The Reforging of “Fundamentalism”

by S. M. Hutchens

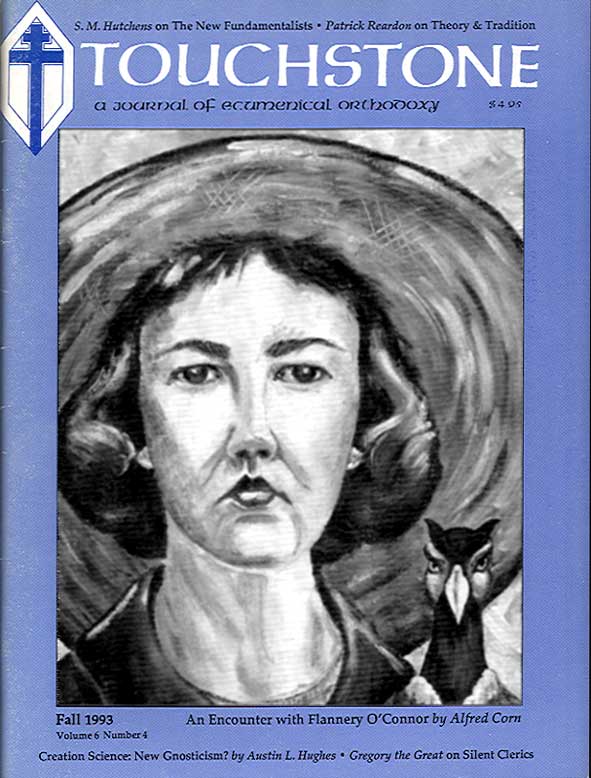

In the Easter 1991 issue of The Anglican Digest, a priest of the Episcopal Church holds forth on “The Dangers of Fundamentalism.” Likening the fundamentalist to the Nazi, he consigns them both to perdition along with other “hidden things of darkness.” Fundamentalism, he tells his readers, is passionate ignorance claming to own the whole truth. It is Ian Paisley screaming at Anglican peacemakers, Jimmy Swaggart confusing AIDS with God’s vengeance for sin, and the militant stupidity that censures professors of religion for a little harmless speculation. True Anglicanism, says the priest, is bound to tell people who sit in this kind of darkness, diminished and immobilized by fundamentalism, about the “true light, which lighteth every one that cometh into the world.”

The distribution of ideological prophylactics has become as important in mainline Protestantism these days as it ever was among the fundamentalists themselves. The Anglican Digest diatribe brings to memory Harry Emerson Fosdick’s widely read 1922 sermon “Will the Fundamentalists Win?” when that question caused as much concern in the upper reaches of the Protestant establishment as it does again today. When the principalities that run the denominations sense that churchgoers are becoming weary of the credal and ethical chaos that has been visited on them from the institutional high places—weary enough to start looking over the fences for something a bit more recognizably Christian—the patronizing smile, the slighting allusion, and the officially approved study material demonstrating that true Christianity has always been progressive, no longer suffice to keep the fundamentalist peril at bay. Once again the larger rhetorical war engines must be hauled out to close minds against closed-mindedness. An old-style religion must not simply be depreciated but demonized.

But here is a puzzlement: while one expects anti-fundamentalists salvos coming in from the left, the Anglican Digest represents the tidiest and most respectable kind of Episcopalian traditionalism. Why should publications of this type (the Digest is not alone in the Anglican world) seem to have it in for fundamentalists? Aren’t fundamentalists a world—that is, a social class or two—apart from the Episcopalians? And why the pressing concern to attack fundamentalism among those who profess to be moderates or conservatives? Why does one hear so many who sigh for the good old days take pains to let it be known that they abjure fundamentalism and all its works?

There is no surprise here for those who know the Episcopal Church. “Fundamentalism” threatens not only the coalition of liberals, feminists, and sundry political correctors who have captured its power structures, but also the demure traditionalists who quake chastely at the thought of violation by any kind of enthusiasm. To these the fundamentalist of chief concern is not the Baptist or Pentecostal safely on the other side of the ecclesiastical tracks, but the charismatic, evangelical, or similarly convinced member of his own fellowship who threatens to disturb the increasingly mausoleum-like peace of conventional Episcopalianism—to hug him before the offertory, to fill his quietly dying church with the unwelcome tumult of life, or, (quite unforgivably) to insist that what is happening to the Church these days is actually something to cause a commotion about. Despite their numerous antipathies, the modernist and the brittle traditionalist stand firmly united against the noisy barbarians massed on their common frontier. The fear of fundamentalism is upon them all, now more than ever.

Traditionalist Christians of the non-hugging variety should, however, be cautious about slinging the epithet about these days lest they find themselves pierced by their own dart. The definition of “fundamentalist” is being enlarged to include them. I am not referring here to its crass deployment to tar over anyone, Muslims or Methodist, who dares to offend the gods of inclusivism by insisting that truth excludes as well, but to its expansion within the churches themselves as a loosely defined term of reproach for anyone who takes issue with religious modernism on the grounds that it isn’t Christian. The cultured conservative who endorses the historic confession of his church but would prefer to put as much distance as possible between himself and the shabbier neighborhoods of Christendom needs to be told that the luxury of doing both is quickly evaporating. The days when a Michael Ramsey could rumble about the “menace of fundamentalism” are passing when an increasing number of his fellow bishops are using the word to describe anyone who believes the Creed and keeps to his own bed.

II.

One can hardly find a better example of the reforging of the term than in John Shelby Spong’s Rescuing the Bible from Fundamentalism: A Bishop Rethinks the Meaning of Scripture. The uninitiated (including non-Christians who thought they knew what Christians believed) may find this book shocking, but those who have been around a bit will recognize it simply as a short course in Bible as taught at the typical seminary, for it is, alas, what is believed about the Bible by the typical seminary professor these days. In the upper ranges of the mainline Protestant religious establishment (and increasingly, it appears, among Roman Catholic teachers of religion as well) there is nothing extraordinary about Bishop Spong’s opinions. He is still a member of his denomination’s House of Bishops in perfectly good standing, not having been censured, much less deposed, for the kind of opinions we will encounter below. What is stunning about Rescuing the Bible is its remarkable boldness in spilling the beans for popular consumption, sans the culinary art of the liberal pulpit, and outside the oldline schools of religion, with their unique facilities for making Christian postulants into agnostic social workers.

The bishop’s positive objective is to inform his readers that the Bible, while it cannot be read with the naïve credulity of the pre-critical—that is, the fundamentalist—mind, is still an immensely useful book. It is, in fact, a downright wonderful book, if approached intelligently. He is terribly fond of the Bible, knows it well, and so is all the more interested in rescuing its readers “from the clutches of a mindless literalism” that characterized the faith of his Baptist mother, whose religion was obviously less expansive than his own.

The word of God in scripture confronts me with the revelation that all human beings are created in God’s image. . . . all human beings. Men and women, homosexual persons and heterosexual persons, all races . . . —all persons reflect the holiness of God, for all are made in God’s image. How can I enslave, segregate, denigrate, oppress, violate, or victimize one who bears the image of the Holy One? That is the Word of God I meet in the Bible, [p.248]

An old-fashioned Christian of the “mindless” variety, when confronted with the warm, inclusive stew served up by Bishop Spong, can confidently be expected to have a serious attack of jerking knees. He will wish to discriminate between the ingredients of this motley pottage, to distinguish, for example, between innocent differences of race and gender and those stemming from corruption and error, between blind prejudice and frank recognition of diversity. In his bucolic simplicity the “literalist” may be expected to affirm that the bishop is right about everybody being made in God’s image, but wrong in thinking that this makes everyone acceptable to God, whatever he may believe or do. He will persist in theological nit-picking, asking the bishop if he actually believes, as he seems to imply, that the homosexual’s homosexuality is, like his humanity, derived from the divine image. The mindless literalist will, in short, insist on exhuming the whole encyclopedia of an obsolete orthodoxy and the myths upon which it is based, compulsively dividing light from darkness as befits his reactionary obsession. Mindlessness is a terrible handicap for those who insist on complicating things so much.

Rescuing the Bible is strategically organized. It begins with a ghastly portrait of what the bishop regards as fundamentalism in its purest form, then moves on to implicate its more sophisticated expressions. Spong grew up in a segregated South that used the story of Noah’s curse on Canaan to justify mistreatment of blacks, and full advantage is taken of the fact. Playing his harp in much the same manner as Anglican Digest priest, the bishop conjures visions of Jimmy Swaggart (for obvious reasons a great favorite in this kind of literature) and his unsuccessful bouts with the Devil, of Lester Maddox and his axe handles, of child beaters, of people who pray that planes carrying Spong will crash, of hate, insecurity, fear, bigotry, irrationality, violence, insularity, suspicion, vindictiveness, hypocrisy, self-righteousness, and stupidity—all these abominations propped up with the biblical literalism of the Virginia yokels among whom he was raised.

The point is not, however, about militant ignorance or the self-serving exegesis of decaying religious culture. If it were he would be bound to contend with conservatives who deplore these things much as he does. His real complaint is about any form of Christianity that is not in full communion with the Zeitgeist. Here, as in other places where it serves him, he refuses—or is unable—to distinguish between the deviant and the normal, in this case between a culture-bound religious conservatism and an orthodoxy with a strong enough sense of historical identity and respect for its constitution to resist modernist quidnuncery. The lurid hues in which Bishop Spong (without charity, but with a measure of justification) portrays the former are used to color all Christianity that does not conform to the radical modernist canon of truth. Everything retrograde from this point of view becomes fundamentalism, and every orthodox Christian a fundamentalist. While the sight of blood from Governor Maddox’s axe handles is still fresh, the bishop goes on to say:

The same mentality exists in more sophisticated mainline churches on more rational levels and with more complex emotional issues. These churches would be embarrassed if they had to defend the patterns of segregation among southern fundamentalists, but many of them are quite convinced that their prejudice toward women, for example, is a justified part of God’s plan in creation . . . .From the Pope, John Paul II, to the former presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, John Maury Allin, to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, to the outspoken Bishop of London, Graham Leonard [Lord Runcie and Bishop Leonard are now retired], the most remarkable words have been spoken to prove that the ‘unbroken tradition of two thousand years of an all-male priesthood,” is not a manifestation of the prejudice and sin of a patriarchal, sexist, society, but is rather a manifestation of the unchanging will of God supported by ‘the word of God’ in the Bible. [pp.5, 6]

There you have it, carried through on what the bishop obviously deems the clincher: How could any sensible person believe that denial of the priesthood to women rests on anything but prejudice and sin? And how could any fundamentally decent person deny them their manifest right to equal employment opportunity in the church? Clearly we are dealing here with a particularly odious combination of pride, stupidity and nastiness.

Bishop Spong would no doubt stipulate that John Paul II is not a fundamentalist in the original sense of the term, but still, he says, the Pope is marked by “the same mentality” as people who pray for his plane to crash. This deplorable spirit is manifest in papal reluctance to overthrow a 2,000-year-old tradition with roots firmly fixed in demonical practice and apostolic teaching—alas, supported once again, by a “literal” reading of the Bible. That women’s ordination has been accepted by eminently respectable denominations like the Episcopal Church does not seem to have impressed the Pope too much, and Bishop Spong clearly resents it. But mark well what he is saying here: the Pope’s convictions, and those who tend to look at doctrine and tradition as he does, are based upon a fundamentalist mentality, a mind characterized by a catalog of sins and spiritual diseases that would do credit to an archdemon.

The same mentality, Bishop Spong insists, shows itself in the historic homophobia of all major churches. In the past they have “simply quoted the Bible to justify their continued oppression and rejection of gay and lesbian persons” [p. 7]. But this sort of thing is unthinkable now that we live in a “world of superhighways, bright lights, and chain motels.” The bishop is convinced that the morality of a rigid orthodox Jew like St. Paul—probably a repressed homosexual himself—or ancient nomadic societies such as those that surrounded Sodom cannot possibly be transferred to our brave new world, which knows much more, which has been informed that people can inherit the proclivity toward homosexuality, and which understands that sexual preference can be placed on a continuum. “The authors of the Bible did not have the knowledge on the subject that is available to us today. The sexual attitudes in Scripture used to justify the prejudiced sexual stereotypes of the past are not holding in this generation. They are not in touch with emerging contemporary knowledge” [p. 9]—which is, of course, for Bishop Spong and all modernists, the first and final source of authority.

Here the gross literalist might counter that the Church’s belief in an inherited tendency toward sins of all kinds could account for much, and could protest that Christians have always known that hatred of the sin does not justify hatred of the sinner, confessing that they have indulged in hypocrisy about their own sins and failed to practice what they preach with regard to the sins of others. But it would not, perhaps, be wise to look to Bishop Spong for absolution. One cannot imagine that he would accept original and inherited sin, themselves hoary dogmas of a dead past, as explanations for anything, much less any confession that would attribute a measure of understanding, discrimination, liberality, or love to the dark, twisted mentality of fundamentalism—the mentality of Jerry Falwell, Jimmy Swaggart, Ezekiel, St. Paul and John Paul II.

Bishop Spong’s remedy for all this is precisely described by Friedrich Schleiermacher, the preeminent church father of religious liberalism, in his 1799 Speeches on Religion: Christianity as a historical-credal faith must be existentialized so that those who cannot accept its history or creed (that is, die Gebildeten—the intelligentsia) can find a home in the shell of religious sensibility that remains after the operation. Dr. Spong performs the procedure by “rescuing” the Bible and the Christian faith for those who can no longer believe the old myths and the prejudices that accompany them. For him the Bible is grist for new mills as much as it was for the old, and better the new mills—well, because they are the creatures of that infinitely flexible and elusive thing he calls “emerging contemporary knowledge.” His project is based upon the belief that while the Bible and the creeds are “valued documents in the faith journey of the people of God,” they are full of what sensible modern folk would call falsehoods. (And here Bishop Spong is not talking about the odd question of historical fact, either, but about most of what has been universally regarded as of the essence of the faith.) The way this is put is, “neither the Bible nor the creeds are to be taken literally or treated as if somehow objective truth has been captured in human words” [p. 233]. But not to worry, for Bishop Spong has managed to retrieve much genuinely heart-warming flotsam from the wreck of old-fashioned Christianity.

Given his skepticism on the commensurability of humanness and the truth, Spong’s view of the Incarnation is unsurprising. The Gospels’ birth narratives involve the evangelists’ intention to relate Jesus to Hebrew history, ergo they may be taken as total fabrication.

Am I suggesting that these stories of the virgin birth are not literally true? The answer is a simple and direct ‘Yes.’ Of course these narratives are not literally true. Stars do not wander, angels do not sing, virgins do not give birth, magi do not travel to a distant land to present gifts to a baby, and shepherds do not go in search of a newborn savior. I know of no reputable biblical scholar in the world today who takes these birth narratives literally [p. 215].

No mush-mouthed liberal, this! Bishop Spong can insert the heresy very nicely without the lubrication of the Sunset, Butterfly and Shaggy Dog stories so favored by the modernists of a gentler age. While he thinks the birth narratives charming stores that contain profound truth, this truth can be apprehended only when “the beast of literalism” is purged, that is, they can only become meaningful when taken as metaphors for certain aspects of the common experience of humanity, rather than as segments of the actual Event upon which all human experience is predicated. The antique Christianity Bishop Spong dislikes so intensely would hold that he has got it exactly backwards: the experience of the modern human being (of every age) derives its meaning from the positive, necessary—literal, if you will—truth of the story, and not vice versa.

At this point perhaps a parenthesis on the biblical scholarship to which Bishop Spong so frequently refers would be in order. The bishop is, in a sense, justified in his claim that there is no “reputable” biblical scholar in the world today who takes the birth narratives literally. But one must understand what this does and does not mean. It does not mean that there are no experts in biblical and theological studies who believe in the virginal conception of Christ, for there are many. It does mean that in the Western religious academy, as it is presently constituted, this is a minority opinion, a matter of personal belief irrelevant (at best) to the scientific study of the Bible, and an embarrassing relic of pre-Enlightenment religion that hampers the objectivity of those who persist in holding to the worldview from which it came. The prevailing naturalism of the seminaries and religious studies departments remains indifferent, or, if provoked, hostile to anything in heaven and earth that cannot be dreamt within the bounds of its philosophy, that is, outside the precincts of “emerging contemporary knowledge.” The nearly universal demand for “political correctness” in the modernist religious academies has given the coup de gráce to serious consideration of historic Christianity as an option for decent, intelligent people. Christianity as Christians have understood it throughout its history is patriarchal, Eurocentric, imperialistic, and oppressive—not simply (as the liberals told us) outdated, but an active expression of the deepest evil.

There is some delectable irony in the signs that the “modern” school of religion—actually only about two hundred years old now—is itself approaching the obsolescence to which it has so valiantly tried to consign the old superstitions. Dean Inge’s observation that whoever marries the Spirit of the Age will soon find himself widowed is beginning to show itself true here. In places where the most advanced winds of change are blowing the old naturalism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, of which Bishop Spong is a blunt and unmannerly vestige, is beginning to give way to the religion of the New Age. The supernatural is making a return, but this time not under Christian auspices. The new cosmologies are more spacious than those inherited from the Enlightenment, more “religious,” and therefore able to account for more than the narrow scientism of the old-fashioned modernist. Bishop Spong might be well advised to get with it if he wishes to keep up with the Spirit of the Age. Still, he is familiar with the world of critical scholarship as it presently stands, and quite right when he asserts that to cling to the belief that the birth, life and resurrection of Jesus happened basically as the Gospels say they did, is to give up a large measure of one’s reputability in the mainstream of biblical and theological studies and risk being sidelined with the fundamentalists.

Nowhere does the bishop’s burlesque of orthodox Christianity become more doggedly crude than in his account of the Ascension and post-Resurrection appearances.

When we turn to look with scholarly eyes at the resurrection narratives of the New Testament, the anxiety of the fundamentalists rises perceptibly. The birth narratives may be important to literalistic Christians, but they could abandon this outpost of their creed more easily and quickly than they could abandon the resurrection, by which they normally mean the physical, bodily resurrection of Jesus. Fundamentalist people like to quote Paul, that if Jesus be not risen ‘your faith is in vain’ (1 Cor. 15:17). Risen to them means physical rising and bodily resurrection. The birth accounts may be important to the Christian story, but the events of Easter are absolutely crucial. There can be no compromise here, no watering down of the essential details. Once again, it is helpful to fundamentalists not to read the Bible, for only in this way can their illusions be preserved. [p. 217].

Fundamentalists must, because of their insistence that the resurrection of Jesus was bodily and physical, retreat from the obvious implications of passages that indicate, for example, that he appeared in rooms with locked doors. St. Paul’s teaching that this was a “spiritual body” Bishop Spong finds impenetrable, except as evidence that whatever kind of appearance of Jesus the disciples experienced, it wasn’t physical. In his account of the Ascension we find the tiresome old chestnut that people who believe Jesus was received up into the clouds must be pre-Copernican troglodytes committed to belief in a three-tiered universe,

a flat earth covered by a domed ceiling beyond which heaven exists and God dwells. Jesus rises in order to enter keyhole in the sky to be enthroned at the right hand of God. . . . If Jesus ascended physically into the sky, and if he rose as rapidly as the speed of light (186,000 miles per second), he would not yet have reached the edges of our own galaxy [pp.30–31].

Quite clearly all of this belongs in the same category with singing angels, wandering stars, and virgin births. It is little wonder that John Spong was made a bishop. It is the least that could be done for a man who has such a comprehensive understanding de rerum natura and the corresponding limitations of God.

III.

Bishop Spong writes for a popular audience, but as he indicates, his point of reference is that of the more respectable segments of the religious academy. Here the affinity of fundamentalism as a significant moment in the history of American Protestantism and the historical consensus of orthodox Christianity has been reluctantly recognized for generations. In a frequently cited passage from The Religion of Yesterday and Tomorrow, Kirsopp Lake, an eminent New Testament scholar and no friend to fundamentalism, wrote,

It is a mistake often made by educated persons happen to have but little knowledge of historical theology, to suppose that fundamentalism is a new and strange form of thought. It is nothing of the kind; it is the partial and uneducated survival of a theology which was once universally held by all Christians. . . . No, the fundamentalist may be wrong; I think that he is. But it is we who have departed from the tradition, not he, and I am sorry for the fate of anyone who tries to argue with a fundamentalist on the basis of authority. The Bible and the corpus theologicum of the Church is on the fundamentalist side.

Here Professor Lake, writing in 1925, makes the same connection between the faith of the Fundamentalist Movement and historic Christianity that we have already seen in Bishop Spong’s equation of the “mentalities” of Rev. Swaggart, the pope, and St. Paul. Since the modernist correctly recognizes the faith of fundamentalism and of the historic Church as at base the same, all that has been needed to associate the dark side of the first with the truth shared by both is a dash of polemical intent.

The intent is abundantly present in the religious academy, which still finds fundamentalism a major irritant. Naturally, it is far less concerned about the fundamentalism of provincial Protestants than the immensely more muscular sort represented by the pope and the former bishop of London. Despite its frequent claim that the phenomenon is so discreditable as to be unworthy of consideration, there are clear signs that it is considered a very great deal. This is not only for the sake of the academy’s continuing obligation to relate deferentially, in public at any rate, to the superannuated religion in whose symbolic and institutional shell it lives and which still pays much of its way. Despite the condescension and hostility one finds here toward any form of classical Christianity, there remains a necessity to convince the world, and perhaps also itself, that its beliefs are in some reasonable and even historically plausible sense Christian. The only way this can be done is by redefining Christianity in terms of a pluralism that can include the mass of neologies it represents, but which therefore of necessity excludes those who regard these as errant. Those who believe the truth has boundaries described by divine revelation are the inclusivist’s only heretics, and an appropriate name must be found for them.

“Fundamentalism” was coined by a journalist in the early 1920s to identify the faith of a broad cross section of conservative Protestants (from Anglicans to Southern Baptists) who contributed to a widely distributed series of booklets entitled The Fundamentals. During the next few decades waves of mockery and contempt from literary, journalistic, and religious quarters, combined with other marginalizing forces, brought the term to the place where only the toughest-minded, most belligerent, and least urbane were willing to describe themselves as fundamentalists. Sine then the epithet has conveyed strong overtones of ignorance and contentiousness. The Evangelical Movement, deliberately and emphatically rejecting the fundamentalist label, was inaugurated in the forties with the very conscious intention of being identified as conservative but not fundamentalist. The fundamentalist stigma has remained floating about, however, too deliciously rank to be restricted to those who are willing to bear it, and temptingly available to detractors of old-style Christianity who would very much prefer not to honor it with names like “orthodoxy.”

David Tracy, a Roman Catholic who teaches, as did Kirsopp Lake, at the University of Chicago, does identify those who will not own up to modernity as “orthodox,” but for him orthodoxy is autistic, trapped incommunicado in its own confessional world by its rejection of pluralism, affirmation of which is the axis of his own theological method. Fundamentalism is the aspect of orthodoxy that denies truth by defining it not in terms of the radical freedom of agapaic love (which is to Tracy the essence of Christianity), but reducing it to super-naturalism.

To state the matter bluntly, for many of us fundamentalism and supernaturalism of whatever religious tradition are dead and cannot return. At their best, Western Christians have learned too well—as Nietzsche reminds us—the truth that Christianity taught. That truth is and remains that one’s fundamental Christian and human commitment is to the value of truth wherever it may lead and to that limit-transformation of all values signalized by the Christian demand for agapaic love. Fundamentalism of whatever tradition and by whatever criteria of truth one employs seems to me irretrievably false and illusory [Blessed Rage for Order, p. 135]

One example of fundamentalism Professor Tracy mentions is the willingness to take apocalyptic passages in the New Testament as referring to something “super-every-day.” Interpretation of Jesus’ sayings about the Kingdom of God, which sound like descriptions of events present, but also to be expected in the future, cannot be taken as they appear in the text by people with an educated sense of reality.

Literalize that language and that super-every-day world of super-naturalism called fundamentalism emerges. Observe that language transgresses the ordinary apocalyptic language it employs and a disclosure occurs. ‘Another’ world opens up: not an apocalyptic, super-every-day world; but a ‘limit’ dimension to this world, this experience, this language [p. 126, emphasis Tracy’s].

Does Professor Tracy mean the same thing here that Bishop Spong does when he speaks of miracle passages that cannot be taken literally? Unlike Bishop Spong, he does not indulge in overt denials of traditional Christian beliefs in his insistence on a complex unitary reality in which experience that is accounted religious is not apprehension of another dimension, but of a limit aspect to the world in which we already live. Crude attempts to attack this kind of thinking commonly end asserting a dualism in which God and creation are set apart in ways that do not accord with the Christology of Bible or Creed. Criticism of works of this kind requires not only caution, but the willingness to let many tempting indictments go by. In the end, however, the effect of theological treatises that assert that orthodoxy is merely the attempt to restate the beliefs of an isolated church tradition and needs revision in light of contemporary models of reality, seems opposed to a way of thinking in which there exists a “faith [along, one would presume, with its method] once delivered to the saints,” even if that faith was given in a form not as yet fully understood or elaborated. Christianity would seem to be monistic before it is pluralistic, dogma going before its dialogue with itself or with others. There is a fundamental difference between the similar viewpoints of St. Thomas, who recognized in doctrina sacra multa sunt occultanda, John Robinson, the Puritan for whom God has “more truth and light yet to break out of his holy Word,” and John Henry Newman, who understood Church teaching as arising from, and thus limited by, the potentialities of the apostolic seed, and that of the modernist, who really appears to have a completely new and different plant in view—a plant that lives on the elements of the old one, but only after the predecessor has been killed and reduced to compost.

IV.

I must admit that in all these things I am a confirmed “fundamentalist,” failing to see why belief in the “super-ever-day” makes me of necessity—as Bishop Song says and Professor Tracy implies—backwards and immoral. It would seem more reasonable to say that these men and I do not agree on what Christianity is, that we believe each other to be fundamentally wrong about some very important things. Whose perceptions and beliefs are right, and to what degree, is yet to be seen. (Of course, I speak here from the fundamentalist viewpoint, for this notion of “yet to be seen” is decidedly apocalyptic and “super-every-day.”) I am, moreover, probably because of my typically fundamentalist pusillanimity, put off by what Tracy and Spong would commend as “limit dimensions to this world” and “the depth of truth.” In so far as these encompass what a fundamentalist would be willing to call good, they would seem to rob it of its iconic quality, of its ability to point beyond this world, allowing us to enjoy actual communion with the reality that is as yet invisible to us. This is not “super-every-day” in a crude sense of the term, but a higher dimension that contains our own, and whose works in this one—whether they appear common or uncommon to us—are what the faithful call miracles, for believing in which people are stigmatized these days as fundamentalist. I can see no compelling reason to disbelieve in it—as long as one adheres to the rather fearsome and unromantic account of its reality found in the New Testament.

There also is a disturbing moral ambivalence lurking about Tracy’s and Spong’s doctrine. The fundamentalist in me has a hard time conceptualizing the consciousness and experience they recommend apart from what Christianity has historically regarded as sin. The Church has never canonized Nietzsche or John Humphrey Noyes, and has always harbored deep suspicion of people, be they bishops or Bogomils, who contemplate “limit experiences” without reference to the law of God, especially when they do it in the name of “agapaic love.” Keep in mind the conclusions urged upon the reader by Bishop Spong in his Living in Sin?, in which he makes it clear that in the realm of sexual ethics he is fully committed to advancing as good what Christians, Jews, Muslims, and just about everybody else, have always considered evil. So, one must ask whether taking mind-altering drugs, killing oneself, or any number of other abominable practices could stand approved by Bishop Spong and Dr. Tracy as authentic and valuable human experiences when they can be reckoned to evince agapaic love and the limit dimensions of this world. (The Episcopalian will hear the echoing voices of Bishop Pike and Professor Fletcher in this dark corridor.)

Those who live in what Chesterton called “fairyland”—a place where stars wander, angels sing, virgins give birth to saviors who die for their sins, are raised for their justification, and will take them some day (perhaps even up!) to a literal heaven—have a hard time feeling diminished and immobilized by their fundamentalism. It is the dry, chaotic little world of the modernists that looks small and dead to them. Ours is full of miracles, and we expect to see more of them yet. A mind captured by the kind of piety in which the Bible and the traditions of the Church can render up nothing more than political correctness and thin religious gushes that dry quickly on the hot sands of skeptical modernity does not seem worth saving the Bible for.

Let me express once again here the enduring wonder of the fundamentalist as to why the pluralist churchman bothers with Christianity at all. Why this seemingly arbitrary attachment to its symbolic life when there are other religions and philosophies—one might recommend Brahmanic Hinduism—that give coherent, adaptable, and satisfyingly religious (or trans-religious, if one prefers) explanations of the nature of things? There are other places where one would not have to deal with fundamentalists, or work so damnably hard at prying the faith from the myths, prejudices, and outright lies to which the simpler type of Christian will persist in seeing it so firmly attached.

Believers who consider themselves traditionalists, who sympathize with the tone of The Anglican Digest, The Living Church, and similar publications, wish everybody would quit fighting and be nice, and are quite sure that they dislike fundamentalism, would be well advised to open both eyes and survey the landscape of their churches—if they dare. Many are already living in conquered and occupied territory and will need to enlist the partisans the church and secular media are calling fundamentalists if they want the Christianity they have known but refuse to defend to remain available for their progeny. They will finally need to listen seriously to the critique of mainline religion they have evaded for so long because it comes from people they find convenient to avoid as ill-mannered and schismatic: That the benign traditionalism they thought would sustain them is too weak to carry, much less engender, Christian faith in a church environment created by progressively deeper capitulations to anti-Christianity, that the doctrinal and moral inclusivism now being pressed upon us on pain of being considered out of step includes what we know perfectly well is heresy and perversion, that preachments about the holiness of risk-taking from a compromised leadership sound like what the serpent said to Eve, and that what many of the most influential people in the churches are calling fundamentalism is what used to be called Christianity.

S. M. Hutchens is a senior editor and longtime writer for Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor