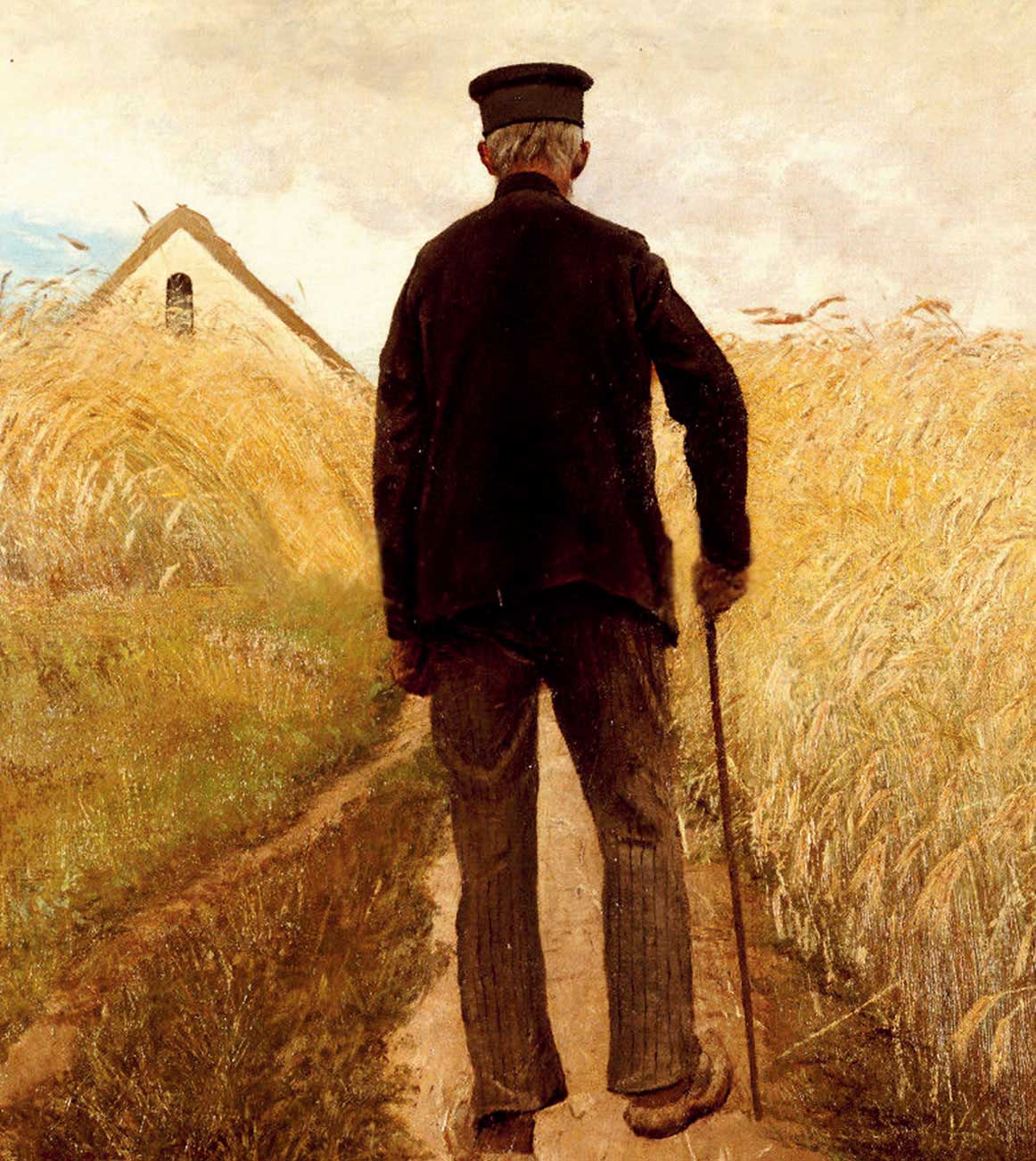

A Stick Becomes the Staff of God

Reflections on Faithfulness in the Ordinary & the Routine

by Denis D. Haack

The seven sons of Sceva, we’re told in Acts 19, attempted an exorcism only to be cast out themselves. Impressed with the Holy Spirit’s empowering of the apostles, they tried to get in on some of the action. “In the name of Jesus, whom Paul preaches,” they would say to the evil spirits, “I command you to come out” (v. 13). We aren’t told whether that formula was ever successful, but one day it backfired. They found some poor demon-possessed soul over whom they recited their incantation, but instead of fleeing the demon talked back. “Jesus I know, and I know about Paul,” the evil spirit replied, “but who are you?” (v. 15). And the man whom they were trying to help leaped into action, thrashing all seven of them. “He gave them such a beating,” Luke records, “that they ran out of the house naked and bleeding” (v. 16).

It is a testimony to the ministry of Paul that the demons should know him by name. It is not surprising, of course, that they would know of Jesus—they knew that Name and trembled (James 2:19). But they knew of Paul, too, for in him the Spirit of Jesus dwelled. Think of it: To Be Known in Hell. Can one imagine a better tribute to the servant of God?

“God did extraordinary miracles through Paul,” Luke reports (19:11). I dream of extraordinary things, of course, of things spectacular enough that the blessing of God is palpable and sure. The extraordinary is not, however, what my life consists of. It is filled, instead, with very ordinary things. Just once it would be nice to do something and sense that as a result the kingdom lurched forward quite remarkably.

Os Guinness says that our faithfulness, our “action can cause ripples that never cease,” and that’s good as far as it goes.1 But ripples are tiresome little things of uncertain impact. Is that all my hard-won faithfulness and struggle and effort will produce—for an extraordinary ripple.

The Seduction of the Extraordinary

Our primary calling as the children of God is to be faithful in the ordinary and the routine. It is pride that makes us lust after the spectacular and the extraordinary. The ordinary that is before us moment by moment is not to be despised or considered insignificant or secondary. It is to be embraced and celebrated as the sphere for which we were made and in which the grace of God is so spectacularly at work.

My dictionary defines ordinary: “adj., 1. customary, usual, regular, normal. 2. familiar, unexceptional.”2 Not exciting, but then there’s something reassuring about what is familiar. In general, though, most of us prefer the extraordinary. We dream of going beyond, of achieving something that is remarkable. Somehow, such things seem more significant. With the ordinary I have to believe that God is pleased; with the extraordinary I can see it. And so, all around us are believers seeking something from God to reassure them of his pleasure—a leading, a fleece, a gift, or a sign. The details may differ depending on temperament and ecclesiastical tradition, but the yearning is unmistakable. We dream of the extraordinary and mistakenly imagine it is where significance dwells.

In Faith and Its Counterfeits theologian Donald Bloesch warns that a mistaken understanding of heroism infects the church.3 The source of the virus is in Greek thought, he says, and the carrier is the wider culture. “In Greek popular religion,” Bloesch writes, “heroes were individuals of courage and wisdom who had been elevated to the status of demigods.” The heroic was linked to notions of “greatness” which was defined, in turn, as “transcending the ordinary by aiming for the highest, even at considerable risk.”4

Some in the early church, Bloesch argues, enamored with the extraordinary, synthesized the Greek hero with the biblical saint and introduced a mistaken idea that still plagues us. “A false notion of sainthood entered the church when it accommodated to the cult of the hero,” Bloesch says. “A saint became one who challenged and triumphed over the powers of darkness rather than a humble recipient of divine grace. Extraordinary feats of asceticism were prized over ordinary acts of loving-kindness and mercy.”5

The Reformers disputed this heroic view of sainthood, Bloesch says, but the idea remained entrenched in Western culture. “The Renaissance and Enlightenment,” Bloesch writes,

were receptive to the classical ideal, though an optimistic view of the heroic life came to prevail over the tragic outlook of classicism. In the liberal theology flowing out of the Enlightenment, the heroic ideal was reinterpreted as gaining mastery over nature or becoming a determiner of history.6

This does not suggest that God never calls his people to heroic greatness, nor that Christian martyrs should not be held in esteem. Bloesch is arguing instead that “sanctity is qualitatively distinct from heroism.”

Sanctity means nearness to God; heroism means defiance of fate. Sanctity is love of the unlovable; heroism is love of the ideal. Heroism aspires to heights bordering on the divine; sanctity means surrendering to the divine. Heroes have fame; saints have infamy. Heroism exalts what is noble over what is vulgar; sanctity upholds what is loving over what is hardhearted. Heroism regards humility with suspicion, but humility is the very essence of sanctity. The opposite of heroism is cowardice or timidity; the opposite of sanctity is prayerlessness.7

Christian faithfulness works itself out in the ordinary of everyday life, even though your ordinary may be far different from mine. I may even imagine your ordinary to be quite extraordinary, but I am not faithful unless content with the calling I have been given by God. “Sanctity may actually entail the sacrifice of greatness—a flight from heroism—should love so demand,” Bloesch concludes. “A disciple must be willing to follow Christ into obscurity.”8

Modernity is not kind to such notions. The activist mentality, “I am what I accomplish,”9 can seem natural whether the goal is our picture on the cover of Time or the cover of Christianity Today. The megachurch movement, evangelicalism’s breathless—and, unfortunately, largely mindless—embrace of modernity is hardly designed to choose obscurity over the heroic, or even to nurture believers who can recognize the difference.10

The Biblical View of the Ordinary

The Scriptures should cause us to see the ordinary in a very different light. In the Bible God reveals himself as one who transcends the ordinary but who has called us to be faithful in it and considers that very good. We transcend the ordinary by being in Christ, not by becoming heroes who specialize in extraordinary feats.

In Creation we learn that God made the ordinary and called it good. He formed creatures in his image from the dust of the earth to live in the world he had made and to serve him there. All that glorious creation became our ordinary. The calling he gave to our first parents was not extraordinary in the sense that only demigods could fulfill it but wonderfully realistic. They were to cultivate his world, treating it with tender care for it remained his. The ordinary and routine for Adam and Eve before the Fall only can be imagined now, but they were called to faithfulness in it not to an endless striving to transcend it.

This life could have continued, but that was not to be. Milton’s description of what transpired next remains unsurpassed:

. . . her rash hand in evil hour

Forth reaching to the Fruit, she plucked, she eat:

Earth felt the wound, and Nature from her seat

Sighing through all her works gave signs of woe,

That all was lost.11

Work was turned to toil with sweat and weeds, childbirth was filled with pain, and a serpent-crusher was promised. God’s glorious creation was made abnormal by the Fall, but the calling to faithfulness in the ordinary now fallen remained.

When the Redeemer appeared, he set about to restore the ordinary twisted so horribly by sin and the curse.12 In Mark 4:35–5:43, for example, the Scriptures record four episodes from the life of Christ. They may at first appear to be unrelated, but they are connected. The stories include, first, Jesus calming the storm after falling asleep in the boat (4:35–5:1); second, Jesus’ encounter with the demoniac named Legion (5:1–20); and finally the two intertwined stories of Jesus’ curing the woman who secretly touches his hem and his raising Jairus’s daughter from death (5:21–43).

In each of these stories three themes stand out. We see, first, something of the effects of the Fall. More specifically, the results of sin and the curse bring a loss of control. The disciples, some of whom were fishermen and thus capable of managing a boat, were overwhelmed by the storm and woke the Lord. “Teacher,” they asked him, “don’t you care if we drown?” (4:38). The demoniac’s friends had tried to bring him under control but couldn’t. They tried incarceration, but “no one could bind him anymore, not even with a chain” (5:3). The woman in the crowd had been ill for twelve years. When Luke tells her story he reports merely that “no one could heal her” (8:43). Mark wasn’t a physician and his comments are a bit more revealing. “She had suffered a great deal under the care of many doctors and had spent all she had,” he says, “yet instead of getting better she grew worse” (5:26). Like the storm that threatened the disciples and the uncontrollable Legion, the woman had no control over her disease. Jairus’s daughter died before Jesus could make it to Jairus’s home; the loss of control for the synagogue ruler was as absolute as a father can experience.

The second theme in these four stories is that in each case Jesus responds by bringing his grace into the situation. In the process he reveals that he is Lord of all. The wind and waves are stilled, the evil spirits are cast out, the sickness is healed, and the little girl is restored to life. Over each Jesus demonstrated that his word is sovereign. The people involved had lost control, and as a result been thrown into fear and hopelessness, but Jesus came, pushing back the effects of the Fall to bring redemption.

The third theme in these stories is that in each case Christ restored in people’s lives the ordinary that was twisted and perverted by the Fall. The incident of the storm doesn’t end with the disciples’ awestruck questions concerning Christ’s identity, even though the chapter break makes that appear to be the case. The story ends with them continuing across the lake (5:1), which was what they had set out to do in the first place (4:35). No mention is made of the details, but presumably it involved all sorts of ordinary things: bailing water, rowing, and working the sail if they had one. The ordinary and routine had been restored.

Legion, after being healed, wanted to go with Jesus, and “begged” permission to do so (5:18). Besides the obvious reason of wanting to be with the one who had freed him, imagine the team they could have made. Jesus could have preached the gospel of the kingdom, Legion could have given his testimony, the disciples could have been the advance team—modern managers of evangelism would have had a field day. But it was not to be. “Go home to your family,” the Lord told him (5:19). Go home where you belong and tell them about the grace of God. Nothing could be more ordinary and normal than that.

The woman pushed through the crowd and touched his cloak. She wanted anonymity but the Lord had other plans. Called upon to identify herself, the woman “came and fell at his feet and, trembling with fear, told him the whole truth” (5:34). The Lord, not content to bring only healing, gave her his peace as well. “Go in peace,” he told her, “and be freed from your suffering” (5:34). Could it be implied here that her “going” took her to the ordinary that had eluded her for twelve long years? No longer anemic, she would now have strength to do the things she had to forego for so long. And now after all that time, she was no longer ritually unclean, and could rejoin the people of God in the ordinary expressions of worship commanded in the Law.

And how does the story of Jairus’s daughter end? With her just being raised from death to life? It ends with a simple command from the Lord to the little girl’s parents: “Give her something to eat” (5:43). Few things are as everyday as preparing and serving food, and Christ’s command put the family back together in the ordinary and routine.

Perhaps we only recognize the wonder of the ordinary when it is taken from us and we lose control. When our oldest daughter was two years old she fell from an outdoor deck about 16 feet down onto a large rock. We were miles out in the country at a summer church camp I was directing. Carefully scooping her up, we raced into the nearest town only to discover the X-ray machine was broken. So, back-tracking, we drove to the city, praying desperately that our little girl would be all right. X-rays revealed a massive skull fracture, and the physician scheduled her for surgery. During those next few hours while we waited, filled with fear and grief and guilt, I realized that what I wanted most of all was the ordinary to be returned to us. We were praying for healing, of course, but our real desire, the real end of that healing would be the ordinary. Having our daughter “restored to health” meant having the ordinary restored—having her once again teasing the dog, pulling all the pots and pans out of the kitchen cabinets, and doing all the other things that she did each day. I realized that if an angel had appeared and said that revival would break out due to my work, I would not have been particularly moved. What I wanted was the ordinary restored, and in that moment I discovered how profoundly precious the ordinary is.

In the Scriptures we also discover that God grants ordinary requests. Seemingly buried in the long genealogical lists of 1 Chronicles is a brief story about a man named Jabez.

Jabez was more honorable than his brothers. His mother had named him Jabez, saying, “I gave birth to him in pain.” Jabez cried out to the God of Israel, “Oh, that you would bless me and enlarge my territory! Let your hand be with me, and keep me from evil, that I may not cause pain.” And God granted his request. (4:9–10)

What is not obvious is that the name Jabez means “he will cause pain” or “he makes sorrowful.” His request was for two things, both important, but hardly in the realm of the heroic. He asked that his work would prosper and that he might not live up to his name. No Goliaths are slain here, no kingdoms won or lost. And the Scriptures record for all to see that God was pleased to grant his request.

The Scriptures also underscore the significance of faithfulness in ordinary things, such as the hospitality that was shown by Gaius. The setting, according to 3 John, was apparently one of busyness and strife. Diotrephes, one of the members of the church, had been saying all sorts of outrageous things about the apostles and traveling brothers, refusing to welcome them. He even tried to stop the other believers from showing hospitality, and failing that, threw them out of the church. In the midst of all this a man named Gaius remained faithful. And then, a letter came from the great Apostle John addressed to Gaius himself. A thank-you letter. An expression of gratitude that Gaius has been faithful. He wasn’t part of one of the traveling missionary teams, nor was he apparently debating Diotrephes. He was involved, instead, in the very ordinary tasks that make up hospitality—changing beds, washing linens, cooking meals, going to the market, perhaps being the first to rise and the last to bed. And here, now part of inspired Writ, was a brief letter of thanks from the apostle, warmly expressing gratitude for Gaius’s faithfulness in the ordinary routine of his first-century life.

Ordinary Problems with the Extraordinary

If we fail to appreciate the wonder of our calling, we can grow disenchanted with faithfulness in the ordinary and the routine of life. If we imagine only the extraordinary is significant, we will fail to recognize the graciousness of God in offering to every believer the opportunity to live a life worthy of him. Heroes are few in number. Get too many lined up and soon the definition of heroism will have to be ratcheted up a notch or two. Significance doesn’t reside in the extraordinary for the Christian but in faithfulness. “Be faithful, even to the point of death,” the risen Lord told the church at Smyrna, “and I will give you the crown of life” (Revelation 2:10). If we forget that and pine for spectacular things, three deadly problems emerge.

The first problem arises when being enamored with the extraordinary makes ordinary Christian faithfulness appear insignificant. Not everyone can be Gideon; some of us have to be willing to stand off in the darkness holding a trumpet and a torch, yelling our heads off. Imagining that only Gideon’s role is worthy of consideration is to misunderstand the ways of God. The three hundred men who were there when the Midianites were defeated aren’t recorded by name in the Scriptures like Gideon was. Lost to history, they must be content to be remembered by God. Faithful Christians are content because they realize they live, moment by moment before the face of God. It’s easy to be faithful when there’s an adoring crowd cheering us on as we perform one heroic deed after another. The real test is whether we will be faithful in the unexciting details of everyday life when our only audience is God himself. Dismissing faithfulness because it is not spectacular enough to suit us is a danger we all face in an age when bigger and brighter are assumed to be better.

The second problem that arises when we desire the spectacular over faithfulness in the ordinary is that we can be blind to the evidence that God is at work in the mundane things of life. And a failure to recognize God’s Providence always results in ingratitude. God does extraordinary things—all things infinite are extraordinary to finite creatures. Sometimes, in his grace, he chooses to do some of them through his children. They may endure great things, or overcome great things, or accomplish great things, and the world may be forced to stop and wonder. But for all those things—and they are truly wonderful and numerous—the constant hand of God is at work graciously in our lives in a myriad of hidden ways. For all those healed throughout the centuries many more have been saved from infection by the Providence of God. For all those who have received meals miraculously supplied by ravens, countless more have received their daily bread. For all the servants of God who have been stoned and left for dead, many others were not harassed at all. If we see God only in the extraordinary we will miss the still quiet voice that speaks in the providential working of God’s grace in the ordinary details of life. And missing that, we will not be grateful and think it’s only luck, or perhaps even imagine that we have our cleverness to thank.

The third problem that arises when we mistake the extraordinary for the significant is that we end up with a sense of impotence. After all, the truly extraordinary is difficult to produce on command—in contrast, of course, to the merely extravagant or entertaining, both of which can, with modern techniques be readily manufactured. Unable to do anything spectacular, we either inflate what we do in our own minds or sullenly slog on, disappointed that our faithfulness will simply never amount to very much. We imagine that “what we do isn’t all that important” or whine that “we don’t seem to have much of an impact.” We accept our minority status in society with a deep sigh, pessimistic that much can change and are entertained by being shocked at the behavior of the surrounding barbarians. Os Guinness has spoken of Christians who boast of standing on the Rock of Ages but behave as if clinging to the last piece of driftwood. Since only the extraordinary could possibly be of true significance at such a needy moment, we seek out spectacular churches with extraordinary programs, hoping that though we are impotent, perhaps getting enough impotent people together in one place can make the difference.

Over against all this nonsense is the freedom of grace. The grace to live in the world God has made. Though now fallen, his calling to us to be faithful has not changed. He does not demand the spectacular and nowhere claims that only the few who transcend the ordinary are pleasing in his sight. This is part of what is meant by the biblical teaching that every believer is a priest. “The Reformation did not eliminate the priesthood,” Carl Henry writes, it

did away with a non-priestly laity; every follower of Jesus Christ was reminded anew of his calling to full-time priestly service. This emphasis did not so much secularize the ministry as it sanctified the laity. The Christian workman becomes a priest among his fellow-workers; he serves both God and neighbor as a daily sacrifice.13

Christ died so that something of the ordinary could be restored and someday that process will be consummated. In the meantime we can be faithful, sure that faithfulness in the ordinary and routine will be noticed by God, for that is what he has called us to.

What makes a difference in life is ordinary Christians being faithful in ordinary things. Miracles can be explained away. It’s possible for intelligent people to spend a lifetime studying God’s creation and still miss the clear evidence of his “eternal power and divine nature” (Romans 1:20). It was not spectacular crusades that turned the world upside down. It was ordinary believers being faithful in the routine of their lives, whether they were making tents or speaking at the Areopagus.

The record of history includes tantalizing glimpses of how such ordinary things can be significant. Os Guinness mentions one in The Dust of Death:

Kenneth Clark reminds us that in the sixth century Western Christianity survived only by clinging precariously to places like Skellig Michael, a tiny pinnacle of rock eighteen miles from the Irish coast, rising 700 feet from the stormy sea, and was thus “saved by its craftsmen.”14

The craftsmen involved may not have realized how significant their faithfulness was. They might not have given it a thought, but considered their task simply one more step in the fulfillment of their vocation.

Whatever fills our days and hours can be embraced with contentment and with deep hopefulness. God never promised that we would be able to see and identify the significance of our faithfulness. He promised only that it would not escape him.

A Stick Becomes the Staff of God

As Francis Schaeffer has noted, there is in the story of Moses’ staff a marvelous metaphor for being faithful in the ordinary and the routine of life.15 When God first spoke with Moses they talked, among other things, about his staff. It was the Lord who mentioned it initially. “Then the Lord said to him,” we read in Exodus 4:2, “‘What is that in your hand?’ ‘A staff,’ he replied.” It was a rod, a stick of wood.

We’re never told where Moses got his staff. Did he purchase it, perhaps in Midian, or did he bring it from Egypt? Was it perhaps a gift? Maybe he made it himself, carving it out of the heart of a tree. Or maybe he chose a branch because it was gnarled and twisted. If that was so, then it might have looked more like the snake it became when he threw it down at the Lord’s command. In any case, someone had to make that staff. Someone spent time and effort to dry the wood and carve it, sand and smooth it. Someone had to add creativity to a simple stick, until it became a tool of usefulness and comfort for a shepherd out in the wilderness alone with a flock of sheep. And because we believe in Creation we can see that even in sticks of wood there can be reflected something of the value of human creativity and faithfulness. But there is more to the story of Moses’ staff than this.

Moses’ staff illustrates vividly how a simple and ordinary thing can be used redemptively. It was only a stick, but when placed before the Lord of Hosts it could be used to the glory of God. By the time Moses left the presence of God in the burning bush that day, something astonishing had occurred: “So Moses took his wife and sons,” the Scriptures tell us, “put them on a donkey and started back to Egypt. And he took the staff of God in his hand” (Exodus 4:20, emphasis added). A stick of wood had become the staff of God.

Staffs keep reappearing in the narrative of the exodus from Egypt. God used Moses to give the Israelites reasons to believe in his promises and power (Exodus 4:31; 17:9). The staff became a testimony before the unbelieving Egyptians that God existed, and that he was not to be confused with the tribal gods and idols of paganism (Exodus 7:9, 15). Finally, a staff was placed in the ark of the covenant as a lasting memorial to the goodness and redemption of the Lord (Hebrews 9:4).

An ordinary object of human ingenuity and culture had been used of God to his glory in redemptive history. This is grace. But it’s a fallen world, and even sticks can be used for sin and evil. The ordinary stuff of everyday life can be used to God’s glory, or misused in the service of darkness. In sharp contrast to this stick, which became the staff of God, consider the sin of rhabdomancy. That is the name given to the occult practice of divination with rods. Apparently an invention of the Chaldeans, it was used to foretell the future and to make decisions.16 Rods were held upright and while an incantation was uttered, they were allowed to fall to the ground. How they landed and their relation to each other then revealed the oracle. These too were sticks of wood, but used in wickedness. The practice was found in Israel, and the prophet Hosea denounced its use. “They consult a wooden idol,” he wrote sarcastically, “and are answered by a stick of wood” (4:12).

Moses’ staff is an apt metaphor for the way God can use the ordinary things he has so graciously given us. We need not fear taking an inventory of our lives and discovering nothing but the ordinary there. The question of importance is not whether our resources and gifts appear to be limited or insignificant, but in whose service they are used.

Like Moses, we may find ourselves standing before the Lord with only a stick of wood in our hands. A mere stick, you say? Maybe so. Place it before the Lord of Hosts. Use it faithfully for his glory alone. Ask him to cause it to be a witness before all Creation that the God of the burning bush exists. And then stand back. He may allow you to watch what happens, or he may not. Whether it seems significant to us isn’t the important point. What is important is taking delight in the glorious freedom of the grace of God. For he has called us not to the extraordinary and the spectacular, but to faithfulness in the ordinary and the routine.