Saving the Theophanies

How to Restore & Transcend the Middle Ages

Although J. R. R. Tolkien played the major role in leading his friend C. S. Lewis to Christ, it was another member of the Inklings, Owen Barfield (1898–1997), who helped nudge Lewis along on his initial road to theism. Born in the same year as Lewis and educated, like Lewis, at Oxford, Barfield, though he spent 28 years as a working solicitor, managed to lead an active life as an author and philosopher of note. Indeed, after he retired from legal practice, he served as a visiting professor at various colleges and universities in America and Canada.

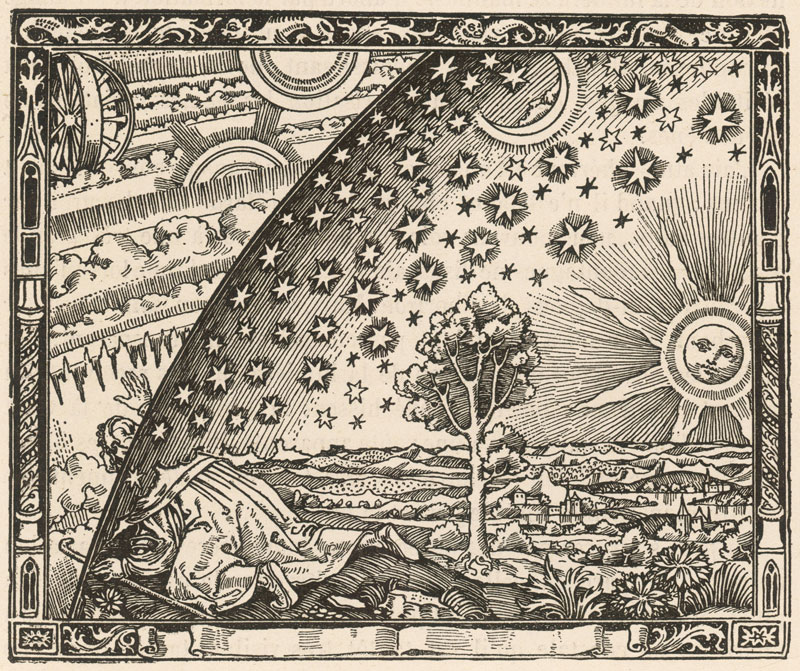

Though a committed Christian, Barfield was a student of the theories of the decidedly heterodox Rudolph Steiner (1861–1925), the father of anthroposophy. According to Steiner, after the fourth century a.d., when Christianity became institutionalized, Western man began the slow, grueling process of cutting himself off from the universe around him. Whereas people once experienced the world directly, participating in nature in an unmediated, naturally spiritual way, they increasingly came to view nature scientifically, as a dead object cut off from their own individual, subjective identity. Like the Romantics of the nineteenth century, anthroposophy sought—via the trinity of imagination, inspiration, and intuition—to heal this rupture of subject and object, mind and body, and to free man from viewing himself and others in purely abstract and reductively materialistic terms.

In what is arguably his finest work, Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry (1957), Barfield fused the key tenets of anthroposophy learned from Steiner with his own unique, and more Christian, understanding of the evolution of language and of human consciousness. Casting off the straitjackets of Darwinian scientism and logical positivism, he called on his modern readers to engage their sympathetic imagination in such a way as to recapture the original participation that existed between the ancients and their universe.

Modern science, Barfield argued, had killed the mystery of nature and the cosmos, not by telling us how they work (astronomy), but by telling us that they work apart from both ourselves and our Creator. The goal Barfield set for himself and for us was not to return to the naive, original participation of our forebears but to press forward to a higher kind of consciousness—what he called final participation—that would transcend the original as the New Jerusalem will the Garden of Eden or our resurrected bodies will the prelapsarian body of Adam.

In what follows, I will open up Barfield's accessible-but-challenging book by referencing two pairs of friends who spurred each other on to greater work and insight and who matured into Christian believers dedicated to the re-enchantment of the world: Lewis and Tolkien, and the Romantic poets Wordsworth and Coleridge. By so doing, I hope to demonstrate that Saving the Appearances is a book worth revisiting, one with a timely message that can help challenge modern Christians of an overly scientific/logical bent to perceive, and participate in, the fuller meaning of creation, consciousness, and the Incarnation.

Crisis & Resolution

Many of the finest lyrics penned by the British Romantics can be grouped together under the sub-genre of the crisis poem. In such perennial classics as Wordsworth's "Intimations Ode," Coleridge's "Dejection: An Ode," and Keats's "Ode to a Nightingale," the poet struggles with a loss of connection to the natural world, a loss that throws him into an intellectual-emotional-spiritual crisis that leaves him feeling cut off from the wellsprings of life around him.

In "Tintern Abbey," the model for all the crisis poems that would follow in its wake, the 28-year-old Wordsworth surveys his life vis-à-vis nature and discovers that he no longer feels the direct, unmediated unity with nature that he felt as a boy—when nature was, to him, "all in all." In those early days of unconscious communion and delight, the woods and waterfalls, the mountains and meadows were an "appetite; a feeling and a love / That had no need of a remoter charm, / By thought supplied, nor any interest / Unborrowed from the eye." But now, those "aching joys" and "dizzy raptures" have departed, leaving the adult feeling cold and disconnected.

Still, the poet does not mourn the loss, for something better has followed. Though he cannot regain what Barfield calls "original participation," he has found a new and richer "final participation," one that allows him to commune with nature on a deeper, conscious level that is unafraid to mingle joy with sadness, activity with contemplation. He can now step back from that nature that was once "all in all" to feel a "presence that disturbs [him] with the joy / Of elevated thoughts, a sense sublime / Of something far more deeply interfused," a something that dwells alike in nature and in "the mind of man."

Because he has achieved this final participation, the poet can regain and strengthen his love for all of nature. More than that, he can recapture "all the mighty world / Of eye, and ear,—both what they half create, / And what perceive." I will return later to explore more fully the shift from original to final participation. For now, I would like to zero in on the phrase "both what they half create, / And what perceive," for it provides the key to unlocking Saving the Appearances and its vital message for those stranded in a reductive, scientific age.

Louis Markos , Professor in English and Scholar in Residence at Houston Baptist University, holds the Robert H. Ray Chair in Humanities. His 19 books include Lewis Agonistes; Restoring Beauty: The Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the Writings of C. S. Lewis; On the Shoulders of Hobbits: The Road to Virtue with Tolkien and Lewis; and From A to Z to Narnia with C. S. Lewis.

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on C. S. Lewis from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor