Detectives of Significance by Louis Markos

Feature

Detectives of Significance

Sherlock Holmes, Umberto Eco & the Search for Meaning

by Louis Markos

Throughout the Middle Ages, most of the greatest Christian minds took for granted that the Bible was not to be read in terms of a linear, mathematical, one-to-one correspondence between words and their meanings, but polysemously. Formed from two Greek roots that mean "many" and "sign," polysemous, when used with reference to biblical interpretation, connotes a kind of active reading whereby one is able to see and grasp four levels of meaning working simultaneously in each verse and image of Scripture.

In a letter to one of his patrons, Dante offered a polysemous, four-fold reading of the verse, "when Israel out of Egypt came." Taken on the literal (or historical) level, the verse refers to the Exodus; taken allegorically (or typologically), it signifies how Christ freed us from sin; tropologically (or morally), it describes the conversion of the soul from its bondage to sin to its new freedom in Christ; anagogically (or spiritually), it prophesies the moment when the human soul will leave behind the body's long slavery to death and corruption and enter the Promised Land of heaven.

Such a vigorous, layered engagement with the words and images of Scripture is not to be attempted by the faint of heart. Those who like their truth served up cold, simple, and systematic will likely find medieval readings of the Bible to be bizarre, excessive, and even grotesque. But that is only because we, as post-Enlightenment modernists, have been kicked out of the medieval garden of allegory, symbol, and mysticism and now live east of Eden in a two-dimensional, foursquare world stripped of awe, wonder, and reverence.

In chapter V of his brief yet monumental Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages, Umberto Eco helps us understand what kind of world Dante grew up in:

The Medievals inhabited a world filled with references, reminders, and overtones of Divinity, manifestations of God in things. . . . Even at its most dreadful, nature appeared to the symbolical imagination to be a kind of alphabet through which God spoke to men and revealed the order in things.

This vast and shimmering universe of vertical and horizontal correspondences, which did not fully die until the seventeenth century (it is still very much alive in the poetry of John Donne and his fellow metaphysical poets), allowed the Medievals to discern connections and messages and prophecies not only in every verse of the Bible but also, ultimately, in every constellation, every line of poetry, and every blade of grass.

Although the Inklings (C. S. Lewis, J. R. R. Tolkien, Charles Williams, and Owen Barfield) lived their lives and wrote their books as natives of this meaningful and meaning-giving cosmos, most of us, whether Christian or secular, do not. For us, the world is something to be studied, analyzed, and controlled. But for the ninth-century John Scotus Erigena, writes Eco, it was "a great theophany, manifesting God through its primordial and eternal causes, and manifesting these causes in its sensuous beauties."

A Form of Yearning For God

Modern lovers of technology and worshipers of progress tend to dismiss the Middle Ages as an era of stagnation, and yet, there existed in medieval thought a vibrancy lacking in our pragmatic, overly specialized universities. Eco captures this vibrancy in three passages scattered throughout chapter V.

First, in their ongoing search for the eternal essences that lay behind biblical, natural, and poetic symbols, the Medievals, explains Eco, "took great pleasure in deciphering puzzles, in spotting the daring analogy, in feeling that they were involved in adventure and discovery." The key thinkers of the Middle Ages valued stability and tradition in their daily lives, but that did not prevent them from setting forth on spiritual, philosophical, and aesthetic quests. Like the Romantics after them, the Medievals sought to pierce the veil, to discover what lay behind the words, ideas, and images that made up their daily lives.

Indeed, Eco discerns in the "metaphysical symbolism" of the twelfth-century Hugh of St. Victor (one of the masters of the four levels of meaning) "an almost Romantic sense of the inadequacy of earthly beauty, which provokes in him who contemplates it that sense of dissatisfaction which is a form of yearning for God." This sense of inadequacy should not be confused with the Gnostic rejection of physical matter as inherently fallen; rather, it arises from a deeply held sense that there is more to goodness, truth, and beauty than we can perceive with our senses.

And that takes us back to the medieval "obsession" with reading poetry in general, and the Bible in particular, in terms of two or three or four levels of meaning. Such a system of reading seems forced and unnatural to us, a mere exercise in obfuscation, but it was not so to them. "Interpreting poetry allegorically," argues Eco, "did not mean imposing upon it some kind of arid and artificial system. It meant seeking in it what was felt to be the highest possible pleasure, the pleasure of a revelation per speculum in aenigmate." Eco borrows the Latin phrase from 1 Corinthians 13:12: "For now we see through a glass darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known." Perhaps no verse in the Bible better explains the impetus behind the medieval quest for higher truths and essences. What waits for us on the other side is not just answers, but also Meaning, Purpose, and Presence.

Holmes & William

Though Eco published Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages in 1959, it was not translated into English until 1986 (by Hugh Bredin). The reason for the delay is that Eco did not become a household name outside Italy until he published his widely read and critically acclaimed novel, The Name of the Rose (1980; English translation by William Weaver, 1983; film adaptation, 1986). The novel, set in an Italian abbey in 1327, concerns a series of strange murders, all of which are linked to a secret book hidden in the abbey's renowned and carefully guarded library.

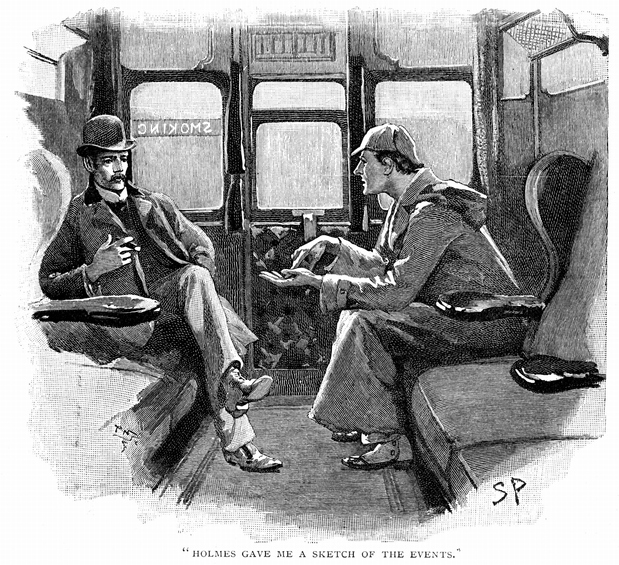

The mystery is solved by a former inquisitor and Franciscan monk whose powers of detection are closely patterned after those of Sherlock Holmes (Eco playfully names his protagonist William of Baskerville). William is even assisted by a brave if sometimes foolhardy sidekick/chronicler named Adso, who, like Dr. Watson, is less astute than William, but loyal, eager to learn, and more in touch with his emotions than the great detective.

Most of Eco's reasons for linking William so closely to Holmes are obvious: It renders his often erudite novel more accessible to a general audience; it allows William to display some wonderful feats of deduction; it helps draw out William's character as brilliant and noble yet somehow cold and aloof; it helps modern audiences accept William's monkish suspicion of women by refracting it through Holmes's mistrust of the female sex and his borderline misogyny. But there is also, I would suggest, one less obvious reason for the connection. That reason has to do with the curious fact that, though Sherlock Holmes embodies Victorian rationalism to perfection, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's "unofficial consulting detective" betrays, behind his serene mask of logic, a kind of divine discontent that is almost medieval.

I would like to trace this most singular paradox in Conan Doyle's first collection of stories (Adventures of Sherlock Holmes) and best Holmes novel (The Sign of Four) and then move both forward and backward to Eco's twentieth-century novel and its fourteenth-century setting in search of that wider longing for Meaning and Purpose that defines us as a species.

"Whole Man" Involvement

In the first chapter of The Sign of Four, Holmes berates Watson for the sentimental liberties he took in writing A Study in Scarlet (the first Holmes novel):

Honestly, I cannot congratulate you upon it. Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science and should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted to tinge it with romanticism, which produces much the same effect as if you worked a love-story or an elopement into the fifth proposition of Euclid.

In the last chapter, when Watson announces that the heroine, the lovely Miss Morstan, has accepted his proposal of marriage, Holmes finds himself unable to congratulate his friend on that, either, commenting instead that "love is an emotional thing, and whatever is emotional is opposed to that true cold reason which I place above all things. I should never marry, lest I bias my judgment."

This is the Holmes most familiar to readers: impervious to feelings, interested only in objective details and quantifiable facts, committed to a life of pure reason, and unswayed by the vagaries of faith, hope, and love. Positivism, with its empirical insistence on trusting only the senses, its belief that metaphysical superstition has been superseded by scientific rigor, and its utilitarian focus on progress, was all the rage in Victorian England.

Holmes appears, at least on the surface, to be a vanguard of the brave new utopian world that was to be built by properly enlightened sociologists and engineers.

But that is not the whole story. In "The Boscombe Valley Mystery," Watson reveals the dual nature that lurks beneath the façade of the calculating machine:

Sherlock Holmes was transformed when he was hot upon such a scent as this. Men who had only known the quiet thinker and logician of Baker Street would have failed to recognize him. His face flushed and darkened. His brows were drawn into two hard black lines, while his eyes shone out from beneath them with a steely glitter. His face was bent downward, his shoulders bowed, his lips compressed, and the veins stood out like whipcord in his long, sinewy neck. His nostrils seemed to dilate with a purely animal lust for the chase, and his mind was so absolutely concentrated upon the matter before him that a question or remark fell unheeded upon his ears, or, at the most, only provoked a quick, impatient snarl in reply.

Holmes is often depicted as a ratiocinative detective who solves his criminal puzzles in the pure, abstract realm of thought, but his absorption in a case is often as much physical as it is mental. The full man is given over to the search—body, soul, and mind. "When he had an unsolved problem upon his mind," Watson tells us in "The Man with the Twisted Lip," he "would go for days, and even for a week, without rest, turning it over, rearranging his facts, looking at it from every point of view until he had either fathomed it or convinced himself that his data were insufficient."

A Yearning for More

Is there a key to Holmes's complex character? I think there is, and I think it is directly related to one of the most controversial aspects of Conan Doyle's adventures: the otherwise rational detective's addiction to cocaine. This side of Holmes is first revealed in the opening chapter of The Sign of Four. When Watson takes him to task for his unhealthy habit, Holmes at first tells him that he finds the drug "transcendently stimulating and clarifying to the mind." A moment later, however, he reveals to the good doctor the true reason for his addiction:

"My mind," he said, "rebels at stagnation. Give me problems, give me work, give me the most abstruse cryptogram, or the most intricate analysis, and I am in my own proper atmosphere. I can dispense then with artificial stimulants. But I abhor the dull routine of existence. I crave for mental exaltation. That is why I have chosen my own particular profession, or rather created it, for I am the only one in the world."

The physical world, it seems, with its mass of details and its natural laws, is not enough. Holmes yearns for more; he needs more. He must have a riddle to solve, an adventure to pursue, a quest to test his powers of deduction. When none presents itself to him, he turns to cocaine to stimulate his brain and make it work outside the boundaries of the quotidian.

Later in the chapter, Holmes explains further his inability to live in a world that does not challenge or stimulate his higher faculties:

"I cannot live without brainwork. What else is there to live for? Stand at the window here. Was ever such a dreary, dismal, unprofitable world? See how the yellow fog swirls down the street and drifts across the dun-coloured houses. What could be more hopelessly prosaic and material? What is the use of having powers, Doctor, when one has no field upon which to exert them? Crime is commonplace, existence is commonplace, and no qualities save those which are commonplace have any function upon earth."

A Monk Without a Monastery

For Holmes, a mundane, one-dimensional reality is as prosaic, as numbing as a biblical verse with only a simple literal meaning would be to a medieval allegorist. For Holmes, as for Dante, John Scotus, and Hugh of St. Victor, a world that has only one meaning is the same as a world that has no meaning. How pragmatic and utilitarian the Victorian Holmes seems at first: that is, until we pierce beneath the surface to find a man who is divinely dissatisfied with—who is, in fact, repelled by—all that is pragmatic and utilitarian.

"It saved me from ennui," says Holmes after cracking the case of the Red-headed League; but the salvation is short-lived. A second later, he exclaims: "Alas! I already feel it [ennui] closing in upon me. My life is spent in one long effort to escape from the commonplaces of existence." Dante might have said the same as he painstakingly constructed his tri-partite universe. We live in the world, but the world is not enough. We are rational creatures who use our reason to survive, yet neither reason nor survival is sufficient.

"The days of the great cases are past," complains Holmes in the opening of "The Adventure of the Copper Beeches," "Man, or at least criminal man, has lost all enterprise and originality." It may seem to us both strange and callous that Holmes would bemoan the loss of originality in the criminal mind. Surely a true detective should pray for an end to crime, even as a true soldier should pray for the end of war. But Holmes needs his Moriarty, for, without him, he cannot achieve transcendence, he cannot press beyond the limits of the commonplace to discern meaningful connections between the mundane details of the world.

For Holmes is not so much a detective as he is a monk without a monastery, a biblical exegete who can no longer see the New Testament prefigured in the Old, a theologian who has lost touch with God.

The Complete Holmes

And that takes us back to Umberto Eco's novel and its Holmesian hero, William of Baskerville. In the opening scene of "The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle," Holmes deduces a man's character and life experiences by studying his hat. In the second chapter of The Name of the Rose, William deduces a complex sequence of events by studying a set of hoof prints in the snow. When Adso expresses wonder at his master's abilities, William urges him "to recognize the evidence through which the world speaks to us like a great book."

He then quotes three lines of a Latin poem which, translated into English, read: "All the world's creatures, / as a book and a picture, / are to us as a mirror." The writer of the lines, William tells Adso,

was thinking of the endless array of symbols with which God, through His creatures, speaks to us of the eternal life. But the universe is even more talkative . . . it speaks not only of the ultimate things (which it does always in an obscure fashion) but also of closer things, and then it speaks quite clearly.

After they finish their conversation, Adso explains to his reader that William "not only knew how to read the great book of nature, but also knew the way monks read the books of Scripture."

William, in other words, is the complete Sherlock Holmes. He not only can read the Book of Nature, but the Book of God as well. A disciple of the Franciscan Roger Bacon, whose attempt to put the sciences on par with philosophy and theology earned him a charge of heresy, William is a student of both physical and metaphysical realities. Like Holmes, he finds that the clearest messages come to him via the concrete, empirical details of this world; unlike Holmes, he is willing also to contemplate the signs and symbols that point heavenward. He is God-haunted in a way that Holmes is not.

Or, better, in a way that Holmes does not know—or will not know—that he is. If I may turn Freud against himself, I would suggest that God does speak to Holmes through his passionate love of music, but that the detective, unable to quantify such beauty in empirical terms, sublimates his passion (downward rather than upward) into an obsession with ordering the obscure and scattered clues that betray the greater, almost supernatural mind of the master criminal.

The Metaphysical Shudder

In a "Postscript" to his novel that he published in Italian in 1983, Eco explains to his readers why he chose to present his story in terms of a popular, rather than academic, genre: "since I wanted you to feel as pleasurable the one thing that frightens us—namely, the metaphysical shudder—I had only to choose (from among the model plots) the most metaphysical and philosophical: the detective novel."

Apparently, the Victorian Holmes is not the only person who shudders in the face of the metaphysical, who feels a numinous thrill when brought before that which is beautiful and terrible at once, that which simultaneously exalts and crushes the human spirit. The search for a guilty person (or persons) catapults us into a moral world of right and wrong, even as it beckons us to line up the clues, to discern a meaningful pattern that will bring order and clarity to a situation that is dark, troubling, and chaotic.

Eco not only hides his secret book within a multi-language manuscript that is itself hidden within a labyrinthine library, but he also sets his detective story within a wider search for certainty in an age in which it has become difficult to discern friend from foe, spiritual from temporal, reformer from heretic, guardian from destroyer, Christ-like leader from the spirit of antichrist. Eco even creates a monstrous character named Salvatore who speaks a Babel-like language that jumbles together words from Latin, Greek, and half a dozen vulgar tongues. Adso himself has a sexual encounter with a village girl that causes him to confuse the natures of spiritual and erotic love. Symbols abound in Eco's densely woven novel, but those symbols shift their meanings in a constant dance of visual and linguistic signs.

William and Adso are brought to the abbey to help mediate a dispute between the pope and the Holy Roman Emperor. Their mission proves a failure, but Adso is surprised to discover that his master is less worried about his failure, and the terrible consequences it will have throughout Europe, than he is about finding the book and the murderer. In strongly Holmesian words, William explains to Adso that he finds

the most joyful delight in unraveling a nice, complicated knot. And it must also be because, at a time when as philosopher I doubt the world has an order, I am consoled to discover, if not an order, at least a series of connections in small areas of the world's affairs.

This is a strange statement to come from a mind as brilliant and disciplined as that of William of Baskerville. If he doubts that there is order in the world, why is he so intent on discerning order? Perhaps he is saying that if he can find order on the microcosmic level, then that will suggest that order exists as well on the macrocosmic. In any case, his passion for the search is increased, not diminished, by his doubts.

The Ultimate Signified

In the end, he solves the puzzle and catches the Moriarty-like mastermind behind the trail of deaths (a man named Jorge), but his victory is hollow, for he arrives at it by following all the wrong signs and making all the wrong assumptions. In his last dialogue with Adso, as the seventh day of the search concludes, William pours out his frustrations:

I have never doubted the truth of signs, Adso; they are the only things man has with which to orient himself in the world. What I did not understand was the relation among signs. I arrived at Jorge through an apocalyptic pattern that seemed to underlie all the crimes, and yet it was accidental. I arrived at Jorge seeking one criminal for all the crimes and we discovered that each crime was committed by a different person, or by no one. I arrived at Jorge pursuing the plan of a perverse and rational mind, and there was no plan, or, rather, Jorge himself was overcome by his own initial design and there began a sequence of causes, and concauses, and of causes contradicting one another, which proceeded on their own, creating relations that did not stem from any plan. Where is all my wisdom, then? I behaved stubbornly, pursuing a semblance of order, when I should have known well that there is no order in the universe.

Though William is no more an autobiographical mouthpiece for Eco than Holmes is for Doyle, Eco's medieval hero expresses here something of a postmodern angst over the unreliability of signs. Derrida initiated deconstruction by arguing that every time we seek to trace a word (or signifier) back to its origin (or signified), we find that the thing we thought was a signified is just another signifier. And if we try again to get back to the origin—to the Center, the Cause, the Meaning—we find that each new signifier leads only to more signifiers in an endless chain.

But, of course, that is not what happens in the vast majority of detective novels, including The Name of the Rose and the many cases of Sherlock Holmes. William followed the wrong chain of signifiers, and even got sidetracked onto the wrong signification system, but he did find the book and the mastermind. There is an Origin, a Cause, a Meaning, and we as human beings are impelled to seek it out, even if we cannot understand all the ramifications of our discovery. And why are we impelled to do so, and why, if we seek, are we sure to find? That reason is stated clearly in the opening paragraph of Eco's novel:

In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God, and the word was God. This was beginning with God and the duty of every faithful monk would be to repeat every day with chanting humility the one never-changing event whose incontrovertible truth can be asserted. But we see now through a glass darkly, and the truth before it is revealed to all, face to face, we see in fragments (alas, how illegible) in the error of the world, so we must spell out its faithful signals even when they seem obscure to us and as if amalgamated with a will wholly bent on evil.

Christ, the Word of God, is the ultimate Signified, and the historical, spatio-temporal event when that Word took on flesh (the Incarnation) marks the central moment in human history, a moment that gives meaning to all that comes before and after. Yes, Adso admits, we live in a fragmented, error-filled world, and we see, when we see at all, through a glass darkly, but the Center, the Logos, exists, and so it is right that we spend our lives in search of signs—and the meaning (and Meaning) that lies behind them.

Adrian's Indictment

Postscript: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was also a seeker after signs. Not only did he fashion a fantasy world on the margins of our own (The Lost World) and write a novel (The White Company) set in the same century as The Name of the Rose, but he ended his life as an avid disciple of spiritualism, eager to prove through scientific means the persistence of life after death. His late passion for spiritualism seems to have been sparked by the horrors of World War I and the loss of his son and brother to pneumonia in 1918 and 1919.

Several years ago I had the opportunity to view a video recording of an interview with Doyle's son Adrian. The interviewer asked him why it was that the man who had invented the most logical detective of all time had devoted so much of his time and resources to spiritual research. Adrian's reply has etched itself into my mind, as it should into the minds of all who care about the Christian Church.

During World War I, Adrian Conan Doyle explained, a whole generation of Europeans was wiped out by war and disease. In pain and bewilderment, the survivors looked to the Church for answers: Were all those victims of the Great War gone, or did their lives, their personalities, persist beyond the grave? According to the son of the creator of Sherlock Holmes, the "churches were totally incapable of giving a reply"; they "had no answer to anything"; they "could give no answer." It was because of that failure that Doyle and other scientists of his age sought for empirical evidence to verify the immortality of the soul.

I vividly remember Adrian's words, not only because of what he said but also because of how he said it. He spoke his condemnation of the impotent liberal church of twentieth-century Europe—the same church that would frustrate Dietrich Bonhoeffer during World War II—with a sad but smoldering outrage reminiscent of the righteous anger that Jesus unleashed upon the Pharisees. Blind guides are blinds guides, whether they live in the first century or the twenty-first. And one of the most destructive effects of a blind guide is that he kills in his followers the desire to carry on the search for Truth, Purpose, and Meaning.

Yet the search will continue, for we are by nature puzzle-solving creatures driven to connect the signs. The Lord knows that, and that is why he sends us detective-monks and monk-detectives, even skeptical ones, to help inspire us to seek for that divine order which is written indelibly, if sometimes obscurely, in the Book of Nature and the Word of God. •

Louis Markos , Professor in English and Scholar in Residence at Houston Baptist University, holds the Robert H. Ray Chair in Humanities. His 19 books include Lewis

Agonistes; Restoring Beauty: The Good,

the True, and the Beautiful in the Writings of C. S. Lewis; On the Shoulders of Hobbits: The Road to Virtue with Tolkien and Lewis; and From A to Z to Narnia with C. S. Lewis.

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS

full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone

online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

32.2—March/April 2019

The Problem of Pity

Misguided Mercy & Dante's Infernal Purgation by Joshua Hren

24.1—January/February 2011

Secular Grendel

Ruminations on the Monstrous Envy of the Soul-Devouring State by Anthony Esolen

30.4—July/Aug 2017

Soul Comforter

on Emily Dickinson & the Source of Our Hope by Josh Mayo

more from the online archives

14.6—July/August 2001

What Women Need

Three Bad Ideas for Women & What to Do About Them by Frederica Mathewes-Green

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor

Support Touchstone

00