Babylon's Furnace

Truth, Suffering & the Hard Road Ahead

When I try to explain the Benedict Option concept to people, I tell them that we Christians today are called to live between Jeremiah chapter 29 and Daniel chapter 3. In the former, God speaks to his captive people Israel, telling them that he has delivered them to Babylon for a time, and that they are to settle down in Babylon, take wives, plant gardens, and "seek the peace and prosperity of the city to which I have carried you into exile." I believe that holds true for Christians living in this latter-day, post-Christian Babylon.

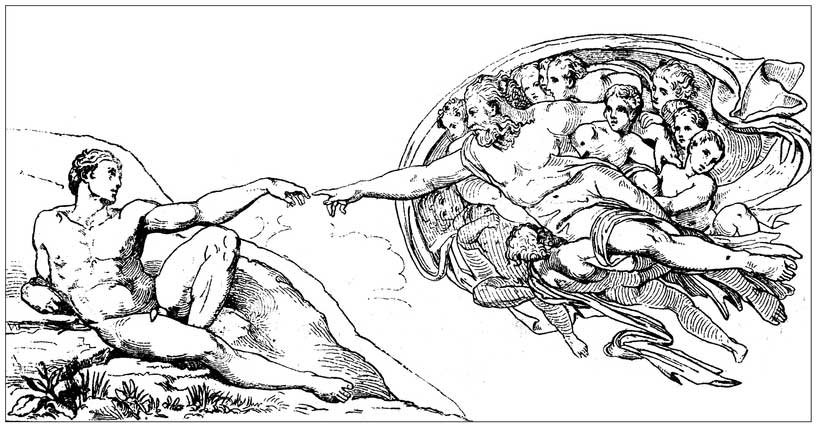

But consider also the story from the Book of Daniel, of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego. Those three Hebrew captives held high positions in the government of King Nebuchadnezzar. But when they refused to bow down to worship a false idol constructed by the king, he threw them into a fiery furnace. As we know, the fire did not consume them. This miracle changed the cruel king's heart.

What was it about the way that Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego lived in Babylon that gave them the presence of mind and the courage to resist, even at the potential cost of their lives? Think about it: you can't get much more embedded in the life of Babylon than to serve the king, but these three Hebrew men always knew who their ultimate Lord was—and were prepared to die for him.

So my message to Christians today is that we urgently need to figure out a way to live embedded in our latter-day Babylon so that we always know who our true Lord is. We need to live so that we are able to see clearly when we are asked to betray him—and so that we have the courage to refuse, no matter what it costs us.

I am 54 years old. For all of my life, talk of anti-Christian persecution in America has been reserved primarily for speculative fiction of the "Left Behind" variety. Those days are over. Christians today have to prepare themselves to face real persecution. America is not the country it once was. In this paper, I am going to speak of the forms anti-Christian persecution is likely to take, and how we can prepare ourselves for the worst—even to go into Babylon's furnace, if that's what the Lord asks of us.

This is not going to be a cheerful, optimistic presentation. But it is going to be a hopeful one. I'll explain that at the end.

An Alarm Sounded

Five years ago, I received a phone call from an American physician, who was rather alarmed. He told me that his mother had emigrated to America from Czechoslovakia. When she was young, she served six years as a political prisoner because she was part of the underground Catholic resistance to communism. Now, as an old lady living with her son and his wife, she said to her son, "The things I am seeing in this country today remind me of when communism came to my homeland."

She was talking about the growing intolerance, even hysteria, from the Left against anything that conflicts with their ideology. I knew that political correctness was a big problem, but this sounded exaggerated to me. Maybe she is just a frightened old woman, I thought.

But over the next few years, I began talking to immigrants from the Soviet bloc—men and women who once lived with communism but later escaped to the West. I would ask them, "What are you seeing today? Is this old Czech woman correct?"

Over and over, I heard the same thing: YES! It really is happening here. We can feel it in our bones. Almost all of them are quite frustrated and angry that no American believes them.

I understand the skepticism. I was skeptical, too, when the doctor first called me. Today, though, after interviewing a number of these people, and spending much of the last year traveling through the former communist countries of the East to interview former dissidents and political prisoners, I am convinced that they are right. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn said, "There always is this fallacious belief: 'It would not be the same here; such things are impossible.' Alas, all the evil of the twentieth century is possible everywhere on earth."

It is not only possible here in the liberal democratic West, but it's taking form right now. People who lived through communist totalitarianism are trying to sound the alarm.

The New Totalitarianism

Before we go further, let's define our term. What is totalitarianism?

It's a term from the twentieth century—Mussolini invented it, in fact—describing a society led by a single political party. No political opposition is allowed. That is what we call "authoritarianism." Authoritarian regimes only really care about monopolizing political power. What distinguishes them from totalitarian regimes is that, under totalitarianism, everything is political. There is no escape from the ruling ideology.

Authoritarian regimes only want your obedience. Totalitarian regimes want your soul.

We are living through the emergence of what I call "soft totalitarianism." It is emerging from a condition of mass alienation and loneliness, and a collapse of trust in hierarchies and authorities—the same things that Hannah Arendt identified as the principal reasons for the emergence of communism and Nazism in the twentieth century. Wokeness—the slang term for the ideology of soft totalitarianism—does not come from nowhere.

The immigrants who lived under communism understand wokeness as totalitarian because they know what it's like to live in a society in which people lose their jobs, their reputations, and even their freedom if they do not affirm the ruling ideology. The rest of us don't see this, in part because we think totalitarianism can't happen here. We also miss it because our idea of totalitarianism is formed by the experience of communism, and by George Orwell's 1984. In that novel, the totalitarian state enforced its ideology through pain and terror.

We don't have that now. Rather, the form of totalitarianism emerging in the West today is more like the alternative dystopia imagined by Aldous Huxley in Brave New World. Huxley imagined a world where the state controlled the masses by managing pleasure and comfort. In his novel, the state exists to liberate the human being from suffering. Mustapha Mond, the world controller for Europe in the story, describes the system as "Christianity without tears." It is Christianity without the Cross. The dissident figure, John the Savage, rebels because he believes suffering is intrinsic to human nature. He accuses the system of abolishing man by attempting to eliminate suffering. But is it any wonder that American Christians, conditioned as we have been to the therapeutic mindset, fail to perceive the totalitarian nature of wokeness?

Western people will surrender political power to a state (and to authorities) that promises to protect and promote their therapeutic desires—especially maximizing sexual freedom. A state will do this through some version of China's social credit system, where a person's freedom in society is decided by an algorithm that rewards or punishes individuals based on their beliefs, their friends, and so forth. As in Brave New World, the most important values will be "safety" and "well being." If religious and political liberties threaten either, they will have to be eliminated. This is already happening in universities and other institutions that, in a very Soviet way, are stigmatizing dissent as pathological.

American social critic James Poulos calls the form that the new totalitarianism is taking the "Pink Police State." It entails the government, academic and cultural institutions, and large corporations. In fact, the new totalitarianism is not primarily imposed by the state. It is being imposed by all the major institutions of American society—big business, academia, the media, sports, law, medicine, even the military—which have accepted wokeness. We are now living through the experience of how a totalitarian ideology can emerge within a liberal democracy, and parasitically inhabit its institutions.

What We Have to Do

So how do we resist? The good news is that there are people who retain living memory of communist totalitarianism. They have seen this kind of thing before. They are warning the rest of us that we are walking into a trap.

I hope and pray that we can turn this back. But the Church cannot afford to be optimistic. In The Benedict Option, I wrote in a general way about how we Christians should live as creative minorities in a post-Christian world. I wrote about how all of us mere Christians should return to roots and traditions and embrace a life of spiritual discipline in community. Father Cassian Folsom, the founding prior of the Benedictine monastery in Norcia, St. Benedict's Umbrian hometown in Italy, told me that no Christian family that hopes to get through the trials ahead will make it without some form of the Benedict Option.

My book Live Not By Lies is an extension of The Benedict Option, but more narrowly focused. It is about how to live faithfully under active persecution, according to the advice of Christians who stayed behind in the Soviet bloc. What do they tell us we have to do?

• First, we have to prefer nothing to the truth. We have to make living in truth the bedrock of our lives, and accept the consequences of that. Father Kirill Kaleda, a Russian Orthodox priest, told me about how he and his siblings knew that under the Soviet system, they would not be able to follow any career path. Many careers required burning a pinch of incense to the Bolshevik Caesar—and this is something Christian families could not do.

Father Kirill said it was difficult, but there was no choice for honest men and women: "People understood that if it was going to be a priority to live in truth, then they were going to have to limit themselves in other ways. They made a choice, and resolved to live by it."

But this choice can be a public witness that changes the world. Vaclav Havel, the playwright who became the first president of a free Czechoslovakia, published an essay in 1977 titled "The Power of the Powerless." In it, Havel, who was not a Christian, said that the power of sacrifice for the truth could change the world. Consider, he said, a greengrocer running his shop in a communist city. Like all the other shop owners, he hangs a sign in his shop window proclaiming the Marxist slogan, "Workers of the world, unite!" None of them believe it; they hang the sign to avoid trouble.

What happens if, one day, the greengrocer decides he's tired of living in lies, and takes the sign down? The secret police come. They take away his business. He and his family lose privileges. He becomes something of an outcast.

What has the greengrocer gained, though? He has shown that it is possible to live in truth, if you are prepared to accept suffering. If more people are moved by his example to do the same, the system built on lies will eventually not be able to stand.

• Second, we have to reclaim and defend cultural memory. When the Nazis invaded Poland, their ultimate plans were not simply to rule Poland, but to destroy the Polish nation. They sought to do this the way all totalitarians do: by controlling the cultural memory of the Polish people. They had to make the Poles forget their history, and forget their religion.

A young Polish actor, Karol Wojtyła, committed himself to the patriotic resistance. But he didn't pick up a gun! He and his theater friends wrote and performed underground plays on religious and historical themes. These theatrical events happened in secret. If the Gestapo had discovered them, all the actors and audience members would have been shot. Wojtyła and the theater company literally put their lives on the line to keep alive the cultural memory of their nation.

We have to do the same in our time. The attempt to demonize the past is a strategy of domination. The communists did the same thing, as do all totalitarians. People who know who they are, are harder to control. In communist Prague, dissidents organized seminars and lectures about art, literature, and all the aspects of culture being denied or dismissed by the totalitarian government. These weren't simply ways to entertain people through the tedium of communism. These seminars were strategies of cultural and national survival. They were to remind the Czech people who they were.

We should not assume that the state is the only eraser of cultural memory. Our consumer capitalist society is an even more effective way of destroying cultural memory. In Budapest, a teacher I interviewed told me with sadness that in the three decades since the fall of communism, consumer culture destroyed more cultural memory than the communists had managed to do. In the same way, many Catholics in Poland told me that they expect Poland to go the way of Ireland, to a rapid collapse of the faith, in large part because the post-communist generation has been culturally catechized by the godless, hedonistic West.

• Third, we must establish and defend solidarity. I am not talking specifically about the Polish trade union. I am talking about something more intimate: the bonds among small groups of people.

In every post-communist country I visited, I heard the same thing from former dissidents: that the strong bonds of solidarity with others gave them the courage to fight back. In 2019, I stood in a secret underground room in Bratislava, where Catholic samizdat was printed for a decade. My guide was Jan Simulcik, a historian who in the 1980s was part of the underground network that distributed that samizdat. He told me that, like everybody else in the movement, he was afraid—but the camaraderie of his friends gave him the courage to keep going.

Dr. Vaclav Benda, a hero of the Czech resistance, worked to bring Czech people together, face to face, to remind them that they were actually a people. The state demoralized the masses by making them feel isolated and alone. As Dr. Benda saw, the simple act of rebuilding social solidarity was counterrevolutionary. In our time, the state doesn't force us to choose loneliness and isolation behind a glowing screen; we do it to ourselves. We can fight back by rebuilding the bonds of community in practical ways.

The dissidents told me that we have to establish sacrificial relationships with other dissidents—those from other churches, and those outside the Church. Kamila Bendova and her husband Vaclav were the only Christians inside the senior circles of the Czech resistance. I asked her if she and her late husband found it hard to work closely with Havel and the other hippies in the resistance, given their rather lurid sex lives. Kamila told me they understood that, under totalitarianism, courage was the rarest quality. Very few people had it. Most Christians behaved like everybody else: they put their heads down and conformed to avoid trouble. So when you found someone who had the courage to stand up and speak out against the evil order, that person had to become your best friend, no

matter what.

Those are wise words. Moreover, the dissidents' prison experience taught them something about what we in Touchstone circles call mere Christianity. They discovered that they weren't in prison for being Protestant, Catholic, or Orthodox. They were in prison for being Christian. That is how it will be with us, too. We need to get that clear right now.

• Fourth, we must strengthen our religion. I don't simply mean that we must go to church more. We have to be far more radical than that. In The Benedict Option, I write about St. Benedict of Nursia, the sixth-century Christian who responded to the collapse of the Roman imperial order by creating a parallel society dedicated to disciplined prayer and service to God. Over the next few centuries, the Benedictine monks played an absolutely key role in civilizing barbarian Europe. It began, though, with St. Benedict developing a Christian way of life that was resilient in the face of the extraordinary stresses of the early medieval period.

Last year I made a pilgrimage to the cave in Subiaco where Benedict lived alone for three years as a hermit, praying and fasting and seeking the will of God. From that little hole in the side of a lonely mountain grew a seed of faith that, over the next centuries, would rebuild Western civilization. If you feel powerless and despairing, go to Subiaco and see what God can do with a single man who puts the search for him above everything else.

We now live in a post-Christian civilization. Right now, while there is time, Christians at the local level must commit themselves to creating new ways of living out old truths. Every one of the anti-communist dissidents I interviewed was a strongly believing Christian. Pawel Skibinski, a biographer of Pope John Paul II, told me that humanity is like a kite. As long as it is connected to the earth by a string, it can fly very high. But if the line is cut, the kite falls to the ground.

We are the kite. The line is our connection to God. Without the God of the Bible, we will not be able to resist either the coming totalitarianism or the parallel temptation to embrace evil forms of resistance. Either we will be fully committed to our faith, or we will apostatize under pressure. There really is no neutral ground.

• Finally, we must embrace the value of suffering—the most counterrevolutionary thing of all. This strikes at the heart of the Pink Police State and its therapeutic totalitarianism.

If you are not willing to suffer the loss of social status; if you are not willing to suffer the loss of a job; if you are not willing to suffer the loss of comfort, freedom, and, if it comes to it, even your life, for the sake of the truth, then you have already surrendered to evil. This is the lesson we learn from the anti-communist resistance. The essence of their Christian hope was that suffering has ultimate meaning, if it is joined to the transformative Passion of Jesus Christ.

Two years ago, I sat in the lobby of the Hotel Metropol in Moscow, interviewing a former dissident named Alexander Ogorodnikov. He is in his seventies now, but in the 1970s, he was a young convert to Christianity who drew fellow disillusioned young people to prayer meetings in his apartment. Eventually the Soviets put him in prison. Because he came from a prominent communist family, they wanted to make an example of him. They put him on death row, with the worst of the worst.

Ogorodnikov shared the gospel with them. So many converted that the prison warden removed Ogorodnikov from the general population and threw him into solitary confinement. There the young Christian faced a deep crisis of faith. He felt abandoned by God. He didn't understand why God allowed him to suffer like that. Then, Ogorodnikov said:

I was alone in the chamber one night. I felt very clearly that someone woke me up in the middle of the night. It was soft, but clear. When I woke up, I had a very, very clear vision. I could see the corridor of the jail. I could see a person being taken out in chains; I only saw him from behind, but I knew exactly who it was. I understood that God sent me an angel to wake me up so I could accompany that man in prayer as he was being taken out to be shot. I understood that God was showing that to me.

"Who am I to be shown this?" I asked God. Then I understood that I was seeing the extent of God's love. I understood that the prayers of this prisoner and I, for his salvation, had been heard and that he was forgiven. I was in tears. This awakening didn't occur with all of those prisoners, only with some of them.

This kept happening, and it restored Ogorodnikov's faith. He understood that the Lord had allowed him to suffer so he could bring the gospel to those lost prisoners, some of whom would be in heaven for eternity because of his witness.

I can't emphasize strongly enough the countercultural importance of our orientation towards suffering. Let me tell you another story. Dr. Silvester Krcmery was a young Catholic physician who was a leader in the underground church in Slovakia. In the early 1950s, the secret police grabbed him off the street and threw him into prison, where he remained for a decade. Many years later, after communism's fall, Dr. Krcmery wrote a memoir about how he and the other Christians in that prison had come through with their faith intact.

Once again, we see that a Christian orientation toward suffering was the key. Dr. Krcmery said that he knew from the beginning that he could not allow himself to feel self-pity. If he did, he said, he knew he would collapse. Instead, he told himself that he was "God's probe" in that prison. What he meant was that the Lord had led him into that prison to be his spy. Rather than brood over "Why me?", Dr. Krcmery got busy witnessing to other prisoners, praying with them, and worshiping with them. He construed his suffering in prison as an opportunity to deepen his own repentance and to serve others.

The Right to Be Unhappy

A final story about suffering. When I was in Budapest in 2019 doing interviews for Live Not By Lies, my interpreter was a faithful young Catholic named Anna. She was a wife and the mother of a small boy. As we rode on a tram through the city, Anna told me how frustrating it was not to be able to relate to her friends. She said that when she tried to tell them about the problems she and her husband were having, or the struggles she had raising her little boy, her friends leapt to tell her that she should get a divorce and put her son in daycare. They told her, "You have to do whatever it takes for you to be happy."

Anna said they couldn't understand that she is happy. She loves being a wife and a mother, but life is not without its difficulties. These friends of hers—even Catholic ones—have the idea that suffering of any kind is to be refused, no matter what the cost.

I said to Anna, "It sounds like you are fighting for your right to be unhappy." "That's it!" she said. "That's exactly it! Where did you get that?" I pulled out my smartphone and went to chapter 17 of Brave New World. We read it together, and she saw that John the Savage, the dissident and the only sane man in his totalitarian world, admitted to the world controller that yes, he was fighting for his right to be unhappy.

This is the unappealing fact facing all Christians: in the face of soft totalitarianism, we are fighting for our right to be unhappy. It's not that misery is next to godliness—not at all! We are called to be joyful as Christians, but our idea of joy has to entail the joy of the martyrs, who were willing to give their lives for the joy of serving the Lord. As John the Savage argues, without the right to be unhappy—that is, if suffering is banished from the world—all things truly human dissolve.

We mere Christians in this anti-Christian civilization must immerse ourselves and our families in the stories of the martyrs and the confessors—from the early church and from the church of our own time. We have to rediscover that this is normal Christianity. Last week I spoke to an Evangelical friend who works with the persecuted church around the world. From his perspective, the American church is now joining history, and is going to discover what life is like for many Christians in this world today.

Our Kolakovic Moment

I want to close with a story about a hidden hero who deserves to be rediscovered. In 1943, a Croatian Jesuit named Father Tomislav Poglajen was organizing Catholic anti-Nazi resistance in his home country. When he learned that the Gestapo was going to arrest him, the priest fled to his mother's country, Czechoslovakia. He adopted his mother's last name, Kolakovic, and began to organize Catholic anti-communist resistance.

Why anti-communist resistance? Father Kolakovic knew that the Germans were going to lose the war. But as he told the young Slovak Catholics who gathered around him, communism would ultimately come to power in their land. And that, he prophesied, would mean horrible persecution for the Church.

Father Kolakovic did not sit around waiting for it to happen. Instead, he organized cells around the country—groups of young Catholics who gathered for prayer, Bible study, and lectures. They also learned the arts of resistance—for example, how to survive an interrogation. They established resistance networks across the Slovak region.

Now, the Slovak Catholic bishops hated this. They accused Father Kolakovic of being alarmist. They told him that what he worried about would never happen there. But the priest understood the communist mind better than the bishops did, and he continued his work. So when the communist dictatorship installed itself in 1948, Father Kolakovic's network was ready. It became the backbone of the underground church, which was the chief source of Slovak anti-communist resistance.

I firmly believe that we are in a Kolakovic Moment in the West today. Read the signs of the times. We have to use the liberty we have now to form these small groups, and networks of small groups, to prepare ourselves, our families, and our churches for persecution.

Admirer or Disciple?

I said at the beginning that this was not going to be an optimistic talk, but it would be a hopeful one. So where is the hope?

Well, consider that very few dissidents expected communism to end in their lifetime. They resisted communism because that was the right thing to do. As a young man, a Slovak mathematician and Catholic Christian named Vlado Palko went out onto the main square of Bratislava in 1988, to join a peaceful prayer vigil that was the first public anticommunist demonstration since the 1968 Soviet invasion. That demonstration was the spark that ultimately led to the Velvet Revolution the next year, the one that brought down communism.

Vlado told me, "I thought back then that communism would last for the next thousand years. The truth was, it did not. And that is something for us to hope for today."

This is true. But there is a deeper sense of hope to which we Christians must cling. Christian hope tells us that no matter what terrible things may come, the Lord is with us. The Lord is with us, and our suffering, if we offer it to him, has ultimate meaning. The Lord may use that faithful suffering to lead others to him, and even in some sense to redeem the world. We are all called to share Christ's Crucifixion with him. We cannot escape our cross. But carrying that cross out of solidarity with our Savior is to proclaim to the world its redemption.

This is the hope that led Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego to choose the fiery furnace over apostasy. They believed that God would save them—and he did. But we well know that countless martyrs were not miraculously saved from death. Was God not with them? Of course he was. Those precious souls won crowns of glory. Today the Church remembers the three Hebrew youths—but we also remember Polycarp and Perpetua of the early church. We also remember, from our own time, Jim Elliot, Franz Jägerstätter, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Maximilian Kolbe, John of Kronstadt, and the twenty Coptic martyrs decapitated by Islamists on the Libyan beach a few years ago. In the end, we will be vindicated. The beheaded are the ones on the heavenly throne in the Book of Revelation.

I say, with Frodo Baggins, that I wish this need not have happened in my time. And I accept Gandalf's counsel: "So do I, and so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us."

That we do. There is no neutral ground. There is no place to hide. Where are you going to stand when the persecutors come for you? In the film A Hidden Life, about Franz Jägerstätter, a Catholic martyred by the Nazis, an artist tells Franz that so many people admire Jesus. But Jesus did not call admirers; he called disciples. You can tell the difference between admirers and disciples when it comes to suffering. The admirers fall away, but the disciples stagger onward rejoicing in Christ.

Which one are you? Are you an admirer or a disciple? All of us will be put to the test. The answer we give in that future moment depends on the decisions we make today. Let us commit ourselves to making wise use of the time and the freedom that God has given us.

Rod Dreher is a contributing editor to Touchstone. He is a writer and blogger and the author of several books, including The Benedict Option (2017) and Live Not by Lies: A Manual for Christian Dissidents (2020).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

37.5—Sept/Oct 2024

Why Law Schools Can't Teach Law

A sidebar to How Law Lost Its Way by Adam MacLeod

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor