry that makes the service greater than the god.” A still worse thing may happen. Novelty may fix our attention not even on the service but on the celebrant. . . . There is really some excuse for the man who said, “I wish they’d remember that the charge to Peter was ‘Feed my sheep’; not ‘Try experiments on my rats’, or even ‘Teach my performing dogs new tricks.’”

The fifth and final, and perhaps the most important, principle of Reformed worship is reverence. According to Calvin “pure and real religion” manifested itself through “faith so joined with an earnest fear of God that this fear also embraces willing reverence.” Worship should be dignified and reverent but it does not achieve these qualities through elaborate ceremonies or complex liturgies. In fact, Calvin believed that “wherever there is great ostentation in ceremonies, sincerity of heart is rare indeed.”

This does not mean that worship has no room for joy or emotion as some critics of Reformed worship have charged. Joy, along with a full range of emotions—i.e., grief, anger, desire, hope, and fear—should be a part of worship. But the need for reverence and decorum dictates that any expression of emotion in worship should be tempered by moderation and self-control. And to ensure that every aspect of worship is done decently and in good order the Reformed tradition has insisted that every service be supervised by the elders, who bear responsibility for corporate worship, and that the minister, who speaks for God and for God’s people, lead and direct the service.

A helpful way to understand reverence may be to think of the ethos of a funeral service for a professing Christian (even though the Westminster Divines disapproved of funeral services). There we contemplate the death of a loved one and are filled with sadness and are reminded of our own frailty. Yet, when the deceased is a believer the service also is an occasion for joy because we believe that God has called one of his children to be with him, and that the believer has been “made perfect in holiness” and has “passed immediately into glory.”

Why should a worship service be any different? For in our services the death of our Lord is central. Of course, we do not stop with Christ’s death. We go on to rejoice at his resurrection, without which, the apostle says, we would not have hope. Still, the joy we experience in contemplating and worshipping our risen Savior is an emotion that always is tinged with gravity and humility. It is not the joy of a party celebrating the national championship of a college football team. It is a joy that not only recognizes the suffering and death of Jesus Christ, but also recognizes our own complicity, because of our sin, in his pain and ignominious death.

The Revisionist Impulse

Patterns of and ideas about worship have remained fairly constant within Reformed and Presbyterian practice, but within the last twenty years the theology and practice of Reformed worship has been stretched to the limits. Various communions have tried to revise directories for worship, while countless congregations have established worship committees whose sole function seems to be modernizing worship. While in some cases the proposed changes are informed by sound biblical and Reformed insights, they also expose genuine discontent within the Reformed household about worship. This discontent probably was summarized best in a recent report to one conservative Presbyterian denomination:

There is widespread dissatisfaction or at least widespread lack of use in the church of the present Directory. There are parts of the present Directory that are so dated (e.g., “the stately rhythm of the choral”) that there must be a rather thorough revision. Yet there is no consensus of where the church wants to go in worship. The current situation in the church regarding worship is diverse from near liturgical anarchy to others who feel that singing uninspired hymns is a violation of the regulative principle.

How did this state of affairs come to be? Some might point to new biblical insights that show that the old habits of worship and the theology that undergirded them were too bound to a specific form of cultural expression rather than the teaching of the Word of God. Others cite the limited growth of churches that don’t change their worship and the inability of traditional worship to appeal to Christian youth as facts that demand that worship be made relevant and free from older and supposedly human patterns of worship. Others see this discontent and the changes within worship as clear indications of defection from the Reformed theology of worship.

Many of the changes in thinking about worship over the last twenty-five years stem from significant transformations within American culture. Old ways of worship no longer seem plausible; they appear to be ineffective if not alien. The effective ministry of the Church, some argue, requires that it keep pace in contextualizing the gospel to make it understandable to contemporary culture. And if this means abandoning a manner of worship that dates from the 1930s, so be it. As long as the content of worship is sound, the form really doesn’t matter. So the changes in worship are merely alterations of form, dropping the style of the 1930s for the culture of the 1990s.

It is ironic that believers can be so uncritical of contemporary cultural expressions—and therefore think that the style of the 1990s is a fitting one for worship—when the same believers are so alarmed by the evils of this culture. (It also is remarkable how Calvinists who insist that everything be done for God’s glory so often judge worship on the basis of whether it is pleasing to men, women, and especially teenagers.)

Most Christians would agree that the people of God face difficult times. The Church is challenged by unjust policies of the government, by the moral relativism of public schools, and the decadence of the media. Yet, few seem to recognize the subtler dangers of American culture. One of the most insidious and subtle influences upon the Church comes from the media and the entertainment industry. Ministers often preach about the overt dangers of Hollywood, warning about the sex, violence, and disrespect for religion in many movies, TV shows, and popular songs. A far more dangerous influence, however, is the way popular culture has altered attitudes toward worship.

Popular culture has fostered a significant shift in perceptions about corporate worship. Christians increasingly exhibit a willingness to regard their time together collectively in the same way that they think about public forms of entertainment. Worship becomes a performance for the congregation. Gone is the conviction that the audience for worship is not the congregation but God himself.

Even more alarming is the way popular culture has nurtured an ethos of informality, breaking down distinctions between what is solemn and what is disrespectful. Older worship seems out of date—the phrase “the stately rhythm of the choral” doesn’t make sense—because our culture scorns or has no use for what is dignified and majestic. What makes contemporary or popular forms of worship objectionable from a Reformed perspective is not that they are low brow, though the prayers, praise, and music of today’s worship are often trivial. Believers can worship God whether or not they appreciate a sonata by Mozart or a sculpture by Michelangelo. Rather, the problem of much contemporary worship is that it does not acknowledge the insight of Calvinism, namely, that people, including Christians, are constantly tempted to fashion God in their own image. Worship reflects a people’s conception of God. Many of the innovations today in worship convey an erroneous picture of God. Worship is a statement of theological conviction about who God is and who we are as his covenant people.

A Matter of Reverence

Reformed theology always has held that when believers gather on the Lord’s Day their practices should reflect humility and reverence. Here Christians come before the Holy and Transcendent One, who is the righteous Judge of the universe, whom men and women offend daily, and who has wonderfully provided a way of salvation through his Son Jesus Christ. Worship should be a reminder of the gulf between God and sinners and of what God has done to overcome that gulf, lest believers lapse into a false understanding of God. In worship Christians profess and honor the character of the God whose presence they enter and who has brought them out of an estate of sin and misery. Worship, then, is not something done lightly or without serious consideration.

The forms and style of contemporary culture cannot contain the dignity and respect that should characterize the external and internal posture of Christians as they approach God’s throne. Though there is therapeutic appeal in thinking of worship as entering a pub where God serves as a barroom buddy, always ready to hear what we have to say and to wipe up our tears and spills, the God revealed in Scripture is a King who sits erect upon the throne of glory, attentive to the words, thoughts, and emotions of his subjects as they assemble before him.

To be sure, that King is also our Father, but in the light of what the fifth commandment and the Apostle Paul say about the respect and fear children should have for parents, the image of God as our father does not allow for nonchalance or frivolity in worship. The worship recommended and practiced by Calvin, Knox, and the Westminster Divines, reflected a reverent combination of joy and fear. And that older manner of worship always was restrained by the sense that any display of flippancy and disrespect would offend God.

Rather than following the liberationist and irreverent impulses of American culture, Calvinists, if they are to have anything to say to the contemporary discussions about worship, need to recover in their theology and practice of worship what Psalm 2:11 talks about when it says God’s people should “rejoice with trembling.” There are no better verses to characterize Reformed worship than Hebrews 12:28–29. “Since we are receiving a kingdom that cannot be shaken, let us be thankful, and so worship God acceptably with reverence and awe, for our God is a consuming fire.”

This insight has characterized Reformed and Presbyterian worship since the Reformation. One wonders how Reformed churches can meaningfully retain their theological heritage while abandoning the essence of Reformed worship, especially since weekly worship provides the foundation for and reinforces the very theology that Reformed believers confess. But at least the abandonment of Reformed worship may explain why those who look for a service with dignity and reverence so often turn to non-Reformed communions.

If Reformed churches are going to be true to their theology and offer to weary souls some rest from the shallowness and banality of contemporary evangelical worship, they need to recover the liturgy and theology of worship of the Reformed tradition, a worship that took seriously the notion that God is indeed “a consuming fire.”

D. G. Hart is Librarian and Associate Professor of Church History and Theological Bibliography at Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His article “Whatever Happened to Office? Ordination and the Crisis of Leadership in American Protestantism” was published in the Summer 1993 issue of Touchstone.

D. G. Hart works for the Intercollegiate Studies Institute (www.isi.org) and is an elder in the Orthodox Presbyterian Church. He is the author of A Studen't Guide to Religious Studies (ISI Books) and John Williamson Nevin: High Church Calvinist (P&R Books).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on protestant from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor