The Gift of Samuel

Children, Marital Intimacy & Divine Desire

Hedonists everywhere should be concerned; after all, lust is what it has always been. Even when it is attended by pleasure, lust remains ungratified and ungratifying. This will surprise no one, but it does seem to bother some. Otherwise, there would not be such a rush to exalt lust as love, or to confuse their rewards.

Consider that, in 2017, New York State mandated that insurers provide coverage for infertility treatments to anyone, regardless of the person's marital status or sexual practices. The state already required insurers to cover infertility treatments for women who sought pregnancy naturally; the new directive extended that coverage to unmarried women and homosexuals. As the administration in New York allegedly strove to protect "reproductive choices," it is plain that it was most pleased to have created a "choice" where none existed before.

It is some homosexuals, then, who seem so confused and unhappy about the evident, persistent biology of their bodies that they now insist upon receiving the reward of perceived intimacy—i.e., children—even when nature forbids it. But lust and love are not the same, and the rewards of the one cannot be conferred upon the other, whether this is acknowledged or not. This was, of course, all settled ages ago: Scripture and the natural order speak clearly enough, but that hasn't stopped activists and bureaucrats from mounting an argument against biology, mainly because men and women continue to argue with God.

If homosexuals have any argument at all, it is essentially and inevitably one of sentiment. But whether the sentiment that some homosexuals call love is endearing and enduring is not a relevant question; rather, it is appropriate to ask whether the sentiments they profess and act upon can ever resonate in the way that intimacy between a man and a woman naturally and normally does, that is, in the conception of a child. The obvious answer to that question is no; but then again, intimacy is evidently not what it used to be, and so we find New York (with other states likely to follow) distributing rewards for fornication.

Of course, unmarried heterosexual couples also frequently employ the same argument of sentiment—and that without the biological inconveniences of the homosexual. In the Western world, marriages occur less frequently than they used to, while cohabitation and pornography use are on the rise. In other words, Americans are not sexually inactive, only deviant. American heterosexuals naturally conceive children, but they increasingly do so outside of marriage.

True Intimacy Is Continuous

This leads us to state the obvious: that the marriage vow is not necessary for the natural conception of a child. This is not to say, however, that the natural and ordinary manner of conception always brings about a happy child; in fact, it is apparent that it does not. Although increasing numbers of children are born to unmarried heterosexuals and are raised by such couples with increasing regularity, the unhappy results of this are demonstrated in numerous studies. But the manifest irony is that this too-prevalent sin among heterosexuals has resulted in a world where homosexuality is increasingly accepted as normal.

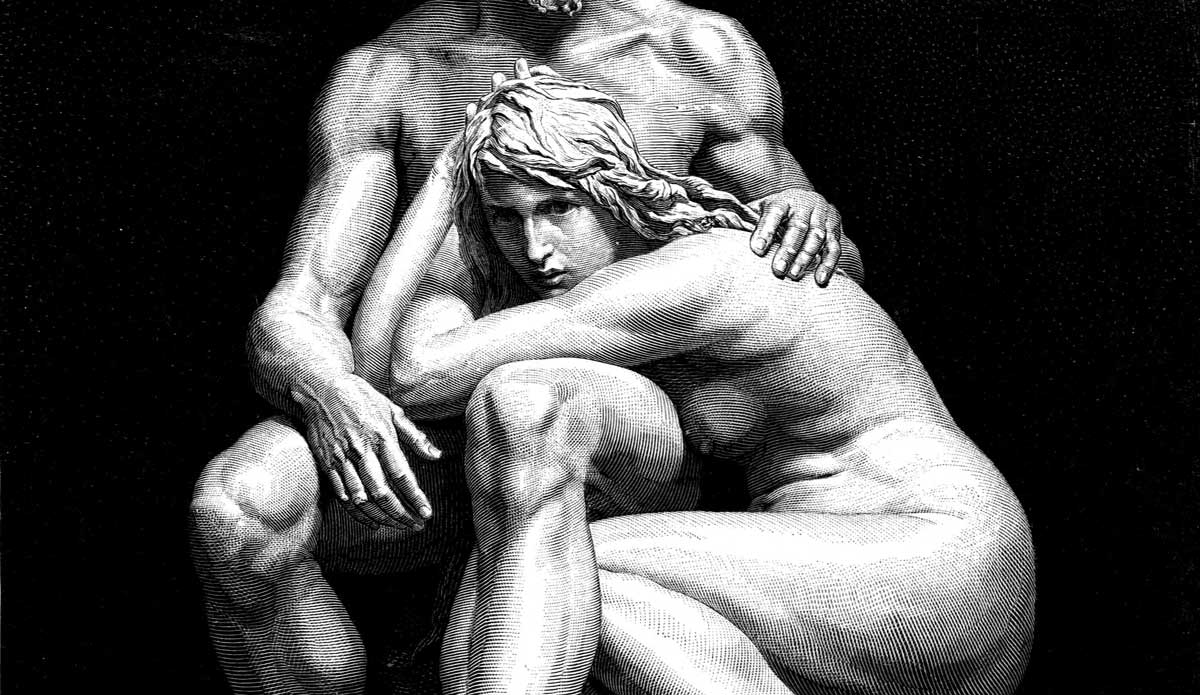

And this brings me to my ultimate concern: that there is something about the continued intimacy between a man and a woman—a husband and his wife—that is germane not merely to what it physically conceives in the moment of conception, but also to what it can subsequently bring about in the nurture of a child into an adult, a child who must then live in the world that he inherits from his biological parents.

Is there a real difference between lust and intimacy, other than the uncertain, halting perceptions of lovers? Indeed, there is, but it is not a distinction of sentiment; rather, it is a distinction of actual potency. Whatever their intensity, passions alone can never produce what it is hoped or pretended they can, for there remains the matter of biology. But we best regard intimacy by an additional measure still: by what it is able to anticipate, embrace, and finish, that is, the nurture of a child that a man and wife conceive and then raise together.

It is true that increasing numbers of unmarried people are having children, but then again, families are not what they used to be. Homosexuals may attempt to raise a child, but it is never one they conceive between themselves. And although heterosexuals may naturally conceive a child, this does not mean they will raise it properly by themselves.

Intimacy, then, is not reducible to the mere affections of a husband and wife, for it is preceded by a vow but then ends in something more. Indeed, a married couple's proper enjoyment of one another ordinarily results in the conception of a child, but it continues in the proper nurture of the child into an adult. Let me say this: the raising of a child minimally depends upon the continued and various kinds of intimacy between a husband and wife. Americans will disagree with one another on policy, but the Christian argument against homosexual "marriage" is not just a cultural quarrel. There is something behind all of this that exceeds even ethical principles and cultural concerns, important as they are. When sexual ethics are reduced to mere temporal questions, their eternal significance is not just undone; more frighteningly, it is forgotten.

Hannah's Barrenness

Let us consider the story that opens the First Book of Samuel. It is the story of three persons: a Levite named Elkanah and his two wives, Hannah and Peninnah. Elkanah and Peninnah are chiefly described by what they do—Elkanah is pious and visits the temple, while Peninnah is busy with the children she has by him. Hannah, however, is described by what she is unable to do: conceive a child. She stands out by reason of her barrenness.

Unsurprisingly, the reader grows increasingly sympathetic toward Hannah. She is obviously hurt by her condition, and even those readers who have not been burdened with a disappointment of her kind feel this in some degree. Hannah weeps and prays for a child, and then weeps some more. Her husband's efforts to cheer her are feeble and unavailing, and Peninnah meanwhile continually provokes Hannah for her barrenness. Here, the first of the story's many ironies becomes evident: Elkanah and Peninnah, first noted for what they can do for themselves, are now also to be noted for what they cannot do—help Hannah in her condition.

It is written that this condition continues "year by year." What is more, we read that it is God who has closed Hannah's womb. And so, all sorts of things might go through the reader's mind—for one, that God is unfair. If we think this, our sentiments, predictably, will begin to assert themselves. After all, Hannah was without a common blessing. There were others who had many children, but she had none. Even those who committed their children to idols and the fire were given them, and then given more; but Hannah had no child.

These were hard years. God's will surely seemed harsh; Hannah had to struggle for a blessing even while she struggled against her own grief and bitterness. And in these struggles, Peninnah was always present as an adversary against Hannah's good desire.

Another irony is this: Hannah's adversary, Peninnah, did not shut Hannah's womb, but only antagonized her for what the Lord had done. Importantly, Hannah could have reacted differently than she did. She could have striven against her adversary directly, but there is no evidence that she did so. Instead, she chose to give herself to prayer, and to come before the Lord with a vow. So she traveled to Shiloh, even in the time of harvest, even while she remained barren of a child. And it is then and there that her story coincides with another.

The Corruption of the Peace Offering

While Hannah's narrative is developed, another has continued in the background, and it now comes to the forefront. Israel is evidently in a period of apostasy: the Jewish people have been betrayed by those they necessarily trusted, their priests. The reader sees this by the description of the manner in which sacrifices are offered. Whereas the Mosaic law required that the people take their offerings to the tabernacle then in Shiloh, where the priests were to divide them in a prescribed manner, we find the priests taking the sacrifices in their entirety for themselves (1 Sam. 2:12–17).

This brings us to something important: although there were several kinds of offerings, there was only one that allowed the person who brought the offering to share in the enjoyment of his sacrifice. This was the peace offering, and it seems to be the offering mentioned here. The peace offering was to be divided into three parts: the fat would be burned to the Lord, a second part given to the priest, and a third part given to him that brought the offering. Rubrics for the other kinds of offerings prescribed that parts be given to the Lord or to the priests, but only the peace offering had an additional provision for the immediate happiness of whomever brought it, for it allowed him to eat of the same offering he gave. In this way, the peace offering aptly signified the possible and intended intimacy between God and man.

But the priests in Shiloh insisted that the entire sacrifice be given for their own satisfaction. Through the account in 1 Samuel, the reader discovers how the priests would steal the offerings from the people, and so the people then not only hated the priest, but also despised the offering that God had prescribed. What had been intended for their enjoyment now effected their anger and their eventual unbelief. In this way, the lust and covetousness of the priests highlight the enmity between God and man, rather than assuaging it. Hannah is disappointed in her barrenness, and the Jewish people are disillusioned by reason of their spiritual emptiness. We sympathize with them all—the themes are uncomfortably common.

This is where the consideration of the peace offering becomes so important. This offering was meant to provide for the mutual and simultaneous gladness of both God and man, and not for one of them only. The one offering that satisfied God also provided for the satisfaction of man. At least as far as this offering was concerned, there was nothing that a man might offer to God that God did not in some measure already order for that man's pleasure. God and man found happiness by the one and same sacrifice.

The wicked priests Hophni and Phinehas did not know the Lord, so they had little regard for what they withheld from men to satisfy their own lusts. They withheld the offering for themselves, but then lost much more. For in keeping the offering for themselves, they withheld God's blessing from those for whom God intended it. And in withholding from men the opportunity to taste of God's goodness, they also withheld from God what he still seeks from men: their resounding praises whenever they recognize, receive, and enjoy what God has given them.

Hannah's Peace Offering

This is where the two narratives merge. We easily comprehend the fact of Hannah's barrenness, but it is more difficult to understand why God, at least for a time, was the one who withheld a child from her. (Hannah, too, must have wondered about the long silence of God, but God had surely wondered at the silence of his people.) For many long years, Hannah waited for a child and none came. She looked for honor—the sort of honor due to all mothers, but found reproach instead. She prayed for a child, but remained barren. But had not the Lord waited for honor much longer than she? Had he not long hoped for Israel's prayers and praise and heard only silence—or the complaints of a people who now abhorred the Lord's offering because of a corrupt priesthood?

By her barrenness, Hannah learned something of what God already knew: that one must give before one can receive. But she also learned that one must first possess the actual ability to give, and not just the desire. And that ability to give is first given to us by God. Hannah had to receive from God before she could give again to him. And God had to give to Hannah before he would receive from her.

So God eventually did give a son to Hannah, and she then gave that son to the Lord. And the Lord employed that son in the service of his people, after which the people did praise their God.

When Hannah was eventually given the child she had so desperately desired, she named him Samuel. She had sought that child in prayer, but then vowed to give that same child for whatever service he could render in the tabernacle in Shiloh. So it finally appears that, in a sense, Hannah vowed a peace offering in her want, even as other men withheld peace offerings from the Lord in their disillusionment, either by refusing to give what they already possessed or by taking what God did not give.

As Samuel grew older, he grew in favor both with the Lord and with men. He eventually restored proper worship in Shiloh, and the Israelites rejoiced in their God again. Hannah received a son, and then gave him to God but also visited him year after year (her portion); and the Lord gained the praises of his people—and all by the one vow that Hannah made to God. God and men enjoyed the same offering. Samuel became the means by which God and men enjoyed one another again. True and consequential intimacy, it seems, had affected all.

God's Design Confirmed

Conception relies upon biology, but must life proceed only in the manner that biology may take it? That happens only among the animals. Intimacy between persons has regard to both the influence and consummation of trust, and not simply its beginning, so that what intimacy conceives in the bedroom it may carry further into the world outside through another person, a child. The mutual happiness of a husband and wife ordinarily leads to the conception and then to the nurture of the same child, even if inadequately so. Sadly, some couples suffer the sorrow of being unable to conceive a child, but all of us who do have children also know that we have not always consistently raised them in the manner we have wished. This is because of a deficiency we find within and between ourselves. It is a problem of our own sins and weaknesses, and of their manifestations in our outward relations with others.

To admit this, however, is not to capitulate to those who approach this same matter on sentimental and subjective grounds. It does not speak to a problem in God's design, but rather confirms his original design and how he has renewed it among believers by the Cross. The Christian gospel is clear: a new birth is first required; but that is not the end; that merely begins an intimacy with God by the Holy Spirit. And this God-granted intimacy is to have its fullest sway.

These distinctions speak louder than sentiment can shout. Some relationships yield nothing at all, because it is not possible for them to do so, but it is also true that some relationships bear better fruit than others. They ordinarily end in something more than the immediate pleasure that accompanied their beginning. In fact, a child extends the immediate pleasure of his parents into the future, even unto the love of God and service to other men.

The Better Peace Offering

Intimacy is not what it used to be, unless it is everything it has always been. And some of us believe and confess that it is just that. After all, sentiment alone did not bring salvation to man, but a kind of intimacy was required for Christ's Incarnation. Intimacy between God and men was then later provided for all who believe the gospel, even by the effects of Jesus' own death and Resurrection. And so, in a sense, -Jesus—God's only begotten Son—was the better peace offering. God had to give his Son for man before he could receive from men praise and honor again. Believers enjoy God's free salvation, and God enjoys man's praise—all by the same sacrifice of Jesus Christ.

Some conservatives have made the debate over sexuality, fertility, and family mainly about recovering the culture, but some of us are certain that the goal is much more transcendent than that. Some unbelievers have always been prepared to say that Jesus was born of fornication (John 8:41), while others have confessed that he is the Christ, the Son of the living God. He cannot have been both, especially given his own power and consequence.

Andy Hearn lives with his wife and four children in South Asia, serving there since 2002. They are members of a Baptist Church in the Boise, Idaho area.

Share this article with non-subscribers:

https://www.touchstonemag.com/archives/article.php?id=34-01-035-f&readcode=10498

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on family from the online archives

more from the online archives

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor