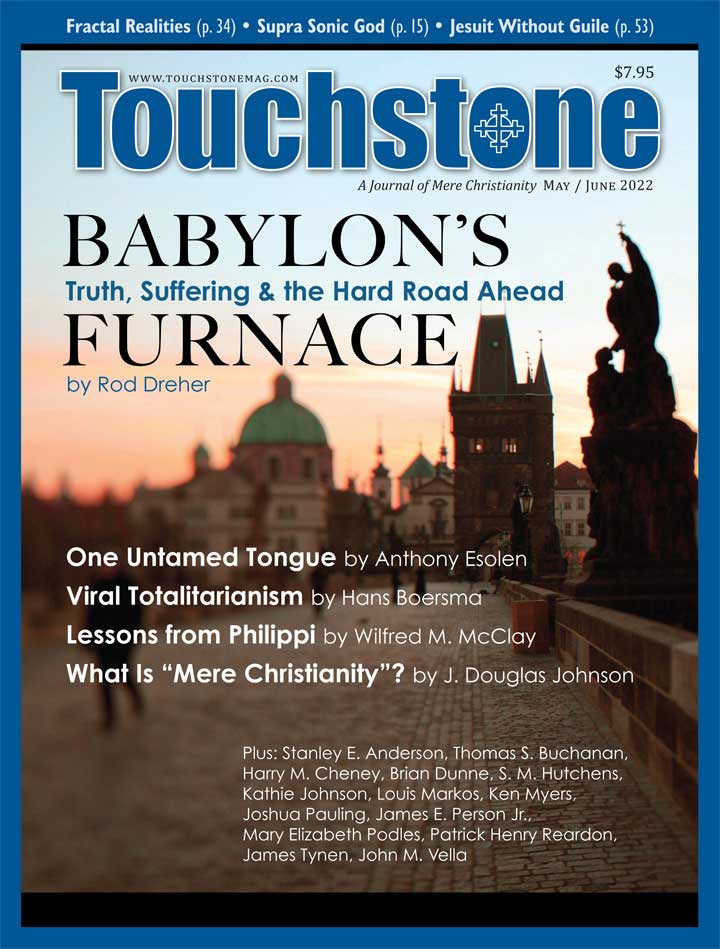

What Is "Mere Christianity"?

Quod Ubique, Semper, et Ab Omnibus

by J. Douglas Johnson

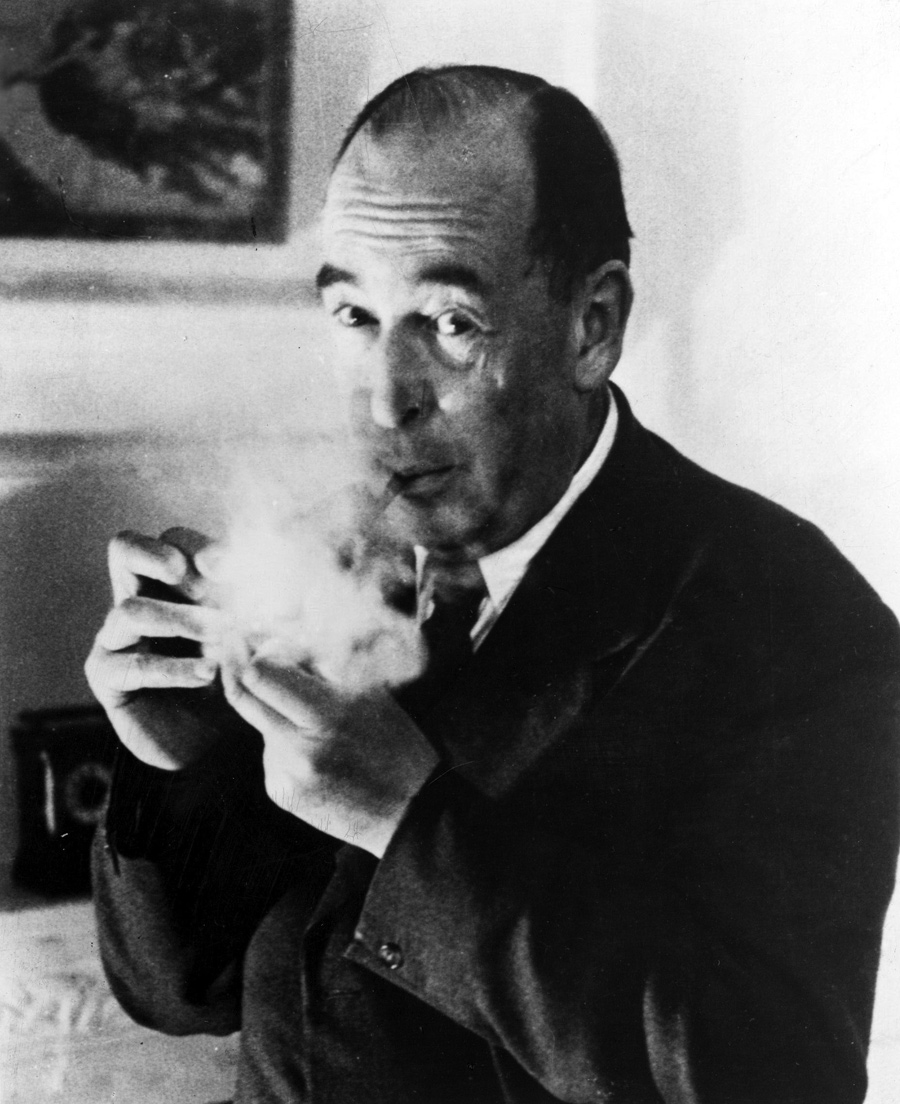

Most readers of this journal know that our subtitle, A Journal of Mere Christianity, refers to C. S. Lewis's book of the same name. It is worthwhile, from time to time, to review what Lewis meant by this phrase. The answer is not as straightforward as it might seem.

The most common misinterpretation of what Lewis meant goes something like this: "Mere Christianity is what everyone who calls himself Christian today can agree upon without regard to those doctrines unique to Roman Catholicism, Methodism, or whatever." This is a common misinterpretation because, while it comes quite close to what Lewis said, it is nearly the opposite of what he meant. Indeed, in the preface to Mere Christianity, he explains the lengths to which he went to avoid saying anything exclusively tied to or offensive to particular denominations:

The danger clearly was that I should put forward as common Christianity anything that was peculiar to the Church of England or (worse still) to myself. I tried to guard against this by sending the original script of what is now Book II to four clergymen (Anglican, Methodist, Presbyterian, Roman Catholic) and asking for their criticism. The Methodist thought I had not said enough about Faith, and the Roman Catholic thought I had gone rather too far about the comparative unimportance of theories in explanation of the Atonement. Otherwise all five of us were

agreed.

Later in the preface, Lewis imagines "mere" Christianity as

a hall out of which doors open into several rooms [each representing a separate Christian denomination]. If I can bring anyone into that hall I shall have done what I attempted. But it is in the rooms, not in the hall, that there are fires and chairs and meals. The hall is a place to wait in, a place from which to try the various doors, not a place to live in. For that purpose the worst of the rooms (whichever that may be) is, I think, preferable.

Once again, mere Christianity as a sort of common ground of agreement by all who call themselves Christians sounds like what Lewis may have had in mind, doesn't it? And so what prevents the church that hangs a rainbow flag over its entryway from claiming that it is simply another door along Lewis's hallway of mere Christianity? By what criteria might Missouri-Synod Lutherans and Eastern Orthodox Christians have rooms off that hallway, but not, say, the United Church of Christ?

If we imagine mere Christianity as an island of common ground upon which all Christians today can agree, then all power lies in the hands of the innovator, who only needs to disagree and, voilà! the island of common ground shrinks as it sinks a little further into the surrounding waters of modernity. All readers of this journal have had the experience of hearing some dullard brush aside even the most fundamental teaching of the Church with the stock phrase, "But not all Christians believe that." Well, Christianity isn't a list of beliefs upon which everyone who calls himself a Christian agrees.

The Deceit of Novelty

Then what, in Lewis's formulation, protects the Church from such perpetual erosion? The answer appears on the second page of his preface: "Ever since I became a Christian I [have meant] to explain and defend the belief that has been common to nearly all Christians at all times."

It is Lewis's invocation of "at all times" that shores up the ground on which we stand. It is not tradition that needs to keep pace with modern times, but rather modern men who must give up their innovations if they really wish to sit at the same table with the saints and apostles: with the early martyrs Ignatius of Antioch and Polycarp of Smyrna, with the sixth-century parishioners of Hagia Sophia, with the missionaries of every age who brought Christianity to millions around the world from Iceland to Argentina, and with countless others, mere Christians all.

"If some novel contagions try to infect the church," wrote the fifth-century Gallic monk, St. Vincent of Lerins, "then [I] will take care to cleave to antiquity, which cannot now be led astray by any deceit of novelty." St. Vincent formulated what has since become known as the Vincentian canon: Quod Ubique, Semper, et Ab Omnibus (that which has been believed everywhere, always, and by all).

Twelve hundred years later, the seventeenth-century Protestant clergyman Richard Baxter coined the term "mere Christianity," which Lewis adopted. "I am not writing to expound something I could call 'my religion,'" Lewis said, "but to expound 'mere Christianity' which is what it is and what it was long before I was born and whether I like it or not."

The Arrogance of Time

Most readers of this journal would happily choose to set aside our modern innovations in order to take our seats at the table of mere Christians, but the choice isn't as simple as it seems. Consider that to even speak of "modern times"—in fact, even to identify ourselves in terms of our time at all—is one of the innovations. In the introduction to his book The Theological Origins of Modernity, Michael Allen Gillespie asks,"Do we even understand what it means to be modern? The premise of this book is that we do not." Gillespie continues:

[T]o think of oneself as modern is to define one's being in terms of time. This is remarkable. In previous ages and in other places, people have defined themselves in terms of their land or place, their race or ethnic group, their traditions or their gods, but not explicitly in terms of time. . . . To be modern means to be "new," an unprecedented event in the flow of time. . . . To understand oneself as new is to understand oneself as self-originating. . . . To be modern is to be self-liberating and self-making . . . something Promethean. But what can possibly justify such an astonishing, such a hubristic claim?

Modern men pride themselves on having been born in this era of anesthetics, indoor plumbing, and air conditioning, and not in the morally backward times of Viking raids, the Black Death, and "religious superstition." As the Polish philosopher and politician Ryszard Legutko points out, this arrogance of time has corrupted our use of language:

The favorite expressions of condemnation always point to the old: "superstition," "medieval," "backward," and "anachronistic"; the favorite adulatory term is, of course, "modern." It goes without saying that everything—in both communism and liberal democracy—should be modern: thinking, family, school, literature and philosophy. If a thing, a quality, an attitude, an idea is not modern, it should be modernized or end up in the dustbin of history (an unforgettable expression having as much relevance for the communist ideology as for the liberal-democratic).

It is not the goal of Touchstone, nor of mere Christianity, to return to an earlier time. Lewis was explicit about this. (Indeed, how can we attempt to break free from the innovation of defining ourselves in terms of our time by setting our sights on another time?) And yet, if we aspire to Quod Ubique, Semper, et Ab Omnibus, then it is the mission of this journal to identify and disentangle ourselves from the innovations that prevent us from taking our seats at the table of mere Christians, and to help others do the same.

This is no easy job, as no one man can free himself from all the innovations that entangle us today. But we would do well to remember that when we talk of "our time" or use phrases like "modern medicine" we are participating in something that man made up around about yesterday along the scale of human history.

This is not a job that anyone can do on his own. We occasionally receive a thoughtful and well-written article that seems to jump all the editorial hurdlesonly to be declined in the end because one or two editors spotted an innovation that the others missed. Protecting ourselves from disseminating such errors requires an editorial board with Christian historians, philosophers, and biblical scholars on it, along with mere Christian critics of literature, art, and music.

Where the Good Way Is

In 1945, Lewis reminded youth leaders and junior clergy at the Carmarthen Conference in Wales that their

business is to present that which is timeless (the same yesterday, today and forever—Heb. 13:8) in the particular language of our own age. The bad preacher does exactly the opposite: he takes the ideas of our own age and tricks them out in the traditional language of Christianity.

It is not just bad preaching that Touchstone battles, but two of the great progressive presumptions of our age: (1) that we have the power to veto the ancient wisdom handed down to us; and (2) ironically, that we have triumphed, scientifically and therefore (somehow) morally, over those who came before us. We heed the words of the Lord to the Prophet Jeremiah:

Stand by the roads, and look,

and ask for the ancient paths,

where the good way is;

and walk in it, and find rest for your souls.

But they said, "We will not walk in it." (Jer. 6:16)

J. Douglas Johnson is the executive editor of Touchstone and the executive director of the Fellowship of St. James.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor