Sexual Colonization

How the Sexual Revolution Dehumanizes Everything

One of the great cultural and social shifts of the second half of the twentieth century was the dramatic and profound transformation in sexual mores that quickly came to be known as the “sexual revolution.” At the time, sociologists tried to explain it as the result of various factors like the “Pill,” economic prosperity, the changed status of women, and so on. Many people, of course, discussed its moral significance, either as an explosion of libertinism that threatened the foundations of society (the “conservative” view) or as a liberation from the vestiges of “Victorian” morality (the “liberal” view). However, relatively few authors analyzed the sexual revolution from a philosophical angle, meaning neither sociologically nor ethically, but in terms of its metaphysical presuppositions and its place in the history of ideas.

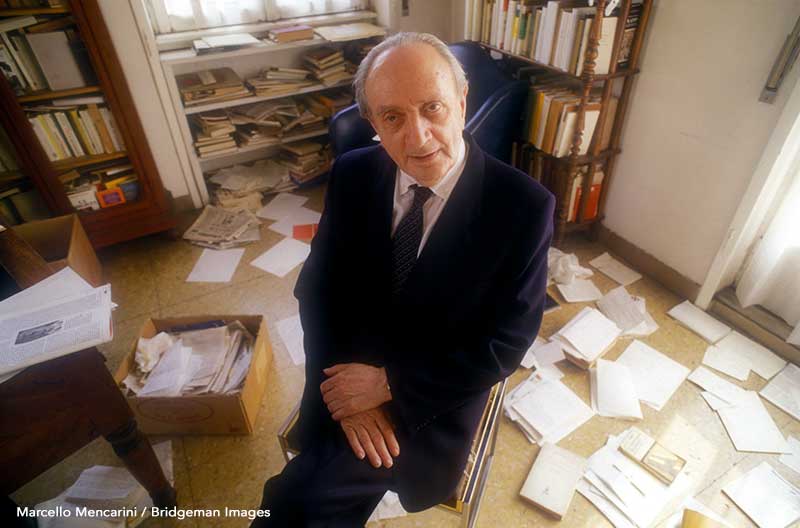

A notable thinker who raised the question of the philosophical significance of the sexual revolution was Augusto Del Noce, a prominent Italian Catholic philosopher and political thinker who died in 1989. Del Noce became convinced that the sexual revolution could only be explained as the result of a deeper and broader culturalshift, namely, a radical transformation of our culture’s vision of what it means to be human, of our “philosophical anthropology.”

In fact, according to Del Noce, this shift should not even be described as a transformation of our view of human nature, because one of its constitutive elements is precisely the negation that there is a specifically human nature. This negation coincides with the negation of what the French cardinal and theologian Jean Daniélou called the “religious dimension,” meaning the fundamental human ability to ask religious questions, our innate aptitude for transcendence.

In this essay I would like to outline Del Noce’s analysis of the nexus between the suppression of the religious dimension (rather than of any particular religious tradition) and the triumph of the sexual revolution, including its aspect of producing (in the words of Pope Francis) a form of “ideological colonization.” Obviously, in an article I cannot do full justice to Del Noce’s thought, but I hope to give readers a taste of it. I will draw in particular from two collections of essays, titled The Crisis of Modernity and The Age of Secularization, which I edited and translated.

The Cultural Context of the Sexual Revolution

Del Noce’s analysis of the sexual revolution is inseparable from his diagnosis of the context in which the revolution started and progressed: Western culture at large in the two decades after World War II. Before the war, mainstream secular culture had largely failed to predict and prevent the rise of totalitarianism. After the war, it faced the double threat of Soviet communism and a rebirth of religion. It exorcised these dangers, broadly speaking, by rediscovering the ideas of the eighteenth-century Age of Enlightenment, and by repudiating the “Romantic reaction” that had prevailed in the nineteenth century and had still marked European culture in the first half of the twentieth.

By “Enlightenment” Del Noce means the rationalist emphasis on scientific and technical reason—the tool that enables humanity to leave behind the “dark ages” and enter “adulthood”—and also the rejection of religious and national traditions in favor of a secular and cosmopolitan culture. He describes the “confused but extremely widespread disposition” among scholars, journalists, and artists of the generation that came of age around 1945. Following the horrors of the war and the Holocaust, they rediscovered the Enlightenment as

a disposition to declare a break with traditional structures and criticize them inexorably from an ethical, political, and social standpoint. . . . This disposition is a mixture of a millennialist element—as if a great cosmic revolution had destroyed old Europe-turned-into-Babylon with its traditions and values—and an Enlightenment element pointing to the only philosophical road that can still be followed. . . . Therefore, emancipation from authority and traditions in the spirit of the Enlightenment had to take place according to the aspect of the Enlightenment that makes negation its dominant character.

This widespread anti-traditional sentiment among the intellectuals was reinforced by another rediscovery: that of Marxism, which also came back in vogue, especially in continental Europe, after World War II. According to Del Noce, “the rebirth of the mindset of the Enlightenment and the rediscovery of Marxism have met and compenetrated each other,” with the result that Marx was rediscovered in his scientistic and materialistic aspects, while his Romantic and revolutionary aspects were downplayed.

Del Noce points out that Marxist materialism in isolation (separated from belief in the revolution) leads to “total relativism,” because if all values are reflections of historical circumstances, they lack permanent validity. Then the study of human realities is entirely entrusted to social scientists, who are able to measure how different material factors shape the life of society.

Accordingly, in the post-war period, the rediscovery of Marxist ideas manifested itself as a “hubris of the human sciences, hubris in the sense that they want to replace philosophy [with] sociology, psychoanalysis and, particularly today, structuralism.” The human sciences claimed jurisdiction on the human sphere in an ongoing quest to “dissolve man by reducing him to a purely natural reality: after having been analyzed by structuralism, the spirit will reveal its nature as a thing among other things.” Del Noce calls this Marxist-inspired hubris “sociologism, the form of thought that today is the philosophical justification for the most a-religious and also most conservative society that ever existed, the so-called affluent or consumerist society, or society of well-being.”

Undoubtedly, the embrace of “scientism” (the one-sided exaltation of science as the only valid form of knowledge, and the replacement of philosophy by the human sciences) on the part of secular culture took place somewhat differently in Europe than in the U.S. For one thing, in Europe it required a sharper break with the past, while American culture was probably more predisposed to it.

Not by chance, in post-war Europe “America” became the symbol of a science-oriented, pragmatic, forward-looking culture freed from the constraints of tradition. In 1943, after visiting New York and shortly before dying, Simone Weil described the possible triumph of scientism as the “Americanization of Europe” and as an “involuntary invasion” by an America which, in turn, had been deprived of its own past by Europe’s catastrophe, because “Americans have no past except our own.” Conversely, in the U.S., the influence of Marxism was certainly more indirect, and took place mostly through the human sciences.

The end result, however, was the same: a combination of ideas dating back to the Enlightenment and of Marxist ideas led secular culture to embrace what could be called “scientistic progressivism.”

Two Visions of Humanity

Now, what is, precisely, the “enemy” of scientistic progressivism? Is it the past in general? Religious tradition? Authoritarian morality? Del Noce argues that in the history of ideas we can identify a philosophical tradition that characterizes Western culture and which is denied by the “new Enlightenment.” He calls it “Platonism in the broadest possible sense” and describes it with the concept of participation.

In classical Greek and Christian philosophy, the word “participation” refers to the idea that all human beings participate in a universal and divine reason, the Logos: “Man possesses in himself an agent whose essence is divine, and this agent and the power that eternally shapes and organizes the world are ontologically, or at least in their principle, one and the same; hence reason’s aptitude at knowing the world.” Traditionally, Christian thinkers have often perceived a consonance between this Platonic notion and the biblical doctrine of the imago Dei, the image and likeness of God, which distinguishes man from all other creatures.

This view of humanity as “participating” in the nature of God—and thereby having a specific “human” nature distinct, for example, from a purely animal nature—was for centuries universally accepted. Over time, though, it “incurred the greatest misfortune that can befall an idea: it became an unquestionably evident truth, something taken for granted,” and now it is finally being overturned.

All contemporary conflicts, be they philosophical-religious or political, boil down to the opposition between the Platonic-Christian idea of man as image of God and the instrumentalist conception. According to the former the human mind thinks by participation (however understood) in the divine truth, so that Truth and Goodness remain absolutely the same for all peoples and all social classes by virtue of this participation. The latter regards man as an animal that uses signs (language) and makes use of instruments in order to transform the world—signs, words, and concepts being precisely just instruments for this purpose.

This opposition between “the instrumentalist conception of the mere humanness of ideas versus the tradition of participation in the Logos” determines tworadically irreconcilable philosophical anthropologies. Del Noce refers to German philosopher Max Scheler’s distinction between homo sapiens, “who is characterized by his participation in the Logos,” and homo faber, who is defined by his power to manipulate reality.

When the former is replaced by the latter, this “replacement leads to the negation of the idea that there is a human nature and to the affirmation that praxis is the measure of truth. . . . This then leads to the supremacy of power, in all its manifestations.” The negation of human nature as distinct from animal nature, is followed by various other negations, such as the negation of the very idea of tradition as the handing down of eternal truths and values, and the radical negation of authority as distinct from power.

Most importantly, the negation of participation in the Logosand the affirmation of purely instrumental reasongo hand in hand with the negation of what Del Noce (again following Daniélou) calls the “religious dimension”:

By religious dimension . . . I mean just the following: that there is an eternal and unchangeable order of truths and values, which we can come in contact with through intellectual intuition. In short, that there is a super-human reality, no matter how diverse may be the ways of signifying it. Before the advent of the technological mindset that has reached today the climax of its explication, all peoples agreed to this. And, on the other hand, how could man receive the light of the true faith if nothing had been left in him of this primitive revelation, even after sin?

The religious dimension is not faith and is not even “Christian in the proper sense. Rather, it is the precondition that makes it possible for the act of faith to germinate in man, inasmuch as it is man’s natural aptitude to apprehend the sacred.” In this sense, it is akin to the notion of “religious sense” which in Italy, a few years before Del Noce, had been discussed in a pastoral letter by Cardinal Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI. Also in Italy, it was the subject of The Religious Sense, a well-known book by Catholic theologian and educator Monsignor Luigi Giussani.

The fact that, at about the same time, these different authors came to recognize the question of the religious dimension, or religious sense, as crucial to responding to secularization is significant. In Daniélou’s words, “The religious dimension is the question to which revelation is the answer.” While, in ages past, the answer had been challenged, now the question itself was under attack. The new scientism, Del Noce says, “due to its professed relativism about values . . . replaces a direct struggle against religion with an indirect one and thereby endangers religion even more, because it erodes the religious dimension until it erases from consciousness all traces of the question of God.” In an essay on French author Simone Weil he explains:

Until recently, one could say that faith was under threat, rather than religion. Idealistic philosophies claimed to sublate the truths of faith into a higher form of religiosity. Marxism itself, in its own way, wanted to satisfy the need for the other reality, although it projected this reality within time. What is in question today, by contrast, is the religious dimension. Official religious thought does not have a sufficiently clear awareness of this change. In fact, there [are] plenty of theologians who think of adapting faith to a world that they regard as permanently de-sacralized and made secular by scientific and technical progress. Faith, they say, must listen to the world. . . . But how can faith be welcomed by a world that regards the religious question as meaningless?

The Sexual Revolution & Secularization

The opposition between the two visions of humanity that I have described provides the philosophical framework for Del Noce’s assessment of the sexual revolution. In an essay titled “The Ascendance of Eroticism” he scathingly criticizes people (especially Christians) who think they are facing a mere variation in society’s sense of modesty, a loosening of morals due to affluence, technological advances, the new status of women, etc. Without denying the importance of these factors, he deems them insufficient to explain the scale, the radicalness, and the apparent irresistibility of the phenomenon.

Sexuality is so closely tied with human affectivity and the deepest human aspirations that a culture’s view of it is the most concrete and most revealing translation of that culture’s view of humanity. To Del Noce, the contrast between traditional sexual morality and the “mass libertinism” of the modern West reflects precisely the contrast between the Platonic-Christian idea of homo sapiens and the instrumentalist idea of homo faber.

In order to illustrate this connection, he refers to twentieth-century Austrian doctor and psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich, as the first author who explicitly linked the idea of sexual liberation with the negation of the religious dimension. In his most famous book, which is appropriately titled The Sexual Revolution, Reich advocated for the abolition of all “finalistic, idealistic concepts,” and he identified the full realization of human life with “sexual happiness” defined by “science.” Del Noce explains:

Reich’s thought is based on the premise, which of course is taken as unquestionably true without even a hint of a proof, that there is no order of ends, no meta-empirical authority of values. Any trace not just of Christianity but of “idealism” in the broadest sense, or of a foundation of values in some objective reality, like history according to Marx, is eliminated. What is man reduced to, then, if not to a bundle of physical needs? When these needs are satisfied—when, in short, every repression is removed—he will be happy. . . . Having taken away every order of ends and eliminated every authority of values, all that is left is vital energy, which can be identified with sexuality, as was already claimed in ancient times and is actually difficult to refute. Hence, the core element of life will be sexual happiness.

The close connection between the sexual revolution and scientism cannot be emphasized enough. The scientistic will to expunge from the sphere of rationality everything that escapes immediate empirical verification leads to a radical form of positivism, in which human realities lose all symbolic significance and become “dumb,” in the sense that they no longer speak to us of anything beyond themselves.

The relationship of difference and complementarity between the sexes no longer participates in any ideal order or any deeper archetypal reality, such as, in Christianity, the spousal relationship between Christ and the Church. The question of the significance of the marital act is voided a priori by the fact that nothing is significant because nothing is a sign. Sexuality, childbearing, motherhood, fatherhood, the human body itself: all these realities are denied any ideal or universal value and are reduced to pure facts among other fundamentally meaningless facts, which “science” counts and catalogs.

Therefore, any hierarchy of preferences is absurd, and potentially violent. Everything is what it is: sexual urges are what they are; feelings are what they are; “love is love”; and all such things point to nothing beyond themselves. They are just ends in themselves, or better, they are instruments to achieve the one end of “well-being.”

Some people have argued that the sexual revolution marks the triumph of subjectivism, but in fact its deeper impulse is towards universal objectification. From a scientistic perspective, feelings, instincts, and orientations are taken to be brute facts that cannot be measured against any transcendent criterion or freely called into question. More than subjectivism, the resulting attitude is emotivism or instinctivism, the affirmation of a purely instinctual idea of freedom.

So, reversing Nietzsche’s quip that Christianity is Platonism for the masses, sexual liberation is functionally positivism for the masses, or, as Del Noce also says, the tool to turn peoples into masses by uprooting them from their ideal/symbolic/sacramental humus. It achieves among common people what the atheistic philosophers of the nineteenth century and the revolutionaries of the twentieth had not been able to achieve outside relatively small circles of intellectuals and activists: the suppression of the religious dimension. Not only must today’s process of secularization be understood primarily as a process of erosion of the religious sense, and only subsequently as a loss of faith, but sexual liberalization must also be recognized as its Trojan horse.

To further illustrate this point—that the religious dimension is the true target of Western secularization, and in particular of the ideology of the sexual revolution—allow me to quote a passage from Wilhelm Reich’s The Sexual Revolution, in which we find possibly the earliest appearance of an idea that has since become very common. Reich almost never talks about the Church, but here he proudly throws down the gauntlet, and he pronounces what he thinks is the final and irresistible challenge to Christianity:

Religion should not be fought, but any interference with the right to carry the findings of natural science to the masses and with the attempts to secure their sexual happiness should not be tolerated. Then it would soon be apparent whether [or not] the Church is right in its contention of the supernatural origin of religious feelings.

What is most significant about this is that it is a sexualized, but perfectly recognizable, version of Marx’s theory of false consciousness. Marx famously claimed that religious beliefs are just consolatory delusions that people create because they are exploited and oppressed; these delusions will therefore vanish after the triumph of the communist revolution. The difference with Reich is that instead of applying this idea to the economically oppressed, he applies it to the sexually repressed. “Religious feelings” are false images of sexual desires, so once the sexual happiness of the masses is secured by the application of “natural science,” the false desires will disappear. In the Reichian utopia, the vanishing of religion will not be the result of direct persecution, but of the disappearance of religious questions (i.e., the religious sense) among a sexually satisfied populace.

The manner in which the combination of scientism and sexualized Marxism leads, in Reich, to the denial of the religious sense is truly paradigmatic of the sexual revolution as an epochal phenomenon, meaning a phenomenon that marks an epoch (ours) and reveals its deepest metaphysical assumptions. It also points to the way in which this epoch can, and will, end: by a rediscovery of the full scope of human desire, of its “infiniteness.” This will include a rediscovery that the religious sense is at work within every particular desire, so much so that, pace Dr. Reich, even sexual desire has a religious dimension which can be denied only at the price of either unbearable boredom or spiritual derangement.

Sexual Revolution & Ideological Colonization

In conclusion I would like to offer some remarks on the concept “ideological colonization,” which has been recently in the news. It refers to the attempts by Western elites to export their “progressive” sexual morality to the rest of the world, for example, by tying foreign aid to the liberalization of abortion or the institution of same-sex “marriage.” In 1970, speaking of the intellectuals who believed that the Cold War could be won by embracing material affluence, sexual liberation, secular democracy, and so forth, Del Noce wrote:

Colonization can be achieved by only one method: by uprooting a people from its traditions. Europeans have a long history of extensively practicing this method (and this was Europe’s greatest historical fault). Now—oh, wonder!—in order to feign regret they are applying the same method to themselves.

This comment points to a peculiar fact: in recent decades the primary target for colonization by Western intellectual, economic, and political elites has been their own peoples. We may well be the first culture in world history that is keen on uprooting itself, in a process that could aptly be described as “self-colonization.”

This makes contemporary Western relations with other cultures very different from traditional forms of colonialism. For sure, European colonialists of the nineteenth century did not hesitate to uproot peoples from their traditions in the name of science, progress, modernity, and similar constructions they had inherited from the eighteenth century. However, they generally regarded themselves as the bearers of their own, more advanced and more humane civilization. The nineteenth century was, after all, the century of the Romantic “reconciliation with the past.” Conversely, the new Enlightenment can “export” only its process of self-disintegration. It tries to force on other peoples not a culture but the negation of a culture.

What is worse, the target of this negation is, as I have tried to demonstrate, the religious dimension, which all traditional societies rightly view as the foundation of their civilizations. Undoubtedly, these two factors—pure negativity and anti-religiosity—make today’s Western cultural colonialism especially ruthless and destructive. However, they also make it weak, in the sense of being intrinsically unable to build and hold. After all, empires cannot be built just by dissolution, let alone dissolution of one’s own culture.

Back in 1971, Del Noce conjectured that the relentless expansion of what he called “Occidentalism” would lead to the highest degree ever of both “world unification and colonialism,” but at the price of the social disintegration of the West itself. Half a century later, his vision has proved prophetic. Now the question is what will fill the desolation when Europeans and Americans are finally done waging what he dubbed “the Enlightenment’s war against their own past.”

—This essay is a modification of a talk delivered at the 2018 conference of the John Paul II Institute for the Study of Marriage and Family, “The Body as Anticipatory Sign: Commemorating the Anniversaries of Humane vitae and Veritatis splendor.”

Carlo Lancellotti is Professor of Mathematics at the College of Staten Island of CUNY and a faculty member in the Physics Program at the CUNY Graduate Center. He has translated three volumes of works by Augusto Del Noce, the late Italian philosopher and political thinker.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on biographical from the online archives

more from the online archives

23.6—November/December 2010

Darwin, Design & Thomas Aquinas

The Mythical Conflict Between Thomism & Intelligent Design by Logan Paul Gage

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor