The Death of the Lord

on Mortality as a Framework for Life & Love

On November 21, 1922, a new play was introduced on a stage in Prague. It was one of two plays that appeared that year by a young writer named Karel Capek. The title of the production, in the original Czech, was Věc Makropulos, literally "The Makropulos Case."

It is appropriate that Capek's theatrical work was soon converted to an opera, because it does, in fact, tell the story of an opera singer; her name is Amelia.

According to the plot, Amelia inherits an elixir that, when she drinks it, maintains her youth for another three hundred years, at the end of which period she can simply drink it again, and then again, every three hundred years, for as long as she wants. In principle, that is to say, Amelia can go on living forever.

Not Boredom, but Another Burden

It is hardly surprising that this play, during the 99 years since it first appeared,has been the subject of serious philosophical reflection and the focus of critical comment, especially in the realm of psychology.

For instance, in 1973, philosopher Bernard Williams devoted a whole chapter to the play in a book of essays entitled Problems of the Self. Williams considered, for example, whether or not a human being might become terribly bored if he lived an extra three hundred years, to say nothing of living forever.

If we consider the subject of immortality solely from the perspective of the human mind and its curiosities, I don't think some of us would ever become bored. I confess, for my part, that I would start my life's extension by spending the next century or so catching up on the books I failed to read, the music I did not listen to, the art works I did not see, and the places I neglected to visit, during my merely octogenarian lifetime.

For instance, I fancy devoting the next hundred years to the study of Sumerian and Coptic; then I would apply my mind, for two or three lifetimes, to the pursuit of the Talmud. Perhaps then, if the mood took hold, I would learn to read ancient Chinese literature in the original.

Moreover, if I were to live another three hundred years after that, there would be three hundred extra years of history to study, and I would want to spend a few centuries, at least in the evenings, watching reruns of my favorite movies.

In short, I do not think boredom would be a problem.

But a problem there certainly would be! If I alone received immortality, then all those I know and love would die, and they would leave me here alone with my memories and remorse. My heart would be broken a thousand times; the longer I lived, the worse it would be. Existence would become utterly miserable, a burden truly unbearable, and I would pray, with that repeatedly broken heart, to be delivered from it. Roger Scruton was wise to place the remembrance of death's certainty among his "uses of pessimism."

Bad, but Manageable

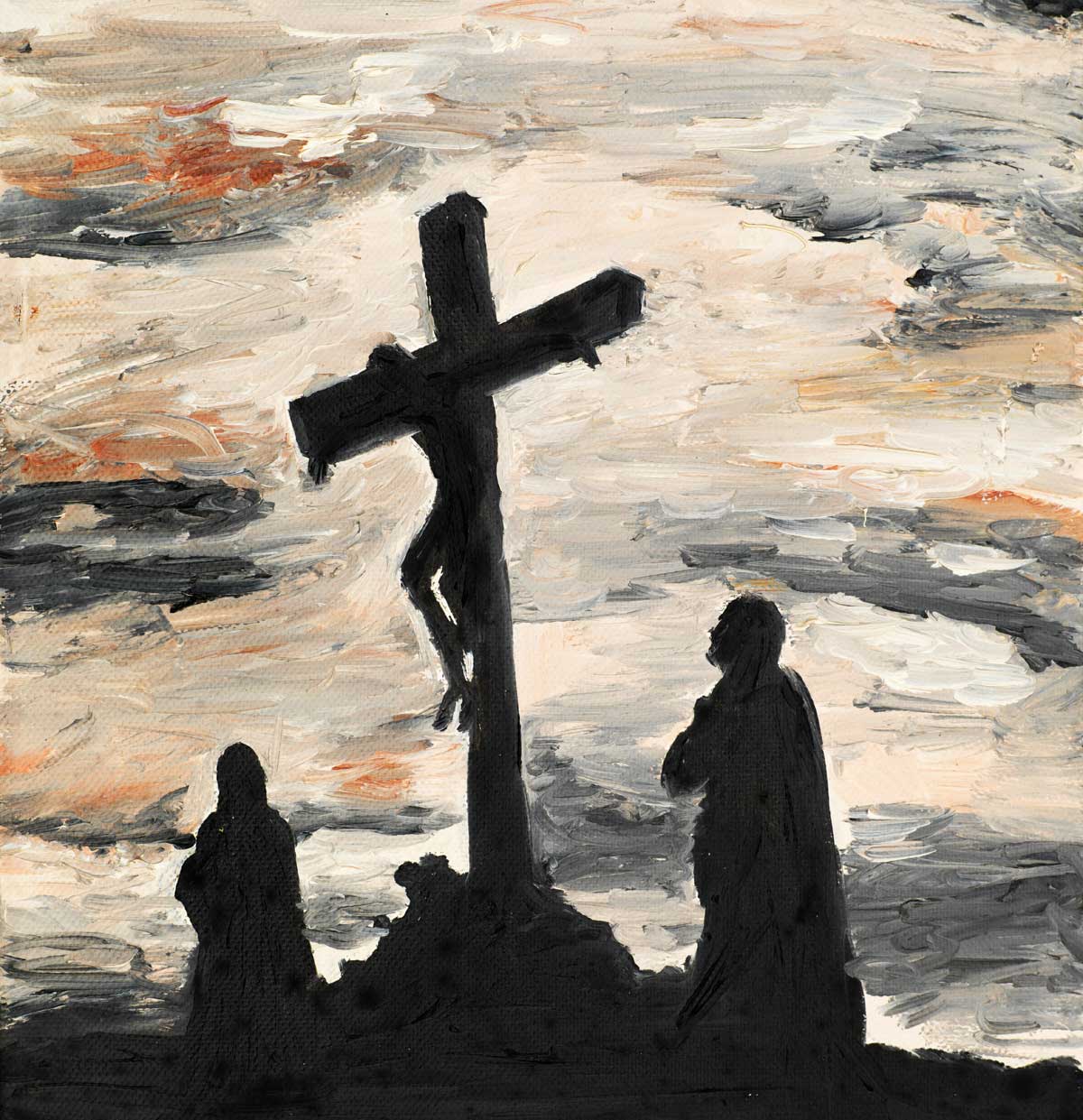

What is a Christian to say of this? Can death be a good thing? As the medieval schoolman used to say, opus est distinctionis—we need to make a distinction. Of course, the Christian affirms that death is bad; it is the enemy. Christ, by rising from the dead, defeats death. His Resurrection affirms that death will not have the final word in human history. It is among the final promises of the Bible that "death will be no more." So death is certainly a bad thing.

But when we affirm that death is a bad thing, we are not considering the subject solely from the perspective of our individual deaths. It is important to place death in a far larger context; the full significance of the evil of death must consider the death of everybody. If everybody dies, this is something we human beings can deal with. Hard as it is, death becomes manageable. The thought of it need not drive us crazy.

Understood in this perspective, the death of a single human being is not necessarily a tragedy. Death can be precious, not only in the sight of the Lord, but also in the sight of men.

A Framework for Life

One of the blessings of death is that it provides a structural context in which we human beings do our work. That is to say, death supplies a framework for life, an enabling limitation that braces us to life.

Our mortality, even as the inheritance of Adam's fall, is and will always be part of the structure of human existence. It is important that we die. And Christ our Lord has given us ample reason not to fear it.

When God sent us his Son to be one of us, this Son accepted death as part of the package. Since Jesus knew no sin, he was not obliged to share in the inheritance of Adam; he did not have to die.

Yet, he consented to die, because he willed completely to become one of us. So his existence, too, was framed within a structure marked by death. His life assumed the limiting framework of man's mortality.

Indeed, Jesus speaks of this very thing when he tells the disciples, "You have the poor with you always, but you do not always have me." His love for them, he declares, and their love for him, is very different from the universal moral principle that dictates our commanded care for the poor. The latter responsibility will always be there.

What will not always be there is the friend whom we love. Jesus reminds his friends of his, and their own, mortality. We are given but a short time to learn just one thing: how to love. God blesses us with only one life, and one task.

Written across the breast, then, of everyone we know, inscribed on the face of everyone we meet, scrawled on the soul of every mortal being who walks this earth, we do well to read the declaration of Jesus: "A little while I am with you, and you will see me no more. You do not always have me."

Patrick Henry Reardon is pastor emeritus of All Saints Antiochian Orthodox Church in Chicago, Illinois, and the author of numerous books, including, most recently, Out of Step with God: Orthodox Christian Reflections on the Book of Numbers (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2019).

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on Christianity from the online archives

more from the online archives

27.3—May/June 2014

Religious Freedom & Why It Matters

Working in the Spirit of John Leland by Robert P. George

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor