Feature

The End of Liberal Democracy

Constitutionalism Without Christian Humanism

Modern teachers of political thought feel obliged to inform their students (almost invariably citizens of democratic republics) that the ancient political philosophers did not think highly of democracy. Certainly, they did not have the reflexive preference for it that we do.

Indeed, there has been quite a turn in the last couple of centuries. In a speech in Parliament in 1947, Churchill called democracy the worst form of government except for all the rest. In an essay titled "Present Concerns," C. S. Lewis said he was a proponent of democracy because he believed in the fall of man and felt that no man could be trusted with unchecked power. Reinhold Niebuhr wrote in The Children of Light and the Children of Darkness that "Man's capacity for justice makes democracy possible, but man's inclination for injustice makes democracy necessary." And William F. Buckley (himself a product of the Ivy League and one of its greatest debaters) quipped in Rumbles Left and Right that he "would rather be governed by the first two thousand people in the Boston telephone directory than by the two thousand faculty of Harvard University."

Our running assumption for at least the last century has been that democracy is possibly the only appropriate form of government for human beings, even if we understand its imperfections. When we evaluate another nation morally, we tend to look first to see whether the people who live there have the right to vote and the package of freedoms that typically accompanies the franchise, such as free speech, freedom of assembly, freedom of the press, and freedom of religion. So we have embraced not only democracy, but also a series of limitations on governmental power designed to keep the democracy from running roughshod over dissenters and minorities. In so doing, we have chosen the constitutional form of democracy over dreaded mob rule. The ancients would have approved of that much.

The Story of the Turn

I suggest we ask what explains the strong turn toward democracy in the modern world and then analyze the sustainability of the trend long-term. It is a story substantially influenced by the fusion of classical thought and Christian faith. We might begin with the idea of the human being as a creature bearing the image of God. All men share this nature. Cicero spelled out a similar understanding in his brilliant Dream of Scipio, in Book 6 of On the Commonwealth. In this passage, the grandson of a great Roman general has a vision that transports him beyond the earth into the cosmos. There he is able to perceive the common lineage of human beings under God, as manifested by their possession of reason.

In The City of God, Augustine brilliantly analyzed the impact of sin on human equality by noting that the desire to dominate is rooted in our fallen, self-serving, self-elevating nature. Rather than seek real peace with our brothers and sisters, we claim that our own desires represent peace. But real peace requires justice. And justice requires taking account of the dignity and rights of others. That reasoning fits nicely with Aristotle's observation in The Politics that men are poor judges of their own cases.

In all of this, we can see the foundations of constitutional democracy taking shape. Ideally, we give and receive consideration, while putting rules in place to curb our passions and self-interest in light of our capacity for self-deception and for disregarding rights beyond our own.

Democracy depends upon more than acknowledging that man is the kind of creature that may deserve the opportunity to participate in governing. The ability to participate is important as well. Practical components (such as the technology of the printing press) joined spiritual, theoretical, and ideological components in the sixteenth century, as Renaissance and Reformation thinkers emphasized primary texts (including the Bible), the translation of texts into vernacular languages, and the project of universal literacy.

The Bible's prominence in a period of broader access to printed texts served to radically increase the power of growing democratization and constitutionalism. Because the Bible was seen as an authoritative text, a populace capable of reading and understanding it could hold leaders and each other to account without relying upon a clerical hierarchy compromised at times by its sometimes cozy relationship with secular powers. A saying from that period held that a ploughboy with Scripture on his side might have the better of a prelate. Put more bluntly, scriptural Protestantism put constitutionalism on vitamins and substantially elevated the potential of the people to take a larger role in governing.

Having offered this account of how democracy overcame its bad reputation and helped lead us into this world of greater equality and self-governance (with the help of Christian and classical insights), what is there to say about democracy's prospects? Shouldn't the future be bright for democracy as we become healthier and wealthier?

The good reputation of democracy in our time doesn't mean that concerns don't linger. Neither does democracy mean that other threats have all been vanquished. Consider Aristotle's reduction of constitutions down to their essences in his Politics. At bottom, Aristotle wrote, constitutions manifest themselves in two fundamental forms: the rule of the rich (call it oligarchy) and the rule of the poor (often known as democracy). Aristotle preferred not to confuse the issue with the formal labels of oligarchy and democracy because his real point was that it was the power that mattered. In the case of the rule of the rich, financial power determined the shape of society. In the case of the rule of the poor, sheer numbers would establish dominance. If neither sounds good, then that is part of the point.

Are we really safe from these challenges that seemed so obvious to Aristotle? We need a government based on more than power, even if a positivistic political science would suggest that it is the only kind on offer.

Borrowing from Cicero

The United States Constitution borrowed a page from Cicero (and others in the classical tradition) in attempting to counter the primal constitutions of wealth and power by setting the various forces against one another. Thus, we have the presidency standing in for monarchy (the rule of the one), the senate representing aristocracy (the rule of the few, hopefully the excellent few), and the house channeling the desires of the democratic will of the people (the rule of the many). By providing a place for these different instantiations of political leadership in a single government, our constitution sought to balance competing interests and models in a new, more enduring and stable composite.

Further balancing occurred by putting in place an electoral college, by having senators elected indirectly through state legislatures, by dividing power between states and the federal government, and by never having the whole of the government up for election at a single time. The senate, for example, is never more than one-third exposed to the electorate. From a structural point of view, the U.S. Constitution is brilliant.

And for the most part, it has worked. Cicero has proved prescient through the labors of our Founding Fathers (and yes, I mean the ones from 1776 and not 1619, as the New York Times would have it). The U.S. Constitution is the oldest and longest-running national governing document in the world today. While it is true that the issue of slavery (which was agonized over for nearly a century before it became the occasion for war) almost brought an end to the republic as it had existed upon the ratification of the Constitution, the nation did survive and has proved durable to the present day.

The attempt to deal with the problem of excessive passion and self-interest through the use of the constitutional devices I've described here represents something like an attempt at enforced virtue. In other words, we have made it hard to misbehave. Our constitution (when observed fairly fully) militates quite strongly against democracy's evil twin, which is mob rule, as well as against oligarchy.

Nevertheless, let me, without rehearsing all the relevant developments, simply say that many of those structural limitations have now been overcome, through either amendment, expansive court decisions, or shrewd use of the powers to tax and spend. As a result, a constitution designed to embody Cicero's wisdom for harmonizing diverse interests and avoiding the excesses of the various classical forms of government has been substantially transformed into something much closer to an ordinary majority-rule democracy. When one notes the calls for the termination of the electoral college, the politicization of the Supreme Court, and the discrediting of federalism due to the South's intransigence with regard to both slavery and civil rights, it becomes clear that we are reverting to the mean as our Ciceronian (and even Calvinistic, as I've written elsewhere) constitutional democracy becomes more typical.

In so saying, I don't mean to romanticize American history to this point, but rather to say that the exceptional features of American democracy, which were designed to curb the ambitions of those looking to fuel and channel the passions of the various factions, are slowly being erased and may not long endure.

Plato, Lewis & the Soul of Man

Of course, the progressive failure of the American structural answer to the perceived instability of democracy and some of the other forms of government is far from dispositive when it comes to answering questions about the fate of the American regime. Structure is a safety valve, a protective device, but there are other issues to consider. Machiavelli suggested that the nature of the persons in a political community would determine much about the type of government they could have. It is reasonable to think that an enduring democratic republic requires some virtue on the part of its citizens.

In his Republic, Plato offered a diagram of the soul that would explain how a human being should live. Within each person resides the head (the reason), the chest (the will), and the stomach (the appetite). In a properly ordered person, the reason will rule the body through the assistance of the will. But for any of us who has ever made a bad choice, it should be evident that the human being can be turned upside down, i.e., that the appetite can rule the body through the assistance of a will determined to fulfill lustful desire. To be rightly ordered is to be philosophic and to see beyond the constantly changing circumstances of the now to what is enduring, good, and real. Among Plato's great concerns were that poets would seduce the young with false ideas about the gods and the nature of the good and that sophists would misuse philosophy for mercenary purposes simply to win arguments without regard for truth. There is a sense in which this is a strikingly modern picture.

C. S. Lewis used Plato's model of the soul as a jumping off point for his argument in The Abolition of Man. But where Plato emphasized the head (the reason), Lewis focused on the chest (the will). He expanded upon Plato's conception of the chest, seeing that part of a man's soul as the repository of his more noble and honorable sentiments. For that reason, Lewis abhorred the modern tendencies to embrace a kind of positivism and to eliminate any sense of extra-psychological reality to be attached to moral and aesthetic judgments. Rather than lifting man to some new, higher level, these tendencies would, Lewis thought, lower human beings into becoming men without chests, trousered apes, and/or urban blockheads. Separating men from what he called "the Tao" would leave them worse off rather than better.

And, of course, to remove one source of meaning raises the question of what will fill the void. According to Lewis, the answer is whatever social elites—he calls them "the conditioners"—want.

Together, Plato and Lewis decry the effort to corrupt the human soul by reducing honor to fool's gold and philosophy to a weapon for the unscrupulous. As we entertain a question about the prospects for democracy in America, we need to ask ourselves whether there are adequate integrative forces to counter the disintegrative ones.

A Painting & Its (Dwindling?) Resonance

With liberalism, we live under a procedural republic. That means we agree to a set of reasonable rules within which our democracy functions. There are some pretty strong rights. The administration of justice is supposed to be transparent and neutral. We have enough faith in our processes to live with the outcomes they produce. But increasingly, this liberalism has come to mean that we do not embrace any overarching form of the good or, if we do, hold it only loosely (as our now-dead philosopher king John Rawls would have it).

Within this frame, we have seen the United States go from being a country about which a Supreme Court justice could confidently declare, "this is a Christian nation" (Church of Holy Trinity v. United States, 1892), to one in which such a statement effectively operates as a bit of an embarrassment. For some time now, we have been debating the question of whether liberal democracy of this evolving type finds adequate foundations within itself to sustain the regime it proposes.

The classic illustration of the cut-flower civilization fits nicely within the inquiry. Have we arrived at the point where our liberal democracy has become a cut flower, disconnected from its sources of nourishment? Was the Christian soil in some way related to the quality of the blooms? Richard Rorty declared himself a happy free-rider on the Western crop of rights and freedoms that theists helped cultivate. Can you free ride forever?

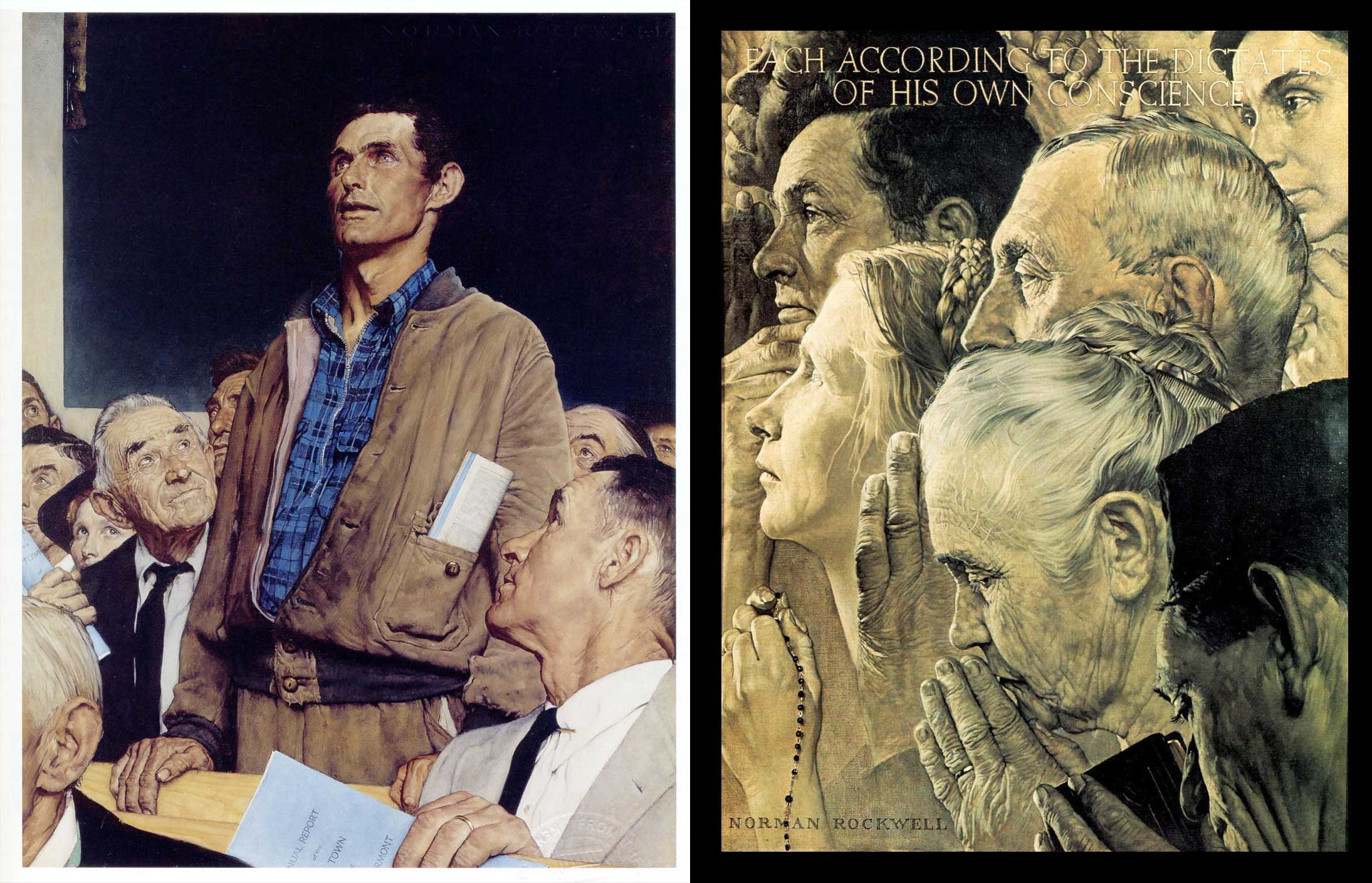

Consider a cultural artifact: Norman Rockwell's painting Freedom of Speech, from his beloved series The Four Freedoms (the others are Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear). I find the image arresting and refer back to it time and again when speaking to audiences or leading discussions with students. The painting portrays a man who appears to be some kind of blue-collar worker rising to speak at a town meeting. In his flannel shirt, khakis, and leather jacket, he looks as though he has come directly from the factory, or at least hasn't changed clothes. Other men at the meeting look like professionals, in suits and ties. Yet all listen attentively, both men and women, a few even craning their necks to see the speaker's face.

There is something striking about his face. When you look long enough, you see it. He is an idealized Abraham Lincoln—at least that's what I see—Abraham Lincoln if he were more handsome than he really was. The speaker appears to be on the cusp of saying something about a civic matter. The other citizens are intent and focused. The whole scene radiates civility, integrity, and seriousness about politics.

I don't know if Rockwell was a Christian (certainly he lived his life in a culture suffused with the faith), but when I look at his work, I see someone who intuitively grasped the human being as someone made in the image of God. It shines through in his work. The civic moment captured in Freedom of Speech is a nearly perfect picture of politics for image bearers.

Rockwell painted The Four Freedoms as an homage to President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Four Freedoms speech, which FDR delivered as the United States increasingly faced involvement in the Second World War. In the speech, Roosevelt sought to rally the public around core values he believed motivated Americans. These values, these freedoms, as FDR characterized them, offered an integrative core for American democracy that could transcend partisan rancor and unite citizens around the things they loved about their country and hoped to preserve in an age of rising fascism and totalitarianism.

Does that Rockwellian respect for (and even glorification of) the civic process still apply today? Could we see that painting without asking ourselves whether the man in the picture is on our side or not? Could we rally Americans around the values of the four freedoms today? Are we more or less likely to be enthusiastic about the freedoms of speech and religion today? More important, are young people more or less likely to be enthusiastic about those things? And how many would look at the Rockwell painting and find its most comment-worthy feature to be the predominance of white people? Have we, in our attempts to bring about greater equality and representation, somehow perversely managed to increase tribalism? I suggest only the salience of these questions, not answers to them.

Competing Forces

Augustine said you can know a people by what they love. If they are just, they will love Jesus Christ, but regardless, they will love something, and by that we will know them. What do Americans love? My students give non-reassuring answers: sex, shopping, money. We could come up with more charitable responses, but whatever it is that we love, is it enough? Can we love each other? That's part of what I am getting at with my concern about a lack of integrating factors. Is part of what we have lost the Rockwellian picture of the importance of real people in a room listening to each other speak about a life they share?

When I ask myself the question of whether democracy has had its day, particularly in the United States, I find myself comparing the forces of deception, manipulation, and dissension to those of civic virtue and integration. Will the demagogues, radicals, tribalists, and manipulative "conditioners," as Lewis called them, weaken the fundamental structures so much that they fail? Will we appreciate true philosophers more than sophists? Have we become so good at deconstruction that there is little remaining of the foundations? Or have we cultivated and stewarded enough reserves of democratic virtue and friendship to sustain our lives together?

What will be left if the center of the old consensus doesn't hold? Do our constant efforts at focus-grouping and expertly crafting messages create brittle materials for political construction? Do we disdain the philosophic quest of Plato and the spiritual quest of Christianity in favor of Machiavelli's worst strategies for winning, and then congratulate ourselves on our techniques?

These questions lead me to reflect on the crisis of Hong Kong's democratic protest against China. Generally speaking, I think we have believed that as a nation becomes wealthier and more technologically advanced, it will also become more democratic. As people rise above subsistence and gain access to education, they become increasingly empowered to stand up for themselves and to petition the government for representation. In other words, they would have a natural tendency to move from being subjects to becoming citizens.

The Chinese regime challenges that assumption. Over thirty years ago, we saw democratic feelings emerge and be brutally put down in Tiananmen Square. Though we took some joy and inspiration in the image of the unknown Chinese man standing courageously in the path of tanks, we also had to ruefully acknowledge that the tanks and the oligarchs won the day.

Hong Kong has recently risen as another test case. The Chinese mainland issued an ordinance that would permit extradition from the city to the mainland. That proposition is frightening to Hong Kong's citizens because extradition outside one's political community presents a classic opportunity for intimidation, the unpredictability of justice, and a lack of transparency in the administration of laws. Trials far from home were one of the outrages that propelled the demand for the Magna Carta. Protests have gone on in Hong Kong for many months, yet the Chinese Communist Party appears to be willing to double down.

There are some interesting things about the Hong Kong protests. First, there were American flags in evidence, implying that the Hong Kongers locate support for freedom in the propositional country of 1776 (again, not the slavery country of 1619). Second, Christian songs, such as "Sing Hallelujah to the Lord," were sung as hymns of the protest. Third, music from Les Misérables competed with anthems of state. Fourth, some Chinese blamed the "liberal studies" class Hong Kong students take as a source of discontent.

Taken together, we see the materials of something like a Christian humanism undergirding Hong Kongers' desire for freedom and genuine citizenship. But in order to be effective, the symbols must signify something. There has to be a there there. The verdict is still out in Hong Kong. The verdict is probably still out for us, as well.

Some Final Questions

One thing haunts me in vague fashion as I think through these matters. Mahatma Gandhi was able to prevail against the British colonial masters with his campaign of nonviolence inspired by Jesus Christ. So, too, was Martin Luther King, Jr., able to win out against formal structures of racial segregation in the U.S. In both cases, the prophets, so to speak, were able to appeal to the oppressors as men with some kind of Christian conscience. What would have been the outcome had the oppressors been steeped in different beliefs and ideals? Context matters. What has our context been? What is our context becoming?

And maybe that takes us to a nice concluding point for our inquiry into the question of whether democracy has had its day. I began with a description of how democracy went from being thought of as a bad thing to becoming the standard (even if only as the least bad of all options). The Bible and Christianity (maybe scriptural Protestantism most of all) played significant parts in accomplishing the transformation. The ancient thinkers separated good forms of government from bad ones by pointing to the difference between those obliged to follow constitutions versus those that operated in essentially arbitrary ways. I noted the genius of the American founders in countering the shifting designs and passions of factions by adopting the Ciceronian model and dividing power in the constitutional order, but I also observed that their design has increasingly given way to a more typical majoritarianism.

Structure counts for a lot, but so does the body politic itself. And so we ask ourselves Platonic and Lewisian questions about the souls of citizens. Are our heads and hearts rightly ordered and functioning as they ought? Is there some integrating force in our democracy that holds us together in a kind of mutual affection and appreciation for virtue? If so, is it strong enough to prevail against the acids of division and distinctly unconstructive partisanship? As we look at the kinds of things that seem to motivate the hopeful democrats of Hong Kong, we might wonder whether we can still recognize those things in ourselves.

What are the integrative forces to which I refer? I'm thinking about religious faith, for one thing. A variety of changes has led us to the point where faith is held less in common among Americans than it used to be. A broad-based Christian belief was once significantly more prominent than it seems to be today. The end of the Cold War has also left us more divided, for lack of a common enemy and a common fear. We also have to consider the impact of the revolution in sex and marriage and the related fallout from the introduction of the modern welfare state. Families have diverged substantially from the traditional nuclear norm. Technology has contributed to the growing power of narrower and narrower factions, such that one can find reinforcement for almost any constellation of beliefs and behavior. What still brings us together?

Without digging deeply into the debate between Sohrab Ahmari and David French over the proper stance of Christians in the political and cultural wars that rage around us, I suggest that the reason why that debate has become so compelling to many of us is that the foundations of the old procedural republic seem to be crumbling. It's one thing to have a good set of rules, but you also have to have citizens who share enough good will and affection to continue agreeing to play by those rules. If we see everything as a battle between the two titanic forces of purity and corruption, then rules may appear as nothing more than the refuge of those willing to sell out.

That's why we are beginning to hear it put forward in some quarters that even free speech—an unquestioned value in my youth—is actually just an artifact of "white privilege." But upholding free speech is one of the ways we actually protect a democracy's ability to do the job we need it to do, which is to provide a check on power. Do we have the trust to forego the temptations of hot political will in favor of obeying the limitations of cool constitutionalism? Constitutions are difficult to modify for a reason.

Has democracy had its day? I don't see any end to human beings voting—not in the West at least. Not in consumer-dominated societies. But the problem I do foresee is that we will increasingly reject constitutional democracy in favor of either mob rule of the kind feared by ancient thinkers or a regime of administrative law led by C. S. Lewis-style "conditioners," in which all the real governing is done by "experts" and voting largely amounts to stagecraft. The form will persist, but the substance will be another matter.

Hunter Baker , J.D., Ph.D., is the dean of arts and sciences at Union University, a fellow of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, and an affiliate scholar of the Acton Institute.

subscription options

Order

Print/Online Subscription

Get six issues (one year) of Touchstone PLUS full online access including pdf downloads for only $39.95. That's only $3.34 per month!

Order

Online Only

Subscription

Get a one-year full-access subscription to the Touchstone online archives for only $19.95. That's only $1.66 per month!

bulk subscriptions

Order Touchstone subscriptions in bulk and save $10 per sub! Each subscription includes 6 issues of Touchstone plus full online access to touchstonemag.com—including archives, videos, and pdf downloads of recent issues for only $29.95 each! Great for churches or study groups.

Transactions will be processed on a secure server.

more on America from the online archives

more from the online archives

35.4—Jul/Aug 2022

The Death Rattle of a Tradition

Contemporary Catholic Thinking on the Question of War by Andrew Latham

calling all readers

Please Donate

"There are magazines worth reading but few worth saving . . . Touchstone is just such a magazine."

—Alice von Hildebrand

"Here we do not concede one square millimeter of territory to falsehood, folly, contemporary sentimentality, or fashion. We speak the truth, and let God be our judge. . . . Touchstone is the one committedly Christian conservative journal."

—Anthony Esolen, Touchstone senior editor