Introduction

I am not a big fan of detective novels. I've read a few Sherlock Holmes stories, but I never caught the bug. And I have never read Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose.

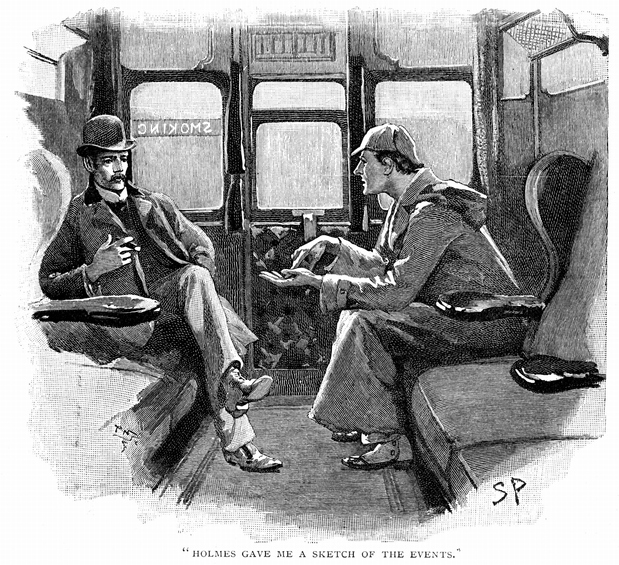

And so, if I was captivated by Louis Markos' October 2012 cover story, Detectives of Significance: Sherlock Holmes, Umberto Eco & The Search for Meaning, imagine what a proper fan of detective fiction will make of it!

Sherlock Holmes, Markos writes, "is not so much a detective as he is a monk without a monastery, a biblical exegete who can no longer see the New Testament prefigured in the Old, a theologian who has lost touch with God."

—Douglas Johnson, Executive Editor

(read more Editor's Picks)

Detectives of Significance by Louis Markos

Feature

Detectives of Significance

Sherlock Holmes, Umberto Eco & the Search for Meaning

by Louis Markos

Throughout the Middle Ages, most of the greatest Christian minds took for granted that the Bible was not to be read in terms of a linear, mathematical, one-to-one correspondence between words and their meanings, but polysemously. Formed from two Greek roots that mean "many" and "sign," polysemous, when used with reference to biblical interpretation, connotes a kind of active reading whereby one is able to see and grasp four levels of meaning working simultaneously in each verse and image of Scripture.

In a letter to one of his patrons, Dante offered a polysemous, four-fold reading of the verse, "when Israel out of Egypt came." Taken on the literal (or historical) level, the verse refers to the Exodus; taken allegorically (or typologically), it signifies how Christ freed us from sin; tropologically (or morally), it describes the conversion of the soul from its bondage to sin to its new freedom in Christ; anagogically (or spiritually), it prophesies the moment when the human soul will leave behind the body's long slavery to death and corruption and enter the Promised Land of heaven.

Such a vigorous, layered engagement with the words and images of Scripture is not to be attempted by the faint of heart. Those who like their truth served up cold, simple, and systematic will likely find medieval readings of the Bible to be bizarre, excessive, and even grotesque. But that is only because we, as post-Enlightenment modernists, have been kicked out of the medieval garden of allegory, symbol, and mysticism and now live east of Eden in a two-dimensional, foursquare world stripped of awe, wonder, and reverence.

In chapter V of his brief yet monumental Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages, Umberto Eco helps us understand what kind of world Dante grew up in:

The Medievals inhabited a world filled with references, reminders, and overtones of Divinity, manifestations of God in things. . . . Even at its most dreadful, nature appeared to the symbolical imagination to be a kind of alphabet through which God spoke to men and revealed the order in things.

This vast and shimmering universe of vertical and horizontal correspondences, which did not fully die until the seventeenth century (it is still very much alive in the poetry of John Donne and his fellow metaphysical poets), allowed the Medievals to discern connections and messages and prophecies not only in every verse of the Bible but also, ultimately, in every constellation, every line of poetry, and every blade of grass.

Although the Inklings (C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, and Owen Barfield) lived their lives and wrote their books as natives of this meaningful and meaning-giving cosmos, most of us, whether Christian or secular, do not. For us, the world is something to be studied, analyzed, and controlled. But for the ninth-century John Scotus Erigena, writes Eco, it was "a great theophany, manifesting God through its primordial and eternal causes, and manifesting these causes in its sensuous beauties."

A Form of Yearning For God

Modern lovers of technology and worshipers of progress tend to dismiss the Middle Ages as an era of stagnation, and yet, there existed in medieval thought a vibrancy lacking in our pragmatic, overly specialized universities. Eco captures this vibrancy in three passages scattered throughout chapter V.

Continue Reading

Louis Markos , Professor in English and Scholar in Residence at Houston Baptist University, holds the Robert H. Ray Chair in Humanities. His 19 books include Lewis

Agonistes; Restoring Beauty: The Good,

the True, and the Beautiful in the Writings of C. S. Lewis; On the Shoulders of Hobbits: The Road to Virtue with Tolkien and Lewis; and From A to Z to Narnia with C. S. Lewis.

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS

full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone

online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

24.1—January/February 2011

Secular Grendel

Ruminations on the Monstrous Envy of the Soul-Devouring State by Anthony Esolen

30.2—March/April 2017

Rescuing Cervantes

on Reading Don Quixote in Its Original Christian Context by Luis Cortest

more from the online archives

33.3—May/June 2020

Consolation in Death

Bach's Cantata BWV 106, Gottes Zeit ist die allerbesteZeit (God's time is the very best time) by Ken Myers

36.4—Jul/Aug 2023

Nothingness Rules

Our Political Void & the Disintegration of Truth by Michael Hanby

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor

Support Touchstone

00