The Church Unmasked

Aaron Ames on the Church's Failure in the Pandemic as Symptomatic

When once we are finally unmasked, what will be revealed about us? The year 2020 was almost certainly the first time in history that the global Christian Church collectively shut its doors for any significant length of time. While the Covid pandemic has sparked an abundance of discussion about what it means to love one's neighbor, there has been little discussion about what it means to love God.

In a.d. 251, St. Dionysius, bishop of Alexandria, wrote that the devastating plague of his time, which "nearly killed" off the Roman Empire, "so far from being a time of distress, [was] a time of unimaginable joy."

This is the spirit in which the early Christians weathered two devastating pandemics, in the second and third centuries, that resulted in massive depopulation. As historian Edward Watts has detailed, "abandoned farms and depopulated towns dotted the countryside from Egypt to Germany." Yet beyond the nasty symptoms, Watts noted, "most of all . . . the disease spread fear." Hans Zinsser elaborates in Rats, Lice, and History:

[T]he forward march of Roman power and world organization was interrupted by the only force against which political genius and military valor were utterly helpless—epidemic disease . . . and when it came . . . all other things gave way, and men crouched in terror, abandoning all their quarrels, undertakings and ambitions.

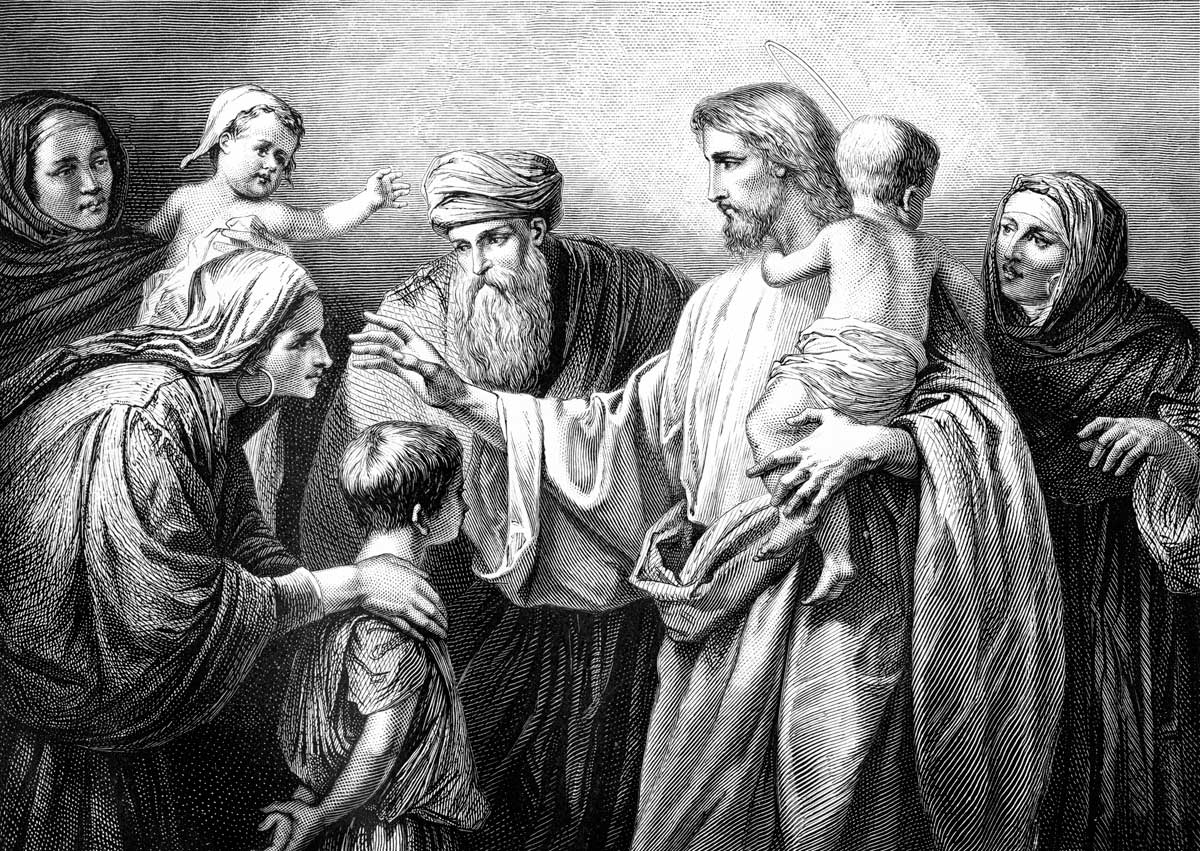

Christians, however, rejected fear of death for love of God, neighbor, and enemy, and became the caretakers of the cities. According to Dionysius, while "the heathen . . . pushed the sufferers away and fled from their dearest, throwing them into the roads before they were dead," Christians "showed unbounded love and loyalty, never sparing themselves and thinking only of one another. Heedless of danger, they took charge of the sick, attending to their every need and ministering to them in Christ, and with them departed this life serenely happy."

What resulted was a massive surge of Christianity from the fringes of society to the center of society in a matter of a century. Indeed, this Christian vision was so formidable during these two pandemics that sociologist of religion Rodney Stark argues that, "had classical society not been disrupted and demoralized by these catastrophes, Christianity might never have become so dominant a faith."

The Right Question

In contrast to the early Church's embrace of the pandemic of its day, our contemporary Church has fled from the Covid pandemic, shutting its doors for fear of death and devastation. Whereas Jesus reached out and touched the leper, we have declared everyone a leper, and invited no touching. And when we did reopen our church doors, it was not without the aesthetic decorations of a multitude of otherwise out-of-place liturgies. With the sight of churchgoers, separated by a minimum of six feet, dotting the room in small, isolated pods, and standing with mouths and noses fully covered to sing "Thine Be the Glory" in muffled tones, one would be hard-pressed to believe that their element of ultimate concern was the crucified and risen Lord.

If our spiritual nourishment as Christians is predicated on regularly receiving the grace of God through communal fellowship, participating in the sacraments, and hearing the Word, then it is objectively true that our teachers and administrators have voluntarily overseen the single greatest withholding of spiritual nourishment in the history of Christianity. But placing blame squarely on church leaders would be unfair, considering how many churchgoers themselves welcomed the strictures, even sometimes demanded them. While some might blame their state governments for the mandated lockdowns, this, too, would be unfair, since so few churches dared even to protest, much less resist, such mandates.

What, after all, informs the Church's vision of the good life? For all the talk about the possible ineffectiveness of masks, their potentially harmful side effects, and their use as a tool of oppression, it is troubling how rarely the Christian subculture has entertained the more important spiritual question.

We have been so schooled by our culture that the question we most often ask is, "What's this for?"—a mundane question of utility. Instead, we should be asking, "Who are we becoming?"—which is the higher question of virtue and religion. If it is true that "man does not live by bread alone," then our Christian generation has fatally misunderstood the hierarchy of health.

Christ Masked & Distanced

Our vision of the good life has been repeatedly and habitually informed by the world. And our churches are a testament to this vision. Worship services are often indistinguishable from rock concerts. Our communications borrow entirely from the propagandist techniques of mass advertising. But if our corporate worship spaces are intended to be vivid representations of the coming of the New Heavens and the New Earth, then why do they so much resemble our contemporary culture?

And while we long since should have been sounding the alarm bells over our dangerous assimilation of that culture, we are all, after this past year, particularly without excuse. For nothing has so plainly revealed our lack of spiritual health than the image of the Church during the past year. Writing in The Aquila Report in May 2020 on the question of Christians and masking, Rev. Jim Fitzgerald warned of the spiritual impact:

Wearing masks en masse . . . will ultimately diminish us as persons. It will dramatically change our behavior towards others. . . . Our neighbors will be perceived as something to protect ourselves from, rather than someone with whom I commune. . . . At the very least, the obvious awkwardness would greatly distract us from the seriousness, solemnity, and joy that should accompany participating in the sacraments and other elements of worship.

And while it is tempting to ask whether Jesus, if present today, would be walking around wearing a mask and abiding by social distancing guidelines, such a debate would only distract from the reality that Jesus did, in fact, spend the last year masked and distanced. If it is true, as Catholic theology contends, that the Church represents the very "Face of Christ" that "shines most intensely in the saints and witnesses of the faith," then we have spent the past year masking the majority of Christ's recognizable features. If the curious unbeliever had spent last year on a mission to spot Christ, he would have had a difficult time discovering him in the usual places.

Jesus himself stated that the world would find him in the midst of the communal, sacrificial love shared between his disciples (John 13:34–35). But what happens when these so-called disciples no longer share anything communal or sacrificial? If Jesus' face is vividly perceived in the humble work of those who, likewise, came "not to be served but to serve" (Matt. 20:28), where was Christ to be found when his servants took a year off?

Immersed in Fear Instead of Hope

But perhaps the most obvious failure is succinctly summarized in the words of Msgr. Charles Pope: "the widespread, gripping fear in the face of this virus is unprecedented in my lifetime. . . . Its worldwide scope tells me that it is demonic in origin, and thus the Church must speak more vigorously to exorcize the demons of fear. Instead we have remained strangely quiet." Yes, the Church has remained strangely quiet in its year-long endorsement of nurturing a widespread culture of fear, when our primary calling is to "fear the Lord."

This is possibly the first time in history that the global Church has strayed so far from the vision of the eschaton, wherein we are promised that there "will be no more death or mourning or crying or pain" (Rev. 21:4). We exchanged the long-term vision of the New Heavens and the New Earth for the short-term vision of the here and now. Worse, we could see nothing but the pandemic. It ruled our thoughts, actions, and corporate life (or lack thereof). Instead of clinging to the spiritual hope in the "evidence of things unseen," we clung to the material fear of death. But where, O death, is thy sting!

C. S. Lewis's oft-cited statement in Mere Christianity might be more apt now than ever: "If you read history you will find that the Christians who did most for the present world were precisely those who thought most of the next. It is since Christians have largely ceased to think of the other world that they have become so ineffective in this."

With all the admonitions to "trust the experts" and "trust the science," where was the exhortation to "trust the Lord"? Our understanding of the present must always be informed by our hope of the future, and we will continue to veil the Face of Christ until we restore our long-term vision to its proper eschatological place: look to heaven to better see earth.

The Christian hope is that one day, in that final beatific vision, we will all see God "face to face" (1 Cor. 13:12). Until then, the physical reminder of this hope is the unique and wonderful face of another human being, whose image testifies to the very image of God, which is seen most clearly through the blessed smile of the human face. In a 2015 essay titled "Becoming Human in the Face of God," Hans Boersma comments that, through the sight of each other's faces, "it is possible to see God's beauty in ourselves as in a mirror."

Citing the work of Gregory of Nyssa, Boersma also remarks that just as we can see glimpses of the face of God in a person's physical face, we can even more vibrantly see the vision of God in the cultivated soul of another person. This is how the saints of Christian history bequeath to us such a powerful portrait of Christ. Boersma concludes his essay with a startling critique:

As human beings . . . we attain our identity (and so become fully human) only to the degree that we explicitly aim for the supernatural goal of the beatific vision, which God places before us as our true fulfillment. The reductionism inherent in the modern abandonment of the beatific vision is, therefore, much more serious than may at first appear. It means a turning away from the infinite God . . . in favour of a reorientation of the human gaze toward this-worldly goods. The loss of the beatific vision as the purpose of human existence leads to a "spirituality" in which nothing any longer exceeds the ebb and flow of this-worldly human desires.

A Straying Church Called Back

The mask is finally and fully off, and we have discovered, as George MacDonald said, that "the supremely terrible revelation is that of a man to himself." Indeed, when we hold the mirror up to gaze upon the unmasked face of our contemporary Church, we find a terribly mutated thing that looks nothing like what we thought. MacDonald reflects on such an appalling self-revelation: "Think what it must be for a man counting himself religious, orthodox, exemplary, to perceive suddenly that there was no religion in him. . . . What a discovery—that he was simply a hypocrite—one who loved to appear, and was not!" And such was the discovery, not of one man, but of the entire Church.

Yet, despite all our failures and foibles, we can still declare with hopeful affirmation, "Thanks be to God!" For perhaps God's grace is never more generous than when he reveals to us the error of our ways. In light of the Church's abandonment of its most sacred duties, the Lord could not have given us a more obvious invitation to repentance. We must, then, welcome the judgment of the Lord, which Peter Kreeft reminds us "is necessary, both to live well on earth and to enter Heaven."

Though it is painful to hear the Lord's condemnation that we have "exchanged our glorious God for worthless idols" (Jer. 2:11), we are promised in the eternal providence of God that such a judgment is the very means by which God will bring us "back from captivity" (Jer. 29:14). The Church may have strayed from her calling, but rest assured that our Lord has not strayed from his Church. After all, we are promised that the final unveiling of the Church will be as a "bride beautifully adorned" (Rev. 21:2). So while we may not have looked much like Christ this last year, by the grace of God, we will.

Aaron Ames has published articles for The Federalist, The Imaginative Conservative, and American Thinker, among others. He teaches rhetoric and logic at a classical school in Kentucky.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor