Book Returns

The Beat Escape

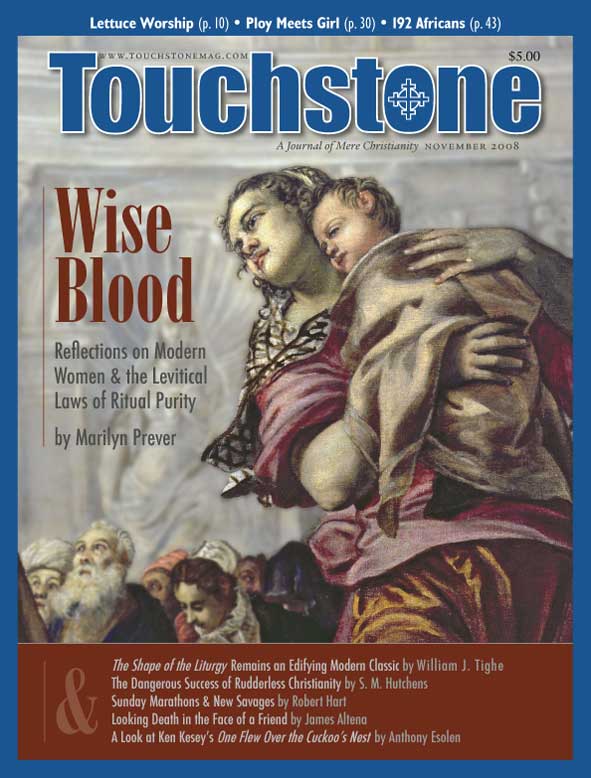

Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over

the Cuckoo’s Nest

by Anthony Esolen

The Big Nurse glares at McMurphy, the one man strong enough to dismantle the order of her mental ward. “I hope you’re finally satisfied!” she cries. Puddles of booze and broken bottles litter the floor. Her usually spotless uniform is splashed with blood; a shy young man named Billy has cut his throat in terror that the Nurse will tell her “old friend” his mother how he lost his virginity with a trollop. “Playing with human lives—gambling with human lives—as if you thought yourself to be a God!”

But McMurphy, an inmate sent to the ward from the penitentiary, has had enough of that whited sepulcher, that orderly wickedness. He smashes the window of her cubicle and rushes upon her, throwing her to the ground and nearly choking her life out, until one of the black orderlies clubs him from behind. He will never speak again in this world. When he returns to the ward, stilt-legged and open-mouthed, he will be as gentle as a lamb, and the scar of a lobotomy will crease his forehead from temple to temple.

That is the climax of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1962), the first novel by Ken Kesey, hailed by many as a great new writer. His style was compared to that of the comic strip, with typically exaggerated masculine characters (Steve Canyon, Spiderman) bursting through the conventionalities of a necktied modern world to slam the evildoers and protect truth, justice, and the American Way.

People wrote straight-faced articles about whether a trip on LSD, which Kesey and his fellows among the Beats dabbled in, was akin to a mystical experience, breaking the bonds of “imperialist rationality.” Tom Wolfe called their movement a Neon Renaissance. Others wrote about the novel’s symbolism of the West, the last refuge of man’s freedom from civilization; a kind of dry-gulch Mississippi for long-legged Hucks and their black or Injun companions.

The novel was, in part, all these things. It was detested by the feminists, and not entirely without justice; its portraits of women are juvenile caricatures. Yet they also inveighed against it because, as one said, “it never once challenges the completely inhuman sexist structure of society.”

No, that it didn’t. And that, strangely enough, is a key to whatever enduring value the novel has. It did not challenge the traditional roles of the sexes; it accepted them as beautiful. It did challenge what Philip Rieff would call the “therapeutic society,” our soft, soulless world of half-men and half-women who cannot break free of their need for padding and pills and self-analysis. It is a cry for independence, not political but personal, from the bureaucratic tyranny of help.

Deeply Conservative

Cuckoo’s Nest is a good book, not a great book. Its dialogue strikes many false notes; sometimes McMurphy sounds as if he’s read Marcuse, and sometimes the chat of the inmates is motivated not by character but by Kesey’s need to push a point or advance the plot. Its symbolism teeters between the bold and the bombastic. Kesey never became a great writer, and LSD did not revolutionize the world, and free love has not knocked the chains from our feet.

But only a lapsed Catholic like Kesey could have written Cuckoo’s Nest, which, when you strip away the nonsense of the age, is deeply conservative, proclaiming the sacramentality of humble and elemental things: fishing on a river, the cold of an Oregon night, the warmth of the human body, the boldness of man and the tenderness of woman.

The plot is straightforward, related by one of the inmates, a schizophrenic Indian, “Chief” Bromden. Into the smoothly run mental ward, that boast of the “helping professions,” comes McMurphy. He is quick to note that the Big Nurse, the power in the place, has cowed the ineffectual doctors and has maneuvered the “Acute” patients into submissiveness and treachery, rewarding the men for revealing one another’s fears and falls. All of this occurs in the context of group discussion and “therapy” and “democracy.” The “Chronics,” as they are called by the nurses and doctors, or “vegetables,” as they are called by the malicious orderlies, are wrecks of men, strapped upright in the daytime with tubes mastic-taped to their organs, yet standing in puddles anyway. It is a place where cruelty enjoys the spice of benevolence.

Anthony Esolen is Distinguished Professor of Humanities at Thales College and the author of over 30 books, including Real Music: A Guide to the Timeless Hymns of the Church (Tan, with a CD), Out of the Ashes: Rebuilding American Culture (Regnery), and The Hundredfold: Songs for the Lord (Ignatius). He has also translated Dante’s Divine Comedy (Random House) and, with his wife Debra, publishes the web magazine Word and Song (anthonyesolen.substack.com). He is a senior editor of Touchstone.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more from the online archives

23.6—November/December 2010

Darwin, Design & Thomas Aquinas

The Mythical Conflict Between Thomism & Intelligent Design by Logan Paul Gage

33.1—January/February 2020

Do You Know Your Child’s Doctor?

The Politicization of Pediatrics in America by Alexander F. C. Webster

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor