Saving the Theophanies

How to Restore & Transcend the Middle Ages

Although J. R. R. Tolkien played the major role in leading his friend C. S. Lewis to Christ, it was another member of the Inklings, Owen Barfield (1898–1997), who helped nudge Lewis along on his initial road to theism. Born in the same year as Lewis and educated, like Lewis, at Oxford, Barfield, though he spent 28 years as a working solicitor, managed to lead an active life as an author and philosopher of note. Indeed, after he retired from legal practice, he served as a visiting professor at various colleges and universities in America and Canada.

Though a committed Christian, Barfield was a student of the theories of the decidedly heterodox Rudolph Steiner (1861–1925), the father of anthroposophy. According to Steiner, after the fourth century a.d., when Christianity became institutionalized, Western man began the slow, grueling process of cutting himself off from the universe around him. Whereas people once experienced the world directly, participating in nature in an unmediated, naturally spiritual way, they increasingly came to view nature scientifically, as a dead object cut off from their own individual, subjective identity. Like the Romantics of the nineteenth century, anthroposophy sought—via the trinity of imagination, inspiration, and intuition—to heal this rupture of subject and object, mind and body, and to free man from viewing himself and others in purely abstract and reductively materialistic terms.

In what is arguably his finest work, Saving the Appearances: A Study in Idolatry (1957), Barfield fused the key tenets of anthroposophy learned from Steiner with his own unique, and more Christian, understanding of the evolution of language and of human consciousness. Casting off the straitjackets of Darwinian scientism and logical positivism, he called on his modern readers to engage their sympathetic imagination in such a way as to recapture the original participation that existed between the ancients and their universe.

Modern science, Barfield argued, had killed the mystery of nature and the cosmos, not by telling us how they work (astronomy), but by telling us that they work apart from both ourselves and our Creator. The goal Barfield set for himself and for us was not to return to the naive, original participation of our forebears but to press forward to a higher kind of consciousness—what he called final participation—that would transcend the original as the New Jerusalem will the Garden of Eden or our resurrected bodies will the prelapsarian body of Adam.

In what follows, I will open up Barfield's accessible-but-challenging book by referencing two pairs of friends who spurred each other on to greater work and insight and who matured into Christian believers dedicated to the re-enchantment of the world: Lewis and Tolkien, and the Romantic poets Wordsworth and Coleridge. By so doing, I hope to demonstrate that Saving the Appearances is a book worth revisiting, one with a timely message that can help challenge modern Christians of an overly scientific/logical bent to perceive, and participate in, the fuller meaning of creation, consciousness, and the Incarnation.

Crisis & Resolution

Many of the finest lyrics penned by the British Romantics can be grouped together under the sub-genre of the crisis poem. In such perennial classics as Wordsworth's "Intimations Ode," Coleridge's "Dejection: An Ode," and Keats's "Ode to a Nightingale," the poet struggles with a loss of connection to the natural world, a loss that throws him into an intellectual-emotional-spiritual crisis that leaves him feeling cut off from the wellsprings of life around him.

In "Tintern Abbey," the model for all the crisis poems that would follow in its wake, the 28-year-old Wordsworth surveys his life vis-à-vis nature and discovers that he no longer feels the direct, unmediated unity with nature that he felt as a boy—when nature was, to him, "all in all." In those early days of unconscious communion and delight, the woods and waterfalls, the mountains and meadows were an "appetite; a feeling and a love / That had no need of a remoter charm, / By thought supplied, nor any interest / Unborrowed from the eye." But now, those "aching joys" and "dizzy raptures" have departed, leaving the adult feeling cold and disconnected.

Still, the poet does not mourn the loss, for something better has followed. Though he cannot regain what Barfield calls "original participation," he has found a new and richer "final participation," one that allows him to commune with nature on a deeper, conscious level that is unafraid to mingle joy with sadness, activity with contemplation. He can now step back from that nature that was once "all in all" to feel a "presence that disturbs [him] with the joy / Of elevated thoughts, a sense sublime / Of something far more deeply interfused," a something that dwells alike in nature and in "the mind of man."

Because he has achieved this final participation, the poet can regain and strengthen his love for all of nature. More than that, he can recapture "all the mighty world / Of eye, and ear,—both what they half create, / And what perceive." I will return later to explore more fully the shift from original to final participation. For now, I would like to zero in on the phrase "both what they half create, / And what perceive," for it provides the key to unlocking Saving the Appearances and its vital message for those stranded in a reductive, scientific age.

What They Half Create

There is no such thing, argues Barfield in chapter 3, as an "unseen rainbow" or an "unheard noise." The rainbow may exist potentially before it is seen by the eyes of a human being, but its full reality relies upon a conscious subject to perceive it. As strange and magical as it may sound, our seeing of a thing partakes in the making of that thing. Quantum mechanics has, for some time now, substantiated this claim—that a table is really made up of particles and waves and only "becomes" a table when a human subject perceives it as such—but that revelation has yet to permeate society. Even now, we would do better to hearken to Wordsworth's two-centuries-old discovery that our perceptions of nature half-create nature. Indeed, when Jesus healed the man born blind (John 9), he performed a double miracle: (1) he allowed the man, physically, to perceive images through his eyes; and (2) he enabled the man's brain to process those images into a coherent world of sea and sky, tables and trees, cats and canaries.

Barfield seconds Wordsworth's discovery, though he clarifies it by arguing that it is the collective perception of a rainbow that makes it real, since a single person could have a dream about a rainbow that was not real. He then extends his argument to take in the history of our planet, reminding us that "the prehistoric evolution of the earth, as it is described for example in the early chapters of H. G. Wells's [Darwinian] Outline of History, was not merely never seen. It never occurred" (ch. 5). We only think it occurred because, having turned nature into an object that exists wholly separate from us and our perceptions of it, we assume that the behavior of the unseen waves and particles has always been constant.

Darwinians, as Phillip Johnson pointed out thirty years ago in Darwin on Trial (1991), make an unfounded distinction between the theory of evolution, which is always in flux, and the fact of evolution, which they claim has been proven, despite the fact that no one was there to observe it. In a similar way, most moderns, secular or religious, take for granted that nature works separately from us and in a constant, uniformitarian (rather than catastrophic) way, even though, Barfield points out (ch. 9), that the Darwinian hypothesis rests, contradictorily, on "chance variation." But then, Barfield forces us to see, it is, for those of us living in the West, "a matter of 'common sense,' if not of definition, that phenomena are wholly independent of consciousness" (ch. 11).

A Mind of Metal & Wheels

When did Western man start making these assumptions about the nature of our world? It began a full two centuries before Wordsworth and the Romantic age, when Bacon and Galileo shifted the way we do science and view nature. For Bacon, the point of obtaining scientific knowledge was power, so that we can manipulate nature to do our will. In chapter 8, Barfield calls this "dashboard-knowledge," an operative, technological way of interacting with the world that cares only about the results obtained from using a natural world that has been reduced to a machine.

In The Lord of the Rings, this is the kind of instrumental magic practiced by the evil wizard Saruman, who, Treebeard explains, "has a mind of metal and wheels . . . [and] does not care for growing things, except as far as they serve him for the moment" (book 3, ch. 4). Such magic is sharply distinguished from the sympathetic (Barfield would say "participatory") magic of the elves, whose cloaks render their wearers invisible, not by the elves' exerting power over nature, but by their blending in (that is, participating) organically with the lore of wood and water and stone.

In chapter 3 of The Abolition of Man, Lewis identifies Bacon as pursuing the same type of instrumental magic as Faust:

For the wise men of old the cardinal problem had been how to conform the soul to reality, and the solution had been knowledge, self-discipline, and virtue. For magic and applied science alike the problem is how to subdue reality to the wishes of men: the solution is a technique; and both, in the practice of this technique, are ready to do things hitherto regarded as disgusting and impious—such as digging up and mutilating the dead. If we compare the chief trumpeter of the new era (Bacon) with Marlowe's Faustus, the similarity is striking.

Of course, none of this could have happened if men had not so cut themselves off from nature and their own bodies as to look upon both as mere cogs in a machine.

The Way Things Are

As for Galileo's role in objectifying nature, Barfield draws it out by contrasting Galileo with Copernicus. Why, one must ask, was Copernicus not condemned by the Church (and his fellow scientists!) when he suggested a heliocentric model of the universe, while Galileo was? The reason is that Copernicus only suggested that a different model of the universe—one that had been suggested by Aristarchus in the third century b.c.—might make better sense of what we perceive with our eyes. Copernicus merely sought, as so many ancient and medieval scientists before him had, to save the appearances: to bring into alignment the phenomena themselves and our perceptions of them.

Not so Galileo, who claimed "that the heliocentric hypothesis not only saved the appearances, but was physically true. It was this, this novel idea that the Copernican (and therefore any other) hypothesis might not be a hypothesis at all but the ultimate truth, that was almost enough in itself to constitute the 'scientific revolution.'" What Galileo claimed to discover when he looked through his telescope "was not simply a new theory of the celestial movement . . . but a new theory of the nature of theory; namely, that, if a hypothesis saves all the appearances, it is identical with truth" (ch. 7).

The upshot of this new theory was to turn nature into a machine that works by its own laws, separate from and independent of our perceptions of it. Unfortunately, Barfield maintains, when we objectify nature, we turn the phenomena of the world around us into idols, dead hollow things with no life in them. And when we do that, we transform ourselves into idolaters who, like the idols we worship, have eyes but do not see and ears but do not hear (see Psalm 115:3–8, which Barfield quotes several times). Thus, in objectifying nature, we eventually come to objectify ourselves.

The Fountain Within

Coleridge knew well the dangers of living in a dead world that could not be recalled to life by the perceptions of a perceiving subject. In "Dejection: An Ode," he is cast into a deep crisis when he realizes that, having lost his inner capacity for shaping nature into a thing of beauty, he can no longer be revived by nature alone, no matter the extent of her external beauty. "I may not hope from outward forms to win," he laments, "The passion and the life, whose fountains are within. / O Lady! we receive but what we give, / And in our life alone does Nature live: / Ours is her wedding-garment, ours her shroud!"

It is we, finally, who have the power to draw beauty and joy out of nature. When we lose that power, we become like "the poor loveless ever-anxious crowd" who only perceives in nature an "inanimate cold world." One of the goals of the Romantic movement—first in Germany and then in England—was to roll back the deadening and disenchanting effects of the Enlightenment by reunifying man (the subject) and nature (the object). Indeed, later in the poem, Coleridge expresses his faith that if, by means of a renewed inner sense of joy, nature could be wedded to the mind of man, that marriage would yield "in dower, / A new Earth and a new Heaven, / Undreamt of by the sensual and the proud."

This secularized (but not anti-Christian) version of the Great Marriage of Christ and the Church that will usher in the New Jerusalem (see Revelation 21–22) is perceived by Coleridge as a force that will not only renovate and illuminate us but make us more moral to boot! Barfield, too, insists that a movement away from dead literalness, from a hardness of heart that refuses to see, and participate in, God's creation, can undermine our idols and set our feet "on to the beginning of the long road, which in the end must lead [us] to self-knowledge, with all the unacceptable humiliations which that involves" (ch. 23). After all, Barfield reminds us, Jesus spoke in parables so that only those with eyes to see would see and ears to hear would hear (see Matt. 13:10–17).

Microcosm & Macrocosm

Coleridge begins "Dejection: An Ode" with an epigraph from an old medieval ballad that posits a direct, reciprocal relationship between the macrocosm of the heavens and the microcosm of man. It should come as no surprise that he does so, for the Medievals, as Barfield demonstrates, had not yet succumbed to the breakdown of subject and object that would follow in the wake of the scientific revolution.

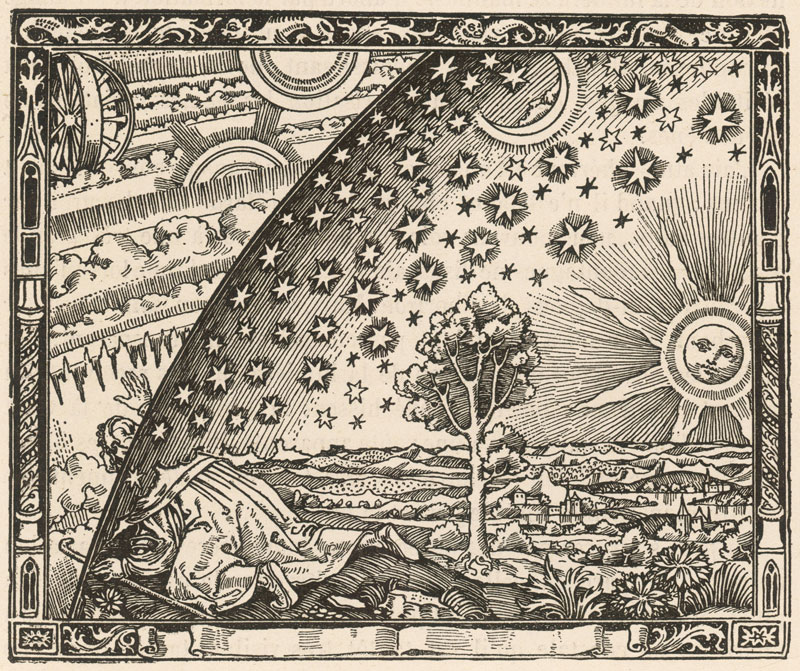

"Before the scientific revolution," explains Barfield, by means of a memorable double metaphor, "the world was more like a garment men wore about them than a stage on which they moved" (ch. 14). When we gaze upward, we see nothing but the cold vacuum of space; the Medievals saw something very different—a sympathetic cosmos throbbing with meaning and presence. Micro and macro were connected by an almost endless series of finely graded correspondences, with the movements of the planets shedding upon ourselves and our world a pattern of subtle influences that produced character traits in men and metals in the earth. The sun, for example, drew gold out of the earth and made men wise and generous, while Jupiter produced tin and made men jovial.

Lewis maps out the medieval cosmological model in all its glory and complexity in The Discarded Image and incarnates it (as Michael Ward has shown in Planet Narnia) in his seven Chronicles, but it is in Out of the Silent Planet, the first installment in his science-fiction trilogy, that he states the difference between our view and the medieval view in the clearest way. When Ransom, a modern man for whom nature is just so many dead idols, looks out the window of the spaceship that is taking him to Mars, he has a revelation that is pure Barfield:

He had read of 'Space': at the back of his thinking for years had lurked the dismal fancy of the black, cold vacuity, the utter deadness, which was supposed to separate the worlds. He had not known how much it affected him till now—now that the very name 'Space' seemed a blasphemous libel for this empyrean ocean of radiance in which they swam. . . . No: Space was the wrong name. Older thinkers had been wiser when they named it simply the heavens. (ch. 5)

From Garment to Stage

Moderns are too quick, argues Barfield, to think that the Medievals harbored a "false" view of the nature of space because they lacked knowledge or reasoned illogically or were incurably superstitious. In fact, the reason we view the world differently than they did is not that our ideas are more evolved than theirs but that our consciousness has changed radically since the scientific revolution.

Just as medieval theologians had no problem holding together the literal and allegorical meanings of Old Testament figures, events, and prophecies, so they did not make the kinds of (artificial) distinctions we make between the world and our perceptions of it. For modern man, the universe is a thing other than himself that works in accordance with objective, mechanical laws; for medieval man, it "was a kind of theophany, in which he participated at different levels, in being, in thinking, in speaking or naming, and in knowing" (ch. 14).

And the same distinction goes for most modern Christians as it does for the devotees of scientism. Thus, Barfield is forced to admit with sadness, "that valiant attempt, which began with the Reformation and ended in Fundamentalism, to understand and accept literally—and only literally—the words of the Bible," ended with the meanings of those words "being subtly drained away by idolatry" (ch. 23). That is to say, we have turned the Bible itself into an idol by giving it a "scientific" and "logical" existence that is cut off from our subjective participation in the Bible and the sacred narrative it relates.

I mentioned at the start of this essay that Tolkien was the one most responsible for leading Lewis to Christ. He accomplished that by suggesting to Lewis, who had dismissed the gospel as nothing more than the Hebrew version of the Corn-god myths of the Greek Adonis, Egyptian Osiris, Babylonian Tammuz, Persian Mithras, and Norse Balder, that the reason the gospel story sounded like a myth was that it was the myth that had become fact.

Literal & Allegorical

Tolkien's apologetic proved a powerful and effective one, but it is of a kind that Christians who have absorbed the Enlightenment split between subject and object, mind and nature, symbol and substance, myth and history generally refuse to allow into the Church. "If it were once admitted," writes Barfield, "that, for example, the Corn-god or the mystery religions had any significance for Christianity, or led up to it in any way, Christianity would itself promptly be assumed to be 'derived from' these religions and would dissolve away into anthropology and symbolism" (ch. 24).

Because the loss of original participation prevents Christians from viewing such biblical narratives as Creation and the Fall, the Flood and Babel, the near-sacrifice of Isaac, the Passover, the Bronze Serpent in the wilderness, the psalms of David, the dreams of Daniel, and the incarnation, death, and resurrection of Christ as being, simultaneously, literal-historical and allegorical-symbolical-mythical, we miss out on the fullness of the Scriptures and of God's mighty work in nature and in history. For a "non-participating consciousness," writes Barfield, a "narrative is either a historical record, or a symbolical representation. It cannot be both; and the pre-figurings of the New Testament in the Old, and the whole prophetic element in the Old Testament is now apt to be regarded as moonshine" (ch. 22).

Barfield does freely admit that the loss of original participation and our conscious awareness of the separate status of nature have led to important scientific discoveries and technologies that have improved medical treatments and helped feed the world. However, with those advances, have come losses, particularly for those who claim to worship a Savior who was the Word made flesh (John 1:14).

Christians believe that the Incarnation is the nexus point in the meaningful, directed—and thus non--Darwinian—flow of history (hence our use of b.c/a.d.) and that the incarnate Christ is the bridge between God and man who will reconcile us with our Creator and restore us to our central position in the created world.

For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God. For the creation was subjected to futility, not willingly, but because of him who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to corruption and obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God. (Rom. 8:19–21)

This is a glorious promise, but it is one that we can neither see nor embrace as long as we continue to cut ourselves off from what is not us.

From Original to Final Participation

What then shall we do? Shall we attempt a simple return to the Middle Ages and its view of the cosmos? Barfield's answer, like that of Lewis in The Discarded Image, is a clear "no." We should not, and cannot, cancel the evolution of our consciousness away from original participation. When we attempt to do so, we only open ourselves to bizarre avenues of thought and behavior.

Barfield finds traces of this attempt spread out over the previous two centuries. Many Romantics, especially the young, pre-Christian Wordsworth, often toyed with a return to pantheism, the belief that nature is pervaded by God and is finally one with God. Many of their artistic heirs turned toward an esoteric form of the arts that locates the true and final source of meaning in "a riot of private and personal symbolisms" (ch. 19).

In the twentieth century, many materialists turned, oddly, to the dream analysis of Freud and/or the collective unconscious of Jung, seeking meaning outside the bounds of that very material world that they believed made up all of reality. More recently, many in the West have gravitated toward Eastern monistic religions that offer as their ultimate goal the extinction of the self and its absorption into a cosmic One Soul. More generally, Westerners have sought secret wisdom from the occult and the New Age movement.

All of these are dead ends for both secular and religious seekers who feel the emptiness of idolatry but do not know how to heal that emptiness. What we must do is go forward rather than backward. The poet of "Tintern Abbey," as we saw above, matures into a new and different relationship with nature, one that knows and accepts its conscious separateness (nature is no longer "all in all") but then uses that consciousness to pursue a higher, wiser, more intimate connection that allows him to perceive and rejoice in "something far more deeply interfused." Just so, we of the twenty-first century must retain what the human race has achieved through the evolution of consciousness while yet having the courage to shatter the idols that prevent us from moving on to the next stage.

Coleridge, as we saw earlier, conceived of that next stage in the form of a marriage between mind and nature that would yield a new heaven and earth. For Coleridge and Wordsworth alike, it was the shaping power of the imagination that would effect that longed-for marriage. Steiner, too, looked to the imagination as the key to our growth into the next stage of consciousness. "Steiner," Barfield explains, "showed that imagination, and the final participation it leads to, involve, unlike hypothetical thinking, the whole man—thought, feeling, will, and character—and his own revelations were clearly drawn from those further stages of participation—Inspiration and Intuition—to which the systematic use of imagination may lead" (ch. 20).

From Judaism to Christianity

But what does this mean for the Christian, and how does it fit into the divine plan worked out in the Bible? To understand that, we must first understand what Barfield has to say about the unique contribution of the Jews. Whereas the loss of original participation happened in Europe through a long, slow process in the evolution of human consciousness, it happened in a historical moment of time among the Jews, when God, through Moses, forbade them from participating in nature in the way the pagan nations did.

While Barfield admits that God's linking of original participation with idol worship seems to contradict his own use of the term "idol" in Saving the Appearances, he quickly cleans up the seeming discrepancy by defining idolatry as "the valuing of images or representations in the wrong way and for the wrong reasons," or, more precisely, as "the effective tendency to abstract the sense-content from the whole representation and seek that for its own sake, transmuting the admired image into a desired object" (ch. 16). God's commandment against graven images was not meant to eliminate the possibility of final participation but to set in motion a plan that would eliminate a false (and sinful) kind of original participation as a prelude to a true union with God and his creation. Only through the death of the first could there be a rebirth into the second.

The crisis moment, the historical crux in that long evolution from death to a new and higher rebirth was the Incarnation, which Barfield describes in a unique and challenging way. "In one man the inwardness of the Divine Name ["I Am"] had been fully realized; the final participation, whereby man's Creator speaks from within man himself had been accomplished. The Word had been made flesh" (ch. 24).

Spoken by a hard-core anthroposophist, such a statement would carry with it the danger of collapsing the distinction between God and man and embracing something like a monistic One Soul. But Barfield was a Christian anthroposophist, and his celebration of the Incarnation is of a unique historical event when God became man and so bridged the divide between the Creator and his fallen creatures.

To make this clearer, Barfield holds up the Eucharist as a symbol instituted by God to embody and further the evolution from original to final participation, a sacrament that points backward to the Incarnation even as it points forward to the New Jerusalem and the Great Marriage of Christ and the Church. At present, we are caught in a "null point": one in which "the elimination of participation has deprived the outer 'kingdom'—the outer world of images, whether artificial or natural—of all spiritual substance, while the new kingdom within has not yet begun to be realized" (ch. 25). Still, we must press on, participating in the life of the Church as we hope someday to participate in the life of God himself, the Great "I Am" who sowed the Word (Logos) in the earthly soil of our world and our flesh.

The Kingdom of God Is Within You

When it comes down to it, Barfield is telling us what Jesus told a group of Pharisees: "the kingdom of God is within you" (Luke 17:21); however, he does not mean it in the way it has been used by theological liberals—as a way of internalizing the faith and cutting it off from its historical-supernatural moorings in the Incarnation, Atonement, and Resurrection. For Barfield, final participation is not some wishy-washy, Emersonian transcendentalist spiritualism but a transformational process by which the God who took on our mortal flesh is taking us up to participate in the indestructible, triune life of God.

Over the last half-century, an increasing number of young postmoderns have turned to New Age spiritualism as a way of finding an escape from the rampant materialism of our modern culture. Instead of casting them out, the Church, fueled by the vision expressed in Barfield's Saving the Appearances, should be inviting them in to a sacramental relationship with the Word made flesh. We might even read them the following passage, which, though it smacks of anthroposophy, contains a truth that is essentially and uniquely Christian: "If the Christ infuses my whole man, mind as well as heart, the cosmos of wisdom, with all its forgotten truths, will dwell in me whether I like it or not; for Christ is the cosmic wisdom on its way from original to final participation" (ch. 25).

If that seems too risky, too redolent of the heterodox (if not heretical) spiritual evolution of Henri Bergson and Teilhard de Chardin, we could read them this passage from book 4, chapter 7 of Lewis's Mere Christianity:

[A] real Person, Christ, here and now, in that very room where you are saying your prayers, is doing things to you. It is not a question of a good man who died two thousand years ago. It is a living Man, still as much a man as you, and still as much God as He was when He created the world, really coming and interfering with your very self; killing the old natural self in you and replacing it with the kind of self He has. At first, only for moments. Then for longer periods. Finally, if all goes well, turning you permanently into a different sort of thing; into a new little Christ, a being which, in its own small way, has the same kind of life as God; which shares in His power, joy, knowledge and eternity.

A Middle Way?

Lewis, Tolkien, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Barfield all discerned value in the medieval perception of and interrelationship with the cosmos, and their work was strengthened by their yearning to restore the lost unity of God, man, and the universe. Still, that does not mean that their views are exempt from a fair Christian critique.

A strong case can be made that Barfield and Lewis were too hard on Bacon, as Francis Schaeffer certainly was on Aquinas, Kierkegaard, and Barth. Bacon was, after all, a Christian, and his objective, democratizing scientific method helped free Western science from the domination of Aristotelian authority and so lead to inventions that truly improved the lives of Europeans and, through them, the world.

A strong case can also be made that Wordsworth and Coleridge, and their Romantic heirs, confused medieval thinking with pre-theoretical thinking and did not appreciate the good that can spring out of a proper objectifying of nature, one that allows for study and growth without a misuse of our divine commission to be stewards of nature. It would, I would argue, be better and fairer to say that Bacon, like Kant, opened a Pandora's Box that was used by secularists and materialists to peel away at the imago Dei and the reality of divine standards of goodness, truth, and beauty.

Is there then a middle position between a potentially obscurantist rejection of Bacon's advances and a nostalgia for pre-theoretical thinking on the one hand, and a too-quick embrace of the "benefits" of modern industrialism and the objectifying of man and nature on the other? I would suggest that the Catholic principle of subsidiarity, with its focus on doing things on the smallest and most local level possible—a principle that is embodied in the distributism of Chesterton and Belloc and that has parallels to the agrarianism of Wendell Berry and, less obviously, to the sphere-sovereignty principles of Abraham Kuyper, a key figure for conservative Reformed Christians—offers the potential for a kind of final participation that does not simply dismiss all forms of progress.

Lewis, Tolkien, Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Barfield can all, I submit, be fitted comfortably into that niche. One can imagine them, along with many of their fans, yearning for the Shire, whose Hobbit inhabitants, as Tolkien explains in the Prologue to The Lord of the Rings, "love peace and quiet and good tilled earth: a well-ordered and well-farmed countryside was their favourite haunt. They do not and did not understand or like machines more complicated than a forge-bellows, a water-mill, or a hand-loom, though they were skilful with tools."

Louis Markos , Professor in English and Scholar in Residence at Houston Baptist University, holds the Robert H. Ray Chair in Humanities. His 19 books include Lewis Agonistes; Restoring Beauty: The Good, the True, and the Beautiful in the Writings of C. S. Lewis; On the Shoulders of Hobbits: The Road to Virtue with Tolkien and Lewis; and From A to Z to Narnia with C. S. Lewis.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on C. S. Lewis from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor